When I was doing my newspaper research a month or two back, I found quite a lot of mentions of tunes played by individual named harpers. I realised that I could usefully try to collate all these different references, to get some kind of overview of what were the most commonly mentioned tunes in the inherited Irish harp tradition through the 19th century.

My criteria here are very simple: I am looking for tune titles, played by traditional Irish harpers in the inherited tradition, playing the big wire-strung Irish harps, who learned to play the harp after the 1790s. This means I am not including tunes played by Patrick Quin or Arthur O’Neill or any of the other harpers who were active in the 1790s; this project is to look at the next generation(s). I am also not including the revival harpists such as Lady Morgan, Owen Lloyd or Treasa Ní Chormaic, even though they were positiong themselves as playing Irish harp. They had not learned in the inherited tradition and had no connection to it, but were working in the classical tradition.

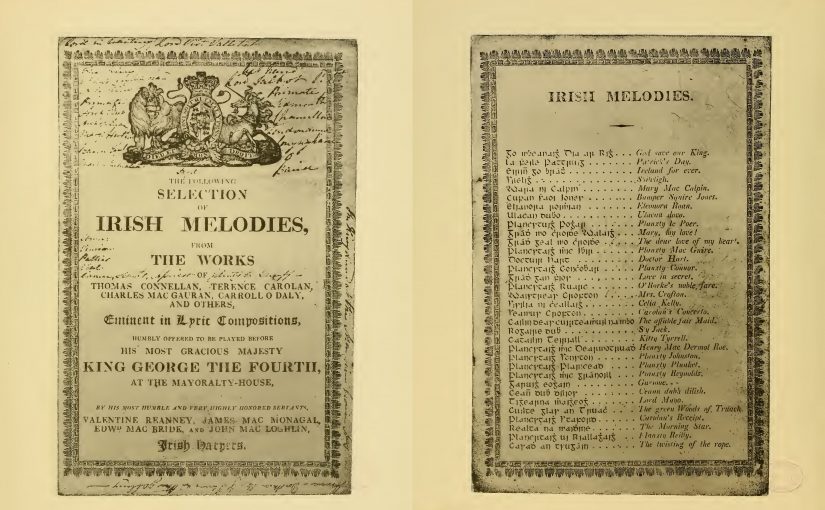

Of course a project like this is an interim work in progress, since I hope to find more tune lists in different places which might change the picture. But this post will summarise my initial findings. Most of this information is from newspapers, but there are a few extra lists, including Mat Wall’s tune list, and the programme for the performance for George IV in 1821 (shown in my header image, from Armstrong 1904, plate between p.52-3)

My spreadsheet combines the same tune listed for the same harper into a single entry. I have tried to work out what tune each title might refer to – during the 19th century, Tom Moore’s song titles become better known than the traditional title, especially in the kind of public forum that these tune lists come from. Its worth remembering the limits of this info; most of these titles come from public concert listings, and not from the teaching or the private tune lists of the harpers. We are told very little about their placing of themselves as traditional musicians; this is them out in the public entertainment world trying to make a living.

It’s worth pointing out that almost none of these titles have notations with them; the only notations I have found are two piano arrangements in Bunting’s manuscripts, which are tagged with Patrick Byrne’s name. All the others are just a title and a harper’s name; we have to look elsewhere to find out how the tune goes, and this can be very difficult because often two or more tunes might share the same title.

I have tried to identify each tune and group them under “normalised” Irish or English titles. After this process of grouping, I have got 153 different tunes in total. The biggest tune list is from Mat Wall in Philadelphia, and he is listing some very unusual American titles, so we could ignore these; there are 94 different tunes if we discount Wall’s eclectic mixture. We could also consider the tunes which are listed with more than one name beside them; there are 58 of these. This gets difficult because some of the listings give two, three or four names for the programme, and some programmes explicitly indicate “harp duet”. This means one performance in one programme gets an unusual tune into the “more than one harper” category. There are also some programmes that indicate certain items as being songs. These songs might or might not have had harp accompaniment. For the purposes of these lists, I am including them. But there is no right or wrong way to analyse this; it depends on the question being asked.

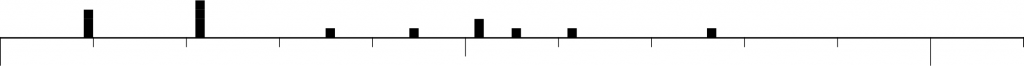

I have also made a little timeline for all appearances of each title in the context of the traditional harpers; the timelines all run from 1800 through to 1909.

Planxty Reilly (DOSC 140)

Planxty Reilly is joint top of our list, with 13 different names or harpers listed. Note we have three anonymous harpers; it is possible that these three are amongst the 10 named ones. But I am giving them the benefit of the doubt here.

1809 Miss O’Reilly and two other pupils at the Belfast Harp Society school, under the title Planxty Reilly.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, & McLoughlin, playing before George IV, under the title Plancstaigh Ui Riallaghaigh – Planxty Reilly

1835 Wall, under the title Planxty Reilly

1844 an anonymous harper, under the title Planxty O’Reily

1851 O Connor and Bell, a harp duet under the title Molly Carew (also Bell at a later concert under the usual title)

1861 Byrne, under the title Planxty Reilly

1876 Murney, under the title Planxty Reilly

Instantly we have a problem, in trying to work out what tune these harpers were playing. This shows us the limitations of working from tune lists! Donal O’Sullivan (Carolan 1958) lists four Reilly tunes that are sometimes attributed to Carolan. However as usual he has muddled up the titles and song lyrics between them. You can check my Carolan Tune Collation spreadsheet to see the DOSC numbers and the source references and titles.

DOSC 138 “O’Reilly of Athcarne” seems to me to be a bit less likely for our harpers, it is not usually attributed to Carolan and I haven’t ever seen it under the title “Planxty Reilly”. But it’s a nice traditional tune.

DOSC 139 is titled “Planxty Conor O’Reilly” in one 19th century source. You can see a published version in The Citizen, June 1841, no.21, and I suppose it has to be a contender for what some of the harpers were playing. I’m not finding a traditional recording of this tune.

DOSC 140 “Planxty Reilly” is perhaps the most likely contender for all of these harpers. It is certainly the tune for O’Connor and Bell in 1851, since Molly Carew is a song by Lover written to this tune. You can check my Old Irish Harp Transcriptions Project Tune List to see that DOSC 140 Planxty Reilly was published by Edward Bunting in both 1797 (no.46) and 1809 (p.19); he tells us that he got it from either Arthur O’Neill or Patrick Quin. I have not found a live transcription from a harper of this tune. It is possible that Bunting didn’t get it from a harper but lifted it from John Carolan’s harpsichord book of c.1747/8. I’m not finding a traditional performance of Planxty Reilly (DOSC 140). It looks to me like it may have been lost to the tradition, and re-introduced from the keyboard prints perhaps in the second half of the 20th century.

Seónin Ó Raghallaigh, fear gasda (DOSC 141) was transcribed live from a harper by Bunting in the 1790s, but is probably not by Carolan and would be less likely to be titled “Planxty Reilly”.

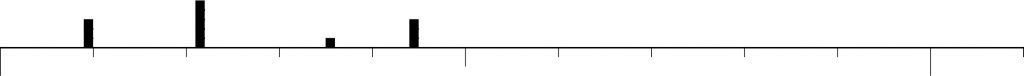

Patrick’s Day

Also sharing the No.1 slot in the top of the old Irish harper pops, is Patrick’s Day. No problems matching tune and title with this one! I have 13 names listed for this tune. Again, we have three anonymous harpers, who could be duplicates of the named ones.

1809 Miss O’Reilly and two other pupils at the Belfast Harp Society school, under the title Patrick’s Day.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, performing before George IV, under the title La fheile Padraig – Patrick’s Day.

1835 Wall, under the title Patrick’s Day

1846 Byrne, under the title St. Patrick’s Day

1851 O Connor and Bell under the title Patrick’s Day.

1863 anon under the title Patrick’s Day.

1876 Murney under the title Patrick’s Day.

Bunting tells us (1840 introduction page 82) that Patrick Quin had “fixed” this tune for the harp, and that he was very proud of this achievement. This is very interesting for me, as it gives us some contextual information as to how a tune can come into the harp tradition from the fiddle and dance traditions, in contrast to a tune like Planxty Reilly which was presumably composed for the harp and may have been transmitted within the harp tradition for over 100 years by the time of our tune lists.

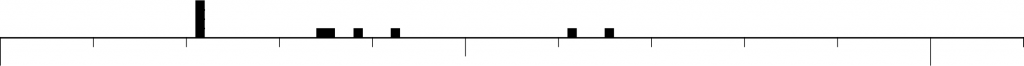

Uilleacán Dubh O

In at no.3 is the very solid and respectable traditional Irish harp tune Uilleacán Dubh O. I have 11 harpers listed for this tune. Two of these are anonymous, the classmates of Bridget O’Reilly at the Belfast school.

1809 Miss O’Reilly and two other pupils at the Belfast Harp Society school, under the title Ulligan Dulh O! Or the Song of Sorrow

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, performing for George IV, , under the title Ulacan dubho – Ulacan douo

1835 Wall, under the title The Song of Sorrow

1844 Frazer, under the title The Song of Sorrow

1844 O’Hagan and Branagan, under the title The Song of Sorrow

The Song of Sorrow is a song written by Thomas Moore, beginning “weep on, weep on”. Other songs have been composed to this tune.

This is a tune that probably was continually transmitted in the old Irish harp tradition from master to pupil right through the 18th and into the 19th century. Bunting made a live transcription notation of a version from the harper Denis O’Hampsey in the 1790s, which I wrote up recently.

The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls

We have five tunes which share joint 4th place, with nine different harpers listed. We could take them in any order but we’ll start with a piece of 19th century schlock.

1835 Wall, under the title The Harp that once

1842 McCurley, under the title Song – The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls

1843 anon, under the title The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls

1844 McEntegerth, under the title The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls

1854 O’Connor, under the title Song: The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls

1854 Byrne, under the title The Harp that Once in Tara’s Halls

1855 Bell, under the title The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls

1858 Begley, under the title The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls

1861 Hardy, under the title Song: The Harp that Once

Tom Moore’s famous song “The Harp that Once through Tara’s Halls” is said to have been composed to a traditional tune “Grádh mo chraoí” but I am not entirely sure about this. All of our harpers use Tom Moore’s title; even worse, three of our nine are singing it under that title, and so presumably singing Moore’s words in English to it. But I bet the audiences loved it. I also note that the dates for this one are rather later; it doesn’t appear in the lists before 1835.

Caitlín Triall

Also joint 4th place with 9 harpers listed is the traditional old Irish harp tune and sean-nós song, Caitlín Triall.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, performing for George IV, under the title Catailin Teiriall – Kitty Tyrrell

1835 Wall, under the title Blame not the Bard

1838 Byrne, under the title Kitty Tyrrell

1842 McCurley, under the title Blame not the Bard

1861 Hardy, under the title Blame not the Bard

1865 Begley, under the title Oh Blame not the Bard

This one has a long span, as befits a proper traditional tune rather than a fashionable Victorian party piece. The alternative title “Blame not the Bard” is the title and first line of Thomas Moore’s song.

This tune is widespread in the tradition, with a number of different traditional lyrics sung to it, and also played an instrumental air under any of these different names.

Edward Bunting made a live transcription of Kitty Tyrrell in the 1790s, from a harper, perhaps Hugh Higgins, which I wrote up briefly here. I would imagine our 19th century harpers got it in the direct harp lineage back through Arthur O’Neill to the 18th century Irish harpers.

‘S a mhuirnín dílis, Eibhlín óg

Also in joint 4th place with 9 harpers listed is this curious popular song, more usually anglicised as Savourneen Deelish, Eileen Oge.

Aug 1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, under the title Eirinn go brath – Ireland for ever

1835 Wall, under the title Erin Go Bragh

3 Mar 1838 Byrne, under the title Savourna

15 Nov 1842 McCurley, under the title The Exile of Erin

17 Feb 1844 anon, under the title Sovournian Deelish

19 Aug 1857 Gerharty, under the title Savourneen Deelish

Now I don’t know who Gerharty is, and so it is possible he is a classical harpist and we should strike him from our lists. But I’ll give him the benefit of the doubt for now, since he is in a context where we often find traditional harpers at that time. You’ll also see the variant titles – I think these all refer to the same tune but I am not entirely sure. Part of my justification for combining these titles is traditionary information from Arthur O’Neill. When he was dictating his Memoirs, in about 1808, he describes playing the restored Brian Boru harp in the streets of Limerick as a young man, perhaps in the 1760s:

The first tune that I happened to Strike on, was the Tune of “Elleen Oge”, now generally called “Savourneen Dheelish. and Erin Go Brah,”

(Arthur O’Neill, Memoirs, QUB SC MS4.46.020)

I discussed this all a bit on my writeup of a different tune in the Bunting manuscripts with a similar title. The only traditional performance of this tune I can find for you is by Leo Rowsome.

An Chúilfhionn

The fine old harp air of The Coolin is also in joint 4th place, with nine different harpers listed:

1835 Wall, under the title of The Coolun

1838 Byrne, under the title of Coolun (also at least five other later tune-lists)

1842 McCurley, under the title of The Cooleen

1844 anon, under the title of The Coolin

1851 O Connor and Bell, under the title of harp solo: The Coolin (als Bell in a solo concert)

1864 Fitzgerald, under the title of The Coolin

1876 Murney, under the title of The Coulin

I don’t know who FitzGerald is; he is mentioned playing to illustrate a lecture, and he may be a classical harpist. But I’m giving him the benefit of the doubt.

The Coolin doesn’t appear in our lists before 1835, but after that it appears a lot – Byrne especially often includes it in his concert announcements. Its also one of the very last tunes mentioned, in an anecdote about Murney’s student days in the late 1830s, dictated by George Jackson in 1908. This is an interesting one because while there is a Tom Moore song to this air, none of our harpers are using his title for it.

The Coolin is still well known as an instrumental tune in the tradition. This is my favourite recording of a traditional musician playing it:

We have a lot of mentions of The Coolin in the 18th century harp tradition; I discuss these in my recent writeup.

God Save the Queen

Finally, in joint 4th place, with nine different harpers listed, is the National Anthem.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, performing for George IV, under the title Go mbeanaigh Dia an Righ – God save our King

1840 Messrs O’Connor of Limerick, under the title God Save the Queen

1848 anon, under the title God Save the Queen

1855 Bell, under the title The National Anthem

1858 Byrne, under the title God Save the Queen

From 1800 until 1919, the whole of Ireland was an integral part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Whatever the personal political opinions of individual harpers, this was the society and scene they were working in, and our tune lists mostly represent their public, commercial efforts to make a living at their craft. Patrick Byrne made a great name for himself as the Royal harper, playing for Queen Victoria at Balmoral. And of course the four in 1821 were performing for George IV on his royal visit to Ireland.

I don’t know who Messrs O’Connor of Limerick are. We have Mr O’Connor who was touring with other traditional Irish harpers; maybe there is an error in the report and it should say (for example) Messrs O’Connor and Bell, who are listed as playing the national anthem in their concert in Wexford in 1851. I don’t know. We also have one anonymous harper. So this tune could be less popular than my list suggests.

I also note that 1858 is the latest date we have for it that I know of; I think that later in the 19th century the traditional Irish harpers become more associated with Irish nationalist political activism, playing for Repeal processions, and temperance and home rule meetings.

I have to say this is not a tune I have ever heard being performed as part of a Historical Irish Harp concert programme.

Bumpers, Squire Jones

I have eight harpers listed who played the Carolan tune, Bumpers Squire Jones

1809 Miss O’Reilly and two other pupils at the Belfast Harp Society school, under the title Bumper Squire Jones

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, under the title Cupan faoi Iones – Bumper Squire Jones

1855 Bell, under the title Bumper Squire Jones

This seems to be an early tune – it is possible that Bridget O’Reilly’s two classmates were amongst the four who played for George IV in 1821, which would reduce the score of this tune.

This tune is well-attested in the 18th century Irish harp tradition and so our harpers must have got it in direct transmission through Arthur O’Neill. There’s a version in Bunting’s manuscripts, but it doesn’t look like a live harp transcription to me. If you check my Old Irish Harp Transcriptions Project Tune List you can see that Bunting claims he got the tune from harpers Charles Byrne and Arthur O’Neill. He published it in 1809 (p.26).

I’m not sure it survived in the living tradition into the 20th century though; it looks to me like it might be one of the tunes that was reconstructed from the published keyboard arrangements; Paddy Moloney did a lot of work with Sean O Riada and the Chieftains to revive tunes like this and to put them back into the tradition from the written collections.

Planxty Plunkett

Eight harpers are also listed for Planxty Plunkett

1809 Miss O’Reilly and two other pupils at the Belfast Harp Society school, under the title Planxty Plunket

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, playing for George IV, under the title Plancstaigh Plaincead – Planxty Plunkett

1835 Wall, under the title Planxty Plunkett

Again this seems a tune played in the early part of the 19th century but not later.

Actually I have a problem here, I an not quite sure what this tune might be. There are two Carolan tunes that are possible contenders, the most likely might be DOSC 152, Planxty Plunkett which we know from Neale (1724) and Mulholland (1810). But it is also possible it is DOSC 151 James Plunkett / Gra na mban og, which Bunting made a live transcription of apparently from a harper. Given that we might presume our harpers got the tune in the living harp tradition, 151 seems like it might be more likely, but I don’t know. It’s the same tune as some versions of Moll Dubh an Gleanna:

Brian Boru’s March

I have found Brian Boru’s march listed against 8 different traditional Irish harpers.

1844 Fraser, under the title Brian Boru’s March

1851 O Connor and Bell, under the title harp duet: Brian Boroughme

1856 Hanna, under the title Brian Borombhe’s March

1857 Byrne, under the title The battle of Clontarf

1861 Hardy, under the title Brian Boroihme’s march

1863 anon, under the title Brian Boroihme

This title actually appears loads of times; I have another concert from O’Connor and Bell, and another from just Bell; and as for Byrne, I have at least 6 other concert announcements including this tune, also under the usual Brian Boru title. We also have the famous description from The Emerald (New York, 19 Sep 1868, vol 2 no 33 p108-9) describing Byrne’s performance of this piece in detail.

I wonder if this tune came into the harp tradition in the early 1800s. I am not finding any reference to it in the repertory of the 18th century harpers; but it has been closely associated with harping in Ireland ever since, being picked up very early on by the revival classical-style harping tradition from the 1890s on, even before the inherited tradition had come to an end. Treasa Ní Chormaic, a prominent classical-style revival harpist in the late 19th and early 20th century, “played at the St. Patrick’s Day concert at the Queen’s Hall in London and literally brought the house down with her rendering of Brian Boru’s March” (Sheila Larchet Cuthbert, The Irish Harp Book, p.237).

Carolan’s Receipt

Carolan’s Reciept or Dr John Stafford (DOSC 161) has 7 harpers listed for it.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, performing for George IV, under the title Plancstaigh Staford – Carolan’s Receipt

1835 Wall, under the title Carolan’s Receipt

1855 Bell, under the title Carolan’s Receipt

11 Oct 1856 Byrne, under the title The Receipt (Carolan)

Bunting published this tune in 1840 p.54; he said he got it form the harper Black but I haven’t found a live transcription from a traditional harper. I’m also not finding a traditional performance of Carolan’s Receipt to show you – it looks like it disappeared from the tradition, to be reintroduced via classical-style harp re-discovery.

Garryowen

Garryowen also appears with seven harpers named as playing it.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin under the title Garuigh eoghain – Garune

1835 Wall, under the title Garry Owen

1851 O Connor and Bell, under the title Harp duet: Garryowen (varied)

I don’t know much about this tune, or where it comes from. It became best known as a military tune in the 19th century, and is notorious for being used by General Custer’s regiment when he was massacring native Americans. You can listen to a wax cylinder performance by Patsy Touhey at ITMA.

Planxty Connor

Planxty Connor has seven names as well.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, performing for George IV, under the title Plancstaigh Conchobhar – Planxty Connor

1835 Wall, under the title Planxty Connor

1844 Halpin & Dowdall, under the title Planxty Connor

Planxty John O’Connor is a great Carolan song and harp tune (DOSC 114). But it seems to have dropped out of the living tradition; I haven’t seen a traditional performance, only those obviously taking it from the keyboard arrangements published in the 19th century. Bunting published it in 1809 (p13), and he says he got it from the harpers Hempson, and Mooney, but I don’t find a live harp transcription and he may have copied it from a book. He did take down a traditional song air from the piper Blind Billy O’Malley in 1802, which has a somewhat different shape, but he never published this. I think Lynch got the words from O’Malley on the same trip but I have never seen them matched up together.

I suppose it is possible that the harpers were playing Planxty Charles O’Connor (DOSC 125) which seems to me to be actually quite similar.

And just to cover my back I should say that Donal O’Sullivan lists a total of 11 different O’Connor tunes attributed to Carolan…

Coillte Glasa a’ Triúcha

This great old harp tune and sean-nos song has 7 names against it, but only from two events.

1809 Miss O’Reilly and two other pupils at the Belfast Harp Society school, under the title The Green Wood Tringha

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, performing for George IV, under the title Cuilte Glas an Truach – The green Woods of Truach

We can see that these are both early; these are all first generation students of Arthur O’Neil.

Bunting published a classical piano arrangement of Coillte Glasa a’ Triúcha in 1809 (p42); he says he got it from Arthur O’Neill but I haven’t seen a live transcription notation from a harper. I also haven’t heard a traditional performance of that tune or the Irish lyric, except those done by reconstruction from the keyboard versions. There is a traditional song in English but it has a different tune; I don’t know if this might be what the harpers were playing. Probably not.

Cailin Deas Crúite na mBó

The Pretty Girl Milking the Cow is a very nice sean nós song. Seven of our old harpers are said to have had this tune.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, playing for George IV, under the title Cailin deas cuirte amhuil na mbo – The affable fair maid

1835 Wall, under the title The Valley lay smiling before me

1854 O’Connor, under the title song: Terence and Cathleen

1864 Fitzgerald, under the title The Colleen Dhas in A minor

This is the same Fitzgerald mentioned above, who played the Coolin and Cailin Deas to illustrate a lecture. I don’t know who he was; he may have been a classical harpist. He plays Cailin Deas in A minor afther the Coolin (presumably G major) to show how you can play indifferent keys without re-tuning the harp. I’m giving him the benefit of the doubt for now but he might be for the chop if I find out more.

Terence’s Farewell to Kathleen is a song lyric written to this tune by Lady Dufferin; O’Connor is obviously singing Lady Dufferin’s words. The Valley lay smiling before me is Tom Moore’s song to this tune

Bunting published a version of Cailin Deas Crúite na mBó in 1797 (no.54) and 1809 (p.59). He tells us he got it from Arthur O’Neill. Perhaps he did. In which case our harpers may have got their harp setting in direct transmission from O’Neill.

The nicest traditional recording for you to listen to might be Patsy Touhey’s wax cylinder

Planxty Power

We have six names against this title, at two events:

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, performing for George IV, under the title Plancstuigh poghar – Planxty le poer

1844 Dowdall & Halpin, under the title Planxty Power

I don’t know what tune this might be; it could be any of DOSC 155 Fanny Power, DOSC 153 David Power, or even DOSC 154 Carolan’s Concerto. More research on titles is needed here.

Tigherna Maigh Eo

We have the same six names against Lord Mayo.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, under the title Tighearna Mhaigheogh – Lord Mayo

1844 Dowdall & Halpin, under the title of The Lord of Mayo

Lord Mayo is one of the big 18th century harp tunes and sean nós songs. I’m not sure if the song continued in the tradition into the 20th century, but the tune seems to have transformed into a march:

Molly MacAlpine

Another tune with six harpers’ names against it, though from three different events this time, is Molly MacAlpine

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, playing for George IV, under the title Mara ni Calpin – Mary Mac Calpin

1842 McCurley, under the title Bryan the Brave

1844 Fraser, under the title Remember the Glories of Brian the Brave

Molly MacAlpine is said to have been composed by one of the Connellan brothers, it is a big sean nós song and traditional harp tune. Bunting published the tune in 1797 (no.44) and he later says he got it from the harper Catherine Martin from Virginia, but I think he is lying or exaggerating because he obviously copied it straight from the Neal book (1724). Brian the Brave is Tom Moore’s song written to Bunting’s piano tune.

In any case the tune went into the fiddle and pipes and dance tradition under a corrupted English title “Poll Halfpenny” or similar. I am very interested to listen to Patsy Touhey’s wax cylinder recording, even though he has messed up the modal structure of the tune on the pipes.

Sprig of Shillelagh

Six harpers are listed against this tune.

1821 Rennie, Mac Monaghal, McBride, McLoughlin, playing for the King, under the title Sileligh – Shileligh

1835 Wall, under the title Sprig of Shillelagh

1844 Fraser, under the title Sprig of Shilelah

This is a traditional set-dance tune usually played on fiddle or pipes, and it is also a military march:

I’m kind of interested in how these multi-purpose tunes are being played by the harpers. As well as their patrons often having Anglo/military connections, I have seen references to harpers sharing their concert platforms with military bands.

The Meeting of the Waters

Five harpers are listed as playing the Meeting of the Waters.

1835 Wall, under the title The Meeting of the Waters

1842 McCurley, under the title Sweet Vale of Avoca

1844 Fraser, under the title Meeting of the Waters

1854 Byrne, under the title The meeting of the Waters also in 3 or 4 later concert announcements.

1855 Bell, under the title The meeting of the Waters

The Tom Moore song The Meeting of the Waters is said to be set to a traditional tune “The old head of Dennis” but I haven’t followed this up. In any case, all of our harpers are using the Moore song title. Maybe they are singing Moore’s words as well.

The Rising of the Lark

We have five harpers who played the Rising of the Lark:

1835 Wall, under the title Rising of the Lark

1842 McCurley, under the title The Rising of the Lark with variations

1844 Fraser and Entegerth, under the title Rising of the Lark

1851 Bell, under the title Harp solo: The Rising of the Lark

I’m not entirely sure about this one. There is a Welsh harp tune, Codiad yr Hedydd, published by Edward Jones, in Musical and Poetical Relicks of the Welsh Bards (1784), and this may be it.

Nansi Richards (1888 – 1979) was a key tradition bearer in continuing the inherited tradition of Welsh harp playing from the 19th century into the 20th. I don’t think there was anyone like this in Ireland, which is why there were no traditional Irish harpists playing in the inherited tradition after 1910. I think traditional Welsh harp style on gut-strung triple harp is very different to the old Irish harp style on metal wire strings, but I’m sure the audiences and our harpers would have heard this kind of thing played by Welsh harpers touring in Dublin and further afield.

The Minstrel Boy

The Minstrel Boy has five harpers listed as playing it.

1835 Wall, under the title The Minstrel Boy

1844 Halpin & Dowdall, under the title The Minstrel Boy

1854 Byrne, under the title The Minstrel Boy

1876 Murney, under the title Minstrel Boy

The Minstrel Boy is Tom Moore’s song, supposedly set to the traditional tune “The Moreen” but just like with the Meeting of the Waters, everyone knows it by Tom Moore’s song title. It’s a great tune and I’m sure it went down well with the audiences! I’m thinking that tunes like this have spread so far beyond Irish traditional music that they are not really played in the tradition at all.

Again the military connection… this is curious.

The Harmonious Blacksmith

Five harpers list The Harmonious Blacksmith in their repertory lists:

[c.1837] Murney, under the title The Harmonious Blacksmith

1842 McCurley, under the title The Harmonious Blacksmith

1844 Fraser and Entegerth, under the title Harmonious Blacksmith

1855 Bell, under the title Handel’s Musical Blacksmith

I have put Murney with a date c.1837, because that is when he finished studying under Rennie. The information comes from George Jackson’s dictation in 1908.

The Harmonious Blacksmith is an air and variations from Handel’s Suite No. 5 in E major, published in 1720. The tune only seems to have become popular in this extracted form from the 1820s.

That will do for now! I think we have looked at the most popular 24 tunes. There are loads more. We can consider them another day. I think that the tunes that were less popular, with only one or two harpers playing them, might tell us more about that individual’s particular interests, or context. For example, Pat Byrne has a lot of Scottish tunes, which would make sense for him touring in Scotland and playing at the houses of the Scottish aristocracy. O’Connor seems to be a bit of a showman, and has some novelty acts. Wall in Philadelphia has popular American tunes.

But these 24 most popular tunes played in public by the old harpers gives us an insight into the state of the old Irish harp tradition in the 19th century. We could do a lot of work to collate this list against both the repertory of the 18th century harpers as noted by Bunting, and the tunes that remained alive in the tradition through into the 20th century and to the present day.

If you want to explore my full list, you can view or download my 19th century Irish harpers tune lists spreadsheet.

Any questions or comments, email me or leave a message in the comments below. This is very much a new work-in-progress. I hope to find more tune lists and more information about the tunes in the future. I am only just beginning to look at the traditional Irish harpers through the 19th century!

Many thanks to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for helping to provide the equipment used for these posts, and also for supporting the writing of these blog posts.

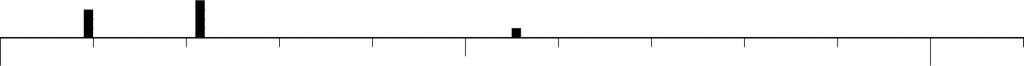

Here’s a chart which shows how small our information sample is. The blue bar for each harper shows the number of different tunes listed for them in the tune-lists. You can see that over half of the 19th century harpers have no tunes attributed to them at all.

I think it is clear that while these newspaper tune lists are fascinating, they only show us the commercical end of the activities of some of the harpers. I don’t know how we can find out what the others were doing and what was the real core of the repertory, rather than what was commercially successful.

I think that the tune of “The Meeting of the Waters” is a version of Buachaill ón Éirne.