Charles Fanning was a traditional Irish harper in the second half of the 18th century. Because he was still active in 1792, I ought to try and say something about what he was doing during my “Long 19th Century” study period (1792 – 1909).

As usual for these 18th century harpers, we have hardly any records of their lives or activities. All we really have to go on is fragmentary vague anecdotes from later sources.

Arthur O’Neil is as usual our main source of information about Charles Fanning’s life in general, This brief biography is part of a kind of addendum to the neat version of Arthur O’Neil’s autobiography, written c.1808:

Charles Fanning was born in Foxfield in the County of Leitrim in the province of Connaught. His father Loughlin Fanning was a decent farmer and played well on the Harp. Charles was principally instructed by Thady Smith a native of the County of Roscommon & a tolerable performer on the Harp. Charles Fanning in consequence of His performance on the Harp became much respected. He never taught any but merely was an amateur and principally supported himself by the private emoluments arising from his profession. On his first arrival into the County of Tyrone, he got acquainted with a Mrs Bailie of Terrinaskea in that County who played on the Harp very well. Charles married her kitchen maid, for which Mrs. Bailie was greatly disobliged, as she frequently had him at her own Table, and had him introduced to Genteel company. She fell out with him and he was not received as usually. Charley and the wife boxed now and then. He visitted Mrs Bailie generally at 3 months a time in his professional way. His wife was discharged and was generally sneaking after Charley every where. He went from Mrs Bailies to Derry, and got himself introduced to the Bishop who seemed to like him well, otherwise he would not keep him. I Arthur Oneill went to Derry where I met Charley, and when I asked him “how he was” Charley replied “That I might blow a Goose quill thro’ his cheek (meaning he was so poor and thin) and this time he had the wife and one or Two children to support.

Arthur O’Neil, Memoirs (revised version), Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections MS4.14 page 77-79

After he left the Bishop’s he rambled about the nation a while. I next heard he fell in with a Mr. Pratt of Kings Court in the County Cavan, he lived a couple of years there and had a house and Garden and 4 acres of Land and the Grazing of 4 Cows in the Demesne. He had a letter from Mr Pratt that he would give him a Lease of his concern, But on Mr Pratt’s death his brother’s son who was his Heir, refused giving the Lease & turned him out. Charles consulted Counsellor (now Judge) Fox with his Case, who gave an opinion in his favour, and say’d he would make it good. Charles gave Fox the letter, But in consequence of some private influence as he believed he never could get it from him again, and it is generally believed he was betray’d. He then rambled as usual. I saw him often afterwards who told me the above Story about Mr. Fox. I next heard of his being in Belfast in 1792 at the time of the Celebration of the French Revolution where I met him, where he got the Highest prize for his performce on that occasion.

This account was compressed and was printed (with errors) by Edward Bunting in 1840 (intro p.81). Bunting adds that Fanning was born “about 1736”, which he has apparently calculated from a newspaper reference to Fanning being 56 years old in July 1792 (Belfast News Letter Fri 13 Jul 1792 p3, see below)

I think most of Arthur O’Neil’s account deals with the period before 1792 and so we will not pay that much attention to it. However we can clearly see that by 1792, at the start of our study period, Charles Fanning was aged 56 (if we believe the newspaper). He would have been married with probably grown up children. It looks like he was quite poor, making a living by travelling as an itinerant harper by that time.

The mentions of Charles Fanning’s earlier patrons is rather interesting. We have a double connection between Charles Fanning and Dennis Hampson, firstly that Charles Fanning’s father, Loughlin Fanning, had been one of Dennis Hampson’s harp teachers in the early 18th century, and secondly that Charles Fanning had apparently been patronised by Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry (1730-1803) who lived at Downhill House and was Hampson’s main patron.

Arthur O’Neil also tells us separately, when discussing the three meetings at Granard in 1784, 1785 and 1786, that Charles Fanning got the first prize at all three balls. O’Neil tells us that the tune he played at the first two was The Coolin. I am very interested in O’Neil’s information that “He never taught any but merely was an amateur and principally supported himself by the private emoluments arising from his profession”. Perhaps Arthur O’Neil seems to be thinking that it was teaching that made the difference between an amateur and a professional.

1792

Arthur O’Neil tells us:

I next heard of his being in Belfast in 1792 at the time of the Celebration of the French Revolution where I met him, where he got the Highest prize for his performce on that occasion.

Arthur O’Neil, Memoirs (revised version), Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections MS4.14 page 77-79

The thing that leaps out at me here is how Arthur O’Neil describes the famous gathering of the harpers in the Exchange Rooms in July 1792. Nowadays this event is generally known as the “Belfast Harp Festival” so I am amazed to see O’Neil calling it “the Celebration of the French Revolution”. I think that shows how modern day preconceptions are very different to late 18th century ones, as if the gathering of the harpers was secondary to the commemoration of the fall of the Bastille, even to one of the harpers themselves.

The Bastille celebrations are mentioned in this preview advert:

The Meeting of the IRISH HARPERS

Belfast Newsletter, Tue 3 Jul 1792 p3

AT BELFAST,

IS to be held in the EXCHANGE-ROOMS, on Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and Saturday (the 11th, 12th, 13th and 14th July instant). — The Entertainment to commence at One o’Clock each Forenoon, excepting Saturday, when, on account of the Review, it will be held at Seven in the Evening. — It is requested that the Subscribers will immediately pay their Subscriptions.

Admittance for the four Nights to Non-Subscribers, Half a Guinea; the Tickets transferable.

Tickets for Non-Subscribers to be had at Mr. Joy’s, Mr. Magee’s, Mr Bradshaw’s, and the Coffee-Room.

Belfast, July 4th, 1792.

*⁎* On Account of the Coterie, the Meeting is unavoidably postponed from Tuesday to Wednesday.

Half a Guinea is a lot of money, the equivalent of perhaps a hundred pounds or more today.

On Friday 13th, the third day of the meeting (so presumably reporting on the first two days’ performances), the newspaper printed an article which included a list of the harpers and the tunes that each played. I think the names are given in the order that they performed; Charles Fanning is listed third, after Dennis Hampson and Arthur O’Neil:

…

Belfast News Letter, Fri 13 Jul 1792 p3

CHARLES FANNING, from the co. of Cavan, aged 56.

Played – Condou Dee Lish } Author and Date un-

or Black Headed Deary } -known

Rose Dillon and Jig – Carolan

Colonel O’Hara – Same.

…

When it says “from the county of Cavan” I assume that this means that Fanning was living or based somewhere in County Cavan in the spring and early summer of 1792.

We are give three tune titles here that Fanning is said to have played in Belfast in July 1792. The first, Ceann dubh dílis (which translates as something like dear dark head), used to be well known in both Irish and Scottish traditions but seems to have fallen by the wayside. You can read a lot of commentary and see some source notations at tunearch. The traditional song lyrics are now usually sung to a newly composed tune. Rose Dillon is a very interesting Carolan tune, for which we apparently have a live transcription from a harper; I wrote it up as part of my Transcriptions Project a few years ago. Colonel O’Hara (DOSC 129) only seems to be attested in Edward Bunting’s piano arrangements, in QUB SC MS4.33.3 p44-5 and in the 1809 printed book p54.

A couple of days after the events had finished, Charles Fanning placed an advertisement or notice in the newspapers:

CHARLES FANNING requests the Ladies and Gentlemen of Belfast and its Neighbourhood, Lovers of Harmony and friends of the native Music of their Country, to accept his grateful thanks for the kind countenance he received during the late Assembly of Irish Harpers in the Metropolis of the North.

Belfast Newsletter Tue 17 Jul 1792 p3, reference via John Scully, Ah how d’you do sir, (Carrickmacross 2024), p8

And a couple of days later, the Northern Star published a review of the events that previous weekend:

… The Harpers were assembled in the Exchange-Rooms, and commenced their probationary rehersals on Wednesday last, and continued to play about two hours each succeeding day till Saturday; – after which the fund, arising from subscriptions and the sale of tickets, to a considerable amount, was distributed in premiums (or donations) from ten to two guineas each, according to their different degrees of merit. The highest premium was adjudged to CHARLES FANNING, (from the County of Cavan,) who, from having the advantages of sight, and opportunities of acquiring a knowledge of the taste and fashion of modern music, has arrived at a degree of perfection not easily attained, and which must have given the hearers a very high idea of this kind of Music, in producing, alternately, the most lively, plaintive and pathetic sensations.

The Northern Star Wed 18 Jul 1792

… [list of tune titles]…

Professional gentlemen are now employed in taking down some of the above airs, and, it is said, they have a pleasing effect when applied to the harpsichord, violin, &c.

Many decades later, in his reprint of the newspaper reports, Edward Bunting commented:

Fanning was not the best performer, but he succeeded in getting the first prize, by playing “The Coolin,” with modern variations; a piece of music at that time much in request by young practitioners on the piano forte.

Edward Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland (1840) intro p.64

We have a couple of comments here that seem potentially related. The Northern Star describes how Fanning, “acquiring a knowledge of the taste and fashion of modern music, has arrived at a degree of perfection not easily attained”. We know that Charles Fanning played the traditional wire-strung Irish harp in the inherited tradition; and he is choosing to play tunes that had been composed by Carolan a couple of generations previously. Would Fanning’s repertory have been considered “modern”, or was it his style and presentation that fitted into this pre-conceived category? The concepts of “ancient” and “modern” in music were starting to be argued about in the 1790s; for a good discussion of this late 18th and early 19th century argument see Howard Irving, Ancients and Moderns (Ashgate 1999). I need to do more work on this to understand how Fanning’s modern “taste and fashion” contrasts with the Belfast Gentlemen’s obsession with the “ancient music of Ireland”.

I am not entirely sure how to take Bunting’s comments from almost 50 years later. He could have been paraphrasing and exaggerating the Northern Star report, or he could have been genuinely remembering details of Fanning’s repertory and style. I have written up the different versions of The Coolin where I discuss some of these issues.

We have another fascinating reference to Fanning at Belfast in 1792, this time from an “insider”, the traditional Irish harper William Carr, whose remarks were written down by the English traveller John Lee in Drogheda on Wed 18 Feb 1807:

Charles Fanning Co Cavan (got 1st Prize, 10Gs. Was best player by much)

ed. Angela Byrne, A Scientific, Antiquarian and Picturesque Tour (Routlege 2018) p303

Meeting with Edward Bunting

Edward Bunting was employed as a literate classical musician to attend the meeting in Belfast in July 1792, and was commissioned by the organising Gentlemen to “transcribe and arrange” the music of the harpers, so as to take the repertory out of its traditional context, and re-imagine it as mainstream European classical piano music.

I have written before about Edward Bunting’s collecting process; I do not know how much Edward Bunting actually wrote down in the Assembly Rooms; he only had a couple of hours each day for four days, and as a classical organist and pianist he would have been totally unfamiliar with the sound and playing style and idiom of the traditional harpers playing wire-strung Irish harps. I suspect he may have spent the time at the meeting collecting names, tune titles, and networking with the Gentlemen and trying to get his hands on books of already done classical arrangements of Irish tunes. And he certainly started planning almost at once to go out to visit harpers and other traditional musicians to collect more tunes.

Bunting did not leave records of his activities so it is all a bit vague and unsatisfactory. We can check my Transcriptions Project Tune List Spreadsheet to see that Charles Fanning was tagged by Bunting as the source for a number of tunes he collected. Titles tagged with Fanning’s name include Molly Bheag Ó, Lady Blayney, Rose Dillon, Madam Maxwell, Betty O’Brein or Kitty O Brian, Bob Jordan, Loftus Jones, Carolan’s Concerto, Planxty Thomas Judge, Colonel O’Hara, Madam Bermingham and Jig, Mrs Crofton, and Sir Festus Burke. However it would be the height of naivety to think that these piano arrangements are representations of Fanning’s traditional performances. Some of these attributions may be fabricated, or transferred to a piano arrangement from the newspaper articles; others may be genuinely telling us that Bunting had worked up a piano arrangement which ultimately derived from his rough field notation, when he had transcribed a tune live from Fanning’s playing. I have written up some of the live transcription notations and I discuss there the issues with attribution and provenance. I think it is quite possible that Bunting never actually met Fanning again after July 1792, and never actually transcribed anything live from his playing. It is possible that all of these attributions are spurious, added on to piano arrangements of tunes that Bunting had originally sourced from other harpers or earlier printed books.

One thing I note is that many of these tune titles are of Carolan tunes, and that most of them have not been passed down to us in the living tradition of Irish music, but have been re-introduced into the tradition much more recently from printed books.

Bunting also mentioned Charles Fanning as one of the harpers who he had noted down information about the fingering techniques from. We don’t have any paper trail for this aspect of the collecting, only the finished chapter of the 1840 book (intro p.18-28). Bunting says on page 20 “The harpers whose authority was chiefly relied on were Hempson, O’Neill, Higgins, Fanning, and Black”. but it is not clear how this process worked; I have the impression that Dr. James McDonnell may have been largely responsible for this collecting work.

Fanning’s harp

We have a very brief description of Charles Fanning’s harp. This is part of a letter that Dr James McDonnell wrote to Edward Bunting, I think in later 1839 or early 1840 when Bunting was finishing his 1840 book ready for publication. James McDonnell is discussion various things, and includes brief notes on some of the harps that the traditional harpers who had played in Belfast almost 50 years previously had used:

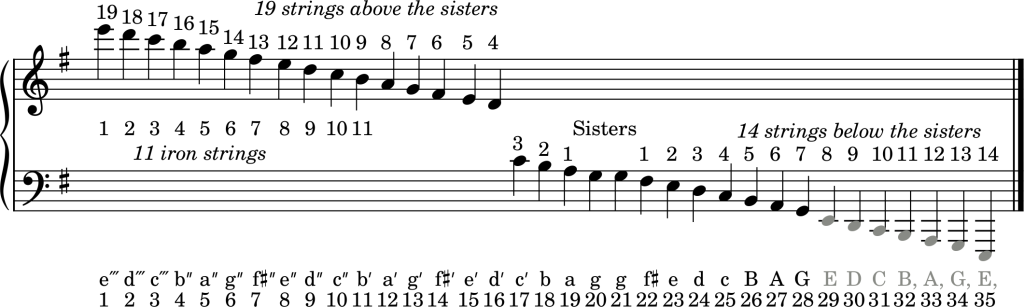

Fanning’s harp had 35 strings, 14 below, & 19 above the Sisters – <the 11 upper strings of iron wire -> Mr Shannon, an organist, I believe, at Randlestown (when there was no organ at Belfast) constructed a Gamut for Fanning’s harp.

Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.35.16

…

With a view to discover the theory of the curve of the Pinboard I had all the Harps measured carefully& prepared forpreparatory to engraving them upon a scale, but th[e]se notes are lost by Mr John Mulholand, who took them to London [&] I had no duplicate.

I think John Mulholland is the collector who published a collection of ancient Irish airs in 1810. The first organ in Belfast was I think the Snetzler organ in St Anne’s Cathedral, installed in 1781 (David Byers). I am not finding references to Mr Shannon at Randalstown before 1781. I am also not entirely sure what “constructing a gamut” for a harp might involve. Perhaps it just means writing down the list of all the notes, like Edward Bunting did for Dennis Hampson’s harp.

In the absence of Dr. McDonnell’s measurements, or Mr Shannon’s “gamut”, all we have are the count of strings. However, James McDonnell’s string count is very useful. He tells us that Fanning’s harp had 35 strings, 14 below the sisters and 19 above. The two “sister” strings are clearly in addition to the strings above and below, so we can draw a chart showing this, and also showing the 11 highest strings of iron wire:

I have shown the lowest 7 strings greyed out because I don’t actually know how Fanning might have tuned these strings. No.28 is “Cronan” G, and then it seems normal and necessary to have a gap below that, so that the string 29 can be retuned to be either E or F depending on the harp tuning. My copy of the NMI Carolan has this same bass string count (it has one extra treble string) and I have experimented with different ways of organising these lowest positions. I think the lowest 4 or even 5 strings are never played, but only contribute sympathetic resonance to the harp. Bunting calls these lowest strings the “organ” strings in his field notebook, QUB SC MS4.29 pages 81, 150 and 156. See my post about the live transcription of the harp tuning sequence for more on this.

This description does not seem to exactly match any of the extant harps so I suppose we have to presume his harp has been destroyed.

After 1792

I am not finding any references to Charles Fanning after July 1792.

I don’t know when he may have died. William Carr lists some of the harpers in 1807 as “dead” but he does not say that for Fanning. But I think we can’t use that as evidence that Charles Fanning was still alive in 1807. Gráinne Yeats says that he “died c.1800” but I don’t know her source for this statement and she sometimes gets dates wrong (Féile na gCruitirí Béal Feirste 1792, Gael-Linn 1980, p58-9, also The Harp of Ireland Belfast Harpers’ Bicentenary Ltd, 1992, p.62). Ann Heymann says he died c.1809 but again I don’t know the source for this date. (Legacy of the 1792 Belfast harp Festival, 1992, p21)

I suppose we need to wait and hope to stumble on a death notice or some other mention of him.

My map shows the places mentioned above.

Interesting!

As you mention his father, a farmer, it also makes me wonder how many people would have a harp in the house.

Thank you so much for all this info, Simon! It was a joy to read and learn all this.

Its very hard to say because we know so little about the traditional harpers through the 18th century. Our information only really picks up into the 19th century, which is why my “study period” begins in 1792.

Re Harriot’s query: An elderly welsh harpist, many years ago told me that in his youth he worked for an electricity supply company, and used to visit a great many houses to read their electricity meters. He said he was surprised to find so few Welsh houses had harps!