I think that Joseph Craven was a traditional Irish harper, though actually I have no information about his background or musical lineage – it is possible he was a classical pedal harpist. But I think he is more likely to have been one of our traditional boys. In this post, we will go through what we do know about him and see what we think. If new material appears to prove me wrong, we can put it in the comments at the bottom.

Joseph Craven’s obituary is our main source of information.

DEATH OF AN OLD IRISH HARPER

Irish Times, Wed 8 Sep 1869 p2

Mr Joseph Craven, the celebrated old Irish harper, who has for the last twenty years been performing in the Ship Hotel, died yesterday afternoon in St Vincent’s Hospital. He possessed a genuine old harp of this country, and though blind could perform the most difficult airs with artistic precision. During his lifetime he played before O’Connell at the great demonstration in Dublin, and he also took a prominent part at McManus’s funeral. He leaves a wife and family unprovided for, and we are happy to say a subscription has been set on foot for those he leaves behind.

We will take each episode in turn and see what we can find out about him then. Hopefully in time more information will appear, helping us to say more about Craven.

Birth and Education

Joseph Craven’s death record says he was aged 53 in September 1869. If we believe the age on the death record, we can calculate that he was born in 1815 or 1816.

We have no information about his upbringing and musical education. The obituary says he was blind; it seems possible that he was admitted to the Irish Harp Society school in Belfast perhaps in the late 1820s or early 1830s, when he would have been aged in his teens. We have the lists of students at the school for 1820, 1821, 1824, and 1826, but after that the fragmentary surviving records of the Irish Harp Society only name two pupils from between 1826 and the closure of the school in 1839-40. If we guess that perhaps two boys were admitted each year, that would mean there could be something like 30 pupils who we aren’t told the names of.

If Craven did attend the Irish Harp Society school in Belfast, he would have studied under the master Valentine Rainey, probably boarding at the Harp Society house and studying full-time to learn the traditional playing techniques and music of the traditional wire-strung Irish harp. On the completion of his study, he would have been presented with a harp by the Society, as well as a certificate of ability and good conduct. The Obituary says “He possessed a genuine old harp of this country” which may refer to one of the floor-standing 37-string wire-strung Irish harps that were made for the Society by John Egan.

But I think it is also worth pointing out that this is just speculation. We know there were other people working in Dublin in the 19th century, advertised as “Irish harpers”, who played classical pedal harp and who had been taught by British or European classical pedal harp teachers. So at the moment we can’t rule out that Craven may not have been a traditional harper, but may have been a classically-trained pedal harpist. But I think that is less likely, partly because of him being blind.

O’Connell demonstration

During his lifetime he played before O’Connell at the great demonstration in Dublin…

Irish Times, Wed 8 Sep 1869 p2

The story of Daniel O’Connell (“The Liberator”) and his political and popular campaigns to “repeal” the acts of Union between Great Britain and Ireland, is long and complex. There are many interesting threads that parallel the story of our harpers through the 19th century. But the direct connection is O’Connell’s use of traditional harpers in his processions and parades.

O’Connell seems to have been a master of political theatre and symbolism. As part of this, he often included one or more costumed harpers in his lavish and spectacular processions from 1832 through to 1845

In 1843 and 1845, O’Connell organised a series of over fifty “monster meetings” all across the south and middle of Ireland (see Gary Owens’s article in History Ireland vol 2 no 1 Spring 1994 for a good overview). There were at least two of these grand theatrical processions through Dublin. The processions were generally led by trades guilds, and temperance bands. Then there would be dignitaries and then O’Connell himself standing on a kind of triumphal car, and then the mass of people following, in a kind of moving theatrical display of radical Irish society. They would process to a meeting ground where O’Connell would give rousing political speeches.

It seems that the attendants on O’Connell’s car would usually include a costumed harper playing a harp. We have quite a few descriptions of the car which mention the harper, in published descriptions of processions in different places around Ireland, but we are usually not told the name of the harper.

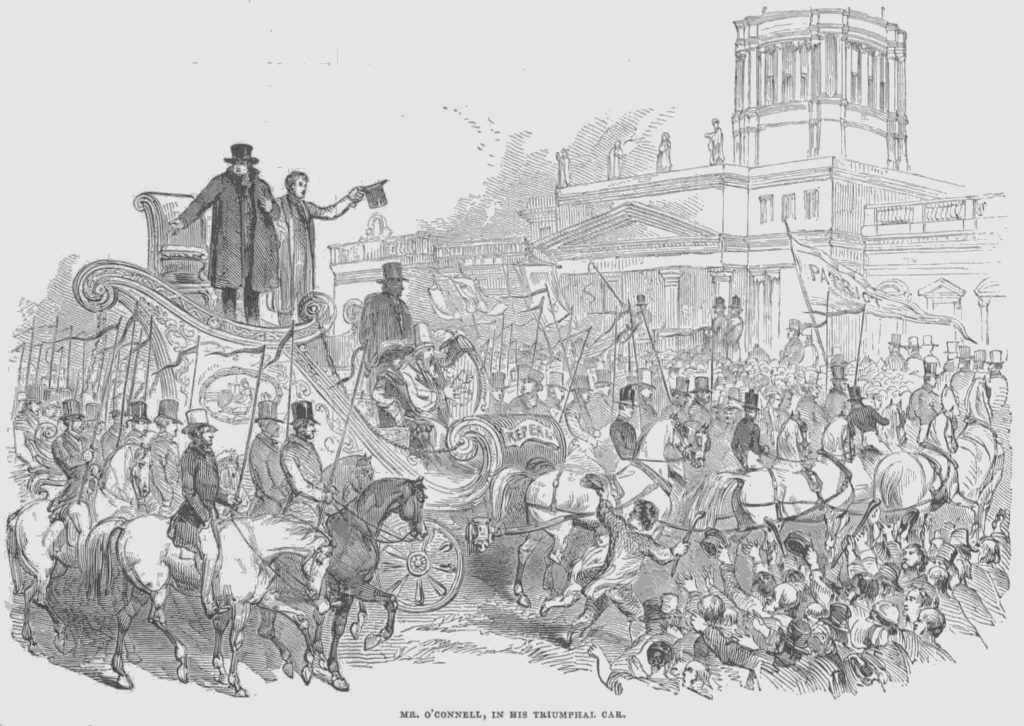

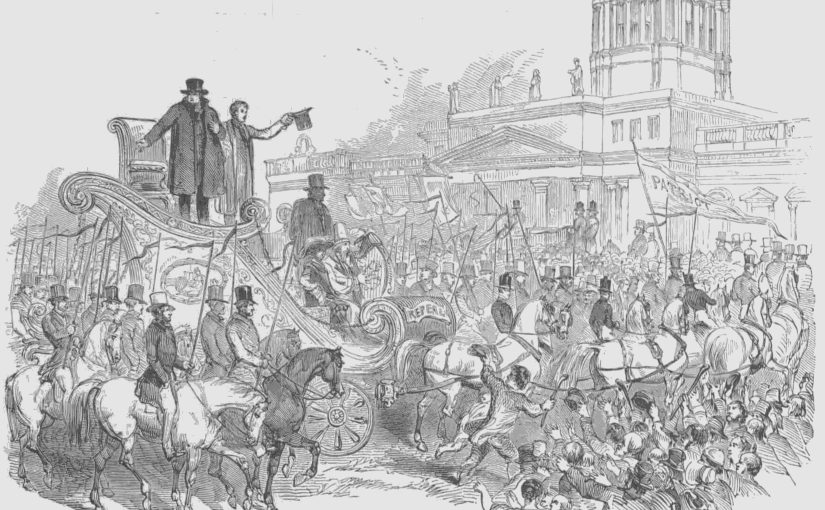

We have very atmospheric drawings and a description of a parade held in Dublin, I think on 7th September 1844, after O’Connell was released from a brief spell in prison. The un-named harper is visible in both drawings, seated at the front of the carriage.

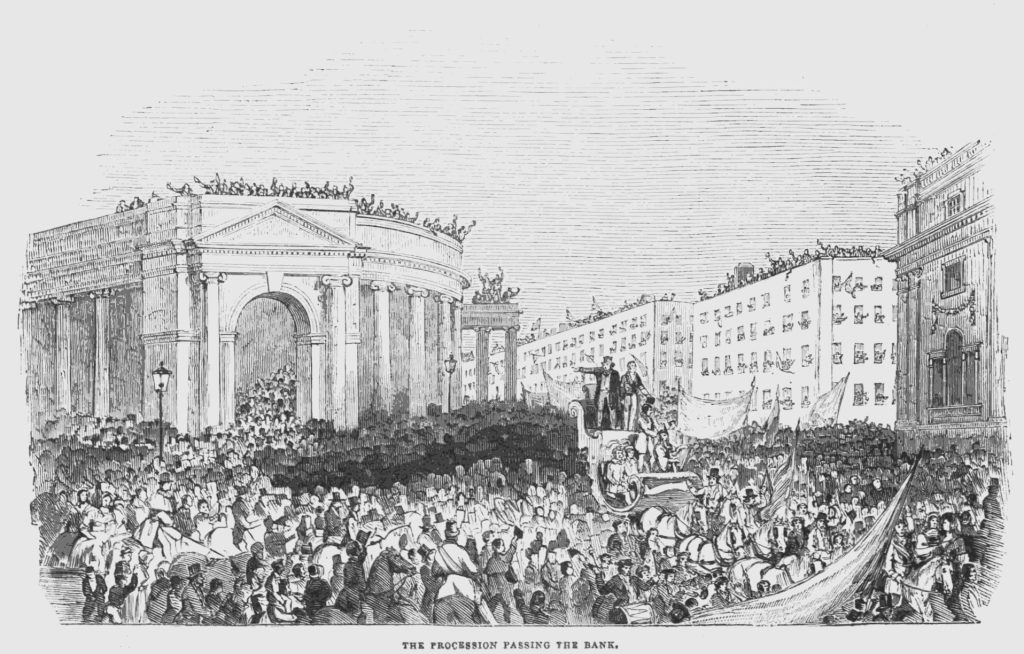

I think this illustration above is a kind of imaginary view of the procession, with the Custom House in the background (you can only really get this view of the Custom House from in the middle of the river!)

On the previous page of the newspaper is the other illustration (below), which shows the procession heading past the front of Trinity College in College Green.

I think this must be the “third illustration” described in the article text:

The third illustration shows the triumphal chariot on its progress to Merrion-square. It was surrounded by a crowd so dense, that it was with great difficulty the six splendid dappled grays could force the cumbrous vehicle along. This vast vehicle originally figured so far back as 1832, at the chairing of Mr. O’Connell in that year. It is apparently constituted of a large platform, bearing three stories, arranged like steps of stairs, and profusely decorated with purple velvet, gold fringes, gilt-headed rails, bosses, and paintings. On the top stair were two large arm-chairs, covered with purple velvet and gilding in (or rather standing before) which were placed Mr. O’Connell and his son John. The honourable gentleman stood up to his full height, with his head slightly thrown back, and waved his velvet cap and bowed incessantly, whilst at intervals his lips were seen to move. On the second stair was seated the Rev. Dr. Miley, and on the lowest range sat Mr. D. O’Connell, junior; an Irish harper attired in the full dress of the days “when Malachi wore the collar of gold” uselessly playing on a genuine Irish harp, and two young gentlemen (who we understand were Mr. O’Connell’s grandsons) dressed in tunics of green velvet with caps of the same material and white feathers…

Illustrated London News Saturday 14 Sept 1844 p165

We can’t know for sure if Joseph Craven was the harper in these pictures. It could have been another different harper. But we are told that Craven played in at least one Dublin procession like this. And anyway I think most of O’Connell’s processions would have looked very similar to the one shown in these pictures.

Performing in and around Dublin

It seems to me that Craven’s usual work was playing daily in hotels. Many of the 19th century Irish harpers seem to have made a living this way. We have adverts from the Autumn of 1845 which sets the scene:

THE DUBLIN HOTEL AND TAVERN.

Freeman’s Journal, monday 1 Sep 1845 p1

112, MARLBOROUGH-STREET,

MICHAEL JOHNSTON, PROPRIETOR,

(LATE OF P. DONOHOE’S, ABBEY-STREET)

M. J. returns his grateful thanks to to his generous Friends for a continued preference to his house, which will be always supplied with the best materials the Markets can afford.

Hot Joints Every Day from Five to Seven o’Clock at One Shilling per head for Dinner; Punch 4d. per tumbler. Malt of all descriptions in proportion.

M. J. begs leave to state that in addition to his Dining-rooms he has opened a spacious Coffee Room, and begs to say he has engaged the celebrated Irish Harpist, Mr. JOSEPH CRAVEN, who will play nightly from Seven to Twelve o’Clock.

The Hotel Department will be conducted with every possible care and attention.

Arrived this day a Cargo of the celebrated Pooldoody Oysters.

This advert was reprinted on the following day, and again on 7th October with the name mis-spelled “Cravens”. I think that the Hotel was on the site of the present day no. 112. The Street Directory of 1840 lists this site as 109 so the buildings must have been re-numbered between 1840 and 1845. This block seems to have been completely destroyed by the British artillery fire in 1916.

Joseph Craven also seems to have tried his hand at performing on stage. At least, I am assuming this may be him with his name mis-spelled in the publicity.

ASSEMBLY-ROOMS KINGSTOWN.

Freeman’s Journal, Monday 7 April 1851 p1

FOR ONE NIGHT ONLY

Which will be tastefully fitted out with appropriate Scenery.

Select accommodation for the Respectable Families of the neighbourhood, who are respectfully informed, that

VALENTINE VAUX,

THE

DRAMATIC VENTRILOQUIST, MIMIC, AND DIALOGIST,

Will appear thereat in One of his Ventriloquial and Merry-making Entertainments,

ON THIS EVENING.

On which occasion he will introduce his Drawing-room Amusements, and in the Laughable Play of

MASTER AND MAN,

rapidly assume all his Comic Characters, exhibiting in a variety of Tests and Histrionic Displays of Ventriloquism, the wonderful and amusing powers of the human voice.

Craken, the inimitable Irish Harper is engaged for the Evening.

First Class Seats, 1s. 6d.; Second Class, 1s.; Children half-price.

Doors open at half-past Seven, to commence at Eight, and to conclude at Ten o’Clock.

Kingstown is the 19th century name for Dún Laoghaire. I am not sure where the old Assembly Rooms were. We can’t really say anything about our headline act here except that he is borrowing his name, Valentine Vaux, from a parody novel that was published in 1840.

Craven also seems to have diversified into providing musical illustrations for “interesting” lectures (assuming this is him again with his name spelled wrong).

LECTURES IN DUBLIN

Dublin Weekly Nation, Saturday 18 December 1858 p4

On Monday evening Mr. O’Brennan delivered an interesting lecture in the Theatre of the Mechanic’s Institute. The subject was the bards, the harp, and primitive music of Ireland. There was a crowded and respectable audience. The lecturer as a prelude to his subject made a few remarks regarding the primitiveness, gracefulness, and musical aptitude of his native tongue. In connexion with the subject of his lecture, he gave several instances of Greek words as being essentially Iranian or Irish. The able lecturer observed that as regards the word Irish there was some mistake. The origin of the word is to be found in the language itself. At a very early period from the mountains west of Hindostan to the Levant was called both Persia and Iran, which ‘signifies Sacred Land,’ and as a colony thence came to this western isle the first settlers gave it the appropriate name Irin, which ‘signifies Sacred Island,’ Iran is made up of two Celtic words, ‘Ir,’ Sacred and ‘an’ Land; so called because God created man, and held such frequent intercourse with him in Western Asia. Mr. O’Brennan further stated that primitive Scythia, according to the best Greek geographers, was a part of ‘Iran,’ that in their travels towards Spain, they imported some of their own enlightenment to Greece, Egypt, and Eritruria, and called our country ‘Irin,’ Sacred Land, because of its insular position. Their original country being called ‘Iran,’ they very naturally called Ireland after their own country, with a difference that the one was a land and the other an Island. Even their very words are the roots of the Greek ones. The Pelasgic – a dialect of the Celtic (the lecturer remarked) was unquestionably the basis of Homer’s poetry, and indeed of the Greek language. Here Mr. Brennan drew the attention of the audience to the beautiful Irish melodies of the Arch-bishop of Tuam, explaining their measures and their sweet modulations. To illustrate his statement Mr Creaven, the celebrated Irish harper, and amateur Irish singers, natives of Dublin, and members of the Irish class, 48 Middle Abbey street, were introduced. Their appearance was greeted with enthusiastic cheering. The melodies in the Irish tongue, with harp accompaniment, thrilled the hearts of the audience. Several brilliant airs were played by the harper, and at the conclusion a short history of the antiquity of the harp was given, but the lecturer stated that his subject was such as would require a series of six lectures.

I think that an entire PhD thesis could be written about Mr. Brennan and his linguistic theories, but we will ignore that because (perhaps like the cheering audience) we are only here for the music. The description of the performers is not too easy to parse, but I am reading it as saying that there was Mr Craven the harper, and there was also a group of amateur Irish singers who were natives of Dublin and members of an Irish language class. The article seems to describe the singers singing Thomas Moore songs as Gaeilge while Craven played the harp to accompany them. Craven also played some instrumental airs.

It is an interesting research question as to how many of the 19th century harpers spoke Irish. I think that the majority of the 18th century Irish harpers spoke Irish. However, the language was in rapid retreat through the 19th century (see Aidan Doyle, A history of the Irish Language, OUP 2015 for a good general overview). We have the statement that Miss O’Reilly was the last to learn the harp in the old tradition through the medium of the Irish language; I discussed this on my post about Bridget O’Reilly. For the three traditional harpers I know of who were alive in Ireland in 1901 we have their census returns, which indicate none of them had Irish. I have added a column to my big list of 19th century harpers, to record information one way or the other, but for most of them (like Craven) we can’t say at the moment.

McManus funeral

…and he also took a prominent part at McManus’s funeral.

Irish Times, Wed 8 Sep 1869 p2

Terence McManus’s funeral was a great political spectacular, held in Dublin on Sunday 10th November 1861. We have a number of descriptions of the harper in the procession from Dún Laoghaire to the Mechanics Institute in Dublin (where the Abbey Theatre is now), where it picked up the body, and continued on to Glasnevin Cemetery. It seems that Craven was attempting to reprise his role as the symbolic harper seated on O’Connell’s carriage, but it also seems that his presence at the funeral was less inspiring and more ridiculous than back in O’Connell’s day. On the other hand the disrespectful descriptions and the laughter from the crowd may reflect more on the charged political symbolism than on the actual appearance of Craven.

M’MANUS’S FUNERAL

Irish Times, Monday 11 November 1861 p4

This being the day appointed for conveying the remains of M’Manus from the Mechanic’s Institute, Dublin, to Glasnevin Cemetery, a considerable number of people, anxious to see the procession, left Kingstown by the train and omnibuses, at an early hour. Later in the day about one hundred and forty men and boys, seated on twenty-one cars, formed in procession in the least aristocratic part of the town, and in such order passed through several of the streets and thoroughfares, previous to starting on their tour to Dublin. The procession had one feature worthy of notice, irrespective of the crape tied upon every arm, for in the line was a large spring van, over which was placed a carpet, and in the centre of it stood a chair, which was well filled by a very corpulent, elderly, blind man, supported on each side by young lads, who performed on the Irish harp several national airs with as much spirit and energy as, considering the intense cold of the day, and the waggling of the conveyance, he could have been expected to display. So the procession moved on to Monkstown, but here the bard became silent, the frost seemed to overcome his patriotism, and the poor old man descended from his elevated position, and gladly exchanged it for the inside of of a cab which was passing at the time. As far as Kingstown is concerned, everything passed off orderly and quietly

I think the last line is a reference to some trouble and disorder that happened later in the day. I am also not sure about the cab episode, since we also have descriptions (below) of what seem like later stages of the procession. Monkstown is only about 1/8 of the way from Kingstown into the centre. Perhaps Craven took the cab into the city and re-joined the procession later, rather than having to ride and play for the entire 10km route from Monkstown in to the Mechanic’s Institute.

This is the second time we have found Craven in Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire). Was he perhaps living there for a while, or did he have personal or family connections there?

The organisation of the events seems reminiscent of the O’Connell processions, with a group parading in to town, and then the coffin containing McManus’s body joining the procession, and being taken out to the cemetery for the final burial.

Other reports give us different snippets of detail about Craven’s costume and appearance:

KINGSTOWN AND THE M’MANUS OBSEQUIES. – This day at 11 a.m. a long file of cars left Kingstown filled with passengers for the M’Manus funeral, and headed by a kind of van, on which was seated a “lay figure” dressed in what appeared to be a blanket, having an Irish harp on an elevated stand before him. The procession, before starting for Dublin, paraded around the principal roads and streets.

Dublin Daily Express, Monday 11 November 1861 p3

(From the Times)

Saunders’s News-Letter, Wed 13 Nov 1861

The obsequies of Terence Bellew M’Manus were celebrated on Sunday, and were “a great success.” All the celebrities of sedition were there. There were the Rev. Mr. Kenyon, P.P. of Templederry, and Mr. John Martin, a convict Irish patriot of 1848. There were Mr. Smith O’Brien and The O’Donoghue, M.P. In fact, the genius and virtue of Ireland was not to be deterred by the frown of the Church or the inclemency of the weather from rendering homage to a martyred enemy of the Saxon. Priests disregarded the advice of their Bishops, and invalids the commands of their doctors, to drudge through the wet for four hours in honor of Terence M’Manus. Some 10,000 or 12,000 people walked eight deep, some actually finding their own crape and gloves, and all being ready with an overflow of sympathy. There were a funeral car which was magnificent, and a coffin which “was not shaped the usual way, but like a box,” perhaps with some mystical meaning with which we are unacquainted. There was an Irish harper in full “bardic costume” – namely, wearing a white robe, which may possibly have been a familiar nocturnal garment. Finally, there was immense excitement and enthusiasm in Dublin, for, “so far as the people were concerned,” the funeral surpassed the funeral of O’Connell….

… a couple of brass bands, and one of drums and fife, played “The Dead March in Saul.” Towards the tail end of the procession was a stout individual, in a very uncomfortable seat, and holding in front of him a very large Irish harp. This feature provoked some laughter from those external to the processionists; the faces of the latter being very grave, and their personal demeanor certainly unexceptional. The procession moved at a slow pace through Great Britain Street, Capel Street, along the quays, over the King’s Bridge, and back through James’s Street, Thomas Street, into Dame Street, Westmoreland Street, and over Carlisle Bridge into Sackville Street. This occupied a couple of hours. Groups of people lined the streets, and occupied hall doors in all places where the advent of the funeral was expected…

Belfast Weekly News, Sat 16 Nov 1861 p2

I think one reason the funeral procession got a lot of attention was because it was quite hotly political. This last clipping is in the middle of a complicated criticism and counter-criticism of the coverage:

…There are fifteen thousand Dublin citizens, according to our contemporary, who by walking at the back of the Irish harper from an Abbey Street tavern on Sunday last, declared their unchanging fidelity to the old cause…

Dublin Weekly Nation, Sat 23 Nov 1861, p14

Ship Tavern

The obituary states that Joseph Craven

…has for the last twenty years been performing in the Ship Hotel

Irish Times, Wed 8 Sep 1869 p2

The Ship Hotel and Tavern at 5, Lower Abbey Street, Dublin, was established in the early 19th century. As usual for hotels and pubs at that time, it employed musicians to play background music every evening. In the early days these were classical performers on violin and piano, but in 1829 the Ship was taken over by a new proprietor, Bernard Mulvaney, who hired “The celebrated Irish harper from Belfast” to play every evening (The Pilot, Fri 20 Nov 1829 p2); I think this first harper was John McLaughlin, but I haven’t yet researched him properly. Anyway, from then on, the musicians at the Ship were almost exclusively harpers or harpists.

The Ship advertised regularly in the Dublin newspapers. The adverts are a fascinating series. An advert is drafted, and then re-used for a few weeks or months, and then a new one is written. Each re-writing gives different information. Often the music is not mentioned, and when it is we only get a snippet of information, often not even the performer’s name.

Over the years the proprietors of the Ship Tavern hired a number of different harp players to provide music every evening. Some of them were our traditional harpers; others were classical pedal harpists, including “The celebrated harper, Mr. Quinn” (Dublin Weekly Register, 2 Jun 1838) who was “a pupil of Bochsa” (Freemans Journal, 8 Jan 1842). There were also Welsh harpers, including “Mr Edward Jones, the inimitable Welch harper”, who performed at the Ship on his prize harp which he had won at the Abergavenny Eisteddford in 1848 (Advocate, 11 Apr 1849); you can hear a recording of this harp played by its current owner Huw Roberts

Adverts for the Summer and Autumn of 1852, through to the end of September, give the full bill of fare, and state “Quinn, the celebrated harper, performs every Evening” But from the beginning of October 1852 (the earliest I have seen so far is 2nd Oct) the same advert is printed with Craven named as the harper instead:

SHIP,

HOTEL, TAVERN, AND DINING ROOMS

5, LOWER ABBEY-STREET,

SACKVILLE-STREET,

(Rere Entrance, 14, Sackville Place.)

______

A Table d’Hote daily, from 5 to 7 o’clock [ s. d.

Dinner, Fish, Soup, Joints, &c., &c., .. .. 1 0

Ditto, Steaks, Chops, or Cutlets, .. .. .. 1 0

Lunch, ditto., ditto., .. .. .. .. 0 8

Ditto, off the Joints, hot or cold, .. .. .. 0 6

Breakfast, Tea or Coffee, with Eggs, .. .. 1 0

Ditto, Steak, Chops, or Cold Meat, .. .. 1 3

Oysters, Fresh from the Beds every Morning, per

Dozen, .. .. .. .. .. .. 0 6

Bread and Butter .. .. .. .. .. 0 2

Kidney, Bread and Butter .. … .. .. 0 5

Glass of Ale and Sandwich, .. .. .. 0 4

Fine Old Sherry, per Bottle, .. .. .. 4 0

Ditto, Pint .. .. .. . .. .. 2 0

Old Crusted Port, per Bottle .. .. .. 4 0

Ditto, Pint .. .. .. .. .. … 2 0

Jameson’s Prime Old Whiskey, per Tumbler, .. 0 4Jamaica Rum, Cognac Brandy, Liqueurs, Lemonade, Soda Water, Ginger Beer, &c., &c., charges equally moderate

Dublin Weekly Nation, Saturday 9 October 1852 p2

BEDS, per night, 1s.

______

Craven, the Celebrated Irish Harper, plays his popular and much admired Airs every Evening.

The London Times, Bell’s Life, Illustrated News, Punch, Liverpool Journal, Saunders, Freeman and NATION Newspapers, taken in, and may be had for half-price the day after publication.

So “twenty years” seems a slight exaggeration; but it implies Craven was working there for almost 17 years from October 1852 through to his death in September 1869.

In 1853 an new shorter advert appears:

SHIP HOTEL AND TAVERN,

Freeman’s Journal, Monday 22 August 1853

LOWER ABBEY-STREET,

Five Doors from Sackville-street.

Tourists and Excursionists visiting Dublin will find at the above house the most ample accomodation at very moderate charges.

A Table d’Hote every day from Five to Seven o’Clock.

Dinner (Soup, Joints, &c.) … … 1s 3d

Beds per night … … … 1s 0d

An excellent Billiard Table on the premises.

“The Harp that once.”

Mr. CRAVEN performs on the Irish Harp in the Coffee-room every evening from Seven o’Clock.

I don’t really understand the whole story yet; I am missing a lot of pieces of information about the Ship, and really I am only interested in the harpers. There is a huge research project here to piece together all the information about the Ship Tavern, its proprietors and customers, to tell its story from its beginning in the early 1800s, through to its mention in James Joyce’s Ulysses, to its final destruction by British artillery in 1916. Somewhere out there, there must be a photo or drawing of the Ship before it was destroyed.

Anyway there was a new proprietor on 17th October 1853, John Cunningham, who announced that he was to run the Ship “in an entirely different style from that in which it had hitherto been carried on”, and that “the service of a celebrated Irish Harper have been secured, who will perform every Evening, commencing at 7 o’Clock” (Saunders’s News Letter, Mon 7 Nov 1853 p3). The harper is not named, but I think it was still Craven, just carrying on as before. He was certainly working there a few months later: “…the services of Mr. Craven, the celebrated Irish harper have been secured, who will perform every Evening from Seven o’Clock” (Dublin Weekly Nation, Sat 4 Feb 1854 p16)

Similar adverts appear throughout 1854, until the last I have seen naming Craven on 14 Apr 1855 (Freemans Journal p1). From 1855 through to 1868, the proprietor John Cunningham regularly placed adverts for the Ship in the papers, but none of the ones I have seen name the harper, instead saying things like “a celebrated Irish harper in attendance every evening” (Catholic Telegraph Sat 1 Sep 1855 p1); “a celebrated Irish harper performs every evening from 7 o’clock, it being the only house in Dublin where a Harper performs” (Dublin Weekly Nation, Sat 29 Dec 1855 p16); “one of the best of the genuine Irish bards nightly discourses…” (Dublin Evening Post, Thur 16 Apr 1868 p2)

In April 1868, The Prince and Princess of Wales (Albert and Alexandra) made a Royal visit to Dublin, and many streets were decorated, with businesses competing to put loyalist mottoes and emblems outside their buildings. A review of the decorations on different Dublin shop-fronts, street by street, describes the Ship. I think this is a bit of paid product placement in this article:

… LOWER ABBEY-STREET

The Evening Freeman, Thursday 16 April 1868 p4

Messrs. Smith and Co. Balbriggan Hosiery Warehouse – A large star between the initials A. A.

The Northumberland Hotel – The Prince’s plume and the initial letters of Albert and Alexandra.

One of the handsomest displays during both day and night was that made by Mr. Cunningham at his celebrated hotel, “The Ship,” Lower Abbey-street. Projecting from the upper story was a green standard, bearing the Irish harp &c., and pendant from it, in a beautiful festoon, were the flags of all nations in all their bravery. The effect was very pleasing, and here, en parenthesis, we may say that English visitors, of whom there will be many during the coming period of national festivity, should be reminded that “The Harp that Once” – the Irish harp is not yet wholly silenced; it is to be heard still resonant and full of melody as when it sounded in Tara’s Hall to “Chiefs and Ladies Bright,” in the Ship Tavern, where one of the best of the genuine Irish bards nightly discourses the sweet strains of Irish melody on the national instrument.

From the establishment of Mr. M’Comas, tailor, there was a nice display of flags.

I don’t know if this was still Craven or if he had already been replaced. I suspect he continued to play every evening in the Ship Tavern until shortly before he died. But I don’t have any proof for this, only the line from the obituary that he had been there “for the last twenty years”.

Death and legacy

…died yesterday afternoon in St Vincent’s Hospital…

Irish Times, Wed 8 Sep 1869 p2

…He leaves a wife and family…

His death record does not add very much information; it records that he died on 7th September 1869, in St Vincent’s Hospital, that he was male, married, aged 53, and his occupation is given as “Harper”.

St Vincent’s hospital was at 56 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin. The hospital still runs from a new site out away from the city centre.

I found a death record for Anne Craven, “widow of a musician”, who died age 53 on 13th February 1878. I wonder if this was Joseph Craven’s wife? She would have been about 9 years younger than him. She died at 13 Marlborough Street, which is about where the Marlborough luas stop is now; the entire block has been redeveloped. Her death was reported by John Craven, of the same address. This may be their son.

Joseph Craven was not forgotten. A couple of months later, a poem was written as a tribute to him:

THE DEAD HARPER

“F.F.” sends some verses inscribed to the memory of Joseph Craven the celebrated “Irish harper,” from from which we select the following stanzas: –

The harp’s wild note is heard no more,

Death stilled the minstrel’s hand.

And who will now those sweet strains pour

Which breathe of our dear land?

He touched the soul as by a spell,

Our thoughts from earth were led –

The harp lies mute enough to tell

The bard of Erin’s deadHe’s dead! and yet it seems a dream:

His wild harp still I hear;

Again each well-remembered strain

Is ringing in mine ear.

But I awake to find the truth –

The dear delusion fled:

My old and trusted friend of youth,

The Bard of Erin’s dead.Farewell, dear friend, since I am left

Dublin Weekly News, Saturday 27th November 1869

This last sad lay to sing –

How soon are mortals here bereft

Of all to which they cling!

But thou shalt wake the harp of gold,

Where angel’s wings doth spread,

And dwell in light and bliss untold –

The Bard of Erin’s dead.

Perhaps we shouldn’t wonder what the other verses were, that the editors selected these three from.

Slightly more prosaically, Craven’s name was later used in advertisements for the Ship. Five months after Craven had died, John Cunningham announced that he had engaged the traditional Irish harper Hugh O’Hagan to play every evening at the Ship. But these adverts naming O’Hagan only seem to run from February to April 1870 (I am probably missing some at each end).

It is from March 1872 that a new and gushing advert appears, which mentions how Craven used to play at the Ship. This is a whole series of adverts from 1872 through to 1874, all using the same text, under the title “The National Music of Ireland”. Most do not name the “young but brilliant performer on the harp” who has been engaged, but this one adds a paragraph at the end:

THE

Irish Times, Sat 16 Mar 1872 p1

NATIONAL MUSIC OF IRELAND

___

THE SHIP HOTEL AND TAVERN

LOWER ABBEY-STREET

(ESTABLISHED 1810)

Became, many years ago, one of the most favourite resorts in Dublin, the Proprietor having engaged a celebrated Irish Harper, who delighted his hearers with the splendid Music of our Native Land – introducing several remarkably fine airs and spirit-stirring marches of the bards, then not generally known in the city. For over a quarter of a century poor Craven, who was deprived of vision, played the melodies of Erin there, and the accuracy and pathos of his execution were fully acknowledged. Since Craven’s death Mr. Cunningham has been fortunate enough to secure the services of another young but brilliant Performer on the Harp, being determined, notwithstanding the great expense, to maintain the name his Establishment has but justly made through this agreeable and rare attraction. Visitors to the Metropolis may not be aware that the Ship Hotel is the only house in Dublin that thus encourages the popularity of the Symbolic Emblem of our Native Land, and in his efforts to preserve that love of Irish Music and attachment for the instrument

“whose sounds were made for the pure and free,”

[the] proprietor should be sustained by public appreciation.

Owen Lloyd the excellent musician who at present plays in this Establishment is an admirable executant, and gives not only all the favourite airs of Ireland with beautiful effect, but also the most popular and newest quadrilles, galops, &c., so that everyone who hears him feels genuine pleasure in listening to the pretty music emitted from the

“Dear Harp of our Country”

So much for Craven’s legacy; while Craven’s name and the idea of the old inherited harp tradition was being marketed, that was no longer the reality on the ground. Owen Lloyd was not a traditional Irish harper; he was a classically-trained pedal harpist, a student of the Welsh pedal harpist Aptommas and later of the Scandinavian pedal harp virtuoso Adolf Sjöden; he played a double-action “Gothic” style pedal harp. Owen Lloyd was later to become an Irish language activist, and was an important figure in the Gaelic revivals of the 1890s and early 1900s, developing and teaching classical-style harp technique on gut-string lever harps to start a new lineage of modern Irish harp playing which is mainstream today. And so the old tradition was sidelined and brought to an end.

We have one final memory of Joseph Craven, I think. He isn’t named, but the description best matches him. The article is a discussion of the older tradition of commercial premises displaying a pictorial sign-board instead of having the name of the business written above the shop front. The article was prompted by the sale of the Ship Tavern in 1898:

“The Ship”, one of the last of the picturesque landmarks in Dublin, was once the resort of many convivial spirits. For many of its frequenters the blind harper who performed there was one of its chief attractions. This old bard drew forth exquisite strains of music from his instrument, and many were the regrets when he passed over to the great majority.

Irish Independent, Monday 14 November 1898 p4

After that I don’t think Craven was ever mentioned. I never knew about him until I started this project to investigate the 19th century traditional Irish harpers, and I started seeing his name in the old newspapers.

These just get better and better. I am seized with envy that Craven got to share the stage with a ventriloquist, a personal ambition of my own that went, sadly, unfulfilled.

And what a blessing to have such a long run at ‘The Ship”. Think of it, at least seventeen years without him having to hear the words: “Here. Put this on.”

This research is priceless.

Seán Donnelly pointed out to me that the chariot is now owned by the National Museum of Ireland, and has been restored and is on display in Derrynane House. You can see a photo of the chariot at the Derrynane House website, and there are a couple of closeups at The Irish Aesthete.

Brilliant, really enjoying these biographies, thanks for making this research available. I fully agree with the comment above – “This research is priceless”.

I found both a plan, and a drawing of the front of the Ship Tavern.

The plan was drawn in 1893 as part of Goad’s insurance maps of the city of Dublin. I have highlighted the Ship Tavern. This plan gives a lot of technical details about the structure of the buildings; you can look at this useful key to Goad’s plans online at the National Library of Scotland. The Ship is shown with four storeys to the front on Lower Abbey Street, and two storeys to its long rear which has an entrance on Sackville Place. The two sections are joined by a square single-storey atrium with a large glass skylight.

The drawing shows the North side of Lower Abbey Street, from Shaw’s Dublin Pictorial Guide and Directory, 1850. I have highlighted the Ship Tavern at no.5. You can see what looks like three tall ground-floor windows and the entrance door on the right. You can also see the signboard hanging between the first floor windows.

The 1850 directory index says

The only building on this drawing that is still standing is the house on the very right hand end corner, no.9, which is now the Flowing Tide pub.