One of the problems with trying to trace these harpers in the 19th century records, is when there are multiple variant spellings of names. Sometimes it becomes unclear if we are dealing with two different people or not. This is a big problem if we are trying to reconstruct the life story of an individual.

Sometimes there is direct evidence that helps us to divide one name into two people (e.g. concerts by Mr. Rennie after the death of Valentine Rennie). Other times the record-keeping helps us to be sure that two names belong to one person (Hamilton Graham / Hamilton Gillespie in the Harp Society minutes, 1820-21). But often we just have to guess based on circumstantial evidence or hints.

We have references to James MacMonagal, and also to James McMolaghan. I really don’t know if they are two different people, or two different versions of the same name. This post is to draw together the references we have so far, and then to be a place where further references can be added in the future.

Early years and education

We first meet James McMolaghan when he was a scholar in the Irish Harp Society in Belfast. The minutes for the meeting of 2nd January 1810 include the complete list of 12 scholars then studying full-time in the Society school, under the teacher Arthur O’Neil.

James McMolaghan of Lifford County Donegall aged 13. Entd Octr 1809 Recommended by Mr. Mitchell of Breis Bridge one of our Committee.

Belfast, Linen Hall Library, Beath Collection, Box 5.1

Lifford is a town right on the border between Donegal and Tyrone. If James was 13 at the beginning of January 1810, he must have been born in 1796.

I don’t think we have any more references to him at the school, but we can guess what his life there was like from the general information about the Irish Harp Society at that time. We know that Arthur O’Neil and nine of the pupils lived in the Harp Society House; the pupils were all blind or partially-sighted. I think James McMolaghan might have been the last of these pupils to join, because all the other 8 boarding pupils have earlier joining dates. There were also three day pupils who lived in Belfast, but we don’t have their joining dates. I also have a feeling that a couple more pupils may have joined in June 1810, after William Gorman and James O’Neil were dismissed as “incapable”.

I think there was a great shortage of harps at this time. The pupils would not have had their own; the Harp Society had purchased a few harps (perhaps as few as three) from Belfast makers; Arthur O’Neil the tutor would have had his own old harp, and I assume Bridget O’Reilly may have had her own since she seems to have been out performing before she joined the school.

I have already written posts about some of James McMolaghan’s other classmates. As well as Bridget O’Reilly and James O’Neil, I have written up Edward McBride, Abraham Wilkinson and Hugh Dornan. Some of these posts include more information about the running of the school.

Leaving the School

We don’t really have much information about the end of the Society school. In theory, each of the pupils was meant to be examined by the Committee, and when they had reached a professional standard, they were to be discharged with a certificate and a harp, so that they could go off and make their livings as professional harpers. What seems to have actually happened is that the Society ran out of money and gradually dribbled to a stop.

In 1812 all the students were sent away from Belfast, basically to make their own livings. They may have been given their certificates at this point, but I don’t think there were enough harps for them to have been given one each. They may have come back to Belfast to perform together for fundraising events which were organised with the intention of keeping the Society going through 1812 and into the beginning of 1813. There is a reference to there being twelve finished harpers at a benefit concert in the Belfast Theatre the end of 1812 (Irish Harp Society, QUB SC MS4.37.10) though two of the original 12 had been dismissed as “incapable”, so presumably two more had entered. There were plans for a big fundraising effort in 1813 but nothing seems to have come of it, until the money arrived from India in 1818 which led to the re-starting of teaching in 1820. But that’s for another story.

Touring in 1812

We have an account from 1812 which tells us in quite a lot of detail what James McMolaghan was doing that year. It is printed in the 1813 Annual Report of the Hibernian Society for the Diffusion of Religious Knowledge, a strongly evangelical religious educational organisation, which ran church schools for young people, and is in the form of a couple of letters “from an Agent of the Society”. Unfortunately we are not told who their Agent was, or where his school was, and the names of the other people in the letter are redacted. Even our harper’s name is partly redacted, but when we read about “James M‘M______”, a harper from the Belfast Harp Society, touring in 1812, aged about 17, then I think we must be right to identify this as the same James McMolaghan from the minute book.

The letters were written in the autumn of 1812, and read on two levels. The surface level is the religious attitudes, but we can read between the lines to get a pretty good idea of what our harper James was up to that year and how it fits into his life story. James is the younger of the two harpers. I do not know who the older one was.

(No. 3.)

The Seventh Annual Report of the Hibernian Society, For the Diffusion of Religious Knowledge in Ireland (London, 1813) p. 28-31

From the Same. Dated September 29, 1812

Last spring two young men, with impediments in their sight, called at my house. They were harpers, educated to that profession by the Belfast Harp Society, which has been formed with a view to revive our national instrument. They were both rigid Catholics, full of ignorance and prejudice. The day after their arrival, the youngest of them, a mild pleasing young man, was attacked with an alarming inflammation in his stomach. His companion, the day after, fearing immediate death would be the issue, requested of me the liberty to call on the priest, to give him the rites of his church. I told him it was a step I could not sanction, though as I looked on all interference with the liberties, even of a deluded judgment, to be a species of persecution, I would not prevent the priest from coming, if the poor young man persisted in desiring it, after I had spoken to him. I spent some time conversing with the afflicted person, as he was able to bear it. He listened with great attention, and the issue was, that he seemed not to be anxious for the priest. Shortly after, it pleased God to restore him, though he was so reduced by the violence of the distemper that he could not leave my house for three weeks, during which time his companion remained with him. Hearing every day repeatedly on the nature and evidence of salvation, their attention was excited; they both spent much of their time in our school; and before their departure they entertained very strong doubts on the subject of their religion. They left this place each of them furnished with a Testament, in order that they might have it read to them, when opportunity offered. Some time after this they parted. The eldest returned to Belfast, I trust, with a witness in his conscience which he will not easily silence; and the youngest James M‘M_______ proceeded to the counties of Roscommon and Galway. In the latter place he was in the zenith of popery; and here, all that he witnessed, instead of removing his doubts, multiplied and confirmed them. Such were the ignorance and bigotry of the poor in this country, as to prevent their giving him a draught of water as he passed, because as he could not speak Irish, they deemed him a heretic; even among the great, he beheld nothing but gross superstition, deep ignorance, and great disaffection. Passing from the county of Galway, he came to W________, and in the family of Mr. C________ had again the much desired opportunity of having the Scriptures read to him by Mrs. C_______. Hearing the character of Mr. G______, he went to church, and was astonished, and pleased, to hear from him sentiments similar to those he had heard here. He then resolved to pay us another visit, and arrived here about three weeks ago. His progress, since his arrival, has been truly astonishing. He is alive to nothing but the gospel. From morning till night he is occupied in committing portions of Scripture to memory; C______, before breakfast, and after the family retire to rest, is employed in reading, repeating, and conversing with him on the subject. D_______ and C_______, whom he soon discovered to be suitable mates for him, read to him during the day; and some of my family assist him in the evening, after school-hours. His harp lies neglected, and he sighs for some way of support more congenial to a christian life; for although he has much joy indeed from his discovery of divine truth, the prospect before him, as to getting through the world, causes him many heavy hours. Conversing on that subject he said,

“I must go to America, or to England. I cannot stay in this kingdom. The Catholic gentry are the principal patrons of the Irish harp; to them I have been taught to look for support; and I have experienced their bounty: but my present views cut off all my expectations from that quarter. Each of them has his chaplain; some from devotion, but most, because it is respectable to keep one. In those families, each morning is ushered in by the celebration of mass, and the assistance of the harp is esteemed the revival of a part of the splendor and solemnity of their religion: but I dare not now do it; I could no longer countenance such an abomination.”

I have dwelt the longer on the case of this young man, about 17, as I think it truly extraordinary. He has a great zeal for the conversion of others; and those who have been brought from under the delusions of popery by the gospel are his delight. He has good natural abilities, and I think, by a skilful surgical operation, he might get the use of his sight, or, even in the present state of it, might be an instrument of great usefulness. I have encouraged him to remain here, and now submit his case to the Society.

(No. 4.)

From the same. Dated Oct 27, 1812.

… [brief mention of other schools including Irish translations of the bible] …

In my last I mentioned the case of James the harper, so mercifully brought to the knowledge of our Lord, and the pleasing hopes I entertained of the conversion of C_______; since which I am confirmed more and more in the opinion I then gave of both. Indeed, for the time, I scarcely ever witnessed such maturity of judgment, as is manifest in the young harper; and from the progress he has made, and continues to make, and his insatiable thirst for divine knowledge, I cannot but think that he is designed for extensive usefulness…

… [more about C_____.] …

(No. 5)

From the same. Dated November 23, 1812.

… [comments on converting Catholics, the mass of the people] …

… I find myself particularly interested in the case of James, the young harper; believing that, if spared, our Lord intends him for great usefulness. His want of sight, and consequently being unable to read, may appear to disqualify him for serving in the gospel: but yet, I have never met an individual, however qualified, that has, for the time, made such a proficiency in the knowledge of the Word of God; not merely in committing it to memory, but in the ability to understand, and rightly to apply it. He can already repeat near fifty chapters, and those of his own selection; among which are Isaiah liii. and liv., Ezekiel xxxvii. and xlvii., John xv. xvi. and xvii., the first ten chapters of Romans, Ephesians i. and ii., Galatians i. iii. and iv., 1 Corinthians i. and ii., 1 Thessalonians iii. and iv., a part of the Hebrews; from chap. ix. of which he overturns the doctrine of transubstantiation; the whole of the three epistles of John and that of Jude. His thirst for spiritual knowledge continues insatiable, and his application is only limited by the opportunity of getting others to read to him. His abhorrence of error is in proportion to his love of the truth, which indeed is great: nor is his conscientious regard to its effects less conspicuous; which I have witnessed, not only with respect to his own conduct, but his watchful attention to that of C______, and others.

As usual we could write a thesis on this from any number of different viewpoints but in this post we are interested in the music and working lives of the harpers. It is a shame we have no hint of who the other harper was. We can check my timeline to see that most of James’s classmates were older than he was, so it could have been any of them.

We are told that James did not speak Irish; the episode when James is travelling in County Galway and the people treat him badly because of this is very interesting. We rarely have any direct statement about whether these 19th century harpers can speak Irish or not. The language was in sharp decline through the 19th century, and many of the harpers came from north-east Ulster where the language was weakest at that time (see Aidan Doyle, A History of the Irish Language, Oxford 2015).

I think we can sketch out a story of what James McMolaghan was up to over the course of the year. I think “Last Spring” refers to the spring of 1812, and so we can see the two lads presumably leaving the Harp Society House in Belfast in early 1812, and heading out on the road going from house to house looking to be put up and earn a bit of money in exchange for music. Perhaps they were touring together to share a harp, or perhaps just for mutual support and encouragement.

James’s comment in his speech is very revealing about their work; he says that he has been taught to look to the Catholic gentry for employment. Presumably this is from his master Arthur O’Neil; from the beginning, the Harp Society recruited its pupils “of either sex … without distinction of sect or country” (Freemans Journal 16 June 1808 p4), and plenty of our boys are obviously from Protestant backgrounds. I assume that they were taught this from a purely business point of view. I see the Harp Society school education being a bit like a craft apprenticeship, not just teaching the playing techniques and repertory, but preparing the boys in every way so that they were able to walk out the door and make a living as successful professional or “artisan” traditional musicians. So I imagine Arthur O’Neil talking to them about how to get gigs, how to interact with patrons, how to get letters of introduction, how to maintain the harp, and that kind of business skill.

James goes on to say how these Catholic gentry would at this time have wanted to have a harper in the house and to play in their chapel. He says that he has “experienced their bounty” i.e. that he has stayed with some of the Catholic noblemen at their big country houses, and has played for mass at their private chapels. But the fact that the two boys called at this Evangelical house also shows that they were happy to take board, lodgings and work from anyone.

Anyway they arrive at this man’s house some time in the Spring of 1812. James gets very ill but recovers quickly. The two of them stay with our man for three weeks while James recuperates from his sudden and severe illness. Then after three weeks there, they leave together.

At some unspecified point later, the two harpers split up; the older one heads back to Belfast, while James heads West through Counties Roscommon and Galway. On his travels he obviously sees higher-status people, and presumably stays in their houses to entertain them. Then he moves on out of Galway and gets to W_____ (perhaps Westport in County Mayo?) where he spends some time with another family in their home. They also talked religion to him, and he was enthused by it again, and decided to go back to our man’s house.

James arrived back at our man’s house in early September 1812, having spent the whole summer – perhaps June July and August of 1812 – touring out West. He then stayed with our man for about three months, and was still there in late November. We are told that “his harp lies neglected” because he spends all his time in bible study. This was before the invention of “books for the blind” with embossed lettering or Braille patterns; unlike Samuel Patrick or Patrick Byrne, who we know could read by feeling the letters in their books, James was dependent on someone else reading aloud to him.

So what happened next? Did James give up the harp and become an evangelist or missionary? Did he go to an eye-surgeon and have his sight restored? Or was this religious thing a passing phase in his life, and did he leave our man’s house and go back to Belfast and re-join the other harpers and go back to being a traditional musician? Did James return to Belfast for the concert in the Theatre perhaps in December 1812? (I have not found any newspaper adverts for this concert, nor any other mention of it so far apart from the letter reprinted in the Irish Harp Society pamphlet).

I have no further references to James McMolaghan… Unless, of course, the Secretary of the Irish Harp Society in Belfast had simply mis-spelled the name in the minutes of the 2nd Jan 1810 meeting.

James MacMonagal

I really don’t know whether McMolaghan is variant or mis-spelling of MacMonagal, or not. It is possible that James MacMonagal is a different harper. At the moment I don’t know. But let us carry on and see what we think.

Playing for the King

James MacMonagal played for King George IV during the royal visit to Ireland in 1821. We have a little printed programme for the performance, which names him.

VALENTINE REANNEY, JAMES MAC MONAGAL,

EDWD MAC BRIDE AND JOHN MAC LOGHLIN,

Irish Harpers.

This tune list is very interesting and I have discussed some of the tunes on my tune list post. But what can we say about the harpers?

The King had a busy itinerary in the summer of 1821, and harpers were provided for two consecutive days in Dublin.

On Thursday the 23rd August, the Corporation of Dublin gave the “City Banquet” to the King, in a magnificent room specially erected for the occasion. The decorations were in an elegant and classic style. The musical arrangements, in which the celebrated Miss Stephens, afterwards the Countess of Essex, was one of the vocalists, presented an interesting national peculiarity in the performance of a number of Irish harpers, two of whom were sent by the Lord of Shane’s Castle, dressed in the ancient costume of the O’Neills, made first familiar to the English reader by the chronicler of the famous visit of Shane O’Neill to Queen Elizabeth.

Hubert Burke, Ireland Sixty Years Ago, London, 1885 p20

I think the chronicler was William Camden, so perhaps the harpers’ costume was inspired by his description:

… who had their heads naked, and curled haire hanging on their shoulders, yellow shirts, as if they had been died with Saffron or steeped in urine, wide sleeves, short Cassocks, and rough hairy Clokes…

Annales, the true and Royall history of the famous Empresse Elizabeth… (Benjamin Fisher, London, 1625) p90

Or perhaps they were just wearing the familiar “bardic” costume of a long robe like we see in Patrick Byrne’s blanket photos.

The next day there were only three harpers:

On Friday, the 24th, the king visited the Royal Dublin Society, at Leinster House, the lawn of which was covered with beautiful tents, ranged in semi-circular form round a magnificent marquee, where his majesty was entertained. Three harpers, robed in the antique garb of Irish minstrels, were stationed at the entrance of the tent. He was received by the members, about one hundred and fifty in number, all decorated with the insignia of welcome. The price of admission to this féte champétre was five guineas for a member and two ladies.

Cassel’s illustrated history of England… vol III (being the seventh volume of the entire history) from the accession of George IV to the Irish famine, 1847 (London, 1863) p51

Five guineas is perhaps the equivalent of a couple of grand nowadays, and 150 people each paid that to get in, so I hope the boys were being well paid for this costumed gig. We have a description of the costume worn by these three harpers:

Three Irish harpers, dressed in the ancient costume of their order, attended with their harps. They wore wreaths of laurel, and velvet robes, which gave them an antique appearance. But they did not favour us with many exhibitions of their skill. Their harps seemed to be out of order.

London Morning Herald, Tue 28 Aug 1821 p1

No surprise really that the harps were out of order, playing outside in the scorching August sun.

We have the names of the four harpers who played on the Thursday evening (McMonagal, MacLoughlin, McBride and Rennie). But I don’t think at this stage it is possible to work out which two of the harpers came from Shane’s Castle, and which three played in the tent the next day. In my post about Edward McBride, I pointed out how in 1821, he was working in Belfast, as tutor to the Irish Harp Society school on Cromac Street. Valentine Rennie seems to have been working in Dublin at this time, and before 1820, the two of them seem to have had a history of working together right back to their school days. Another connection between McBride and Rennie comes from traditionary information written down from the dictation of the harper and tradition-bearer Patrick Byrne in about 1849, who says that Rennie played a harp made by McBride’s father:

Edward McBride, Vallentine Rainnie and James Mc Mannigal were the three who played before George the 4th in Dublin.

…Rainie’s Harp was made by James Mc Bride, a wheelwright near Omagh… It was the harp Rainy play’d upon before Georg the 4th…

H. G. Farmer, ‘Some notes on the Irish Harp’, Music & Letters XXIV April 1943 p104

Again, only three… Are these the three who played outside on the Friday? Or did Byrne not know, or forget about, John MacLoughlin?

Anyway I think it is possible that MacMonagal and MacLoughlin were working for Viscount O’Neill at Shane’s Castle. But at present this is just speculation.

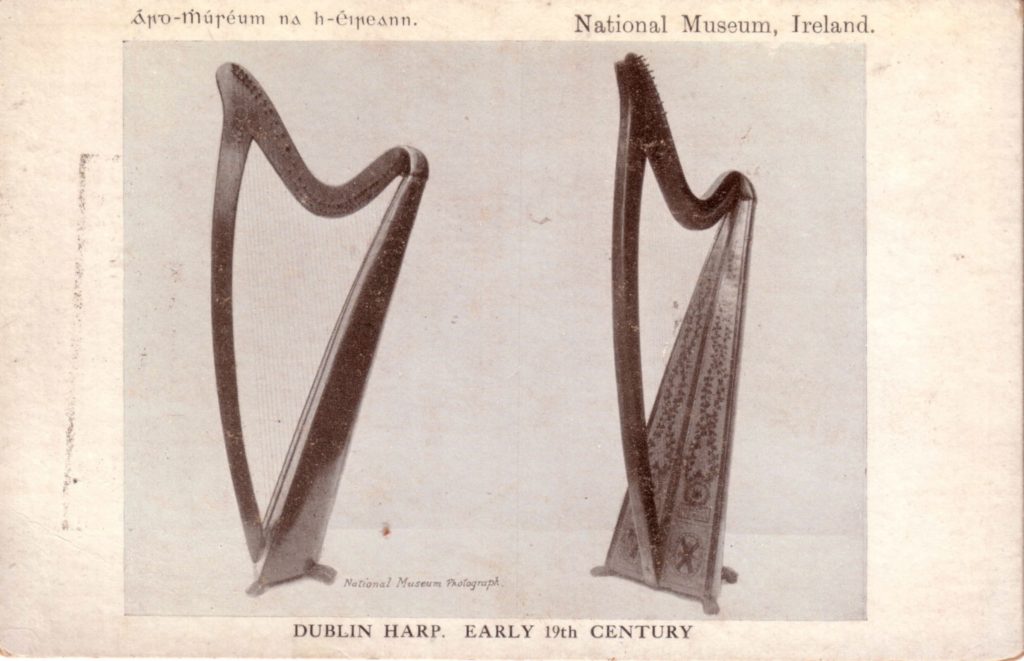

Nancy Hurrell (The Egan Irish Harps (2019) p.154-7) has suggested that the harp illustrated below may have been made in 1821 by John Egan, for Viscount O’Neill, and so it may have been played before the king by one of our harpers. If Rennie was playing the John McBride harp, perhaps Edward also played a harp made by his father; and so perhaps we can speculate that MacMonagal or MacLoughlin might have played this brand new Egan harp. Perhaps Egan made two similar harps for Viscount O’Neill, so that MacLoughlin and MacMonagal could have one each, and only this one survives. Perhaps this is all completely wrong.

Conclusion

I swing back and forth, sometimes thinking that the two names are different enough that they must be two people, and other times thinking that the Secretary could easily have mis-written “McMolaghan” into the minute book.

We only have four written attestations of the name(s) of our harper(s):

- “James McMolaghan of Lifford” (Irish Harp Society minute book, 2 Jan 1810)

- “James M‘M________” (anonymous letter 29 Sep 1812)

- “James Mac Monagal” (programme, 23 August 1821)

- “James Mc Mannigal” (Info from Byrne, John Bell’s notebook, 1849)

As you can see No.2 is kind of useless because of how it is redacted. No. 4 is not trustworthy for its spelling since John Bell was writing from oral dictation and his spelling of names is pretty wayward I think. Anyway it is clearly a phonetical rendering of No. 3.

McMonagle seems to be a name which used to be concentrated in County Donegal. You can see interesting distribution maps from the 1901 and 1911 censuses online by Barry Griffin. You can see that Lifford (on the Donegal – Tyrone border) is in an area where there were a fair number of McMonagles in 1901.

Molaghan (without the Mac) seems to be much less common, and mostly in Leitrim and Longford and a few in Antrim (Barry Griffin map). However I am not finding any information at all about McMolaghan as a surname.

Simon, you mentioned the difficulties with various spellings of MacMonagal. Many seem to have emigrated to Australia in the 19th century. I have come across several here. The most common spelling here is Monagle. By way of trivia, it plagues many Irish names here. My wife is a MacGillicuddy. Various branches of the same family here and in New Zealand spell their name three different ways. I have observed a similar thing with most of my Irish forebears. I suspect illiteracy of the immigrants was a key factor. Sorry, a little off the topic, but I couldn’t resist the comment.

Thanks John. Of course in the case of these blind boys, they were saying their name to someone else who was writing it down however they saw fit. Another and more fundamental source of crazy spelling variants.