William Carr was a traditional Irish harper at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century. This post is to gather everything I can find out about him.

Sources of information

I think we have three main sources of information for William Carr. The first is the information about the famous meeting of the harpers in Belfast in July 1792; this information was published in the newspapers at the time, and was re-printed by Edward Bunting in 1840.

The second is a description and portrait of Carr from an English traveller who met him in 1807. Sylvia Crawford had been looking out for information about Carr as part of her research on Patrick Quinn, and she showed me this account.

The third is a couple of mentions of Carr in later newspapers. There may be more out there to be found.

Birth and early years

William Carr was said to be aged 15 in July 1792, and so we can calculate that he was born in 1776 or 1777. All of our sources agree that he was from Portadown.

Education

We have John Lee’s version of Carr’s own testimony:

He had bad eyes when young and began learning music when about 12 years old, “thinking it might be of some service to him as well as amusement (ie he was afraid he shd go blind and ∴ learnt to play the harp) He was always fond of it. He had some instruction from Arthur O Neil and also from Patric Quin of the Co. of Armagh

ed. Angela Byrne, A Scientific, antiquarian and picturesque tour – John (Fiott) Lee in Ireland, England and Wales, 1806-7. Routlege 2018, p.302-3

When Carr was 12, the year would have been 1788-9. It is not clear how this tuition worked – I think it was normal for a young boy to go and study full time with a teacher or master, a bit like an apprenticeship. Arthur O’Neill mentions trying to set up formal tuition later on (I discuss this in my post on Bridget O’Reilly). I think it usually took at least two years of full time study to become a professional harper, sometimes as much as four or five.

Carr did eventually go blind as an adult aged about 28 or so, in c.1805, so his long-term plan seems sensible.

Going to Belfast in 1792

William Carr went to the famous meeting of the harpers in Belfast in 1792. His name appears in the contemporary newspaper accounts of the meeting.

Wm. Carr, from the Co. Armagh, aged 15.

Belfast Newsletter, “From Tuesday July 10, to Friday July 13, 1792” p.3

Played – The Dawn of the Day.

The Dawn of Day is the title of a whole load of different tunes so it is not really possible to say what Carr was playing at the Belfast meeting.

In his conversation with Lee, Wiliam Carr gives a lot more information about his participation in the Belfast meeting.

…in year before rebellion he was at the Belfast Musical Meeting and although but a young hand they encouraged him to play. Quin his master lent him his Harp

ed. Angela Byrne, A Scientific, antiquarian and picturesque tour – John (Fiott) Lee in Ireland, England and Wales, 1806-7. Routlege 2018, p.302-3

…

William Cair of Portadown Co Armagh. He recd 2Gs. He was but a beginner and they gave him he says this to encourage him

This gives us some very immediate first-hand information about the meeting. “Quin his master lent him his harp” – as I have said before, it was normal for harp students not to have their own harp until they had finished their studies and been discharged as a professional harper. I assume Quin may have taken the young Carr along with him as a kind of apprentice. Carr also says that the meeting organisers gave him a prize of 2 guineas (£2 2 shillings) “to encourage him” – it must have been an excitement for the gentlemen to see a young beginner learning the harp, to take it forward for future generations.

Angela Byrne in her edition of Lee points out that the Rebellion was in 1798 but the Meeting was in 1792, so it is not entirely clear what Carr was talking about here.

Carr’s opinion of the other harpers

As part of his conversation with John Lee about the Belfast meeting, Carr listed all the attendees along with his opinion of them. This was in 1807, fifteen years after the event.

He recollects that there were 11 Harpers and believes these were all

ed. Angela Byrne, A Scientific, antiquarian and picturesque tour – John (Fiott) Lee in Ireland, England and Wales, 1806-7. Routlege 2018, p.303

Charles Fanning Co Cavan (got 1st prize, 10Gs. Was best player by much)

Patric Quin Co Armagh (5Gs 2 Prize)

Arthur O Neil Co Tyrone

Williams a Welsh man (played very well on a Welsh Harp. They were in doubt whether to admit him, but on his playing all Irish tunes they did 5Gs.

Hugh Higgins from Connaught (P very well and had an Elegant harp) (Dead)

Daniel Black (dead since)

Charlie O Byrn fm Leitrim (played worst) He was originally but the servant to a harper and always carried his Masters Harpbut heand he only took a fancy to learning as well as he cd, never well Educated for it

Rose Moony from West Meath (a woman played very well and better than some

William Cair of Portadown Co Armagh. He recd 2Gs. He was but a beginner and they gave him he says this to encourage him

Dennis Hampton Co Derry. Man mend by Miss Owenson, he did not play so very well as some and was then very old.

James Duncan Co Down played very Moderately (since Dead)

Cair only knows of one more harper in the Kingdom than the survivors of these and he is an infirm old man and was sick at that time His name is Patrick Lynder Co Armagh and he could not attend. He thinks there are no more respectable ones in Ireland or he shd have heard of them.

This is all fascinating stuff and includes brand new information about many of these harpers. It is also fascinating as being an “insider” opinion of the harpers, instead of what we usually get, an outsider’s view.

I also find it interesting that Carr says that he thinks there are no more respectable harpers, or he should have heard of them. 1807 is the year before the Belfast Harp Society started, but even so there were other harpers around. I have already discussed Bridget O’Reilly who I think was out playing by then. There may have been other young students of Arthur O’Neill’s experiments with running harp schools. I think Dominic O’Donnell was still alive in Mayo. We have one enigmatic reference to Hennesy in Dundalk in 1804, though he may have been dead by 1807. Kate Martin may also have been dead, and Carr may never have met her since she is said not to have travelled outside County Cavan. There was also Thomas Shea in Tralee, but he was very old in 1792 and may have died soon after.

Ignored by Edward Bunting

Edward Bunting pretty much ignored William Carr. I think this is probably because Bunting was obsessed with the Irish music being “Ancient” and either dying or dead, and the young harp student Carr would have been a challenge to that world-view. Bunting did not collect any tunes from Carr, or any information about how he was learning or taught the harp.

In Bunting’s printed books, the only mentions of Carr are in the 1840 book, on page 75 which is copied from the 1792 Belfast Newsletter report on the harpers gathering, and then a very brief note on page 82 which just repeats the age and town and gives no further information. The only mention in Bunting’s unpublished manuscripts I have found is a reference in Collette Moloney’s Introduction and Catalogue, which mentions a list of harpers in QUB SC MS4.13 p.45. The list gives the name and place of each harper; it includes “James Carr Portadown” which I assume is our man. MS4.13 is a large piano album, it is not in Edward Bunting’s handwriting and was compiled by his editors or assistants in the late 1830s in preparation for the 1840 printed book.

Carr’s harp

John Lee gives us some very useful information about Carr’s harp.

His harp was an old thing made accordg to his own directions by a carpenter, he chalked out the plan for him, He gave 2Gs for it when done but the head piece being too straight he was obliged to have another made wh cost him ½ more as he now was obliged to be a new piece. Harp has 32 Strings and they are wires…

ed. Angela Byrne, A Scientific, antiquarian and picturesque tour – John (Fiott) Lee in Ireland, England and Wales, 1806-7. Routlege 2018, p.303

I think that when Lee writes “an old thing” he is not talking about the age of the harp in years, but I think this is an English idiom meaning a poor quality or badly made thing. I think “the head piece being too straight” means the neck was not curved enough, so the mid range strings were likely too long and would snap.

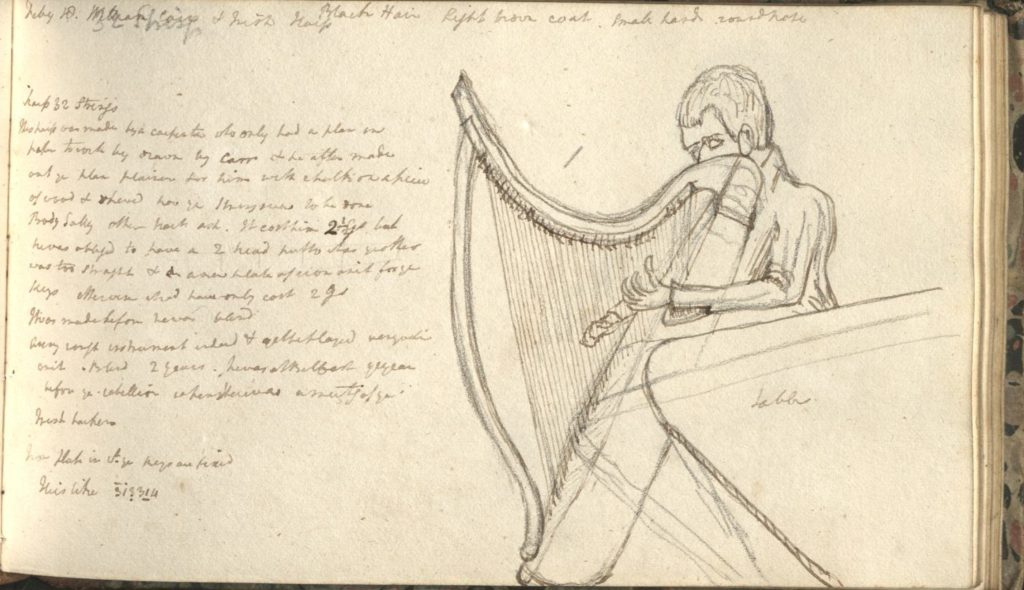

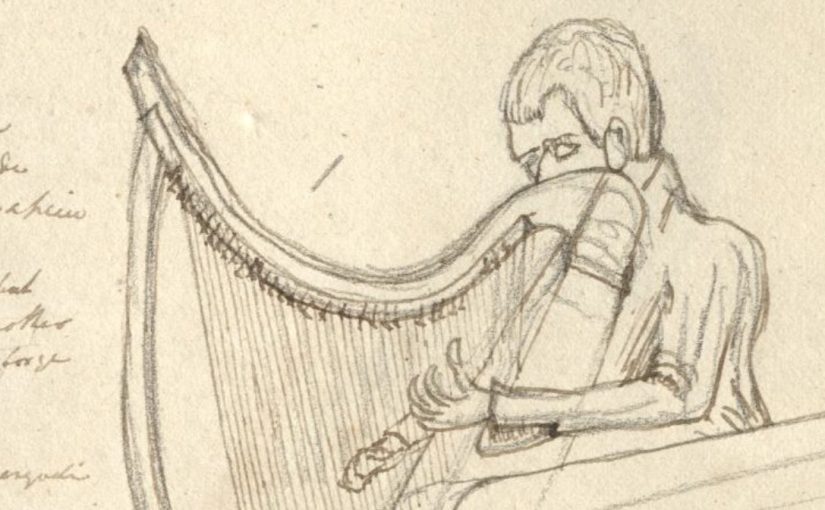

Lee also made a couple of portrait sketches of Carr which show the harp. The first has an extensive caption describing the harp.

Feby 18 William Cair & Irish harp Black Hair Light brown coat small hands. round nose

ed. Angela Byrne, A Scientific, antiquarian and picturesque tour – John (Fiott) Lee in Ireland, England and Wales, 1806-7. Routlege 2018, p.336

harp 32 strings

This harp was made by a carpenter who who only had a plan on paper to work by drawn by Carr & he after made out the plan plainer for him with chalk on a piece of wood & shewd how the strings were to be done

Body Sally other parts ash. It cost him 2½ Gs but he was obliged to have a 2 head put to it as the other was too straight & a new plate of iron for the keys otherwise it wd have only cost 2Gs

It was made before he was blind

a very rough instrument indeed & yet he played very well on it. Blind 2 years. he was at Belfast the year before the rebellion when there was a meeting of the Irish Harpers

Iron plate in wh the keys are fixed

He is like 3̅1̇̇3̣314

To me, it looks like Carr’s harp may have been modelled on the Castle Otway harp which we know that Patrick Quin played in 1809, and which may have been associated with him much earlier (see Sylvia Crawford’s MA thesis p.69). Carr’s harp seems to have had the older style of neck-pillar joint that we also see on the Castle Otway harp. and the number of strings (32) matches the Castle Otway harp with the highest two positions blocked.

We are not told when this harp was made but I would assume it was in the mid 1790s, certainly after 1792 when Carr had to borrow his teacher’s harp, but before about 1805 when Carr went blind. I think it has interesting implications for how there were not harpmakers active at that time; Carr had to go to a carpenter and chalk out the shape of the harp.

The other portraits

The portrait shows Carr slightly concealed by the harp, and also by the corner of a table (helpfully labelled “table” on Lee’s sketch).

There are two other sketches in the notebook, on the next two pages. The second shoes a close up of Carr’s head and the shoulder of the harp, very similar but more scratchy, and captioned “not so like as ye former / Feby 18 1807”. The third shows a different person sitting with the same harp, and captioned “very good profile. Harp inferior to the first / 32 string”.

Later references

We have a few later references to Carr. There is a short list of harpers in the Belfast Monthly Magazine vol 2 No VII p137, 1809 which may include him though not by name:

In the notes, Mr. Arthur O’Neil is described as the only Harper in Ireland. Patrick Quin, of Portadown, has perhaps superior merit to O’Neil. There is a harper in Drogheda. Another, a female, in Dublin, and doubtless several in the South and West.

Belfast Monthly Magazine vol 2 no. 7, 28th February 1809, p.137

I think it is likely that Carr is the “harper in Drogheda”; this is two years after Lee met him in Drogheda.

By 1810, Carr had moved to Dublin where we can find him working in a tavern:

WILLIAM CARR

Saunders’s Newsletter, Saturday 7th April 1810 p2, also Monday 9th April 1810 p2

RESPECTFULLY informs the Public, that he performs on the

OLD IRISH HARP,

At the Old Struggler’s, (Malone’s) Cook-street,

every night.

Live transcription of Carr’s playing

We have a very interesting account of Sir John Stevenson collecting tunes from Carr. The information is given kind of by-the-by in a story about a classical singer, Mr. Spray, making inappropriate political comments.

Mr. SPRAY, the Singer’s liberality

The Irish Magazine and Monthly Asylum for Neglected Biography April 1812 p18

Cahir, an Irish Harper of eminent merit, a native of Portadown, being some time ago in Dublin, was requested by Sir John Stevenson, to go to Mr. Doyle’s in Mountjoy Square, that he might have an opportunity of taking some Irish airs from him. Mr. Spray, the singer of Christ’s Church happened to be there. After delighting his auditors with the superior skill with which he executed every piece he touched, he was asked by Sir John to play Plearaca na Ruarca. When he had finished and everyone had done paying him a well-merited compliment, what was the euloge of Mr. Spray? guess – “ ’t would just fit the Irish when Bonaparte would arrive amongst them,” and then began to sing it, pointing out the passage where it rises, as peculiarly formed for the ungrateful rebellious purpose. I don’t care said Sir John, it is a good tune and I’ll take it down from him.

The reader will naturally be surprised to hear of so great a musical amateur as Mr. Spray, treating the performance of the minstrel with such comtempt. But when we reflect that his noble British ancestors have made laws to deprive this order of man in Ireland , of their lives and properties, we can hardly be astonished that a remnant of their pure enlightened spirit should have descended to their offspring.

This political rant is useful for what it tells us, but we have to extract the facts from the opinion. We learn that “some time ago” Carr was in Dublin; the classical composer and arranger Sir John Stevenson wanted to take down airs from Carr, and so Stevenson requested Carr go to the house of Mr Doyle in Mountjoy Square. There were other people there. Carr played a number of pieces of music, and the people listened and praised his playing. Sir John Stevenson asked Carr to play “O’Rourke’s Noble Feast”. Mr Spray was inappropriately political and rude, and criticised the tune; Stevenson replied that it was a good tune and that he would make a transcription from Carr’s playing.

To me this is a fascinating account of live transcription from the playing of a traditional Irish harper. It is the only direct account I have seen that isn’t about Edward Bunting. Unfortunately, I don’t think we have Sir John Stevenson’s papers which might have contained his initial live transcription notation; I don’t even think we have his piano arrangement of this tune. But I wonder if any of his other piano arrangements, such as those in Moore’s Melodies, which might be derived from his live transcription from Carr’s playing?

Conclusion

William Carr is an interesting figure from the “lost generation” of harpers; he was just young enough to be at the Belfast meeting in 1792, and he lived through into the 19th century to find himself eking out a living playing every night in the Dublin taverns.

There are lots of gaps in our knowledge of his life story. We don’t know when he died – he was only 35 when the story about Stevenson was printed.

Many thanks to the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge for permission to reproduce the page from John Lee’s sketch book.

Fascinating stuff Simon. Thank you for this continuing enlightening work.

James Carr, Musician, is listed in the Belfast Street Directory of 1819 at 24 Mustard Street. I wonder if this is our man?

Fascinating. Thanks for posting

Thanks Catherine.