Walker was an amateur self-taught player of the traditional wire-strung Irish harp in the mid 19th century. This post is to draw together references to him and to try and say something useful.

Our main source of information is the list of Belfast harpers which was written down by the revivalist William Savage, based on information told to him by the harper and tradition-bearer George Jackson in about 1908.

Here is Jackson’s information about Walker:

Walker. Shipbuoy St Sexton in a church Rosemary St

National Museum of Ireland, Arts & Industry Division, Archive file AI.80.019

Belonged to place Call the Rough Fort High Town

made a Harp and played fairly well only played Bass note thumb

and finger had never seen fingering proper. Visited Raineys

school heard the boys play and played for Rainey on all

Working out Walker’s approximate dates

George Jackson had learned to play the traditional wire-strung Irish harp, in the inherited tradition, from Patrick Murney in Belfast probably in the late 1840s or 1850s. Patrick Murney had learned to play from Valentine Rennie in Belfast in the mid 1830s. Rennie had learned from Arthur O’Neil in Belfast in around 1810. Arthur O’Neil had learned from Owen Keenan in County Tyrone in about the 1740s. I don’t know who Owen Keenan learned from.

George Jackson’s information obviously mostly comes from his teacher Patrick Murney, and mostly describes Patrick Murney’s contemporaries, traditional harpers who had learned the harp under Edward McBride, Valentine Rennie and Alex Jackson at the harp school run by the Irish Harp Society. The school was based in Cromac Street from 1820 through to 1838, and then in Talbot Street until 1840 when it was defunded and closed.

I would presume that Walker visited the school when Murney was a pupil, so we can provisionally suggest that this episode may date to the mid 1830s. So we can start to think that Walker may have been born at the end of the 18th century, or in the early 19th century, and may have died perhaps in the mid to late 19th century.

Rough Fort, High Town

Jackson’s information is not entirely clear; perhaps he seems to be saying that Walker was originally from Roughfort, near Hightown. These are both common enough place names all around Ireland, but there is a Roughfort and Hightown fairly close together near to Glengormley, in the countryside north of Belfast.

You can see Roughfort on the 1832 OS map, at the join between Antrim sheet 51 and sheet 56. Hightown is not named on the 1833-1837 sheet 56, but you can see Hightown as a placename on the 1901 revised sheet 51.

Sexton in a church Rosemary St

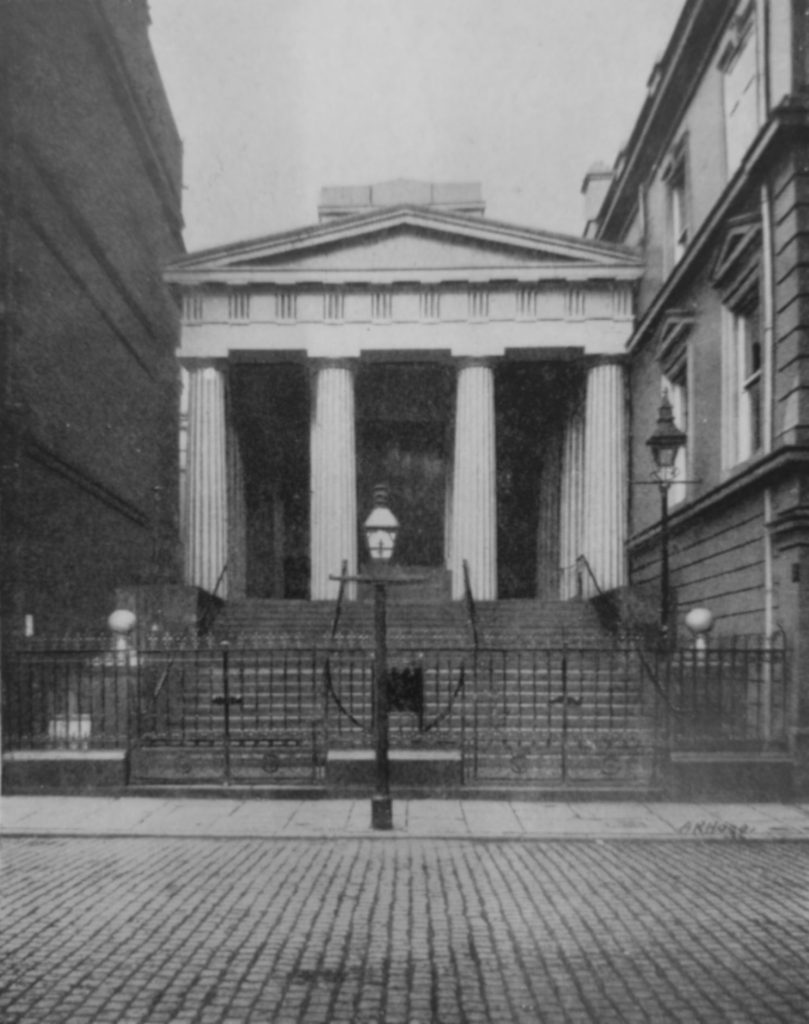

I know of three churches on Rosemary Street, Belfast in the early to mid 19th century. Only one is still there now. You can read a good summary history of the three churches at Belfast Entries.

The First Presbyterian Church originates at the end of the 17th century; it was rebuilt in 1782-3 and remains substantially the same today. I went to visit the church, and Raymond O’Regan showed me a copy of Historic memorials of the first Presbyterian church of Belfast (1887); the list of sextons on p122 does not include Walker, so I think we can be fairly confident that our man Walker was not sexton of the first church.

The second Presbyterian Church was built in 1708 behind the first, because there were too many people in the congregation to all fit into the first. The Second church closed in 1896 when the congregation moved to a new building, All Souls on Elmwood Avenue. The building on Rosemary Street was demolished after the war; the site is now a car park. I have not found a list of sextons for the second church.

The Third Presbyterian Church was built in the 1720s, due to religious arguments and a split within the congregations. It was rebuilt on the same site in 1831. It was damaged by bombing in 1941 and was demolished; the Masonic Hall now stands on the site. The congregation moved to a new building at Rosemary Presbyterian Church on the North Circular Road. I have not found a list of sextons for the third church.

Shipbuoy Street

The 1887 Goad fire insurance map shows Shipbuoy street (here spelled “Shipboy”), running about north-west to south-east, between Nelson Street and Little York Street. This aerial photograph from 1950 shows the same area as the Goad map above. I have labelled the streets:

Every building in this photo has been demolished, but Shipbuoy Street itself is just about still there today.

I checked the Belfast Street Directories, and the only Walker on Shipbuoy Street that I can find is Thomas Walker, from 1850 to 1852. Thomas Walker is listed as a grocer at 48 Nelson Street in the Henderson’s 1850 directory, and he is listed at the same premises in the 1852 Belfast Street Directory. 48 Nelson Street is the north corner of Shipbuoy Street and Nelson Street; we can see on the Goad map that this building has been re-numbered to no.60 Nelson Street by 1887.

I do not know if this may be our man or not. I am not sure how to reconcile George Jackson’s description of Walker being the sexton of one of these churches, and living in or being from Shipbuoy Street. I suppose it is possible that George Jackson’s information is garbled or wrong in some way.

My map shows Roughfort, Hightown and Shipbuoy Street, and the three churches on Rosemary Street.

Fingering proper

George Jackson’s information includes a very interesting and unusual description of Walker’s way of playing the harp:

…played fairly well only played Bass note thumb and finger had never seen fingering proper

I think we can take this as Murney’s assessment of Walker’s playing; if so, it is a fascinating insight into how a traditional harper would think about issues of fingering and playing.

I think we cannot tell exactly what is being described here, on a technical level, but there are clearly two related concepts. One is the description of how Walker played: “only played Bass note thumb and finger”. Perhaps Walker did not use the full bass fingering patterns but only used the thumb and finger of his bass hand; or perhaps the description is more complete, and describes Walker playing in a very simple way, playing a bass note, and then using thumb and finger of his left (treble) hand, in a kind of one-finger-typing way of picking out a tune on the harp.

I think the most significant part of this entire testimony is the statement that Walker “had never seen fingering proper”. Not even that he didn’t use “fingering proper”, but that he had never seen it. This to me is totally clear that Walker had not been taught how to play the harp in the inherited tradition, but that he had made his own harp and then worked out how to play tunes on it himself. Presumably Walker, visiting the school, was fascinated to watch the pupils showing off their skills, and to see the way that the pupils used complex and subtle fingering techniques as well as the interplay of the hands to play the tune and the implied or embedded harmony.

But we can read between the lines, that if Walker did not use and had never seen “fingering proper”, the very strong implication is that Murney and the other pupils did use “fingering proper”. I would take this to mean the system of named fingering techniques used to articulate the tune, and to silence dissonant notes out to create the harmonic structure of the music. We have a garbled presentation of this system in Edward Bunting’s 1840 book (introduction pages 24-27), and Sylvia Crawford has been reconstructing this system by application to the repertory for the past few years, for example in her book.

This kind of one line throwaway comment can be incredibly valuable for us in trying to understand and work out what the traditional harpers in the inherited tradition through the 19th century were actually learning and actually doing. Of course we can never actually know every detail, but as we understand more of the technical and structural aspects of the traditional Irish harp music, comments like this can really help us to define very clearly the parameters that the traditional harpers were working within. And it can also give us a much greater appreciation of and respect for Murney, Jackson, and their contemporaries who were still playing the traditional wire-strung Irish harp in the inherited tradition through into the beginning of the 20th century.