Karen Loomis suggested at her talk at Scoil na gCláirseach last week, that we try taking stereo pairs of photographs in the museums in Dublin on Tuesday. I am only just now starting to go through my pictures and see what I have. Here’s a first trial – grab your red/cyan goggles and see what you think!

Category: Uncategorised

Fíor mo mholadh ar Mhac Dhomhnaill – medieval bardic poetry performance

This is the final set at the Ceòl Rígh Innse Gall concert in the museum at Armadale, Isle of Skye, last month: medieval Gaelic ‘bardic’ poetry, sung with accompaniment played on the replica of the medieval Scottish ‘Queen Mary’ harp.

Fíor mo mholadh ar Mhac Dhomnaill

Cur la gceanglaim cur gach comhlainn

True my praising of MacDonald, hero I am tied to, hero of every fight

Croidhe leómhain láimh nár tugadh

Guaire Gaoidheal aoinfhear Uladh

Lion’s heart, hand that did not reproach, Guaire of the Gael, sole champion of Ulster

Aoinfhear Uladh táth na bpobal

Rosg le rugadh cosg na cgogadh

Champion of Ulster, welder of people, eye which caused the ceasing of warfare

Grian na nGaoidheal gnúis í Cholla

Fa bhruach Banna luath a longa

Sun of the Gael, face of the sons of Coll, around the Bann his galleys were swift

Cuiléan confaidh choisgeas foghla

Croide connla bile Banbha

Furious hound, stopping raiders, steadfast heart, tree of Ireland

Tír ‘na teannail deirg ‘na dheaghaidh

A bheart bunaidh teacht go Teamhair

The land is a blazing beacon behind, his ancestral duty to go to Tara

Measgadh Midhe onchú Íle

Fréimh na féile tréan gach tíre

The confuser of Meath, the wolf of Islay, the root of bounty, the defender of each land

Níor éar aoinfhear no dáimh doiligh

Craobh fhial oinigh ó fhiadh n-Oiligh

Refusing no-one, no pleading poets, generous honourable branch from the land of Oileach

Níor fhás uime acht ríoghna is ríogha

Fuighle fíora fíor mo mholadh

No-one raised with him but kings and queens. True these judgements; true my praising

Poet: anonymous MacMhuirich c.1500

Singer: Gillebrìde MacMillan

harpist: Simon Chadwick

After the music finishes we hear Godfrey, Lord MacDonald, speaking with the ‘vote of thanks’.

Something a bit different

Two-bell ringing

Sometimes at St Salvators tower we are short-handed, and we have been gradually working our way though The Chris Higgins Guide To Three-Bell Ringing (ed. Ian Chandler, Kirby Manor Press 2003). I have been enjoying the elegant simplicity of the music as well as the physical challenge of placing and striking the bell well.

Today, being the first day of semester at the University of St Andrews, and also the morning of the clocks changing, there were only two of us. There are two two-bell methods in the book, and we tried them both – Cambridge being a little more pleasant, with more intellectual challenge as well as less physical. But then I fancied something different and so invented on the spot some stedman-style methods which I see now loking though my notes also share some charateristics of the ultimate 3-bell method, Shipping Forecast.

The idea is to lie, point and lie. You can lie for 2 or 3 blows, and you can arrange the blocks of 2 and 3 lying adjacent or alternating.

x=xx=x=xx= or x=xx==x=xx== or x=xx==x==xx=

We rang the three and the five, the University’s two medieval bells, whose minor 3rd interval was to me the characteristic sound of the tower before the augmentation in 2010.

I wonder if it would be possible to make a connection with the binary music of Robert ap Huw and the other late medieval / early modern Welsh secular instrumentalists? Was this most fundamental art of change ringing used before changes on higher numbers were developed?

In medieval Welsh notation we might write for the three methods above

00100.11011 and 001000.110111 and 001000.111011

Finally we discussed a little what to call this type of ringing. The book unimaginatively describes these methods using just the word “two”. We can do better than that. The convention for odd numbers of bells is to count the number of simultaneous changes possible, so on 3 is singles, 5 is doubles, 7 is triples, and so on. On even numbers, Latin descriptors are used: 4 is minimus, 6 is minor, 8 is major, &c. I proposed “micromus” but I don’t know if that is too silly!

Medieval Scottish sword

I have a new sword, which I acquired secondhand. It was made in Czechoslovakia by Nielo – there seems to be a number of very good bladesmith craftsmen in Eastern Europe. It is nicely made and seems a quality piece of work. Though it is over 10 years since I last did any historical fencing this seems a very good sword.

I have been looking for a long time for a sword of this type. The drooping quillons with broad ends are the really distinctive thing here and these differentiate this “Scottish style”, and they are what develop to give the classic “claymore” or “twa-handit sword” of the 15th to 17th century.

The West Highland grave slabs, such as the ones at Keills, show similar swords but with viking style lobed pommels. Was there a real difference between the designs of the West and the East in the 14th and 15th century? Or were the late medieval West coast stone carvers deliberately showing an archaic design? I don’t think there are any extant examples of the lobed-pommel type whereas there are a number of this wheel-pommel type surviving. Here is an excellent example in Kelvingrove museum, Glasgow.

I could have done with this in 2011, when I ran my Battle of Harlaw music workshops. We spent part of one of the sessions looking at the effigy of Gilbert de Greenlaw, and discussing his arms and armour. He is carrying exactly this kind of sword – again in an East coast context. We also looked at some of the West highland effigies.

The sword does not have a scabbard, so making one is my next project. I need to look at more of the effigies and stone slabs to get a better idea of how they work.

Eskimo violin / Inuit fiddle / Tautirut

I have finally acquired a copy of archive recording of tautirut playing from 1958 held by the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec.

Tautirut is the Inuit word for the bowed harp or box zither played in the area around northern Quebec and southern Baffin Island. It has strong connections to other bowed-harp traditions in Scandinavia and further afield. For more on the wider bowed-harp and bowed-lyre traditions I have made a bowed-harp web page.

The collector Asen Balikci was visiting Povungnituk in Quebec in 1958, and he seems to have commissioned the people there to make a couple of “reconstructions” of the tautirut. I assume the “reconstructions” were necessary because the tradition was moribund there by that date.

Cariola, then 38 years old, played tunes on the newly made instruments. Balikci recorded her playing and took the instruments and the tape recordings back to the Museum.

The instruments are similar to each other; each has three sinew strings. The bow is strung with a willow root. They have only one bridge, so the strings must be fingered where they come off the soundboard, not into the air as on the Icelandic Fiðla and earlier Tautirut.

Here are the catalogue entries for the two instruments:

IV-B-648 made by Peterussie

IV-B-649 made by Krenoourak

Krenoourak’s instrument looks better; it is longer (though still not as long and slender in shape as the late 19th and early 20th century instruments), and it includes two little bits of wood which are now separate but which I presume are connected to tuning the instrument. These things have no tuning pegs; the strings are just attached to the ends, or in Krenoourak’s case, to leather straps attached to the end. Peterussie’s instrument is extremely short and fat, but it does have an ivory nut at each end where the strings pass over the ends.

Here is the museum catalogue entry for the sound recording:

Control no. IV-B-46T

Cariola’s playing is very interesting, fast and obviously improvised. She uses different tunings; in the earlier tracks she has the instrument tuned with the drone a 4th below the melody note; in later tracks the drone is dropped to an octave below the melody note. I am particularly interested in the track that sounds like a trumpet fanfare, with the melody on 1st, 3rd, half-sharp 4th and 5th of the scale, with the octave bass drone. Her intonation drifts; sometimes it is clean and deliberate, while at other times it is rather wayward.

Her instrument is tuned higher than Sarah Airo’s (see my earlier post) but the general style of playing and the sound is similar. Cariola seems to use the drone more sparingly, touching it at the same time as playing the stressed melody notes, whereas Sarah is more often alternating between the melody and drone strings so the drone becomes a rythmic part of the tune. I wonder about this being a woman’s music, and about the style – it does seem to be connected to other bowed-harp styles from Scandinavia. And the players were 200 miles apart – though perhaps that is not very far in Northern Quebec.

Now to listen and learn some of the motifs and playing techniques!

Ceòl mór or pibroch for the clarsach

Right from the very beginning of my harp studies I was fascinated by the idea of ceòl mór on the harp. I started studying the first tunes (Fair Molly, the Butterfly and Burns March) from November or December 1999, and I think it was just a couple of months later that I found a cassette tape copy of Ann Heymann’s Queen of Harps in an Oxford Celtic/New Age shop. That recording, apart from eternally smelling of patchouli, of course has Ann’s 30 minute performance of her version of the pibroch, Lament for the Tree of Strings.

I think I was taken by the intricate repetitiveness of the music, like a journey through a landscape, or perhaps more pertinently like the folded geometric patterns in medieval manuscripts such as the Book of Kells. I was also interested in the abstract nature of the tunes, which are very different from the more “tuney” tunes more commonly found in traditional music nowadays.

I made a page on my old website about ceol mor, where I searched for inspiration and information.

The first ceòl mór tune I played on the harp was Cumh Easbig Earraghaal, the lament for the Bishop of Argyll, the manuscript source for which is reproduced in Alison Kinnaird’s and Keith Sanger’s book Tree of Strings. I think it took me a long time to get to grips with this tune but in some ways it made perfect sense to me – this is exactly what ancient harp music is meant to sound like, the contrasts between the different variations, and the opportunities for exploring different timbres and idioms as the variations progress. I continued to play and develop this tune and included it on my first CD, Clàrsach na Bànrighe, in 2008.

Ceòl mór is a genre of music that is best known nowadays as pipe music, played on the great highland bagpipe, where it is known as pibroch or pìobaireachd. I say “best known” though in fact you rarely hear pipers playing this type of music; it is rarely included in concert programmes, living instead in a rarefied world of piping competitions. I worked for a while with historical piper Barnaby Brown, on projects including promoting both piping and harping on the internet and developing online teaching resources. His unusual insight into the historical pibroch traditions gave me some useful understandings of the nature of this music and how it might live nowadays. Traditionally it belongs to the pipes and the fiddle and the old Gaelic harp with metal wire strings, and I feel each of the three instruments brings something different and unique to the music. None of them is “imitating” the other, each wholly owns the music and expresses some true deep spiritual essence of it in its own way.

I have continued to work on Gaelic harp ceòl mór; my latest CD Tarbh is entirely pibroch tunes (and I wonder if it is the first CD ever to be 100% harp ceòl mór). It is hard to market; it is serious music but it does fall between stools – too serious for traditional music followers, too traditional for classical and early music people. Pipers who play pibroch seem intruiged by it. When I perform concerts and include a big 10 minute ceòl mór tune, I am always nervous as to how the audience will react – will they be bored and restless? But afterwards I find people come up and say, that was the best piece of the whole concert!

Ceòl mór is such a huge world for me, I think I could spend the rest of my life just studying and playing this repertory. There is something truly meditative about the power of the music. More than one person has said how it is reminiscent of Indian Raga music, and I think it is the way that it selects just two or three notes and then cycles meditatively around them. There are points in some of the pibroch where a new tone appears and hits you with the force of emotion and power – I find it fascinating that such emotional intensity can be built up from such apparently simple material. Perhaps it has that intensity because of its deliberate, austere simplicity.

Edinburgh Harp Festival

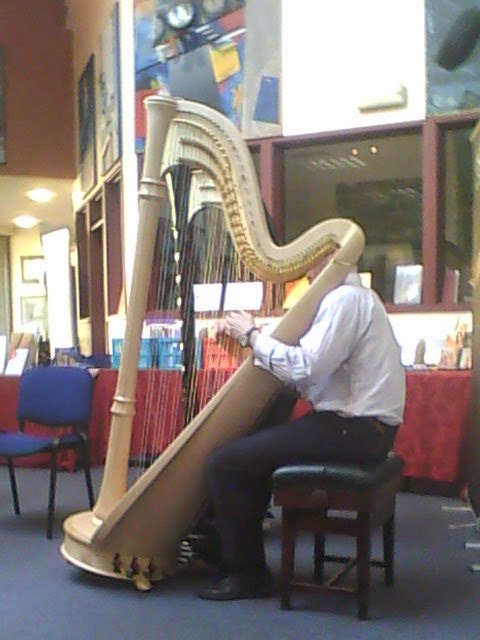

This is a portrait of harpmaker Tim Hampson, with the replica Erard single-action pedal harp that he made – one of the best harps at the harp festival each year in my opinion.

This is a photo (taken by Karen Loomis) of me playing a very interesting harp that was at the Telynau Vining stand. It is a Welsh triple harp made by the Llandudno maker Hennesy Hughes (I think) in the late 19th century. I was very keen to play this harp as it is set up for left-orientation player (right hand bass, left hand treble), with the bass singling out to the right side. It was really a delight to try this harp – I usually have great troubles playing triple harps as they are almost always set up for right hand treble, left hand bass playing.

More info about this harp from Camac.

Mendelssohn on Welsh music

Ein Harfenist sitzt auf dem Flur jedes Wirthshauses von Ruf und spielt in einem fort sogenannte Volksmelodieen, d. h. infames, gemeines, falsches Zeug, zu gleicher Zeit dudelt eben ein Leierkasten auch melodieen ab … von kreischenden Nasenstimmen gegröhlt, begleitet von tölpelhaften Stümperfingern…

Letter from Mendelssohn’s tour of Scotland and Wales, 25 August 1829, cited in Gelbart, The Invention of “Folk Music” and “Art Music”, Cambridge 2007 p248. A nice snapshot of harp and crwth playing together.

An English view of Scottish music

“Music they have, but not the harmony of the sphears, but loud terrene noises, like the bellowing of beasts; the loud bagpipe is their chief delight, stringed instruments are too soft to penetrate the organs of their ears, that are only pleased with sounds of substance”

Thomas Kirke, A Modern Account of Scotland by an English Gentleman, 1679