Since the early 19th century, with one or two gaps, a census has been taken every 10 years, to record the entire population of the United Kingdom. During the 19th century, Ireland, England, Wales and Scotland were all part of the UK, but they were administered differently. The first census in England, Scotland, and Wales was done in 1801, though at first only aggregate numbers of people were collected. The authorities in Ireland started a bit later; they tried to do a census in 1813, but apparently it was not completed. The first census in Ireland to be actually done was in 1821.

The Census was done on the ground by enumerators, who each travelled around an area recording details about who lived there. For most of the censuses this was done by delivering a form to every household, and then coming back a day or two later to collect the completed form. The forms were then collected together centrally, and all of these “returns” were analysed, and statistical analysis of the population was published. Then the full data of the returns was stored away in the national archives or record offices. Sometimes all the information on the household forms was hand-copied into big bound volumes which were put in the archive; other times the original household forms themselves were placed in the archive. Either way this full record of every individual was kept, but it was kept locked away for privacy reasons. After a certain amount of time, researchers were allowed access to these archived returns; nowadays the returns are published 100 years after the census was taken, and the archived documents are photographed and published online.

Over time the amount of information recorded on the census returns changed. At first, only the number of houses and residents was written down (1801), and there were not individual household forms. The Census of Ireland 1821 tried to list the name of every individual; it seems that this was not done in the rest of the UK until 1841. I get the impression that the Irish enumerators consistently collected more information than the British ones. The information recorded for every individual was their name, age, and occupation, organised by the place they were staying on census night. As time went on, other fields were added including place of birth, marital status, infirmities, language ability, etc. Not all fields were always filled out very correctly but in general it is a very useful data-set.

Because every individual was listed in the census returns, then, from 1821 all of the traditional harpers in Ireland would have had their names, ages, and occupations, and where they were staying on census night, written down into the original census returns.

Loss of the Irish census records

Unfortunately for us, almost none of the Irish census returns from the 19th century survive. The census returns for 1881 and 1891 were destroyed by the government in 1918, apparently to recycle the paper because of paper shortages, despite lobbying by the record office to preserve them.

The household forms for 1861 and 1871 were (I think as standard practice) destroyed by the government after the summary reports had been published. According to the Central Statistics Office, the English, Welsh, and Scottish returns for 1861 and 1871 had been first transcribed into bound volumes, and then the household forms were destroyed. In Ireland, they neglected to do the transcriptions before destroying the forms.

The Irish census returns for 1821 through to 1851 survived complete until 1922, when they were mostly destroyed in the fire at the record office at the Four Courts. The building had been occupied by the anti-treaty IRA at the very beginning of the Irish civil war; the Irish government used artillery guns to fire shells at the building, which caused the fire. My header photo (from the NLI) shows the Four Courts burning on 30 June 1922. The Public Record office is the part of the building to the left of the photo. There is more information about the destroyed Public Record Office at the ambtious Virtual Treasury online project, which aims to “re-imagine and reconstruct through digital technologies the Public Record Office of Ireland”. There is a page there about the lost census records.

This trail of destruction means that the census records are extremely unhelpful in finding information about the traditional Irish harpers during the 19th century. But I have managed to find some snippets of information about a few of the harpers. This blog post is to look at what we can discover.

Accessing the census records

The Irish census returns are all digitised and indexed freely online at the National Archives of Ireland. The images are considered copyright-free under the copyright status of Irish state documents. The search facility is pretty good, and it allows you to search by occupation. However there are no harpers to be found (except “linen harpers” who worked in the linen manufacturing industry).

The English, Welsh, and Scottish census returns are also digitised and available online; however they are copyrighted and are not freely available, but are licensed out by the UK National Archives to commercial companies. I have used the Ancestry online index which allows searching for free but you have to pay for a monthly or annual subscription to see any results or to browse the original census returns. The search facility is difficult to use. They only have the English and Welsh census return images; the Scottish ones are licenced through a different company which I have not yet looked at. There is also an ongoing free open source project called Freecen which uses volunteers to transcribe the English, Welsh and Scottish census returns. The database is then searchable; you can search by occupation but only combined with a name and place, and I am not sure it works that well. There are a lot of gaps still which are being slowly filled by the volunteer transcribers. This project does not give access to the original return images.

In summary, the 19th century English, Welsh, and Scottish census records are very complete but difficult and/or expensive to search and view. The 19th century Irish census records are extremely easy and free to search and view but only a few fragments survive from before 1901.

Harpers in the 1901 census

The census was taken on 31 March 1901. The Irish census returns survive pretty much complete, and I have found three of the four traditional Irish harpers who were still alive in 1901. For each of these three we are given the place where they lived, their names, relation to head of family, religion, whether they can read and/or write, their age, sex, occupation, marital status, where they were born, whether they had the Irish language, and if they were deaf, dumb, blind, or “imbecile idiot or lunatic”. We also get the same information for all the other people living at the same address. This is all very useful information.

Click on the image to go straight to the online index entry, which includes the page image(s). I think these are the actual household forms, filled in at home by the head of each household.

The first form, for George Jackson, shows him in Clifton House which is a kind of old people’s retirement home; the stack of forms listing all of the residents would have been filled in by some kind of secretary or manager of the home.

Paul Smith’s form was presumably filled in by his wife Anne or another relative.

Peter Dowdall most likely filled in this form for his whole family:

I have included two of these in their pages when I wrote them up; George Jackson and Paul Smith. The third is Peter Dowdall who I have not yet written up.

One of the things I notice is that under “occupation” none of these give “harper”. This is because Paul Smith was retired; he puts “no occupation”. And the other two never worked as professional harpers; George Jackson worked as a clockmaker and Peter Dowdall was a clerk.

You’ll notice that none of these three had the Irish language. This is not surprising given what we know about the history of the language through the 19th century. See Aidan Doyle, A History of the Irish Language (OUP 2015) for more on this.

There was a fourth traditional harper still alive in 1901, who is presumably in the census, but I don’t know his name and so it is impossible to find him.

Harpers in the 1891 census

The census was taken on 5 Apr 1891. The 1891 Irish census returns were utterly destroyed and nothing survives, only the statistical summary. So we have no hope of finding census records of these harpers who were still alive in Ireland.

However if you check my timeline of traditional harpers, you’ll see that Roger Begley in England was still alive in 1891, and so we can find him in the English census. I have added a comment to the bottom of my post about him. He is in Dewsbury Workhouse. This is not the household form I don’t think; this is the bound volume where all the information from the household forms has been copied. The entry reads:

Name | Relation | Marital status | Age | Occupation | Where born

Roger Begley | do | Widower | 60 | Music Harpist | Ireland

Under “Relation to head of family, or position in the institution”, the first person on this page is listed as “Pauper Inmate”; everyone else including Begley has “do” (for ditto, i.e. the same as the previous person).

There are also columns for employment status, which are left blank for everyone in the workhouse, and for “if (1) Deaf-and-dumb (2) Blind (3) Lunatic Imbecile or idiot”. This last column is left blank for Begley, which is interesting because we have other information that he was blind.

Harpers in the 1881 census

The census was taken on 3 Apr 1881. Again, Ireland is a dead loss because of the total destruction of the 1881 census returns. This is a great shame because it would be great to be able to find Patrick Murney, Hugh O’Hagan, and Samuel Patrick in the census returns. But they are all lost forever.

Meanwhile in England, we can again find Roger Begley. On 3 Apr 1881, he was in a house in Bright Street, Dewsbury. Again this is the transcribed copy of the return in the bound volume; you can tell that because the page has a whole series of houses entered one after the other. The entry for Roger Begley’s household reads:

Name | Relation | Marital status | Age | Occupation | Where born | if…

Roger Bagley | Head | Widow | 47 | Musician Harpist | Belfast Ireland | Blind

Kate do | Daug | | 13 | Scholar | Bradford Yorkshire |

I should add that there is not a column for “sex”, but there are two columns for age, one for males and one for females, and so the person’s sex is indicated by which column the age is put in. I discuss his daughter Kate in my post about him.

Harpers in the 1871 census

The census was taken on 2 Apr 1871. Once again, the harpers in Ireland are a dead loss because we don’t have the records. If only we could see the entries for Billy Griffith, Sally Moore and Tom Hardy, we could learn so much about them because we know so little about them.

But once again we can find Roger Begley in England. He is in Dewsbury, in a house in Westgate. The entry reads:

Name | Relation | Marital status | Age | Occupation | Where born | whether…

Rodge Begley | Head | Marr | 3[6] | Harpist | Belfast | Blind from small pox

Hannah | Wife | .| 34 | Hawker | Dublin |

Kate | Dau | Um | 3 | | Bradford |

Harpers in the 1861 census

The census was taken on 7 Apr 1861. I am not finding any harpers at all in any of the surviving census returns. Roger Begley had not moved to England by then (though I don’t know where he was).

While the Irish census returns for 1861 have been utterly destroyed and lost, there is a nice surprise for us in the summary, published in 1864. I realised this after reading an article by Karol Mullaney-Dignam (‘Music masters and musicianers: census records and Irish music history, 1821-1911″, in Irish Musical Studies 12: Documents of Irish music history in the long nineteenth century eds. Kerry Houston, Maria McHale and Michael Murphy, Four Courts Press, 2019). She explains how these published statistical tables give breakdowns of ages and locations and sexes by occupation; and she discusses the different categories of musicians and music teachers.

In 1861, unlike the years before and after, the published statistical summary analyses and tabulates a lot more information on occupations. In the other analyses before and after, everything is categorised into standard categories, and so we only see the statistics for musicians and music teachers. But the 1861 analysis seems to use whatever free-entry self declared occupation the individuals said on the (lost) returns. And so, under the heading of “ministering to amusement”, we find 31 organ builders, 1 harpmaker, 10 organ grinders, 1 theatrical costume maker, 3 ventriloquists, 2 professional cricketers, 13 billiard table makers, 1264 “musicians (unspecified)”, and thirty other diverse categories, and last of all 5 “Irish harpers”.

The published statistical analysis includes four tables. Every table has triple columns for counting men and women separately as well as in total; all five of our harpers are men. Two of the tables show the ages of the harpers (presenting the same data but organised differently); on pages lxiv-lxv and pages 494-5.

| Ages | 25-29 | 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-44 |

| Number of Irish harpers | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

Another table divides our five harpers by province, on page 474:

| Province | Leinster | Ulster |

| Number of Irish harpers | 1 | 4 |

| fiddlers | 54 | 94 |

| pipers | 40 | 11 |

I am trying to stay focussed but I could not help a little digression. There is a large amount of further statistical analysis that we could do here, comparing the harpers to other musicians, both traditional and classical. I think I was struck by the obvious regional differences in the proportions of harpers. There are a lot more classical musicians in Leinster, because of the scene in Dublin I suppose; but in my little table above I have added the numbers for fiddlers and pipers because these are likely traditional musicians and more comparable to the harpers. We can see that there are more fiddlers in Ulster than in Leinster, but not by as big a ratio as harpers. And we see that there are almost four times more pipers in Leinster than in Ulster. The population of Ulster was about 30% bigger than the population of Leinster in 1861 (page x). Anyway that’s the end of my wee digression.

The final published table from the 1861 statistical summary, on page 510, divides our five harpers by religion. “Established Church” is the Church of Ireland; there are many other columns for Presbyterians, Methodists, etc.

| Religion | Established Church | Roman Catholics |

| Number of Irish harpers | 2 | 3 |

Karol Mullaney-Dignam prints all these figures in her article (p190). But I thought we could try to analyse what we now know about the Irish harpers alive in 1861, to see if we can work out who these people might be.

I went to my timeline and tried to extract a list of traditional Irish harpers in 1861, with their ages, religion, and where I think they were on 7th April 1861.

| Name | Age | Place | Religion |

| Thomas Hardy | late 20s? | Presumably Belfast (Ulster) | Apparently Protestant (CoI or Presbyterian) |

| Sally Moore | perhaps 29 | Presumably Belfast (Ulster) | Unknown |

| Roger Begley | Late 20s | Away from Belfast, place unknown | Unknown |

| William Griffith | perhaps early 30s | Presumably Drogheda or Dublin (Leinster) | Presumably Catholic |

| Paul Smith | 37-39 | Presumably Dublin (Leinster) | Church of Ireland |

| Hugh O’Hagan | 39 | Perhaps Dundalk (Leinster, near Ulster border) | Presumably Catholic |

| Patrick Murney | Apparently late 30s, perhaps 40 | Presumably Belfast (Ulster) | Presumably Catholic |

| Samuel Patrick | I think 42 | Somewhere in the South (Leinster or Munster) | Apparently Protestant (CoI or Presbyterian) |

| Joseph Craven | 45 | Presumably Dublin (Leinster) | Unknown |

| Andrew Bell | 46 | Touring Ulster | Family appears to be Church of Ireland |

| Hugh Frazer | 53 | perhaps Drogheda or Dublin (Leinster) | Presumably Catholic |

| Thomas Hanna | 58 | Presumably at Castle Forbes (Leinster) | Unknown |

| Patrick Byrne | early or mid 60s | in Dublin (Leinster) | Protestant (presume Church of Ireland) |

We can make up our own census statistics tables based on this information, for these 13 harpers we know about on my timeline, 12 men and 1 woman.

| Age | 25 – 29 | 30 – 34 | 35 – 39 | 40 – 44 | 45 – 49 | 50 – 54 | 55 – 59 | 60 – 64 |

| No. | 3 | 1 | 2 or 3 | 1 or 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Province | Leinster | Ulster |

| No. of harpers | from 6 to 9 | 4 or 5 |

| Religion | Protestant | Catholic |

| No. of harpers | 5 (plus up to 4 unknown) | 4 (plus up to 4 unknown) |

The first thing that we can see is that there are more harpers that we know about in 1861, than there are in the census. Presumably this is simply because over half of the harpers in 1861 declared their occupation as “musician” for example. But we can also see that the demographics of the harpers we know about is somewhat different from the harpers recorded in the 1861 census.

We have a lot more harpers who we are guessing are in Leinster. I think there are two possible answers for this; one might be that declaring yourself an “Irish harper” might be a more Ulster thing; another might be that some of our harpers normally based around north Leinster may in fact have been touring in Ulster in April 1861, without leaving us any records of this. For most of these harpers we don’t have the fine-grained details of their movements to be able to say. The only one who I would be really confident about their location is Patrick Byrne, who was staying at 2 Leinster Street, Dublin for the first half of April 1861.

We also can see that we know about a lot more older harpers than are represented in the 1861 census statistics. Again I wonder if it is a younger person’s thing to declare your occupation as “Irish harper”, and if the older men were more likely to declare as “musician”?

I am so much less certain about the religious affiliation of the harpers that I don’t think we can usefully compare these statistics.

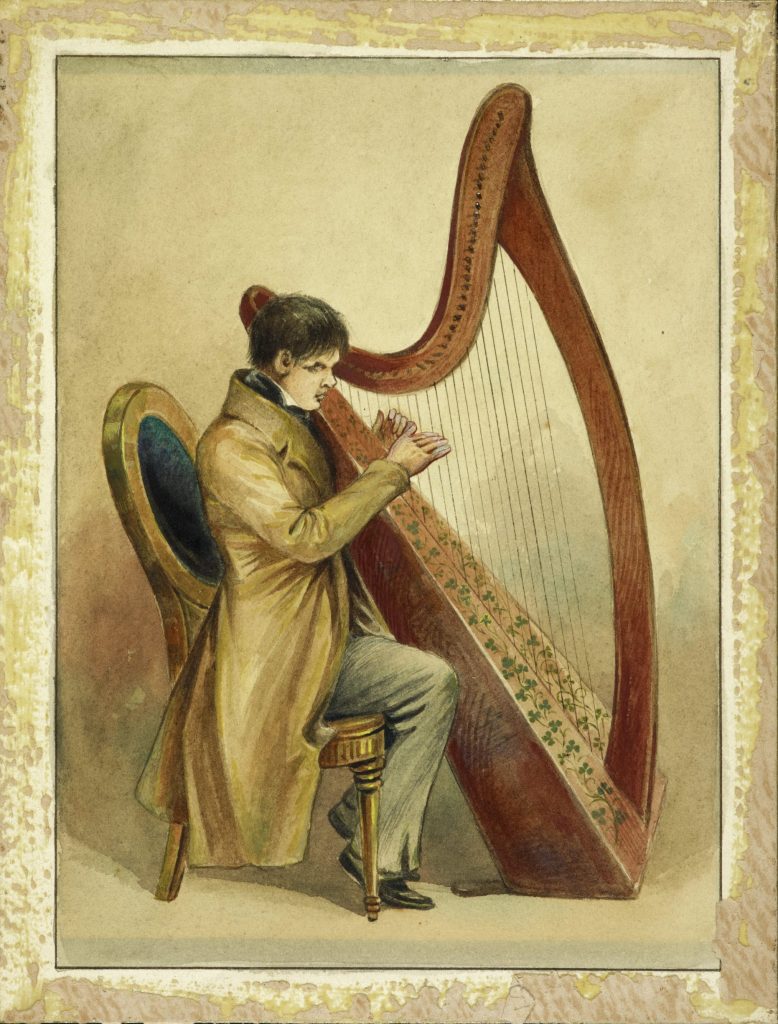

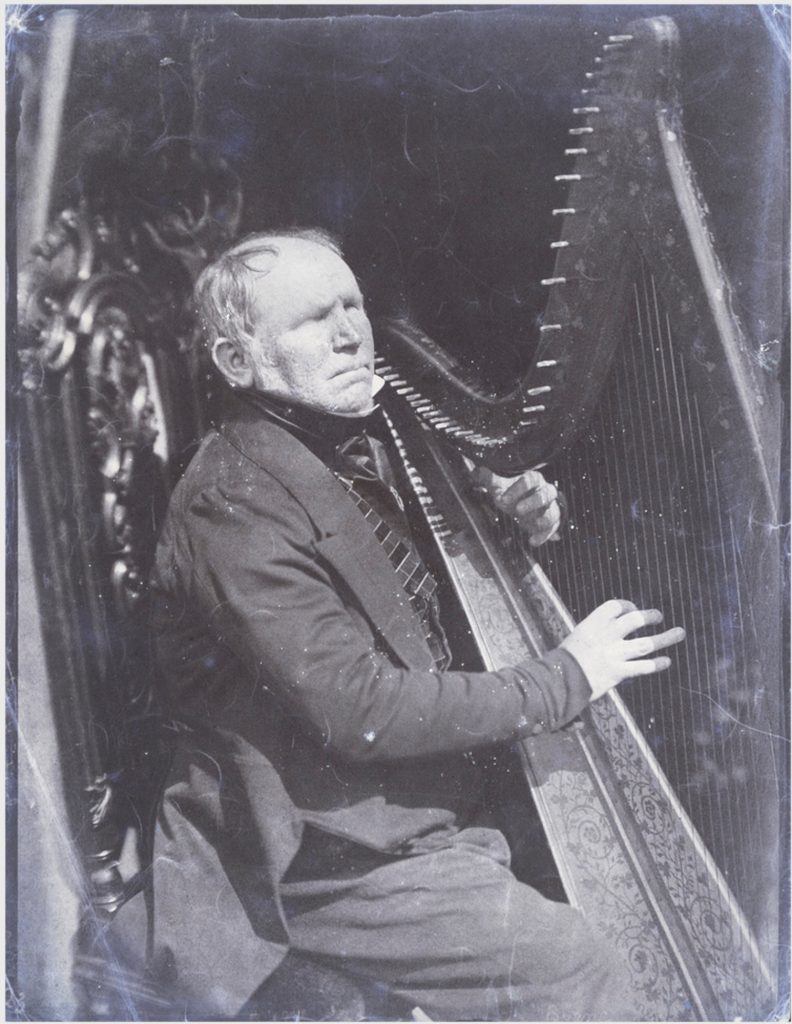

BELUM.P328.1927. Image used Courtesy of National Museums NI.

Can we try to pin down some of these floating numbers? Who are the five harpers in the census? We can quickly rule out some of them; Sally Moore is obviously not one of the five men. And Craven, Bell, Hanna, Frazer and Byrne are older than the five who are in the census summary. But it is harder to suggest who the five men may have been. Tom Hardy may be the youngest one; William Griffiths is the only one I know about in his age bracket; Paul Smith could be one; if Hugh O’Hagan was working in Ulster on 7 Apr 1861 he could be one, and if Pat Murney was 40 rather than late 30s in age he could be one (I don’t know his actual year of birth). That would fit with our statistics I think for ages, places, and religion. But this is just a guess.

Harpers in the 1851 census

We can’t do the analysis above for 1851, because the published census statistics gather all musicians under a general heading of “musicians” and “music teachers”.

The 1851 Irish census returns were destroyed in the Four Courts fire in 1922. A few returns survive, mostly from County Antrim. But I have not found any harpers in these returns.

However, John Scully (Ah How D’you Do Sir, Carrickmacross 2024, p.77) found the Irish harper Patrick Byrne in the English census of 1851. This was one of my motivations to get access to the English census returns.

Byrne is listed because he was staying with his patron Earl Ferrers at Chartley Castle in Staffordshire. I have not yet written up this period of Byrne’s life; you can read about an earlier visit to Chartley in 1846, in Patrick Byrne part 6.

The entry has 20 people staying at Chartley Castle on 30th March 1851. After Washington Shirley and his wife, and their son and daughter, all the servants are listed. There may be a ranking issue going on; the first servant is Thomas Leadbetter the butler; next is Thomas Hewlett the valet; third in order is Patrick Byrne. After him comes Jane Smith the housekeeper and ladies maid, and then all the others continuing on to the next page.

Patrick Byrne’s line reads:

Name | relation | Marital status | Age | Occupation | Where born | Whether…

Patrick Byrne | Harper | U | 51 | Irish Harper | Ireland | Blind

This is a fascinating snapshot into the household where Byrne is staying but it also gives us the youngest age for him I have yet seen; this would suggest his year of birth was 1799-1800, but all the other records of his age would make his birth some time between 1794 and 1798. I think the conclusion there is that we just don’t trust the ages given in the census returns or indeed in any other official record.

Harpers in the 1841 census

The 1841 Irish census returns were lost in the 1922 fire, and only a very few fragments survive. I have not found any harpers in any of the surviving fragments. We can see from my timeline that there were at least 20 harpers working in Ireland in 1841, plus at least 10 more young people who had not yet started learning the traditional wire-strung Irish harp. If only we had this data we could find out a lot more about the tradition.

However we can find the traditional Irish harper Abraham Wilkinson listed in the Welsh census. He is in Treborth, between Bangor and Caernarfon, North Wales. This is a great insight into his movements, since we know he played a concert in Caernarfon in September 1840. Now we see him six months later still in the area, and potentially connected to the wealthy Irish widow Sarah Drew who was living in the next house in Treborth.

Here is Abraham Wilkinson’s entry. He is the only occupant of his house on the 6th June 1841:

Name | Age | Profession | Where born

Abraham Wilkinson | 42 | Harper | I[reland]

You can see we have a lot less information in this earlier return. But it gives us a great insight into his life and movements. I have written up this census entry as a comment on my post about him.

Harpers in the 1831 census

The 1831 census of Ireland only recorded the heads of households, and the number of males and females in each of their houses, so would be much less useful to us anyway, but almost all of it was destroyed in the 1922 fire and only fragments remain.

The census of England and Wales was apparently even more minimalist, with just headcounts of each area and no names recorded.

Harpers in the 1821 census

The Irish census was taken on 28 May 1821, and recorded name, age, occupation, relationship, and size of house and land. It tried to list every individual and so it would be of great use to use except that almost all of it was destroyed in the 1922 fire. Only fragments remain from a few counties.

I have not found a harper in the fragmentary 1821 Irish returns but I did find one of Patrick Byrne’s patrons, Mary Kellett listed which helped me understand his description of his visit there. But I am not really looking for the patrons – I am sure we could find a lot more of the harpers’ patrons in these census returns if we wanted to. But I am too busy chasing the harpers. My timeline lists around 10 harpers active in 1821, plus another eight or so who may or may not have still been alive by then, plus about six young students studying traditional wire-strung Irish harp under Edward McBride in the Cromac Street harp school.

Because a significant part of the fragmentary returns are from county Cavan, I did look for Bridget O’Reilly. However there are 419 women called Bridget Reilly in these fragments from Co Cavan and I don’t see one that is plausibly her.

Overseas

This post is only considering the British and Irish census records. I think there is scope for trying to find harpers in the US and Canadian census records. We know Matthew Wall was based in Canada in about 1830, and in the USA from about 1832 through to his death in 1876, and we have some information about his family and places, so we may be able to find him in the 1831 Canadian census, or the 1840, 1850, 1860 or 1870 US censuses. But I have not even started working out how to access these.

Other harpers may have gone to America in the 1840s; we have information about the Irish harpers Mr. Rennie and Mr. O’Connor planning to emigrate in 1847. But we don’t have either of their first names, so I don’t see how we could sensibly look for them in the US censuses without finding more information first.

Conclusion

The census returns are very frustrating because we only find a very few harpers listed in them. But I love that when we do find a harper, we get a sudden snapshot of where they are, the household they are in, and little snippets about their age or whatever. For many of the harpers we have so few records, that a census entry would become a huge piece of the evidence. For example, for Abraham Wilkinson I only had one line from the minute book recording his entry into harp school, and two news clippings about one concert he played in; and so finding him in the census was a big increase in the information we have about him.

I also think we are very unlikely to find a previously unknown harper in the census returns. I think we have to already know a harper’s name and a bit about them before we have any hope of finding them in the census.

Really though, other sources are more useful. The marriage and death records can be useful if I can find a harper in them, but many of the harpers are just that bit too early to appear in these records. Births, marriages and deaths started being recorded by the government in 1837 in England and Wales, and in Scotland from 1855, while in Ireland non-Catholic marriages were recorded from 1845, and all other marriages, and births and deaths, from 1864. And again we have to know the person’s name and a bit about them before we can try to find them in the marriage or death records.

I think the old newspapers have been the most useful source of information about the traditional harpers. Perhaps I should write a similar post about Irish harpers in the 19th century newspapers.

One thought on “Irish harpers in the census records”