Hugh Higgins was a traditional Irish harper in the 18th century. He is said to have died in 1796 so he only just gets a place in my Long 19th Century project, looking at harpers who were active from 1792 through to 1909.

We first meet Hugh Higgins towards the end of his life. In 1792 he was said to be aged 55, and blind, and he was working as a professional traditional Irish harper, travelling with at least one servant. He must have heard about the advertisements for the meeting of harpers that was planned for July 1792.

In Belfast, 1792

Hugh Higgins travelled to Belfast for the meeting of the harpers in the old Exchange Rooms, from Wednesday 11th through to Saturday 14th June 1792.

… The Harpers were assembled in the Exchange-Rooms, and commenced their probationary rehersals on Wednesday last, and continued to play about two hours each succeeding day till Saturday; – after which the fund, arising from subscriptions and the sale of tickets, to a considerable amount, was distributed in premiums (or donations) from ten to two guineas each, according to their different degrees of merit …

The Northern Star Wed 18 Jul 1792

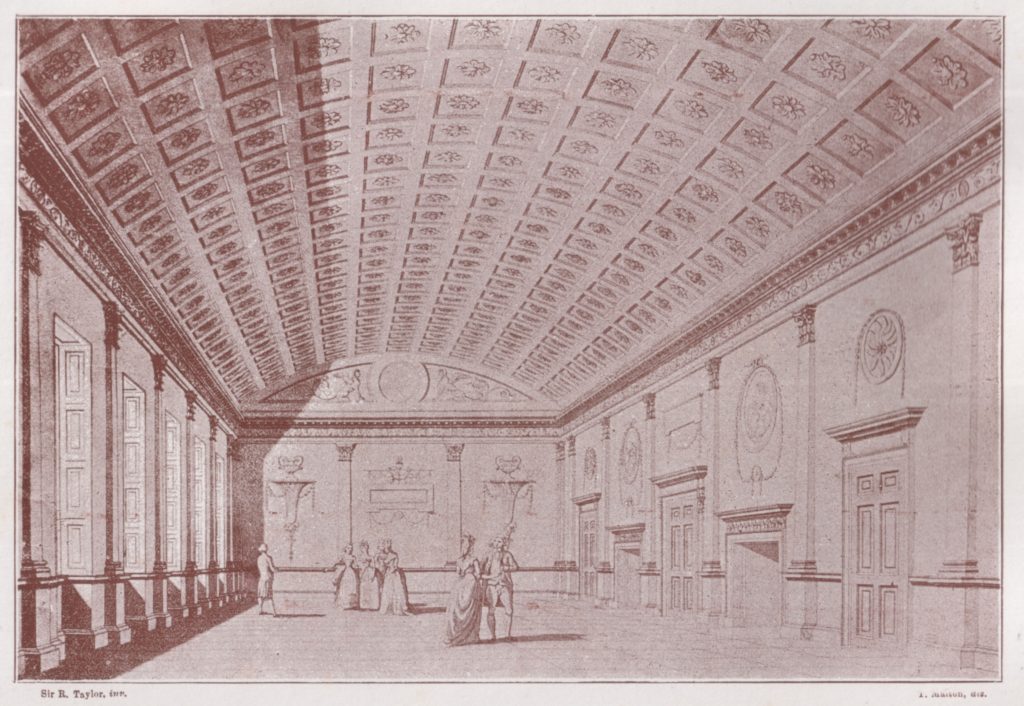

My header image shows a 1793 engraving of the interior of the upstairs room in the old Exchange, where the harpers had met.

We have a very evocative and atmospheric description of the event from “a letter written by a Belfast lady, August 3rd, 179[1]” – though the year is obviously wrong and should read 1792. The letter describes the Bastille celebrations on 14th July, but also mentions her attending the harpers meeting:

…And so you must have an account of the Harpers too. I was hearing them one day; I like them very much. The Harp is an agreeable soft musick, very like the notes of a Harpsichord; would be very Pleasant in a small room. There were eight men and one woman, all either Blind or Lame, and all old but two men. Figure to yourself this group, indifferently dress’d, sitting on a Stage erected for them in one end of the Exchange Ball Room, and the Ladies and Gentlemen of the first fashion in Belfast and its Vicinity looking on and listening attentively, and you will have an Idea of how they look’d. You can’t imagine anything sweeter than the Musick; every one played separately. The money that was drawn during the four days that they were here was divided among them according to their merit. The best Performer got ten Guineas and the worst two, and the rest accordingly. Now, how do you like the poor old Harpers?

Robert Young (ed), Historical Notices of Old Belfast… (1896) p272-3

Now this letter only mentions nine harpers, so presumably one did not play the day the lady was there. The newspaper on the 3rd day (Friday) published a list of 10 Irish harpers who attended and the tunes they had played, plus also mentioning one Welsh harper. Hugh Higgins is sixth on the list:

HUGH HIGGINS (blind) from the co. Mayo, aged 55.

Belfast News Letter, Fri 13 Jul 1792 p3

Played – Madam Cole – Carolan.

So we can instantly calculate that if he was 55 years old in July 1792, he must have been born in 1736 or 1737.

In 1840, Edward Bunting printed basically this same text from the Belfast News Letter, but he added a couple of bits of extra information. I mentioned this already on my write up of Rose Mooney, because the newspaper does not give her age, but Bunting does. In this case Bunting gives us extra information about Higgins:

HUGH HIGGINS, (Blind,) from the county of Mayo, aged 55, played “Slieve Gallen,” ancient, and “Madam Cole,” (Carolan.)

Edward Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland (1840) introduction p64

We can discuss these tune references later. I used to assume that Bunting was merely reprinting the newspaper article, but now I wonder if both the newspaper and Bunting were reprinting some kind of programme sheet or press release that is now lost.

of St John’s College, Cambridge

William Carr was one of the harpers who played, and he remembered 11 harpers in total, including the Welsh harper, Williams. This information was told to the English traveller John Lee in Drogheda on Wed 18 Feb 1807, and Lee wrote it into his travel journal:

Hugh Higgins from Connaught (P[layed] very well and had an Elegant harp) (Dead)

Angela Byrne (ed), A scientific Antiquarian and Picturesque Tour (2018) p303

Carr’s information is especially valuable as being “insider” opinions from a tradition-bearer. When Carr says that Higgins “played very well” we have to pay attention because, unlike most of the commentators who judged the playing of traditional harpers, Carr was also a player and knew what the traditional norms were. It is also interesting to see Carr’s opinion of Higgins’s harp, that it was “elegant”. And of course the note that Higgins was dead just confirms that he was dead already by Feb 1807; we have other information (see below) that he died in 1796.

The Northern Star newspaper concludes with a snippet of information about follow-on work from the meeting:

… Professional gentlemen are now employed in taking down some of the above airs, and, it is said, they have a pleasing effect when applied to the harpsichord, violin, &c.

The Northern Star Wed 18 Jul 1792

Meeting with Edward Bunting

The young classical musician, pianist and church organist, Edward Bunting, was hired by the Gentlemen organisers to write down the music of the harpers and arrange it for publication. It is usually stated that Edward Bunting did his live collecting during the four days of the meeting, from Wednesday 11th through to Saturday 14th June 1792, but as I discussed in my post on Bunting’s Collecting Trips, I am very suspicious of this and I am not sure if Bunting did any actual collecting of notation during those four days. But he certainly would have collected tune titles, and met the harpers, and perhaps started planning to visit them afterwards.

Our great problem with Bunting’s work is that he was totally focussed on his project to “save” the most ancient strands of Irish music, by de-traditionalising it and arranging it as classical music for piano-forte; and although we are incredibly lucky that a lot of his rough field notes and intermediate working notebooks survive, he was very bad at record-keeping and so it can be very difficult if not impossible to properly follow through his working methods or to find out where published statements derive from.

Bunting mentions Hugh Higgins a number of times in his unpublished manuscripts, and in his published printed books. Most of these mentions are very non-specific, and don’t tell us what Higgins was doing after 1792. But we need to go through them to see what they can tell us anyway.

Tunes tagged with Higgins’s name

Bunting claims to have collected a number of tunes from the playing of Hugh Higgins. If any of these claims are true, these collecting sessions must have occured between July 1792, when they first met, and 1796, which is the year Higgins is said to have died.

Most of Edward Bunting’s field collecting apparently happened in just three separate years, 1792, 1796, and 1802 (see my chart of attributions per year). However, most of the attribution tags were written into piano arrangements much later, in the late 1830s and early 1840s, about 40 years after the actual collecting trips. Because of this long period of time and because of the apparent complete lack of record-keeping in between, I am very suspicious of these late attribution tags, and unless there is some other corroborating evidence I tend to regard these as most likely erroneous, whether due to confusion or possibly even deliberate invention of attributions.

We do have a few attribution tags written in the 1790s, broadly contemporary with the collecting process. These mostly come from the 1798 unpublished piano manuscript (QUB SC MS4.33 parts 3 & 2), with one in the actual field collecting booklet from 1792 (QUB SC MS4.29)

The 1792 field notebook attribution tag is in QUB SC MS4.29 page 28/28/37/f13v. This page contains what appears to be the live field transcription notation of the tune of Táim i mo chodladh. At the bottom is written “From Hugh Higgins / in 1792”. Now of course we can’t be sure that this attribution information was written in at the same time as the notation and the titles, but it seems plausible. I wrote up this page as part of my Transcriptions Project a few years ago. Edward Bunting never developed this version of Táim i mo chodladh and so we don’t have any attribution tags from later piano arrangements, because there are no later arrangements of this version. All of Bunting’s later developments of Táim i mo chodladh are derived from a different live transcription notation that he made from the playing of Dennis Hampson.

There is a second page in the live transcription pamphlets which has the name “Higgins” on it. QUB SC MS4.29 page 152/149/158/f74r has the live transcription notation of the tune of My Lodging’s Uncertain, and at the bottom of the live field transcription page, amongst the doodling, is the name “Higgins”. This tune is later tagged as having been collected from Hugh Higgins (see below) but I don’t know if this doodling is connected to that or is just random.

In Edward Bunting’s live field transcription pamphlets there is a page which contains a tune list headed “from Hugh Higgins”. Some of the list is very hard to make sense of and the words in square brackets here are just my guess and are probably wrong.

From Hugh Higgins

John Jones Carolan [ill]

Grah ga niste very old

Cathleen ne Oullahan

[Mol] [London]

Slumber Maggenis CarolanJones a Taylor made C.

Queens University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.29 p79/75/084/f37r

a suit of Cloths [and] did not

Charge him any thing for it

Apart from the hard-to-read line which I don’t understand, we can identify here four tune titles. I don’t know what tune “Slumber Maggenis” is; the other three tunes appear as live transcription dots in the manuscript. However they don’t form a group and so I don’t necessarily think this list refers directly to versions of tunes transcribed live from Higgins’s playing. John Jones is on p164; Grádh gan fhios is on p221; and Caitlín Ní Uallacháin (Kitty Nowlan) is on p84 and also what looks like a copy from elsewhere on p202. The list could represent a set of tunes that Higgins played, or tunes that other people told Bunting that he could get from Higgins; or something else.

On the page about Táim i mo chodladh I discussed two possible groups of live transcriptions that seem to have been written by Edward Bunting live from the playing of Hugh Higgins. You can understand these groupings if you look at my ms29 text transcript and my tune list spreadsheet.

I am thinking there is a possible group which includes Toby Peyton on p.26 and Táim i mo chodhladh on p.28. Then there is Burns’s March on p.30 and A chailíní, an bhfaca sibh Seoirse on p.32. This Burns’s March transcription is usually claimed for Hampson, but I am seriously wondering if Bunting has made an attribution error and if in fact this live transcription comes from Higgins. And the Cailíní transcription here is different from the version he got from Hampson, and so I wonder if it also may come from Higgins. But this is very speculative.

There is another more convincing group from p.78-90, which includes the tune list we discussed above, though you’ll see that not all the tunes on the list are in this group: Mild Mable Kelly, Sliabh Gaillean (Slieve Gallen), Cupán Uí Eaghra (O’Hara’s cup), Caitlín Ní Uallacháin (Kitty Nowlan), Thugamar féin an samhradh linn (with variation), Rois Dilloun / Young Lady Dillon, and Dr. Hart.

(Each of these links to a tune title takes you to my commentary on the manuscript page including a facsimile of the live trancription page and a machine audio of the transcription dots.)

In 1797, Edward Bunting published his first printed collection of tunes, but he did not include any attribution information in the 1797 book; in fact he does not name any of the traditional harpers he had met and collected tunes from. In 1798, he compiled a new 2-volume piano manuscript, but which was never published. The unique original is preserved in Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections. MS4.33.3 is vol. 1 of this 2-volume piano manuscript; MS4.33.2 is vol 2. At the end of MS4.33.3, Bunting has written a title-page calling the work “Ancient and Modern / (i.e. Carolan’s) / Irish Music / Volume 1st / (not published) / Containing 50 tunes / For the Harpsichord or Piano Forte / by E Bunting Octr 30th 1798”. From our point of view the piano arrangements are not interesting, but what is important is that most of the piano arrangements have attribution tags written above or below them. Now of course we cannot be sure that these tags were written into the book in 1798 at the same time as the notation, but it seems plausible that many or most of them might have been.

I did some sorting and filtering of my tune list spreadsheet and I am counting 13 or 14 tunes in the 1798 piano manuscript which have tags saying they are “from” Hugh Higgins. The uncertainty depends if you think Madam Bermingham and its jig count as one tune or two.

Jig to Madam Judge (MS4.33.3 p4)

Mild Mable Kelly MS4.33.3 p29-30)

Sliabh gCallann (MS4.33.3 p32)

Cupán Uí Eaghra (MS4.33.3 p34-5)

Dr. Hart (MS4.33.3 p36-7)

Miss Hamilton (MS4.33.3 p41)

Bruach na Carraige Báine (MS4.33.3 p48)

Madam Maxwell (MS4.33.3 p52)

Madam Bermingham and jig (MS4.33.3 p54-5)

Sín Síos an Ród a d’Imigh Sí (MS4.33.3 p60)

An gearrán buidhe (MS4.33.2 p11)

Sín Síos agus Suas liom (MS4.33.2 p12)

My Lodgings uncertain where ever I go (MS4.33.2 p28)

Planxty Reynolds (MS4.33.2 p32)

Does this represent some kind of list of Hugh Higgins’s repertory? Or is this all spurious and misleading? I assume most of the harpers knew most of the repertory, and so I would imagine Hugh Higgins knew or played all of these tunes and all of the others anyway.

Bunting later gave attributions to different informants against half of these tunes, which I think just goes to show that these attribution tags on their own are a bit meaningless. Even more worrying, two of these 1798 piano arrangements have multiple attribution tags, as if Bunting was combining different versions, or perhaps inventing attributions. I really don’t know.

Muh later, in the late 1830s and early 1840s, Bunting wrote a whole load of attribution tags against different piano arrangements. Some of these tags are in new piano arrangements from the late 1830s; some are in the 1840 printed book; and some were written in the early 1840s into Bunting’s own copies of his old 1797 and 1809 printed books, as part of a plan to re-publish the old collections. About fifty tunes in total in Bunting’s manuscripts and printed books have “Hugh Higgins” attribution tags, but apart from the ones discussed above these attributions were all written down fifty years later, based on unknown information, memory or invention, and so I don’t see any need to take them seriously. It is all so unsatisfactory I think we can move on from these. If you want to follow them up they are all in my tune list spreadsheet.

Some of these late attribution tags have dates written in as well as Hugh Higgins’s name. Ten of the late attributions have a date beside Higgins’s name; the date in all 10 cases is 1792. So (apart from the fact that we are very doubtful about these late attribution tags) we might wonder if indeed Bunting only met Higgins in the summer of 1792, and did not meet him in a subsequent year.

The only other tune we should discuss here is Madam Cole, which Higgins is listed as playing in Belfast in 1792. Madam Cole is a tune usually attributed to Carolan; it is no.15 in Donal O’Sullivan’s Carolan. We have what looks like a live transcription notation of a harper’s performance of Madam Cole, done in the 1790s, which you can see in QUB SC MS4.29 page 149/146/155/f72v. I have already written up this live transcription notation as part of my Transcriptions Project. Bunting only gives us one attribution tag for this tune, written down 50 years later in the early 1840s, where he tags it as coming from Arthur O’Neil. But I don’t really believe these late tags. I note that there is a second title at the top of the transcription page of Madam Cole, saying “Miss Hamilton by Lyons”, presumably as a reference to another tune or another live transcription; and you can see if you check my ms29 text transcript and my tune list spreadsheet that this live transcription of Madam Cole sits close to the live transcriptions of Miss Hamilton and My Lodging’s Uncertain, which may have been notated live from Higgins. But they may not; they may all be from O’Neil, or from another harper. I don’t know how we can tell, because Bunting’s rough notes are so disorganised and his record-keeping is so poor. And I don’t think it even matters that much, because we can be fairly sure these live transcriptions did come from a harper, and it seems likely that Hugh Higgins knew and played most of these tunes anyway.

Other information in attribution tags

Some of Bunting’s attribution tags include other fragments of information, which we should look at to see if we can get more information about Hugh Higgins from them.

The attribution for Sliabh gCallann (MS4.33.3 p32) reads “From Hugh Higgins – died in 1796” which is interesting in that it gives us his year of death. I am not sure we have any corroborating evidence for this date so we can cautiously take it at face value, especially as the attribution tag may have been written in 1798, just a couple of years later.

The attribution for Bruach na Carraige Báine (MS4.33.3 p48) reads “From Hugh Higgins Singing” which is very interesting, as if Bunting is saying that he made the initial field transcription (which this 1798 piano arrangement is based on) from a vocal performance by Higgins. We might assume that Higgins was singing this song in Irish. I am not aware of any other information about Higgins singing.

The method of playing

In his very important chapter II, “Of the method of playing and musical vocabulary of the old Irish harpers” (1840 intro p.18-36), Bunting gives descriptions of how the harpers played, and the tables of fingering techniques; this chapter of the 1840 book has been one of the key sources for Sylvia Crawford’s work over the past few years to rediscover and reconstruct the way of playing the traditional wire-strung Irish harp. On p.20, Bunting. tells us that Higgins was one of his sources for the fingering techniques and the Irish-language names for them. But it is not possible to untangle what information came from the different harpers; Bunting says that “they exhibited a perfect agreement in all their statements”.

Other information in Bunting’s manuscripts and printed books

There is actually surprisingly little information about Hugh Higgins in Edward Bunting’s writings. The main information (apart from the attribution tags) is in the introduction to the 1840 book. Edward Bunting makes a brief comment about how Hugh Higgins was more smartly dressed than the other harpers:

A few of them made an attempt at splendour, by wearing silver buttons on their coats, particularly Higgins and O’Neill; the former had his buttons decorated with his initials only …

Edward Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland, 1840 intro p65)

This raises the interesting question of what Hugh Higgins called himself. Since the Gaelic Revival in the early 20th century, it has been occasionally suggested that the 18th century (and sometimes the 19th century ones) would have used the Irish form of their names; in this case I think Aodh Ó hUiginn. But I am thinking that it is perhaps more likely that the “initials” on Hugh Higgins’s silver buttons may have been “H H” perhaps like this 1780s silver hunt button. We would need to study the history of Anglicisation of Irish language names to get more of a sense of this. Because almost all of our source texts from the 18th and 19th century are in English, the names of the harpers are given in English form. There is a column in my timeline of Irish harpers in the long 19th century showing whether that have Irish or not. For most of them we have no information.

The only other information Bunting gives us is in the 1840 intro p79-80. This all seems to be derived from and somewhat garbled from Arthur O’Neil’s Memoirs; Bunting gets some key information confused. We should ignore Bunting’s garbled account and look at what Arthur O’Neil has to say, both directly about Hugh Higgins, and later on about Higgins’s role in a story about John Keenan.

Arthur O’Neil’s Memoirs

I think that the harper and tradition-bearer Arthur O’Neil is our main source of biographical information about Hugh Higgins. This information all relates to Hugh Higgins’s birth, training, and professional career, which is before the beginning of our Long 19th Century study period in 1792, but we should just look at it because it tells us about Hugh Higgins’s character.

In the rough versions of Arthur O’Neil’s Memoirs, compiled in about 1808, Arthur O’Neil writes:

I knew and often met a Hugh Higgins and in all his peregrinations he supported the Character of an Irish Gentlemanly Harper. I will not sett him down with the Toll: Lol’s: by any means. He was uncommonly Genteel in His manners, and as to his Dress I am informed that he spared no expence in purchasing clothes, But as a Blind man is no Judge of Colours “he was obliged to take his Guides Word for his fancy. – He travelled in such a manner as does and will do Credit to an Irish Harper. Hugh was born in a place called Tirawley in the Co. of Mayo of very <decent>

Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.46 p16 (032)industriousparents. His mother name was Burke, but loosing his sight at an early Period, they had the good sense to put him to music, and they prefered the Harp to the Bag-pipe on which my dear Deceased friend made such a proficiency as to Rank him much and very much, above the Description of performers called <in> the last of mycuriousobservations – that is ——— Toll: Loll:

“Tol lol” is an English slang abbreviation for “tolerable”, and seems to be Arthur O’Neil’s way of describing a musician as being worse than average. By saying Hugh Higgins is “by no means” one of the tolerable ones, and “much and very much above” them, O’Neill seems to be saying he was much better than the others.

Anyway, this slightly scatty description is toned down a bit in the neater revised version of Arthur O’Neil’s Memoirs:

I knew and met Hugh Higgins in all my peregrinations, he supported the Character of a Gentleman Harper was uncommon Genteel in his manners, and spared no expence in his Dress. He travelled in such a manner as does and will do Credit to an Irish Harper

Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.14 p20 (023)

Hugh was born in a place called Tyrawly in the County of Mayo of very decent parents, his mothers name was Burke. He lost his sight at an early period, and was bound to learn the Harp, on which mydeardeceased friend made such a proficiency as to rank him one of the best I ever heard.

I think it is significant that Arthur O’Neil says that Higgins played well, that he was “one of the best I ever heard”. We can compare this to the opinion of another professional traditional Irish harper, William Carr (see above), who said that Higgins “P[layed] very well”. We can also note that while these two harpers appreciated Higgins’s playing, Higgins was not placed by the Gentlemen who awarded the prizes at Granard or Belfast.

Arthur O’Neil gives us some information about what Hugh Higgins had been up to in the 1780s, at the Granard balls. Arthur O’Neil misremembered the dates of the three balls, guessing that they were three years earlier; I have worked out the correct dates from the contemporary newspaper reports. O’Neil tells us that Hugh Higgins was at the first Granard Ball (Tuesday 31 Aug 1784). The following year, O’Neil tells us that Higgins was at the second Granard ball (Monday 1st August 1785), though he adds that “Higgins got some how huffed and retired without playing a single tune.” (Memoirs neat version p46). O’Neil also lists Higgins as attending the third Granard Ball (Tuesday 1st August 1786). Anyway this is before the start of our study period.

Rescuing John Keenan from Jail

Perhaps the most fun story about Hugh Higgins is how he rescued another blind harper from jail. Unfortunately the story is not dated; it is from Arthur O’Neil’s Memoirs which were written c.1808. I think it is most likely that it dates from before our study period, perhaps in the 1750s, 60s or 70s.

This story has been told and re-told based on Edward Bunting’s paraphrasing of the story in his 1840 book (intro p79); but as discussed above Bunting misread Arthur O’Neil’s manuscript, and got the identity of the jailed harper wrong. Bunting says the man in jail was Owen Keenan, who was Arthur O’Neil’s old harp teacher; but O’Neil is very clear that the man in jail was John Keenan, a pupil of Owen Keenan:

John Keenan was born in Augher in the County of Tyrone, was born blind. He was a school fellow of mine learning the Harp in Augher.

Arthur O’Neil, Memoirs neat version (QUB SC MS4.14 p85-6)

Unfortunately Charlotte Milligan Fox relied on the rough Memoirs for her 1911 Annals of the Irish Harpers (p127) and so when she tells the story, she used the 1840 introduction with the wrong harper named. It was not until 1958 that the story was published with John Keenan’s name attached to it, in Donal O’Sullivan’s Carolan (vol 2 p181)

The story about Hugh Higgins is told by Arthur O’Neil, who says that John Keenan

… went to Mr. Stewarts of Killymoon, and fell in Love with a French Governante that was there, and they became of consequence very great. He next went to the House of a Gentleman in that neighbourhood, and in a few nights he contrived to visit Madam, and contrived also to come back to Killymoon and brought with him a 19 foot Ladder, and put it up against her bedchamber window, then climbed up and tumbled into bed, however Madam was not in bed, but another old woman, who screechd out and made an alarm and poor Keenan, was taken and committed to Omagh Gaol. When Mrs Stewart heard of it, she made some noise not knowing the reason. Miss Stewart, a young Girl exclaimed “Oh many a night he slept with Mrs Bennatte (the Governante) “and me”.

Arthur O’Neil, Memoirs neat version (QUB SC MS4.14 p86-88)

When in Gaol Hu: Higgins before named, came there to visit him, not thinking his crime dishonourable it being a love affair, and after some conversation Keenans liberation was planned. Higgins sent out for some whiskey, and the Gaolers wife who doated on it, the Turnkey and other prisoners fell to drink and all got drunk, except Keenan and Higgins. the Gaoler’s wife got so Drunk she went to bed, the Gaoler being from home, and Keenan got into her Room and stole the key of the Gaol out of her pocket, then opened the Door & took Higgins’s Boy with him to lead him, and left Higgins behind him in his place. He then crossed the River with The boy on his back, and went directly back to Killymoon again to see the Governante. He was again committed for the Ladder business, but at the assizes the Judge ordered him out of the Dock thinking it impossible a blind man could himself alone manage the Ladder at the window in the manner before mentioned. Keenan however married the Governante, and after divers journeys thro’ this Kingdom, they went to america together where she turned whore,and where poor Keenan died.

This story (and indeed all of the other information about John Keenan) does not appear in the rough version of the Memoirs (QUB SC MS4.46). I don’t think this tells us very much about Hugh Higgins, and the story does not tell us the most important part of Higgins’s role in this – how did he get out of the jail and back to his servant boy?

Killymoon Castle near Cookstown was the seat of the Stewart family; but the assizes and jail seem to have been in Omagh town. I have added both to this map though in the story Higgins does not go to Killymoon, only to the jail in Omagh.

Finally, the name “Higgins” appears twice on the loose sheet associated with Arthur O’Neil which became separated from the rest of the Memoirs (Belfast Central Library, FJ Bigger Archive, Envelope V6), but there is no other information about Higgins on the sheet apart from the name “Higgins” in the two lists of harpers. So this is kind of useless.

His harp

We have only one piece of direct evidence about the harp that Hugh Higgins played. The harper and tradition-bearer William Carr said that Hugh Higgins

… had an Elegant harp

Angela Byrne (ed), A scientific Antiquarian and Picturesque Tour (2018) p303

This does not give us much to go on. We can however be sure that it was a full-sized traditional wire-strung Irish harp, because that is the kind of harp that all of the traditional Irish harpers were playing in the 18th century.

There is some very circumstantial information about a harp that might possibly have been Hugh Higgins’s. I almost skipped this information because the connection to Higgins is so uncertain, in fact almost non-existent, but I need to put it somewhere so here will do.

The information is in Edward Bunting’s 1790s live transcription pamphlets, on the same page as where he has made what looks like a live transcription of the variation to Sliabh gCallan. Now we are told by Edward Bunting in his 1798 piano manuscript, that he had collected the tune of Sliabh gCallan from the harper Hugh Higgins (QUB SC MS4.33.3 p32). And the live transcription notation in QUB SC MS4.29 pages 80/76/085/f37v and 81/77/086/f38r sits in a group of tunes from page 78 to page 90, which I have suggested above may represent a group of live transcriptions taken from Hugh Higgins in 1792.

At the bottom of page 81/77/086/f38r is a diagram showing the notes of a harp. Now based on my speculation and suggestions above, it is possible that this could be a diagram of the notes of Hugh Higgins’s harp. But I want to make it clear that there is no real evidence for this; the diagram could have been entered by Bunting into a space in his pamphlets at any time after the live transcription session of this tune; and this tune might have been transcribed from the live performance of any harper.

But we should look at the diagram anyway, and say something useful about it.

The notation is divided by a bar line between the “sisters”, the two strings tuned to g below middle c. The very lowest string is labelled “organ”; I think this might be the name for the lowest three or so strings. Then we see the gapped bass, and the whole of the bass is labelled “right hand”, and the treble is labelled “left hand”. There is also the note “harp al[w]ays tuned by the sisters”.

I assume that this is a field notation of a harper showing the range and disposition of their harp, and the words are a transcription or paraphrase of what the harper said to explain how the harp was played and tuned and what the strings were called.

This bass range and disposition looks typical of a full sized wire-strung Irish harp in the 18th and 19th centuries. I assume that the very lowest string may be notated an octave higher than its actual speaking pitch. We can compare this chart with the tuning sequences noted by Edward Bunting live from probably a different harper, on QUB SC MS4.29 page 150/147/156/f73r which I have previously written up. The bass disposition here has the same number of strings, but the gap is slightly different – here the gap is between B and D (no C), but on the tuning chart the gap is between A and C (no B). Unfortunately neither this chart nor the tuning sequence tells us the treble range or string count.