John MacLoughlin was a traditional Irish harper in the first half of the 19th century. He had an interesting working life in Dublin, playing before the King, working in taverns and ending up in poverty. This post is to gather together the different scattered references to him, to build a picture of his life and work.

Birth and education

At the moment I don’t have any information about when John MacLoughlin was born or where he went to learn to play the harp. He was later described as “one of the young harpers of the Belfast School” (O’Curry’s lectures vol 3 p298) and other sources also say he was from the Belfast Harp Society, and so I think it is likely that he learned to play the traditional wire-strung Irish harp at the Irish Harp Society school in Belfast under Arthur O’Neil. His name does not appear in the list of students on 2nd Jan 1810; he may have been admitted to the school after the expulsion of James O’Neill in June 1810. If so, we might imagine that John MacLoughlin may have been born around the late 1790s, perhaps between 1795 and 1800.

Playing for the King

We first meet John MacLoughlin in 1821, when he was one of the traditional Irish harpers who played for King George IV in Dublin in August of that year.

There were two events on two subsequent days. On Thursday the 23rd August the the Corporation of Dublin gave a banquet to the king in the round room at the mayoralty house, and four harpers played as part of the music at this banquet. The next day, Friday 24th August, the King visited the Royal Dublin Society at Leinster House. Three harpers played in the gardens where a tent city had been erected for the King.

We know John MacLoughlin played on the Thursday evening in the banquet, because we have his name listed for the programme. But we don’t know who the three harpers who played on the Friday in the tent were. I discuss on my post about James McMonagal how John MacLoughlin was not named in Patrick Byrne’s later anecdote about the events, though McBride, Rennie and McMonagle were named by Byrne. Perhaps MacLoughlin was not able to play on the Friday. Or perhaps Byrne never knew MacLoughlin, or held a grudge against him. I don’t know.

VALENTINE REANNEY, JAMES MAC MONAGAL,

EDWD MAC BRIDE AND JOHN MAC LOGHLIN,

Irish Harpers.

This tune list is very interesting and I have discussed some of the tunes on my tune list post. It shows us the kind of repertory that these four traditional lads were playing. I think all four of them had learned the harp at Belfast from the harper and tradition-bearer Arthur O’Neil, and so presumably these tunes were all taught to them in the Belfast school by Arthur O’Neil.

I also find it interesting that all of the tunes are given with bilingual titles, in Irish and in English. I don’t know who was responsible for drafting this programme, who would have provided the Irish language titles. We have very little information about the Irish language abilities of the traditional harpers in the 19th century. We know their teacher Arthur O’Neil was an Irish speaker, but the Irish language was in very rapid decline in the beginning of the 19th century, especially in the north-east where most of the 19th century harpers came from. We know that James McMonagle did not speak Irish, but I don’t have any information about John MacLoughlin.

Other descriptions of the royal banquet talk about who was there, how the room was decorated, how the harpers were dressed in costume, who the other musicians were, and other interesting background detail. You can read about these on my posts about Edward McBride and James McMonagle. I think the handwritten annotations on the programme are the names of some of the aristocrats who were at the banquet.

One snippet of information might be relevant to John MacLoughlin. Hubert Burke describes the event in his book Ireland Sixty Years Ago, (London, 1885 p20) and he mentions the “Irish harpers, two of whom were sent by the Lord of Shane’s Castle, dressed in the ancient costume of the O’Neills”. I have wondered on my other posts which two these were. I have already pointed out how Edward McBride and Valentine Rennie had been working together as a kind of double-act even before they had finished studying in Belfast; by 1821 McBride was teacher in Belfast and Rennie was working in Dublin. I have wondered if McMongal and MacLoughlin were the two who had been working for Viscount O’Neil at Shane’s Castle. But at the moment we don’t have enough information about either of them to know.

The Bank Tavern

Six years later, in 1827, we find John MacLoughlin working in a tavern. I think this was a common way for the traditional harpers to make a living. I think they would aspire to get work playing for the aristocracy in the big houses, but there were not enough patrons like that and too many young professional harpers, and so playing in hotels in the towns and cities was often where they ended up.

I think that some people with power and influence in the musical world disapproved of this, and thought it was morally dangerous for the harpers to be working in taverns, and this is one reason why the Harp Society school was defunded and shut down in 1839-40, which led to the end of the inherited tradition. See my post on “two letters to Edward Bunting” for more about these attitudes.

I am sure that most of the time the harpers like John MacLoughlin played every evening in the hotels and taverns and that there is no record of where they were and what they were doing. But sometimes the proprietor would place an advert in the newspapers, and sometimes the advert names the musicians he has hired to provide background music for the customers.

MAC LOUGHLIN,

Saunders’s News Letter, Wed 21 and Fri 23 March 1827 p3

THE celebrated HARPER, from the Belfast Harp Society, and whose exquisite performance was so much admired by the Officers of the Third regiment, that they presented him with a Splendid Harp, performs every evening, (Sundays excepted,) at THE BANK TAVERN,

TRINITY STREET.

The Bank Tavern was at 13 Trinity Street, which I think was on the corner of St Andrews Lane where the Pichet French restaurant is now. The buildings have changed a lot and the 1830 valuation lists three premises between St Andrews Lane and Dame Lane, nos. 13, 14 and 15. I don’t think this was The Bankers Bar which is at no. 16, a couple of doors further along from where The Bank Tavern was. The proprietor of the Bank Tavern in 1826 was William Sharpe, though his adverts don’t mention music (Saunders’s News Letter Sat 11 March 1826 p2, Dublin Evening Post, Sat 3 June 1826 p2).

We will deal with the “splendid harp” later on.

Anyway, one week after the first advert mentioning MacLoughlin playing there, The Bank Tavern was offered for sale, with MacLoughlin featured as part of the deal:

HOUSES & LANDS

Saunders’s News Letter, Wed 28 March 1827 p4

BANK TAVERN,

TRINITY STREET.

TO BE DISPOSED OF,

THE Interest in the above well established House, being decidedly one of the best situations in Dublin, with fittings-up, and fixtures complete. There is also a Retail Spirit Shop attached, license paid.

If not shortly disposed of, it would be let to a respectable Tenant weekly.

☞ Mac Loughlin, the celebrated Harper, from the Belfast Harp Society, performs every evening.

The business was finally sold on 9th May 1827 (Saunders’s News Letter, Wed 9 May 1827 p4). By October, the new proprietor is advertising singing with piano accompaniment as the musical attraction every evening (Saunders’s News Letter, Thur 18 Oct 1827 p3), so MacLoughlin had obviously moved on somewhere else.

The Ship Tavern

I think John Mac Loughlin may have been performing regularly at the Ship Tavern in Dublin for four years, from November 1829 until January 1834.

Starting in 1829, we have intermittent advertisements for the Ship Tavern which mention a harper performing every evening, but they don’t tell us the harper’s name.

SHIP TAVERN AND COFFEE-HOUSE

The Pilot, Fri 20 Nov 1829 p2

No. 5, LOWER ABBEY-STREET

(OPPOSITE THE ROYAL HIBERNIAN ACADEMY)

BERNARD MULVANY

RETURNS his sincere thanks to his numerous Friends and the Public, for the kind support he has received since he commenced business, and to assure them that every article in the above line shall be of the best kind, and every delicacy of the season shall be provided. In consequence of the

FALL OF THE MARKETS

He submits the following rates: –

Breakfast (Tea or Coffee) ___________ 10d.

Ditto, with Eggs or Meat, (hot) &c. _ 1s. 0d.

Dinner (roast beef) _________________ 1s. 3d.

Ditto (beef steak) ___________________ do.

Ditto (mutton-chops) _______________ do.

Ditto (veal cutlets) _________________ do.

Ditto (boiled mutton) ______________ do.

Ditto (corned beef) _________________ do.

Mutton chops or cold meat Snack, 5d.

B. M. has engaged the celebrated

IRISH HARPER,

FROM BELFAST.

He will commence this evening at seven o’clock, and continue during the winter sea[s]on.

Billiard-rooms and Cigar-rooms attached to the Establishment.

Red Bank, Burren, Carlingford, and Malahide Oysters fresh every day.

The adverts refer to “The Celebrated Irish harper from Belfast” (Freemans Journal 6 Aug 1830, 3 Nov 1830). The next year, the description changes, and he is “The celebrated Irish Harper from Belfast, who won the two gold medals from the Belfast Club” (FJ 14 Feb 31, 21 Apr 31). We are told that the harper plays “every Evening from Seven till Twelve o’Clock” (FJ 9 Nov 30, 21 Nov 31, 1 Jan 32, 24 Jan 32). By November 1833, Bernard Mulvaney was dead and his widow was running the Ship; her advertisements say “A Harper plays every night, from Seven until Twelve o’Clock, except on Sundays” (Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent, 2 Nov 1833, FJ 9 Nov 33).

I am not sure what the “Belfast Club” refers to.

A couple of references in January 1833 and January 1834 say that John MacLoughlin played the harp at the Ship Tavern. So, while it is possible that it was one of MacLoughlin’s classmates who was playing there during 1829-32, I think it is fairly likely that it was MacLoughlin all the way through.

The Ship Tavern was at 5, Lower Abbey Street, Dublin. It became known as a place where there was a harper playing every evening. From 1834 through to 1852 the Ship hired a classical pedal harpist, and two Welsh triple harpists (apart from 1847 when an Irish harper, Fitzpatrick, briefly worked there). From 1852 until 1869 the Irish harper Joseph Craven was in residence, and in 1870 the traditional Irish harper Hugh O’Hagan worked there. After O’Hagan, the classical pedal harpist Owen Lloyd worked there. The Ship Tavern is mentioned in James Joyce’s Ulysses, but the building was destroyed by British artillery fire in 1916, and though the site was redeveloped, the Ship never re-opened.

O’Connell procession

We have accounts of John Mac Loughlin performing in processions through Dublin for Daniel O’Connell, “the Liberator”.

In a reminiscence 30 years later, George Petrie describes MacLoughlin playing the harp in a procession in 1829, though I think there are problems with this account:

… Many of us must, like myself, remember the triumphal procession of O’Connell through the leading streets of our city in 1829, after the passing of the Emancipation Act. The hero of the day was seated in a triumphal car, richly decorated with laurels; standing on his left hand, his henchman – one of my boy friends – the noble and lionhearted, and yet gentle, but not overwise Tom Steele ; and seated before, but below them, a venerable minstrel, with abundant silvery locks and beard, arrayed in the supposed costume of the bardic race, and apparently drawing from his harp the joyous melodies of his country fitting for the occasion. It is true that he might as well have been a ‘man who had no music in his soul’, striking an instrument which could give forth no sound: for the never-ceasing Irish shout, which I believe is allowed to be far superior to all other shouts, of the assembled thousands who preceded, and surrounded, and followed the car, was a jealous shout, and would allow no other sound to be heard. The harp of that day was the one which is now mine; and the harper, whose appearance indicated a centogenarian age, and from whom, in a subsequent year, I bought it, was M’Loughlin, one of the young harpers of the Belfast school.

Eugene O’Curry, On the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish (1873) vol 3 p297-8

I checked the newspapers for O’Connell’s procession on I think Tuesday 2nd June 1829. The procession happened when he returned from London after the passing of the Catholic Emancipation Act. He was met at the harbour in Kingstown (now Dún Laoghaire) and his carriage processed back through the city centre to his house on Merrion Square; there were thousands of people crowding the streets to cheer for him but there is no mention of a harper, or of Tom Steele, and his vehicle is described as a “carriage drawn by six grey horses” (The Pilot, Wed 3 June 1829 p1), as if it were just an ordinary vehicle. There is no mention of the spectacular triumphal car which was used on later processions, which had tiered steps for O’Connell, his henchmen and the harper as described by Petrie.

I wonder if Petrie may have got the year and the occasion wrong, or if the 1829 accounts just don’t bother mentioning the bizarre vehicle. You can see the car preserved at Derrynane House, and you can see pictures of it in action on my write-up of Joseph Craven. The Derrynane website says the vehicle was presented to O’Connell in 1844, but the 1844 newspaper report (Illustrated London News Saturday 14 Sept 1844 p165) says the car was used as early as the procession in 1832 (presumably an error for January 1833).

We have contemporary descriptions of John MacLoughlin playing the harp on the triumphal car in a procession on Monday 7th Jan 1833. This was to celebrate that O’Connell and Ruthven had been elected MPs for the Irish Repeal party, in the UK General Election of 1832.

…The carriages formed up Abbey-street and Sackville-street, from the door of the Arena. At this point the triumphal car, drawn by six greys, arrived at half-past nine, and shortly after Messrs. O’Connell & Ruthven took their seats on gilded chairs, placed side by side, on its summit, which was elevated three steps above the door, whereon stood Mr. Thomas Steele. The morning was foggy and chilly, and Mr. O’Connell sat muffled closely in his cloak, thick neck-cloth, and travelling cap, decorated with lilies and shamrocks. During the procession he seldom uncovered his head, and then only for a short time. –

Belfast News Letter, Fri 11 Jan 1833 p4

Mr. Ruthven wore neither cloak nor surtout, and stood with his hat off, and silver hairs uncovered, during the greater part of the day. At the feet of the members, on the upper step, stood two pages, about eight or nine years of age, in blue frocks, yellow breeches, white stockings, with rosettes in their shoes and at their knees, Spanish hats and white feathers; each bore a white banner with the harp of Ireland imprinted thereon, and the inscription “Erin go bragh,” &c. &c. On the lower step sat M’Laughlin, the Irish harper, of the Ship Tavern, clad in the regal mantle, assumed by the ancient bards of Tara, a high conical cap, and a comely flowing wig, and beard of white horse hair, playing “Garryowen” and “Patrick’s Day,” neither of which, however, could be heard a few yards beyond the wheels of the car. We understand that he, the pages, two kettle drummers, and a trumpeter in the pageant, were indebted to the wardrobe of the Theatre Royal for their “dresses and decorations.”…

The article continues with a description of the car, and of the rest of the parade.

Both Garryowen and Patrick’s Day are listed on the 1821 programme for the Royal banquet.

His harp

We have a reference to John MacLoughlin being presented with a harp, and we have a reference to a collector buying a harp from him, but it is hard to collate this against the rest of his life story.

The original idea of the Irish Harp Society in Belfast was that once a pupil had finished their studies, they would be examined by the Gentlemen, and then if they were up to standard they would be presented with a certificate stating their musical ability and general personal good conduct, and they would also be presented with a harp, so that they could go out and make their living as a professional or “artisan” harper. However, there seems to have been a great shortage of harps during the time of the first Belfast Irish harp Society from 1808 through to when it came to an end in about 1812; an eyewitness says that they met “five or six Belfast harpers” in county Sligo some time before 1817, and continues, “they were in general excellent performers, and enthusiasts in regard to their national airs; but they were very indifferently furnished with harps” (Irish Harp Society pamphlet, Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections MS4.37.10). I think that the Harp Society had run out of money and so was not able to buy enough harps for everyone. So it is not clear to me what happened; whether the boys toured in groups so they could share one harp between two or three of them.

The situation changed from about 1820 when the newly reconstituted Irish Harp Society, flush with money from the gentlemen subscribers in India, commissioned new, floor-standing wire-strung Irish harps from the Dublin harpmaker John Egan.

George Petrie discusses the Egan wire-strung Irish harps of the 1820s, and says he owned one which belonged to MacLoughlin:

I have now, therefore, only to say a few words in reference to the harps manufactured in our own time.

Eugene O’Curry, On the Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish (1873) vol 3 p297-8

As far as I know, these harps are all the manufacture of Egan, the eminent Dublin harp-maker, and owe their origin to the necessity of providing instruments for a new race of harpers, the pupils of the school of the Belfast Harp Society. These harps were of good form and size, about the height of pedal harps, rich in tone, and of excellent workmanship. But they were wholly without ornament, and had nothing about them to remind us of ‘the loved harp of other days’. Where are these harps now ? To what purpose have they been applied, now that their players have disappeared from amongst us ? I cannot say. One, indeed, is in my own possession, and is an existing memorial of a great triumph of religious liberty…

[description of O’Connell’s procession, transcribed above]

…The harp of that day was the one which is now mine; and the harper, whose appearance indicated a centogenarian age, and from whom, in a subsequent year, I bought it, was M’Loughlin, one of the young harpers of the Belfast school.

If we strip away Petrie’s florid language and opinionated comments, I think this is very clear; John MacLoughlin owned and played an Egan wire-strung Irish harp, which he played in an O’Connell procession, and which George Petrie afterwards purchased from MacLoughlin.

Note that Petrie says the harpers have “disappeared”. The lecture where Petrie’s letter was read out was delivered on 26th June 1862, and published in 1873. If we check my timeline of old harpers we can count at least 12 traditional harpers still working professionally in Ireland in 1862: Byrne, Hanna, Fraser, Craven, FitzPatrick, Murney, Patrick, O’Hagan, Smith, Griffin, Moore, and Hardy, as well as Begley in England and Wall in America, and also a few amateurs. I think that Petrie bears a lot of responsibility for the marginalisation of the harpers and the end of the inherited tradition.

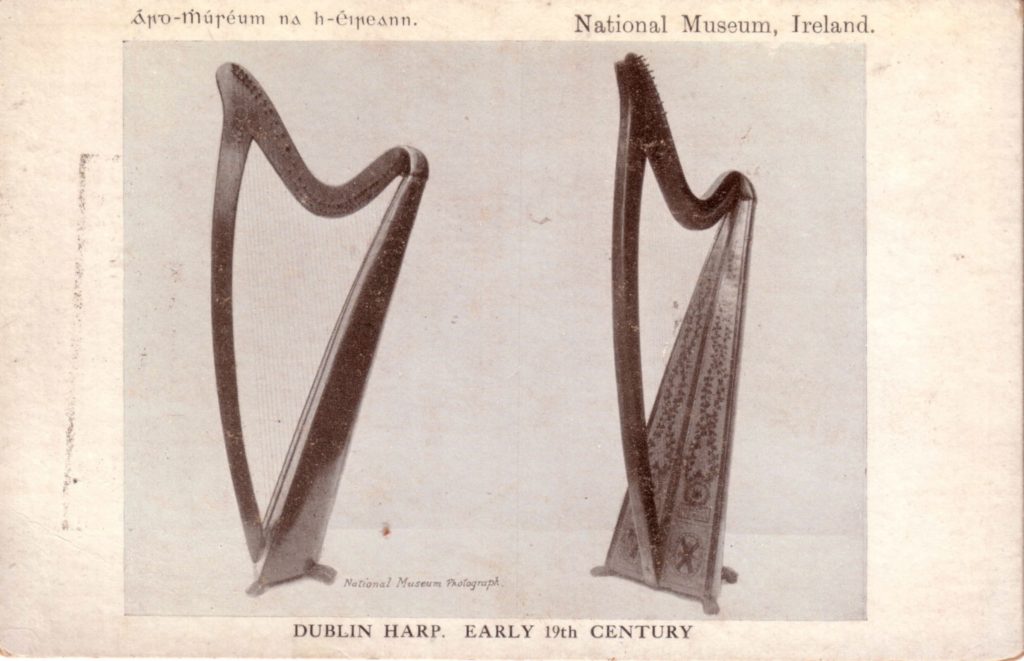

John MacLoughlin played for the King in August 1821, and so he must have had a harp to play on then. We don’t know what his harp was like or where he had got it from. I already suggested above that perhaps McMonagal and MacLoughlin might have been the two harpers provided for the Royal occasion by Viscount O’Neil of Shane’s Castle. And if so, it is possible that one of the harps that O’Neil had made for the occasion might possibly have been NMI DF:1905.24, which is attributed to John Egan.

The National Museum of Ireland purchased this harp in 1905, at the estate sale of Margaret Adeline McDowell, of the famous McDowell jewelers family in Dublin. But I don’t know where they got it from.

We also have the reference to the “officers of the Third Regiment” presenting MacLoughlin with “a splendid harp”. We don’t know when this splendid harp was presented to MacLoughlin, only that it must have been before March 1827.

The 3rd Regiment is what the Scots Guards were called at that time. I checked Frederick Morris, The History of the Scots Guards (1934) volume 2, which covers the early 19th century. Obviously he does not mention MacLoughlin or the harp, but he does describe how “in 1821 the Guards were called upon to find a battalion for Dublin. The routine of stations became then: The Tower – Knightsbridge – King’s Mews Barracks… – Portman Street Barracks – Lower Westminster… – Windsor and Dublin. Changes of quarters between stations took place every six months, except in the case of Dublin, which was occupied for a year… In 1824 the 1st Battalion took its first tour of duty in Dublin. In 1826… the 1st Battalion was sent to Manchester…” and that is about all he has to say about this period. He does give an index of the officers of the Regiment with their dates of service, but the index is 100 pages with about 25 men on each page so I don’t think we can work out who our officers were from this. He also says that the regiment was on duty for the coronation of George IV in January 1820, a year and a half before the King visited Dublin.

I wonder if the Officers presented a harp to MacLoughlin for the Royal visit in August 1821? But I don’t know how plausible this is.

At the moment I can’t tell if John MacLoughlin had one harp, or two harps. He could have got a harp before 1821, which he played on before the King. Then perhaps after that the officers were so impressed that they presented him with a second harp. George Petrie saw him playing for O’Connell, and bought a harp from him, and (if he had two) he would have been able to continue working at the Ship playing on the other one until he died.

But perhaps he only had one harp, the one the officers presented to him. In which case was the presentation before August 1821? Did the officers present the harp which he played on before the King? And if he only had one harp, which he used for the O’Connell procession, and also for playing in the taverns, when did Petrie buy it from him? Petrie says the procession was in 1829, and the purchase was “in a subsequent year”. But I think Petrie may have been mis-remembering the year, and I think he may have been describing MacLoughlin’s performance in the Jan 1833 procession. But MacLoughlin died in January 1834, and kept working until two days before he died, so when did the purchase take place? Did Petrie go to MacLoughlin’s death bed to buy the harp? Or did he buy it from the family after John MacLoughlin had died?

Also I wonder what happened to the harp that Petrie bought?

Death

MR. LOUGHLEN THE IRISH HARPER. – This ardent lover of his country, and its minstrelsy, died at his lodgings, 33, Upper Liffey-street, on Friday the 10th inst. He performed at the ship tavern in lower Abbey-street as usual on Saturday, though his last illness had commenced; and so anxious was he to provide necessaries for his family, that he arose from his sick bed on Tuesday and Wednesday evening. He attempted to perform again on Thursday night, but his lamp was nearly out; he died upon the following day, and now rests in Glasnevin burial ground, unconscious of the wants a desolate family experience.

Dublin Observer, Sat 18 Jan 1834 p7

My map shows places associated with John MacLoughlin. You can touch a place to see what it is, or click it to read more. Or you can open the map full screen

Most interesting, thanks for this!

Fascinating as always Simon! Thank you!

in 1838, four years after McLoughlin stopped playing at the Ship Tavern, Mrs. Bridget Mulvaney was brought before the police court in Dublin by an over-enthusiastic Police Inspector Sergeant, who alleged she was open after-hours selling drink. The transcript of the case tells us a lot about how the Ship was run, and the context for McLoughlin’s harp playing every evening from seven pm until twelve midnight. Mr. Dark is the policemen, Mr. Walsh is the Ship’s lawyer, and I think Mr. Cole is the judge or whoever is presiding.

This case is simple on the surface. The way I understand this is that they start by trying to argue it was advertised as a Tavern not a Public House. Mr Cole was having none of this. He was also not impressed by the argument that it was a very respectable place. But then the waiter gave his testimony that the Gentlemen were all dining in, and at that point Mr Cole was satisfied there was no case to answer.

but for us it tells us a lot about how the Ship was run. I think a Tavern was more like a restaurant nowadays, you would drink with your meal but you would not be served just drinks at a bar. We see that the room was a “coffee-room” not a “tap room” (a tap room would be like a bar, where the beer was on tap). The testimony of the respectable people who went there is interesting; the Earl of Roscommon and the students at Maynooth.

Notice also how women and lower-class customers were not allowed in.

I think this would be typical of these taverns and hotels at that time.

Robert Bruce Armstrong, The Irish and Highland Harps (1904) p100-102 describes an Irish harp made by John Egan in 1809, and presented to the newly formed Dublin Irish Harp Society. This is the harp usually referred to as “the patriotic present”. It was vaguely in the form of an 18th century harp but built up using 19th century workshop practices. It had fancy tuning pins and cheek bands and no bridge pins. It may have had brass wire strings though this is not clear.

Armstrong says (p102) that the harp had a handwritten label on the back saying that the harp was played at the Liberator’s chairing as M.P. for Dublin in 1832.

And we know that McLoughlin played for the chairing of the Liberator, Daniel O’Donnell, on Monday 7th Jan 1833, after O’Donnell was elected MP for Dublin in the 1832 general election. So presumably McLoughlin played this harp then.

Is this the harp that Petrie purchased from McLoughlin? Did Petrie write the handwritten label?

Armstrong says in 1904 “This Harp is in the possession of E. W. Hennell, Esq.” How might Hennell have got it from Petrie? What happened to Hennell’s collection after his death? (Hennell was also the owner of the 1821 concert programme reproduced by Armstrong).

I got a copy of Hennell’s will from the English Probate service. Hennell died on 17th September 1918 and his will was proved on 11th October 1918.

In the will, he appointed his brother, Reginald, one of the executors. He divided his money between his sister, nieces and nephew, and manservant. Everything else went to his sister-in law, Mary Hennell, widow of his late brother Montague.

So it looks like Mary Hennell may have got the harp and the programme along with his other collections.

I found two other different accounts of the O’Connell parade on Monday 7th Jan 1833, in the English newspapers. One of these accounts names the harper as “Paddy Kelly”. I don’t know if this is just an error.

I do not know who Paddy Kelly was. These reports seem more jaundiced and less factual than the others, and so it is possible that this was a mistaken or political reference to John McLoughlin. But I don’t know.