Paul Smith was a traditional Irish harper in the late 19th and early 20th century. I think he was the very last professional Irish harper in the inherited tradition. He died in poverty, ignored and marginalised. This post is to begin gathering information about him.

At the moment there are huge gaps in our knowledge of Paul Smith’s life and music. Most of the references to him come from the end of his life, but they are very complete since he lived into the 20th century and so we have quite a few official records of him.

His age is given in two different official records, but they don’t match. In the census in March 1901 his age is given as 79, but on his death record in 1904 his age is given as 80. So at the moment we can’t say more than that he was likely born some time between about 1822 and 1824. We know that he was blind. We are told that he was born in the City of Dublin, and we are told that his father was a manservant, also called Paul Smith. I haven’t tracked down the father at all.

Education

As always in the 19th century, a blind child of a poor family would have very limited opportunities in life. The Irish Harp Society school was still running in Belfast in the 1830s, offering a free vocational education to become a professional traditional harper, and so I think it is possible that Paul Smith may have been sent by his parents to Belfast to study the Irish harp under Valentine Rennie and subsequently under Alexander Jackson, initially in Cromac Street and then for the last year or so in Talbot Street. But we have virtually no records of the students attending the school in the 1830s so we cannot know.

If Paul Smith learned the harp in Belfast, he may have been enrolled in the mid 1830s, aged perhaps about 12 to 14. He may have continued as a student right through to early 1840 – we know there were two pupils still there from August 1839 until early 1840.

This is all pure speculation, and Paul Smith may have learned privately from someone else. The only thing that makes me suspect the Belfast school as a possibility is firstly his age, and secondly that he got his harp in 1840 which would fit with him being discharged from his studies in that year.

A harp like this was expensive; perhaps around half a year’s wage for a manservant like Paul Smith’s father. We can be pretty sure that the harp was presented to Paul Smith in 1840 in recognition of him having attained a professional standard of musicianship on the traditional Irish harp, either by the Irish Harp Society in Belfast or by a private patron. I discuss Paul Smith’s harp in a lot more detail below.

Anyway, from 1840, at the age of about sixteen to eighteen years, Paul Smith had his harp, and was out on his own as a professional harper, playing the traditional wire-strung Irish harp to make his living.

Professional career

We have only one mention of Paul Smith working as a professional harper. I assume that is because he made his living working under the radar of the newspapers and other published sources. He may have played every evening in a tavern; he may have played for private events for wealthy patrons. He may even have had a regular noble patron who employed him at the house for private events. It is possible that we may in future find references to this kind of work in someone’s private correspondence or papers. But at the moment I have nothing at all.

The Harp Festival in 1879

In 1879, the Swedish classical pedal-harpist Adolf Sjödén was in Ireland, and he organised a series of three “harp festival” concerts in Dublin at the beginning of May 1879. Sjödén was entirely in the classical-music world, and his concert programmes drew together the best of Irish classical musicians. I get the impression that Sjödén and his collaborators were intending to kind of kick-start a national revival of the harp in Ireland, based squarely on international classical music norms.

Sjödén’s work and the Festival has been studied by Helen Davies and Lia Lonnert, but their research has not yet been published. When it is, this will give a lot more background about Sjödén and his classical music collaborators at the Festival.

I have over 50 newspaper clippings about the festival, mostly advertisements and previews along with a few reviews of the performances. A typical advert from just before the first performance reads like this:

IRISH HARP REVIVAL

Irish Times, Monday 5th May 1879 p2

FESTIVAL,

IN THE ROTUNDO,

TUESDAY 6th, THURSDAY 8th, and SATURDAY 10th of MAY,

AT EIGHT O’CLOCK IN THE EVENING.

______

HERR ADOLF SJODEN

BEGS TO ANNOUNCE A

Classified Selection of Ancient Irish Music,

to be performed by

A CHOIR OF PEDAL HARPS,

LED BY HIS GRAND FRENCH (ERARD) HARP.

________

TRIO OF ANCIENT IRISH WIRE-STRUNG HARPS.

________

Welsh Airs on the Ancient Welsh Harp with Three Rows of Strings.

________

Herr Sjoden will be assisted by the following Eminent Artistes:

Miss Bessie Craig |Sir Robert Stewart

Miss Johann Ward | Professor Glover

(Pupil of the Royal Irish| Mr Levey

Academy of Music) |Herr Elsner

Mrs Mackay | Herr Lauer

Mrs Power O’Donoghue | Mr Lloyd

Mr Oldham | Mr Lumley

Mr Little | And Several Distin-

Mr Albert M‘Guckin | guished Amateurs

________

Conductors – Signor Caracciolo and Mr Richard Harvey.

________

The Irish Music will be comparatively Illustrated by Scottish, Welsh, English, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish and other National Airs.

________

Mr. LEVEY will play with Herr SJODEN

A Selection from his Celebrated

Collection of

“THE DANCE MUSIC OF IRELAND”

________

One of the last surviving of the Celebrated Blind Irish Harpers will play on the Ancient Irish Harp strung with wire.

Celebrated Irish Pipers will also perform in the interval on the Union Pipes.

________

PROGRAMME FOR TUESDAY, the 6th MAY.

Part 1. Miscellaneous.

1 – Grand Trio for Harp, Violin, and Violoncello, Oberthur.

Herr Laner, Herr Elemer, and Herr Sjoden.

2 – Song. “Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep” Knight.

Mr Albert M‘Guckin

3 – Aria. “Batti Batti” (from Don Giovanni) Mozart.

Miss Bessie Craig.

4 – a. “La Danse des Sylphes” Godefroid

b. Hymn from the 6th Century Liszt

c. Turkish Parade March Parish Alvars

For the Harp

5 – Song “Guinevere” Sullivan

Miss Johanna Ward.

6 – “Ave Maria” Meditation on Seb.

Bach’s Prelude Gounod

For Violin, Harmonium and Harp

Mr Levey, Sir Robert Stewart, and

Herr Sjoden

PART II

Irish Music with comparative illustrations

1 – Irish Airs played on the Ancient Irish Wire Strung Harp, by an Irish Harper.

2 – a Ancient Irish Air

b “The Tailor’s Son”

Miss Bessie Craig.

Words written expressly to this air by

Sir Samuel Ferguson

3 – “Echoes of Erin”

For Harp Solo . Herr Sjoden

4 – Trio upon Irish Airs for Three Irish Harps

5 – Selection from Mr Levey’s Celebrated

Collection.

“The Dance Music of Ireland”

For Violin and Harp.

Mr Lover and Herr Sjoden.

6 – Fantasia upon Irish Airs for Harp and Pianoforte

by Mrs Mackay

Mrs Mackay and Professor Glover

7 – Irish Airs for a Choir of Pedal Harps

8 – “No, not more Welcome”

Miss Johanna Ward

9 – Welsh Airs on the Ancient Welsh Harp

Strung with three rows of strings.

10 – a Carolan’s Concerto

b “The Irish Cry”

c “The Little Red Fox”

Numbered Seats, 4s; Reserved Seats, 3s: Balcony, 2s; Area, 1s. Subscription tickets, admitting for the three evenings, 10s, 7s 6d and 5s. At the principal Music sellers.

These huge and detailed adverts ran every day in multiple newspapers, with changes to the details as the programmes were adjusted from one concert to the next. But from our point of view we can instantly recognise the vast majority of this as not at all part of our world. This is all full-on Classical re-imagining of national music, with choirs of pedal harps, pianos, and classical singers. Even when we get the Welsh Triple harp and the trio of Irish (wire-strung) harps in the second half, I am sure that these are being played in classical style by Sjödén and his classical pedal harp colleagues, as part of the comparative display of different harps. A review does not find these acts convincing:

…it included a performance on three Irish harps strung with wire, but the effect was not very grand or impressive, and the audience, and even Herr Sjoden himself, appeared relieved when they were put aside…”

Dublin Daily Express, Wed 7 May 1879 p5

But enough about the classical musicians. We are trying to find out about the traditional harpists.

There are only two traditional musicians mentioned in this entire listing; and they are not named in this advert. One is the “Irish pipers” who will play in the interval, and the other is “One of the last surviving of the Celebrated Blind Irish Harpers will play on the Ancient Irish Harp strung with wire” who plays immediately after the interval, at the start of the second half. The same review of the first (Tuesday) concert quoted above, describes the two traditional musicians, and names the piper:

During the interval which followed – or rather, which was supposed to follow – a novelty was introduced in the shape of a blind Irish piper (Mr. O’Flaherty) who performed on the Union pipes the well-known piece “The Foxchase.” He was encored principally by the back benches, and he was followed by another novelty – a blind Irish harpist, who performed a selection of Irish airs on the ancient Irish wire strung harp. The effect coming after the full rich-toned instrument used by Herr Sjoden was not very brilliant, however clever the performer may have been.

Dublin Daily Express, Wed 7 May 1879 p5

This is very interesting, in that the reviewer is obviously not interested in traditional music; his cutting comment about the “back benches” shows that O’Flaherty’s piping was appreciated mostly by the poorer lower class attendees and not by the wealthier concert-goers. And his comment about the traditional harp music is revealing – that the player was “clever” i.e. using interesting and complex playing techniques, but that the voice of the traditional wire-strung Irish harp was weaker or less impressive than Sjödén’s top-of-the-range Erard “Gothic” pedal harp played with the flashiest Classical harp techniques.

We don’t learn who the harper is, until an advert for the second (Thursday) concert. The whole programme has been changed, with additions, but the bit that concerns us is the description of the interval:

…In the interval Mr O’Flaherty the Irish Piper will play the celebrated piece

Irish Times, Thur 8 May 1879 p2

“M‘DONNEL’S LAMENTATION,”

And Mr Smith the Irish Harper will play on the

Wire Strung Harp…

Mr Smith! Here he is at last.

The advert in the Dublin Daily Express of that same day does not name the harper. A review of the Thursday concert in the Dublin Daily Express, Fri 9th May 1879 p4 does not even mention the traditional performers in the interval; the Irish Times review (9 May p5) praises O’Flaherty but does not mention our harper. The reviewer for Freeman’s Journal gets a bit confused, but is obviously unimpressed with the traditional musicians and didn’t think they were very important compared to the classical musicians:

…”M‘Donnell’s Lamentation” was played on the irish Hornpipes by Mr. O’Flagherty. A blind piper and a blind harper played a rather long exercise on a wire strung harp…

Freeman’s Journal (Fri 9 May 1879 p5)

Many of the adverts for the third and final concert on the Saturday either don’t mention the traditional musicians, or mention them but don’t name them. We have two mentions of the harper by name.

…In the interval Mr O’Flaherty will play (by special desire) the celebrated piece the

Irish Times, Sat 10 May 1879 p2

“FOX CHASE.”

Mr Smith, a blind Irish harper, will perform on the Ancient Irish Harp Strung with Wire…

…In the interval Mr O’Flaherty will play the celebrated piece, “The Fox Chase”

Freeman’s Journal, Sat 10 May 1879 p4

Mr Smith on wire Harp…

We also have a couple of reviews after the third and final concert, and while they both spend most of their time discussing and praising the classical performances in the main parts of the concert, they both mention our traditional boys in the interval:

…Mr O’Flaherty, a blind Irish piper, played “The Foxchase” in a manner eminently suggestive, the wild and inharmonious strains contrasting beautifully with the tuneful utterances of more cultured and less neglected instruments. A blind Irish harper, Mr. Smith, then took up the tale with a fantasia of national airs on a so-called ancient Irish harp, his performance being equally creditable…

Freeman’s Journal, Mon 12 May 1879 p7

…Mr O’Flaherty (Dr. Lyons’s Irish piper) played, by request, the “Fox Hunt,” and was boistrously applauded, and as on the former occasions imperatively required to play other Irish pieces. Mr. Smith, the blind Irish harper, performed with plaintive expression some national melodies on the wire string harp…

Irish Times, Tue 13 May 1879 p6

You will notice that we are nowhere told Mr Smith’s first name; but I have no doubt at all that this is our man Paul Smith who was playing on those three evenings.

This entire episode is fascinating, and there are many layers of cultural significance that could be usefully unpicked. The thing that strikes me most of all is how marginalised Paul Smith was, and yet he was there. I find the description of him being “one of the last” to be a common trope; we can check my timeline to see that there really were only a handful of traditional harpers left by 1879. In Belfast there was Pat Murney, Sam Patrick, and the amateur George Jackson. There may have been a few amateurs in Drogheda from Father Burke’s Society, who had been taught by Hugh Fraser in the 1840s, but the only one I can be sure of was Peter Dowdall. Roger Begley was in England. Hugh O’Hagan had been working in Dublin in the early 1870s but by 1879 he had gone back to Dundalk. Probably the only traditional harper in Dublin was Paul Smith.

You can see a powerful dynamic emerging in Sjödén’s programming, whereby the classical pedal harp was being framed as the Irish National Instrument. This was not new; Egan had been marketing pedal harps like this from early in the 19th century. But we see it really taking shape in this festival, with the sound of the pedal harp, and the classical playing technique and arranging style of Irish tunes, are normalised and promoted. We see the young Owen Lloyd, a virtuoso pedal harp student of Sjödén, appearing on stage in the main body of the programme, in what was I think his first ever public appearance (on the Thursday concert, Lloyd played Oberthur’s “Transcription of a Bohemian National Air for the harp”, while on Saturday Lloyd played “Harp solo: Irish Planxties”). Perhaps we can see the inclusion of Paul Smith alongside the piper O’Flaherty, as “novelties” in the interval, as a way for the classical harpists to appropriate the old tradition into their world, to pay token respect to it while at the same time showing it up as an inferior predecessor to their competent internationalist classical world. Certainly that was the impression that reviewers and presumably concert-goers took away.

Even the way Paul Smith was given the first proper slot in the second half of Tuesday’s concert, but was demoted to the interval for the second and third concerts, speaks volumes about how he was seen and received.

Smith’s traditional harp playing techniques cannot have been framed favourably by being put into the interval amongst all this classical music. O’Flaherty at least stood alone as something unique; the description of his “wild and inharmonious strains contrasting beautifully with the tuneful utterances of more cultured and less neglected instruments” (i.e. classical pedal harps and piano and violin) gives us a sense of how Paul Smith’s traditional wire-strung Irish harp would have been viewed. Yet at least O’Flaherty had a uniqueness factor; there was no classical equivalent to the Irish pipes as far as the concert-goers and reviewers were concerned, and so the pipes could be seen to have value as an exotic novelty that could carve its own space alongside the “more cultured and less neglected instruments” of classical music. Paul Smith would be seen as merely playing an inferior and obsolete version of “the harp”, in an inferior style to the classical harpists, and so could be marginalised, ignored and ultimately written off.

Later professional career

After 1879, Paul Smith must have continued working as a professional musician playing the traditional Irish wire-strung harp, though as before we have no information about what he was doing. He may have been busking on the streets, like Begley in England (though if he was you would think he would be better known to people in Dublin), or he may have had a regular slot at a pub or coffee shop. Either way I am not finding references to him anywhere. He was listed as a “musician” on his wedding certificate in 1891 and so he was presumably still working at that stage. He was in his late 60s by then.

Missing out on gigs

I am starting to see a pattern emerging, of the types of work that the traditional harpers would normally have got, being taken instead by classical pedal harpists marketing themselves as “Irish”. Actually I don’t know if this was a more general thing or a one-man campaign to steal work from the traditional harpers, waged by the ambitious and brilliant young pedal harpist Owen Lloyd.

I found the piper O’Flaherty playing at the Viceregal Lodge (now Áras an Uachtaráin in Phoenix Park) in May 1886. We know that Patrick Byrne had played at the Viceregal Lodge in the 1840s and 1850s and so we might have expected O’Flaherty to be working there now with Paul Smith, reprising their earlier partnership from the interval of Sjödén’s festival.

Most of the reports mention “an Irish piper and an Irish harper, who played some of the old airs… the piper was Mr John O’Flaherty, a pupil of the celebrated McHammond…” (Cork Constitution, Mon 24 May 1886) and some give a lot of information about O’Flaherty and his tune lists.

However I found one report (Irish Times Mon 24 May 1886) which names the Irish harper as Owen Lloyd. So already then we see the traditional musician O’Flaherty, with his traditional uillean pipes, alongside the “Irish harper” Lloyd playing classical arrangements of Irish tunes on his Erard double-action pedal harp. I think this is part of the legacy of Sjödén’s festival.

Meanwhile Paul Smith was living in a grotty tenement down on the quays, trying to eke a meagre living playing his traditional wire-strung Irish harp which he had learned in the inherited tradition.

Getting married

On 18th January 1891, when he was in his late 60s, Paul Smith married Anne Jane Mann who was in her mid 50s. Neither had married before; they were neighbours who lived in the same tenement building at 30, City Quay in Dublin.

The wedding was at St Mark’s Church, Dublin. The witnesses were Anne’s sister and brother-in-law, Elizabeth and George Ellis.

I think this is very sweet, that the two of them got together at that age. I presume they moved in together into one of the tenement apartments on City Quay. We will discuss the different addresses they lived at later on.

The marriage also gave Paul Smith an instant family living in City Quay, in the form of his sister-in-law Elizabeth Ellis and her daughter Margaret Ellis, who became Paul Smith’s niece.

The first Feis Ceoil, 1897

In the 1890s, the Gaelic Revival was starting to gather momentum. Conradh na Gaeilge was founded in 1893, to promote the revival of the Irish language, and the other arts were also being rapidly developed in a self-conscious movement of nation-building.

Planning for the first Feis Ceoil began in 1896, because of a perceived neglect of Irish music and musicians. The main organiser was Dr. Annie Patterson who was an organist and classical composer. The entire Gaelic Revival scene was a very urban and middle-class movement, and there were heated discussions through the first decade or so about what Irish music should be like, with many people considering that it would be a mistake to valourise peasant music, and that Irish music should be a national flavour of international classical music. Reg Hall discusses this in his 1994 PhD thesis, Irish music and dance in London, 1890-1970: a socio-cultural history, e.g. p86-87. He mentions the classical harp being used in the Gaelic revival on p87 but he does not realise that there were still traditional harpers around at that point.

This preview article was written in October 1896, seven months before the actual event:

Those interested in the proposed Irish Musical Festival, to be held in Dublin next May, will be glad to learn that the Feis Committee are busily at work getting ready their plan of action, and arranging various competitions. These latter may be said to cover the whole ground of musical achievement so far as that ground has been broken in Ireland. They are divided into choral, vocal, instrumental, and composition competitions. The choral competitions will include two for choral societies of not less than thirty and sixteen members respectively, for which close on £100 is offered in prizes. Then there are competitions for adult and school choirs, for unaccompanied quartets of both mixed and equal voices, and for solo singing. It is not contemplated to have competitions for full orchestras on the first occasion of the holding of the Feis, as such orchestral bodies can hardly be said to exist in Ireland. There will, however, be competitions for wind band, fife and drum band, string quartet, modern double action harp, violin, ’cello, pianoforte, harmonium, and solo wood and brass wind instruments. Interesting from an archaeological point of view will be the competition for a solo performance on the ancient Irish wire-strung harp, for which, in addition to the 1st prize of £5, there will be a golden trophy for the best performer, and another competition for ancient Irish pipes will be attractive, provided there are any pipers to compete. In composition, a valuable money prize will be offered for the best cantata for solo voices, orchestra and chorus, not to exceed 40 minutes in performance, the words to be by an Irish author, or the subject to be Irish. Prizes are also offered for the best part song, anthem, motet, string quartet, Irish song, violin and pianoforte duet, pianoforte solo on Irish subject, orchestral overture, and arrangement of Irish airs for band and voices. The full particulars of all these competitions will be published shortly, but these are the chief details, which, through the kindness of a member of the committee I am enabled to give you in advance.

Weekly Irish Times, Sat 17 Oct 1896 p4

As with Sjödén’s festival seventeen years before, we see the traditional Irish pipes and the traditional wire-strung Irish harp given a place, but that place being carefully constrained and kept separate from the “real” music. At Sjödén’s festival they were in the interval; here at the Feis they are of “archaeological interest” (i.e. not really of musical interest).

I am also very interested that there is a lavish prize for the traditional harp, but the writer comments that the pipe competition “will be attractive, provided there are any pipers to compete”. It sounds like they thought they would more likely find traditional harpers than traditional pipers.

The harp historian Robert Bruce Armstrong saw these notices, and he describes in his book:

In 1897, when the first Feis Ceoil was about to take place, the writer, understanding that a prize had been offered for the best performance upon the wire-strung harp, requested that a seat from which he could see the fingering of the performers should be reserved. The reply was that, after diligent inquiry, the Committee were forced to come to the conclusion that there was not a performer living.

R. B. Armstrong, The Irish and Highland Harps (1904) p52

The competition was held in the Molesworth Hall on Saturday 22nd May 1897. A full review appeared in the Monday newspaper:

THE FEIS CEOIL

Freeman’s Journal, Mon 24 May 1897 p5

_____

THE CLOSING DAY.

The centre of attraction for patrons of the Feis on Saturday was at Ballsbridge, where the competition between brass and reed bands, and also for solo instruments composing them, was held. The archæological competitions in the Molesworth Hall were conducted in the absence of the public.

ARCHÆOLOGICAL COMPETITIONS

Competitions of an archæological interest were fixed for Saturday. These consisted of playing on the Irish harp and the Irish bagpipes, and of the production and playing or singing of an Irish air hitherto unpublished.

IS THE IRISH HARP EXTINCT?

Mr W J Simpson, Belfast, presented a gold trophy in the form of an Irish harp for the best performance on an Irish wire-strung harp of any size. The Feis Committee offered three prizes, one of £5, the second of £3, and the third of £1 for the same. There were no entries.

Mr Simpson has given his trophy to the committee for the best competitor at the Feis. the award will be announced when the adjudicators make their report.

EIGHT UNPUBLISHED IRISH MELODIES.

THE PIPES AND THE PHONOGRAPH.

Mr P J M‘Call, T C, presented a prize of £3 for the discovery and vocal or instrumental performance of an ancient melody hitherto unpublished. The judges in this and the Irish harp competition were Dr Sinclair Boyd, Dr Culwick and Mr Nally. There were eight entries. The judges required the competitors to sing or play into a phonograph, which was done on Saturday in the Molesworth Hall. There will be an enquiry during the next few weeks as to whether any of the melodies so recorded have been published, and the prize will be declared to the best melody or collection of melodies found to fulfil the condition as to non-publication, coupled with merit in the playing or singing. Meantime a provisional award was as in the order of merit of the pieces and their performance. There were eight entries, consisting of seven pipers and one vocalist. The singer was Mr Myles Conicher, a Dublin man, who sang in the Irish song competition, and won one of the prizes, and the pipers were Turlough MacSweeny, Gweedore, Co Donegal; John Flanagan, Dublin City; Richard Lewis Meally, Boyle, Co Roscommon; Thomas Rowsom, Dublin; Dennis Delaney (the blind piper), Ballinasloe; Robert Thompson, Cork; and John Cash, Summerhill, Co Wicklow.

… [article continues with details of their tunes, and then a long report on the wind band competitions]

So what was going on? Paul Smith was living on City Quay, fifteen minutes walk from Molesworth Street. He had his big traditional wire-strung Irish harp, he was a professional harper in the inherited tradition. In 1897 he would have been aged in his mid 70s, perhaps on the point of retirement, but all he had to do was turn up and play a tune to get the first prize of £5 and the gold trophy. The cash prize would be something like a thousand pounds today and would have been very useful to someone on the breadline living in a one room tenement apartment.

I think the most likely explanation is that Paul Smith and his family living in poverty in the tenements on the Quays, did not know about the middle-class Feis Ceoil. And I also think that no-one on the Feis Committee or their middle and upper class contacts and associates would know about a poverty stricken traditional musician living in a tenement on the Quays.

I think this is yet another example of the deeply socially stratified social worlds of 19th century Ireland.

Yet the pipers came from as far away as Gaoth Dobhair, and they played the pipes into the phonograph, and made wax cylinder recordings of their tunes. There is a fair amount of scholarship about these early piping competitions, for example Barry O’Neill in The Seán Reid Society Journal vol 1 March 1999. It is not clear to me if the actual wax cylinders from 1897 survive; there are often references to them such as by Cathal Póirtéir at UCD but I can never find concrete details, catalogue entries, or digitised versions. I think the original cylinders may be held at the National Folklore Collection (NFC), University College Dublin.

Imagine if one of the committee had gone to Paul Smith’s wee tenement room on City Quay, and brought him over to Molesworth Hall to play into the phonograph machine, and then sent him home with £5 and a gold trophy.

But they didn’t.

Naturally, Owen Lloyd played his Erard double-action pedal harp at the Feis Concert, alongside a piper, to illustrate “ancient and middle period Irish music” (The Musical Times, 1 Jun 1897 p392)

Paul Smith was probably the only professional harper in the old tradition still alive in 1897. But there were also a couple of amateurs still alive in 1897, men who had learned to play on the traditional wire-strung Irish harp in the inherited tradition, from teachers who had learned in a lineage back to the 18th century harpers. (see my timeline). Peter Dowdall was in Drogheda; he had learned from Hugh Fraser in the 1840s, who learned from Edward McBride and Valentine Rennie in the 1820s, who had both learned from Arthur O’Neil around 1810, who had learned from Owen Keenan in the 1740s. Dowdall had learned to play the traditional wire-strung Irish harp, but he never worked as a professional harper as far as I know; he worked as a clerk. And there was George Jackson in Belfast, who had learned probably in the 1850s from Patrick Murney, who learned in the 1830s from Valentine Rennie and so on. Jackson could play the traditional harp well, according to someone who heard him, but he wasn’t a professional harper. He worked as a clockmaker.

There is also a tantalising mention of another person, in a review of the following year’s Feis:

There is a blind girl in the South of Ireland who plays on the old wire-stringed Irish harp – probably the only instance of its survival in the country.

Freeman’s Journal, Thur 5 May 1898 p6

I don’t know if this is true; if it is, I don’t know who she might have been. She is on my timeline as a stub. Even if she did exist, she would not have been the only one left.

Retirement?

In the 1901 census, Paul Smith is listed as “no occupation” so perhaps he had retired or stopped working by that stage, and was being supported by his wife Anne who was listed as a dressmaker.

Discovered by a Gaelic revivalist

Séamus Ó Casaide was a Gaelic revivalist and piping enthusiast in Dublin. He joined Conradh na Gaeilge around 1899, and from 1900 he was involved with Éamonn Ceannt in the newly formed Cumann na bPíobairí (Dublin Piper’s Club).

The Piper’s Club organised a concert which was to be held in December 1902. The minutes of their meetings contain discussion about the plans for the concert. I have not seen the original minutes but they are summarised and paraphrased in an article: Breandán Breathnach, ‘The First Piper’s Club in Dublin’, An Piobaire 4, March 1970, p33-36.

The minutes tell us about the kind of music that was to be in the concert. As well as a number of pipers, some of whom had to be brought in from far away and boarded in Dublin, they were to get a “four hand reel” from a branch of Conradh na Gaeilge, Miss Bergin to sing to her own harp accompaniment, a recitation, a solo performance on the cello, and a street fiddler. There was to be a piano hired for the event.

The relevant note from the minutes is paraphrased by Breathnach:

Mr. Cassidy undertook to see about a certain veteran harper whose whereabouts he had discovered. Failing him, Owen Lloyd was to be asked to play free

Breathnach 1970 p35

Seán Donnelly originally told me about this reference, and he also mentioned that in Séamus Ó Casaide’s papers in the National Library there is a reference to the harper being Paul Smith, and living in City Quay, but neither Séan nor I have been able to track down the exact reference to this note.

Breathnach also prints a review of the concert from the Freemans Journal.

PIPERS’ CLUB CONCERT

Freeman’s Journal, 15 Dec 1902, quoted in Breathnach 1970 p36.

The Concert of the Pipers Club, held in the large Concert Hall of the Rotunda on Saturday Evening was very largely attended, and a really excellent programme was submitted. The first item was a well-rendered selection on the pipes and fiddle by Messrs. Kent, Doran and O’Toole … The selections on the harp by Mr. Owen Lloyd were of course given in a very finished manner…

So what happened? Did Séamus Ó Casaide ever get in touch with Paul Smith? Did he go down to the tenements on City Quay and knock on the door and ask Paul to play? Did Paul refuse, because he was too old, or too ill, or what? Paul Smith would have been almost 80 years old by this date.

Or did Séamus Ó Casaide not get around to it? Was it just easier to get the popular, well-known classical harp virtuoso Owen Lloyd to play instead? Lloyd was well known on the Gaelic Revival scene; he had become an Irish language activist, styling himself “Eoġan Laoide”; he had acquired a wire-strung “Egan” Irish harp in late 1902, which he was announced to play at the “great Gaelic concert” in the Rotunda on Monday 24th November 1902 (Freeman’s Journal Thur 20 Nov 1902 p5). That announcement says “this will be the first time since the great Belfast meeting of harpers in 1792 that a large Irish wire-strung harp has been heard in public” which is blatantly untrue. And so the erasure of the inherited tradition and its replacement with Owen Lloyd’s classical playing powered ahead.

The 1901 census included a question about language ability in English and Irish. Paul Smith is listed as “English only”. This is what we would expect for an old man who had been born, raised, and lived his life in Dublin. The Irish language was in steep decline throughout the 19th century, especially in the East of Ireland, and was only beginning its big renaissance as part of the middle-class Gaelic revival from the 1890s. For more on this see Aidan Doyle, A History of the Irish Language (2015) p.177-205; see also the language map on p166.

Anyway, the Irish language revival was one more way in which the young middle-class virtuoso classical pedal harpist and Irish language activist Eoġan Laoide could get one up on the traditional harpers who had learned to play the wire-strung Irish harp in the inherited tradition in the mid 19th century.

Death

Paul Smith died on 14th August 1904, in the tenements at 29, City Quay which I think was where he and Anne lived. His death record says he was a musician, aged 80 years. The death was reported by his niece Margaret, who lived at no.30 (I think 29 and 30 were the same block of tenement apartments), and who was present when he died.

Selling the harp

After Paul Smith died, his widow Anne continued to live in the tenements at no.29 City Quay, and the harp must have stood in the corner. However, a couple of years later, Anne got in touch with the National Museum, to see if they would buy the harp from her.

There is a file of correspondence between the Museum and Anne Smith, in the National Museum of Ireland Archives (Science and Art File of Correspondence, File No 327, A&I/06).

It is not clear to me from the file how the interaction started, how Anne got in touch with the Museum. The earliest item in the file seems to be a re-used scrap of paper. On one side of it is a note, not addressed to anyone but presumably to Anne Smith, asking her for a 1 shilling donation and 2 “useful garments” for the St Patrick’s Guild. The note is signed E & H Rothwell, 23 Brookfield Terrace. I managed to find Helena and Elizabeth Rothwell in the 1901 census; they were wealthy sisters who lived with two servants. Helena died on 18 Nov 1906, leaving an estate worth over £3,000 to her sister Elizabeth. There must be some kind of back story here about the wealthy sisters organising a charitable guild (which I have not managed to track down) and tapping destitute parishoners for donations.

Anyway, on the back of the note from the Rothwell sisters, Anne Smith has written a pencil note, saying simply “any hope of my husband’s harp being bought by the Museum?” This note must have been passed informally to someone in the Museum, perhaps after a face-to-face conversation, because it ended up in the file of correspondence. But it is most mysterious.

We are on a proper footing with the next item, which is a page from a Science and Art Institutions minute book, and contains a series of short handwritten notes back and forth between two members of the Museum staff, Mr Buckley and Mr White. It reads like a thread of text messages on a phone screen.

Mr White,

I went to see the Harp at Mrs Smith’s 29, City Quay, about which you spoke to me a few days ago. It is an interesting old instrument of the forties in the last century. The owner said she thought it was worth £20. it is somewhat similar to, though of later date than, one already in the Collection, but if it were offered for about £10 , should recommend its purchase.

[JJ] Buckley

10th march 1906Mr Buckley

If we already have a similar Harp I don’t think (unless you strongly recommend) we should offer for this one

[White]

12/3/6Mr. White,

If we could get this for £10 I should strongly recommend its purchase JJBMiss [Luke] write offer on the [form] which says that [similar] [articles] are in the [museum] [??] & offer £10 [???] [???] [???] [???][???] [White]

National Museum of Ireland Archives (Science and Art File of Correspondence, File No 327, A&I/06)

One of the things that fascinates me about this discussion is that neither man has any interest in the provenance of the object. I think that nowadays, the Museum would try to document as much as possible about the working life of the object; they would have gone to interview Anne about her late husband’s professional career as a traditional harper, and they would have asked her if there was anything else that went with the harp: papers, ephemera, perhaps Paul Smith’s certificate from harp School, perhaps the tuning key and cover, perhaps information about his performances… but they did not. They were only concerned to add the harp to the collections for as low a price as possible.

The next item in the file is obviously Miss Luke’s “offer”, written on the “form”. It is a fascinating document purely from a Museum Studies point of view. It is a printed letter, with blank spaces left for the Museum staff to fill out the specific details. I imagine that the Museum must have had constant offers of objects, at inflated prices, and that this printed letter was designed to automate the process of counter-offering a low price.

The printed letter says

Your Offer of a ________ to the Museum at a price of £_______ has been under consideration and I am directed to inform you that though the _______________ of some interest, the price asked seems very high.

National Museum of Ireland Archives (Science and Art File of Correspondence, File No 327, A&I/06)

If you are willing to take £____________ for the _____________ purchase will be recommended

The printed letter has been completed by hand, filling in the blanks. The date is 13th March 1906, the object is “Harp”, the price being refused is £20, and the price being offered is £10. The letter has Mr White’s illegible signature at the bottom.

The next item in the file is a very eloquent and moving letter that Anne Smith has written in reply to the form.

March 17th 1906

National Museum of Ireland Archives (Science and Art File of Correspondence, File No 327, A&I/06)

No. 29 City Quay

To H. B. White [Eqr]

Sir

In Reply to your Letter of March 13th No. 61/962/06 Re The Harp

I Beg Leave to Say that I will accept your offer of £10 – 0 – 0 for it altho I consider the Price Very Low My Reason for Saying this is that it is an Old Heirloom Being Specially Built for my late Husband Paul Smith about 75 years ago But I Know It will be well Taken Care in the museum & also I know that it will not Go Into Strange Hands Thanking you in anticipation

Your Obedient Servant

Ann Jane Smith

29 City Quay

Dublin

She has exaggerated the age of the harp, since it has the date 1840 written on it, so it would have been only 66 years old at this point.

At the bottom is an endorsement from White:

Mr Buckley note

National Museum of Ireland Archives (Science and Art File of Correspondence, File No 327, A&I/06)

Store Keeper Please send for the Harp

[White]

16/III/6

There is also a carbon copy of a typewritten letter from H. B. White to Anne Smith:

16th March 1906

National Museum of Ireland Archives (Science and Art File of Correspondence, File No 327, A&I/06)

Madam,

I beg to inform you that your letter has been received accepting our offer of £10 for the harp. I have instructed the Storekeeper here, Mr. Montgomery, to call for it and bring it here, and we shall be happy to forward you an order in payment for the amount in a day or two.

Yours faithfully,

Chief Clerk and Second Officer,

Institutions of Science and Art.

There is also a series of registration forms which state that the harp was received at the Museum and passed to Buckley on 19th March 1906.

The accession register lists the harp as 1906/64 and gives a physical description of the decoration, including the date 1840, and transcribing the inscriptions, and says the height is 5 feet and there are 38 strings.

And that’s it, the harp was in the Museum, Anne Smith got her £10, and Paul Smith was forgotten about.

Anne Smith died on 28th August 1908, at her niece Margaret’s house, at 8 Petersons Lane which is just back from City Quay. The death was reported that same day by Margaret. Anne is listed as a widow, age 70, a dressmaker.

Later references to the harp

Robert Bruce Armstrong saw the harp in the Museum, and he measured its string lengths and gauges. His pencil notes are preserved with his own copy of his 1904 book in the Royal Irish Academy (RIA Library SR 23 G 35). The notes are written on headed notepaper of the Royal Hibernian Hotel, Dublin, and Armstrong has headed his notes “Harp in Dublin Museum”. He has transcribed the inscription including Paul Smith’s name. I don’t know the date of Armstrong’s visit to the Museum, but he doesn’t seem to have known about Anne Smith. He never visited her to ask her about her husband’s harp or music. He didn’t know who Paul Smith was. He never realised when he was working on his great 1904 book, and trying to find out as much as possible about the playing techniques and music of the traditional wire strung harp, that he could have gone to Dublin and walked down to City Quay and chapped on the door of no.30 and asked Paul Smith to show him how it all worked.

A photograph of Paul Smith’s harp was published in Rosalyn Rensch’s book The Harp (1969) plate 28c, p112, and again in Harps and Harpists (2017 revised edition) p119. But the caption there does not identify it or name Paul Smith; they do not even seem to realise that it is a traditional wire-strung Irish harp. The caption reads “Large non-pedal harp made by Francis Hewson in 1840…”

You can also see Paul Smith’s harp in a surprise cameo appearance on TV in 1984. This is a RTÉ feature on the then newly restored Casino at Marino, and Paul Smith’s harp is there as a decorative furnishing.

Studying Paul Smith’s harp

I think I first saw Paul Smith’s harp about 14 years ago, on the 2009 Scoil na gCláirseach field trip to the Museum. The inscription on his harp is the earliest documentary record of Paul Smith that I have seen so far, and it was the first time I came across his name. The harp has two inscriptions, one saying “Made by Francis Hewson for Paul Smith”, and the other giving the date 1840. For many years I used to wonder “who is Paul Smith?”, but I didn’t start to work it out until I started my long 19th century project just under one year ago.

After I started my Long 19th Century Project, and I realised about Mr Smith playing at Sjödén’s festival, and I found Paul Smith in the records, living through into the early 20th century, I realised that he was a very important tradition-bearer, and I realised that his harp was important as well. I was especially interested in it as the working instrument of a tradition-bearer which had gone from his hands, (albeit with a year and a half sitting in his widow’s room), direct to the National Museum. To me this suggested it likely retained its original working stringing and setup.

I went to the Museum Store with Brenda Malloy, and together we inspected and measured Paul Smith’s harp.

Paul Smith’s harp is of the normal 19th century design of traditional wire-strung Irish harp. I think this design originates with the harps designed and made by John Egan for the Irish Harp Society in Belfast in the early 1820s. Egan’s harps have 37 strings. Paul Smith’s harp was made after Egan had died, and it was made by Egan’s nephew Francis Hewson. Paul Smith’s harp has 38 strings, but otherwise the design is pretty close to Egan’s original design. There are subtle differences of construction and profiling.

There are two other traditional wire-strung harps of this model made by Francis Hewson, that I know of. One belonged to Hugh O’Hagan, and is now in Dundalk county museum (1988.1104). I wrote a report on it as part of my write-up of Hugh O’Hagan. It is in much worse condition than Paul Smith’s. The other was associated with (maybe owned by) Owen Lloyd probably in the nineteen-teens or twenties, and is now in the National Museum of Ireland collections (NMI DF:1951.2). I don’t know who it may originally have been made for; it doesn’t have the second inscription naming the harper. It is dated 1849 on the soundboard.

Paul Smith’s harp has inscriptions on it which are very useful in giving its full provenance. On the soundboard front at the bass end is a duplicated pair of inscriptions, the same each side of the centre strip. First there is a kind of pseudo heraldic crest, done in gilding: a pair of wolf-dogs flanking a shield which has a heraldic Irish harp on it. The background to the shield is deep blue, I think it is Lapis Lazuli. The shield has pikes or spears behind it, and a five-pointed Irish crown as its crest. There are green painted shamrocks wreathing around the gilded edge of the shield. There is a gilded scroll shown underneath, with black lettering reading “GENTLE WHEN STROKED / FIERCE / WHEN PROVOKED”. Then underneath this there is black lettering: “FRANCIS, HEWSON. / HARP-MAKER / NEPHEW & SUCCESSOR / To The LATE / JOHN, EGAN / 19 SOUTH KING ST / Dublin / A.D. 1840″

On the right side of the neck-pillar joint, i.e. the display side for a traditional harp played left hand high and right hand low, is gilded lettering which reads “MADE By FRANCIS, HEWSON. / For PAUL, SMITH.”

As usual for 19th century traditional wire-strung Irish harps, Paul Smith’s harp has taper tuning pins, and bridge pins, but does not have any kind of semitone mechanism – that was a classical feature that was only used by harpists re-inventing the Irish harp (lever harp) from a classical background. The inherited tradition of playing the wire-strung Irish harp never required any kind of classical key-changing system.

The strings on Paul Smith’s harp are all brass wire, and most of them are present even if not complete. Brenda Malloy and I measured the diameters and sounding lengths of every string.

| String number | dia (mm) ±0.1mm | length (mm) ±5mm | notes |

| 1 | 0.4 | 55 | |

| 2 | 0.4 | 67 | |

| 3 | 0.4 | 75 | |

| 4 | 0.4 | 85 | |

| 5 | 0.4 | 90 | |

| 6 | 0.4 | 102 | |

| 7 | 0.4 | 113 | |

| 8 | 128 | completely missing | |

| 9 | 0.7 | 136 | |

| 10 | 0.7 | 148 | |

| 11 | 0.7 | 158 | |

| 12 | 0.7 | 170 | |

| 13 | 0.7 | 186 | |

| 14 | 0.7 | 200 | |

| 15 | 0.8 | 220 | |

| 16 | 0.7 | 245 | |

| 17 | 0.7 | 275 | |

| 18 | 0.8 | 295 | |

| 19 | 0.8 | 318 | |

| 20 | 0.9 | 350 | |

| 21 | 0.9 | 380 | |

| 22 | 0.9 | 415 | |

| 23 | 0.9 | 450 | |

| 24 | 0.9 | 490 | |

| 25 | 0.9 | 510 | |

| 26 | 0.9 | 565 | |

| 27 | 0.9 | 622 | |

| 28 | 0.9 | 691 | |

| 29 | 0.9 | 765 | |

| 30 | 1.1 | 842 | |

| 31 | 1.1 | 940 | |

| 32 | 1.1 | 1010 | |

| 33 | 1.1 | 1070 | |

| 34 | 1.1 | 1125 | |

| 35 | 1.1 | 1180 | |

| 36 | 1.2 | 1230 | |

| 37 | 1.1 | 1290 | |

| 38 | 1.1 | 1340 |

I have discussed the traditional stringing regimes and my understanding of them on my stringcharts page, though I still have a lot to learn. It is possible that Paul Smith used a memorised string chart specifying the number of strings of each gauge number, but during the course of his life the gauge number systems for wire got thicker. Or that he misremembered his rules, and had no colleagues left to ask for corrections. I don’t know.

Anyway we can analyse this string chart assuming it is what Paul Smith used towards the end of his life.

The string lengths are similar all the way down to John Egan’s 1820s design, though a bit shorter; it is hard to know how much this is due to distortion due to damage to the soundbox. I would presume that Paul Smith would have required the unisons at na comhluighe g and the bass gap at tead leagaidh e/f, because these seem to me to be essential for the traditional playing techniques. But at present I don’t think there is any actual evidence either way, I am just assuming he played using the traditional playing techniques, and that he therefore would have required these features in his tuning and setup.

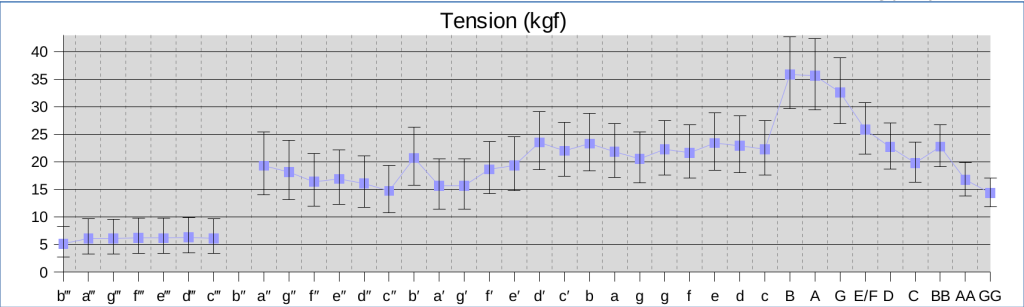

Here is the result of my analysis, showing how the tension changes over the range of the harp.

The first thing that strikes me is that this harp has thicker and heavier strings than I would expect, or than I see on other traditional wire-strung Irish harps.

The main thing I see is that Paul Smith has used much thicker wire for the treble (2nd and 3rd octaves down) than I would expect. There is a big jump in tension between a″ and c‴, two octaves above middle c′. I would expect this big jump to be at na comhluighe g. The other thing is that I don’t see a real system or logic to where Paul Smith changes gauge. He has 9 strings of the thickest gauge (about 1.1mm). Then at about B/c he changes to the next size down (about 0.9mm); he has 10 of this size, before changing down again just above middle c′, to the next size down again (about 0.7mm). He has 11 or 12 of this size, and then at between a″ and c‴ he changes down to a much smaller size of treble wire (about 0.4mm). There are about 7 or 8 of this thinnest size right to the top of the harp.

You can also see that this chart puts about 700kg of force on the harp. This is about 40% more that I have on my chart for the 37 string Egan design. I would be a bit scared to put this much tension on the harp. I would worry that it might break. In fact I would expect it to start to distort and break in the same way that Paul Smith’s harp has, with the soundboard pulling up, the pillar base breaking, and the back starting to bend.

I note that Paul Smith’s harp has fractured across at the bottom of the soundboard, and in fact all three of the Hewson traditional wire-strung harps I know of have broken here. It is possible that this is a design flaw of Hewson’s harps, or it is possible that all three were strung too heavily. Paul Smith’s harp also has some distortion in the shell of the soundbox caused by string tension.

I think there may have been subtle pressure on the harpers to beef up the stringing by the late 19th century; when John Egan designed this model of harp in the 1820s, its voice and power was compared favourably with the sound of contemporary pedal harps (the Erard Grecian model). But by the second half of the 19th century, classical pedal harps had got a lot bigger, stronger, more heavily strung and more powerful (with the introduction of the Gothic model). It is possible that the kind of unfavourable comparison of the traditional wire-strung Irish harp against the much more powerful and heavier-strung Gothic pedal harp that we saw in the reviews of the Sjödén festival in 1879, may have been the kind of thing that could encourage the traditional harpers to experiment with heavier stringing, ultimately breaking their harps in the quest for a bigger sound. It’s my informal understanding that many early 19th century classical harps were broken in the late 19th and early 20th century by players fitting heavier string sets to them. In the historical harp and restoration movements, there are often cautions about restringing antique harps, to use historically-appropriate string-sets, so as not to over-stress the frame.

The only way to really find out is to commission a good harp-maker to make an accurate replica, trying to use the same kind of wood and making all the parts the same thickness, and then stringing it according to the chart and bringing it up to tension, and then seeing if it breaks, or if it works excellently. If you would like to sponsor the cost of this experiment, please get in touch and we can get to work! It should cost between £6k and £10k and we might or might not have a useable harp at the end of the experiment.

I also looked inside the soundbox to see Paul Smith’s toggle windings. The toggles are fairly rough-cut wooden dowels, and the strings are wound around them in a very simple knot, very similar to the minimum knot possible that I discovered by experiment, with a single turn around the toggle and a long tail end which sticks out.

Brenda and I also measured the square tuning pin drives, to see what size of tuning key Paul Smith would have needed. The drives are tapered (which is normal and very important for traditional wire-strung Irish harp). The drives measure 5.7mm across the flats at the shoulder between the round shaft and the square drive; they reduce to 5mm across the flats at the very end. This is significantly more slender than the sizes I measured on one of Egan’s harps which were 6.8mm at the widest and 5.8mm across the tip. Paul Smith would need a smaller key to tune his harp. I think the harpers who got the Egan harps in the 1820s would have been able to use the same keys to tune them, as they would have needed to tune the 18th century harps. I need to measure more tuning pin drives to build a better picture of the traditional norms through the 19th century.

Aside from my suggestion above of the crazy experiment of making an accurate replica and stringing it to see if it breaks, I think that Paul Smith’s harp would be an excellent model for a new working traditional harp. A new accurate copy could be strung more conservatively with a thinner midrange regime, something like my John Egan chart which works very well. It would be an excellent harp to use for the traditional Irish harp repertory. It would be very ergonomic and should speak well when played using the traditional playing techniques and idiom (e.g. following Sylvia Crawford’s reconstruction of the system). If the painted and gilded decoration was also copied, the new harp would also be a stunning art object. The provenance connection of the original back to Paul Smith, a traditional Irish harper in the 20th century, would give the new copy a great cultural significance.

Life on City Quay

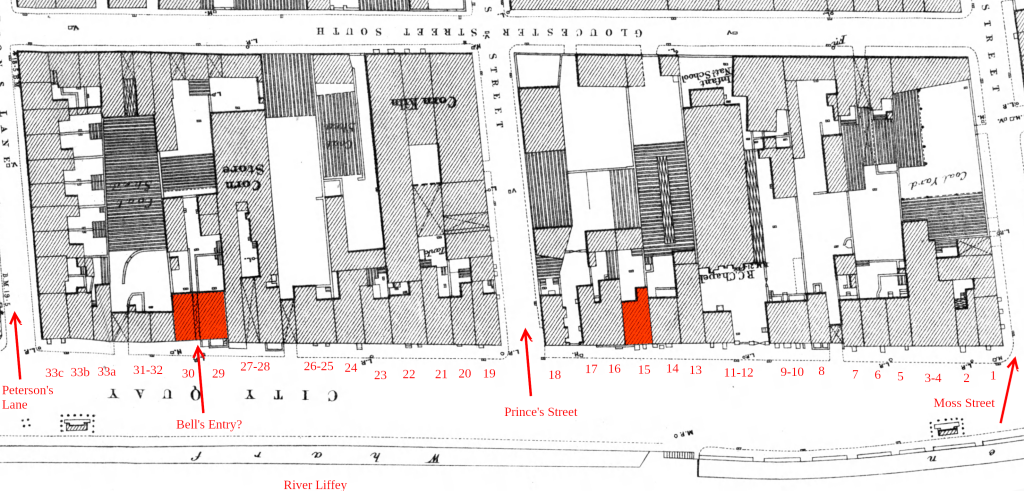

Paul Smith and his wife Anne lived on City Quay, Dublin, from the time of their marriage through to their deaths.

Basically we have three references to Paul Smith’s address. On his marriage certificate in 1891, both he and his wife were living at 30 City Quay. In the 1901 census, they are both at 15 City Quay. On Paul Smith’s death certificate in 1904 he is listed as dying at 29 City Quay. After he died, his wife Anne continued to live at 29 City Quay.

The 1901 census lists everyone’s names and addresses on the night of Sunday 31st March 1901. The household return lists Paul Smith, head of family, and Anne Jane Smith his wife. Anne can “read + write” but Paul is listed as “neither” (he is also listed as “blind”). He is listed with “no occupation” and she is listed as “Dress Maker” so it looks like he had basically stopped working as a musician, and she was supporting them both. Both are listed with place of birth as “City of Dublin”.

Perhaps most intriguingly, Paul Smith and his wife Anne are listed in the 1901 census as “church of England”. I don’t yet understand the significance of this. From 1800, with the acts of Union, the Church of England and the Church of Ireland were formally combined into the United Church of England and Ireland. This Union came to an end in 1869 when the Church of Ireland was disestablished and separated from the Church of England. Paul Smith would have been about 45 years old at this point. When he and Anne married, their wedding was in the Church of Ireland parish church of St Mark’s. Perhaps there was some liturgical or political reason why some people might declare their allegiance to the Church of England instead of to the Church of Ireland at that point. I don’t know.

Paul Smith’s death was reported by his niece Margaret, who was present at his death; it says on his death record under her name 29 City Quay, but 30 has been heavily over-written over the 29. She was in a tenement apartment in No.30 in the 1901 census, along with her husband Christopher Smyth and her daughter from a previous marriage, Lizzie Wiley. They are all listed as Roman Catholic. Margaret’s father was George Ellis, who had married Ann’s sister. I think it must be a co-incidence that Margaret’s new husband was called Smyth, as I don’t see a direct family connection between Christopher Smyth and Paul Smith. We can also track the niece Margaret’s addresses over the years. She was born on 13th April 1877 at 29 City Quay. When she married John Wiley on 14 Nov 1897 her address was given as 30 City Quay. He drank himself to death a year and a half later. When Margaret married again, to Christopher Smyth on 10 Feb 1901, her address is again given as 30 City Quay, and they are at no.30 in the 1901 census. But she had moved off the quay, round the corner to Peterson’s Lane by the time Anne died in 1908.

Anne’s sister and brother-in-law and brother John are all listed as Church of Ireland, but niece Margaret is listed as Roman Catholic. Perhaps she had to convert to marry her two sequential Catholic husbands.

I get the impression that the people living in the tenements on City Quay formed a close knit community, and that they would flit fairly often from one apartment to another.

We can collate the Thoms Directory entries for 1889, 1892 and 1912 with the 1901 census to see who was at what address on City Quay. We can see that the houses were not re-numbered over this time period. You can look at my spreadsheet which contains summary entries from all these sources lined up together.

You can look at the 1889 Ordnance Survey five feet to one mile plan of the houses on City Quay online at UCD Digital Library. I have rotated the map (South to the top) and I have labelled the map with my best guess as to which house corresponds to which number in the directories and census. I have marked what I think is likely nos. 15, 29 and 30 on the map. I am not 100% certain that I have got all of the numbers correct.

If I have got it right, we can see that nos. 29 and 30 are really one building, with a passage running through the middle to the three houses behind on Bell’s Entry. Both 29 and 30 are tenement houses, with a family living in each room. No.15 is also a tenement house like that.

We can compare my annotations on the 1889 map, with this aerial photograph from 1933. At the far right of this crop (below) is Moss Street. You can count the house numbers from the right, with no.1 on the corner of Moss Street. The Catholic Church, set well back from the street, is no.11-12; no.15 may be the low dark building directly above the stern of the ship. No.18 is the little tall thin house on the corner of Prince’s Street. Then on the left corner of Prince’s Street is no.19, and on the far left is no.33 on the corner of Peterson’s Lane (now where Elizabeth O’Farrell park and Peterson’s Court is). I am guessing that numbers 30 and 29 may be the two tall thin buildings directly above the motor-car on the road. These are demolished already in a 1949 aerial photograph.

The National Library of Ireland has a superb photograph of a ship moored on City Quay which seems to date from around 1900 (certainly between 1889 and 1915). Below I have cropped the photo tight to show the buildings on City Quay. I think the entrance to the chapel is on the extreme right edge of this image, so the tall pale building with three windows on each floor would be nos. 13-14, and then no.15 would perhaps be the dark obscured building behind the lamp post. But it looks like there may be a partly demolished building there as well. Nos.29-30 would be in the next block further down the street, perhaps around where the next lamp-post is, but I can’t distinguish the individual buildings that far down the street.

It seems to me that the people who lived on City Quay were mostly dock labourers, working on the dockside with the ships which came and went full of cargo. It seems that City Quay was a place where barrels of Guinness would be unloaded from the barges which came down from St James’s Gate, to be re-loaded onto sea-going ships for export. But plenty of other cargo would have been loaded and unloaded on the quayside. We see on the maps and censuses that some of the premises along City Quay had big yards and sheds out the back, as coal stores or grain stores. Other premises were shops or businesses connected to the docks such as rope and sail makers. The crowded tenement houses would have been occupied by the men who worked on the docks and their families.

Jim Nelson has written an amazing memoir of his childhood at his grandparents house, no.15 City Quay, the same house where Paul and Anne Smith were at the time of the 1901 census. His grandparents had taken over the whole house after the last tenants died in the 1920s. Jim Nelson describes the family, the community, and the physicality of the old building, with the floors sloping alarmingly due to subsidence in the dock rebuildings. He says the house was finally demolished in the 1980s. It is worth reading his long piece in full, as an atmospheric pen-picture of life on City Quay.

There has been a huge amount of redevelopment of the City Quay area in the second half of the 20th century. Very few buildings from Paul Smith’s time there are still standing. There is a very interesting RTÉ TV report from 1967 which interviews some of the dock labourers living there, about how they were to be cleared out to the suburbs so that the residential streets could be demolished and replaced by new industrial areas.

Now, a giant glass edifice stands on the site of no.15, overshadowing the church beside it.

The site of nos.29-30 is now a row of modern Housing Executive style houses, set back from the road. You can look at them, and explore City Quay on Street view.

Many thanks to the National Museum of Ireland, Jennifer Goff and Sarah Nolan at the Arts and Industry division and Christina Tse at the archive, for facilitating my visits to see Paul Smith’s harp and Anne Smith’s correspondence.

Thanks for a great read Simon!

Fabulous — thank you for this in-depth, and much needed, research!

Another fascinating article – thank you!

Absolutely brilliant, Simon. Thank you for your attention to detail and so many strands to the story. I’ve seen this harp a few times in the NMI storage, and you really have brought the provenance to life.

It really is a wonderful thing. To know so little and yet so much of this man. I love Anne’s exchange with the museum and seeing his name on the harp. I love that you’ve done justice to all these wonderful people — the way that you’ve brought them to life for us. It’s just great!

So, it’s sounding pretty certain — Dare I ask it? — Is Paul Smith truly the very last of the old traditional players?

Paul Smith was the last professional traditional harper as far as I can see so far.

But George Jackson was still alive in Belfast until 1909. He was an amateur harper, he worked as a clockmaker, but we are told he was “a fair player of the Harp”. A year ago, I wrote about how he fitted brass strings to a harp in 1908. I think George Jackson was probably the very very last of the old traditional players.

Theres’s a very interesting review of the first Feis Cheoil, in the Weekly Mail, 22 May 1897 p2, online at the National Library of Wales. This review of the different days (reprinted from the daily reports during the week) is by a Welsh journalist and has a lot of detail comparing the “Irish Eisteddford” with similar events in Wales. There is no mention of the competitions for pipes or wire-strung harps, though we do get a tantalising snippet about Owen Lloyd: “they consider him an Irishman, though his father and mother were Welsh people and he was born in Wales. And even now, after adopting Ireland as his country, and after having been adopted by Dublin people as an Irishman, he still is able to talk a little Welsh.”

I found a report of a professional engagement in 1849. This would be nine years after he was discharged from his studies and got his harp; he would have been in his late 20s by this time.

Geraldine House is just north east of Athy. I have not been able to track down T. Fitzgerald, who would have been born in 1828.

I have been tracking down the gold trophy that was to be presented at the Feis Ceoil on 22 May 1897. The earliest reference I have seen is in a report of an early meeting of the Feis Committee in Dublin on 15 November 1895, 18 months before the first Feis was held:

I also found a drawing of it in a contemporary newspaper article. The drawing is “full size” but I don’t know what the original size was – it is one column of the newspaper so maybe 5 to 7cm wide?

The newspaper article was written two weeks before the competition; the text is interesting, suggesting that the names of the competitors for the “archaeological” competitions behind closed doors at the Molesworth Hall were already known and the committee had already failed to find any harpers, and decided to re-purpose the trophy:

There was obviously some disagreement about the awarding of the gold harp, since Simpson wrote a letter to the Daily Independent (Wed 23 Jun 1897 p4) explaining that it was not his harp that had been presented to Signor Esposito, but a different gold harp; Simpson says that because his harp trophy was “not allocated as a prize in any of the competitions, I absolutely declined to allow it to be allocated after the competitions were over”, and says that he had agreed with the Committee to hold it over until the next year’s Feis, and then to award it to “purely Irish work by an Irish musician”. Here we see a snippet of Simpson’s motivation, but we also see that the traditional harpers have been totally sidelined by this stage.

I think we can see this trophy as clearly modelled on the silver and gold harp trophy (ariandlws) awarded to the winning harpers at the Welsh Eisteddfordau. The oldest and most famous of these is the Mostyn silver harp made in the 1560s and still kept by the Mostyn family; there are nice photos online of another silver harp trophy from the Rhuddlan Eisteddford in 1850. As mentioned above, the Feis Ceoil in 1897 was consciously modelled on the Welsh Eisteddford; a very interesting article tracking the general influence of the Welsh language and cultural revival on the Irish is Caoimhín De Barra, ‘A gallant little ‘tírín’: the Welsh influence on Irish cultural nationalism’, in Irish Historical Studies vol 39 no 153, May 2014.

I was looking at the article in the Celtic Monthly no.10 vol.VI, Jul 1898, p200 (online at the NLS), about Emily MacDonald and the playing of the gut-strung lever harp in Scotland. The article says “… At last Mòd she was the recipient of a handsome Gold Brian Boru harp from the delegation of the Irish Feis Ceòil”. The last Mòd before the article was written had been held in Inverness in September 1897; do we understood that the Feis committee decided to take Simpson’s trophy with them to Scotland, and present it to Emily MacDonald? Or were there more than one of these medals?

The research by Lia Lonnert and Helen Davies has been published as chapter 3 of Harp Studies II edited by Helen Lawlor and Sandra Joyce, published by Four Courts in 2024. The chapter is titled ‘When thy slender fingers go forth on the wire: the visit of Swedish harp virtuoso Adolf Sjödén to Ireland in 1879’ and concentrates (of course) on Sjödén and his work. The chapter is almost entirely focussed (as was Sjödén) on the classical side of things, and the classical re-imagining of Irish music. There is brief mention of Paul Smith on pages 83 and 84, without really any context about him as a tradition-bearer in the 1790s; he is contextualised only by reference to the Belfast Harp Festival of 1792. The footnotes refer to Sjödén’s concert programmes which are in Heidelberg University Library (shelfmark G9203-2), and which mention Paul Smith by name.