Dennis Hampson (also known as Denis, Hempson, O’Hampsey, and other variants) was a traditional Irish harper in the 18th century. He lived through into the early 19th century and so he has a place in my “Long 19th Century” project.

Most of the accounts of Dennis Hampson’s life concentrate on the earlier part, up to him going to Belfast in 1792, or on the tunes that Edward Bunting collected from him in the 1790s. However, in other posts as part of my Long 19th Century project I have been tracking down the life-stories of traditional harpers from 1792 onwards. So in this post, I am going to try and talk about what Dennis Hampson was doing where and when, starting in 1792. I am not going to deal with any part of his life before 1792 because people have done that elsewhere.

As we found with Thomas Shea, the evidence and information for the 18th century harpers who were still alive in 1792 is very different from the evidence for later generations of traditional harpers through the long 19th century. For these earlier individuals, we have a lot more secondary descriptive accounts and a lot fewer primary sources. This makes it harder to get close to the person, and harder to pick apart what they were doing when. Everything is filtered through outside observers, who have their own agenda to cast the tradition in a certain light. It is a different problem from how the 19th century evidence is filtered through the commercial notices in newspapers.

I think we should start by discussing where he was at in his life in 1792. Then after discussing his patron, his house and his family, we can try to build a life-story year by year from 1792 through to his death. And then after that we will consider his harp and his legacy.

But we should start with the most basic stumbling block – his name.

His name and age

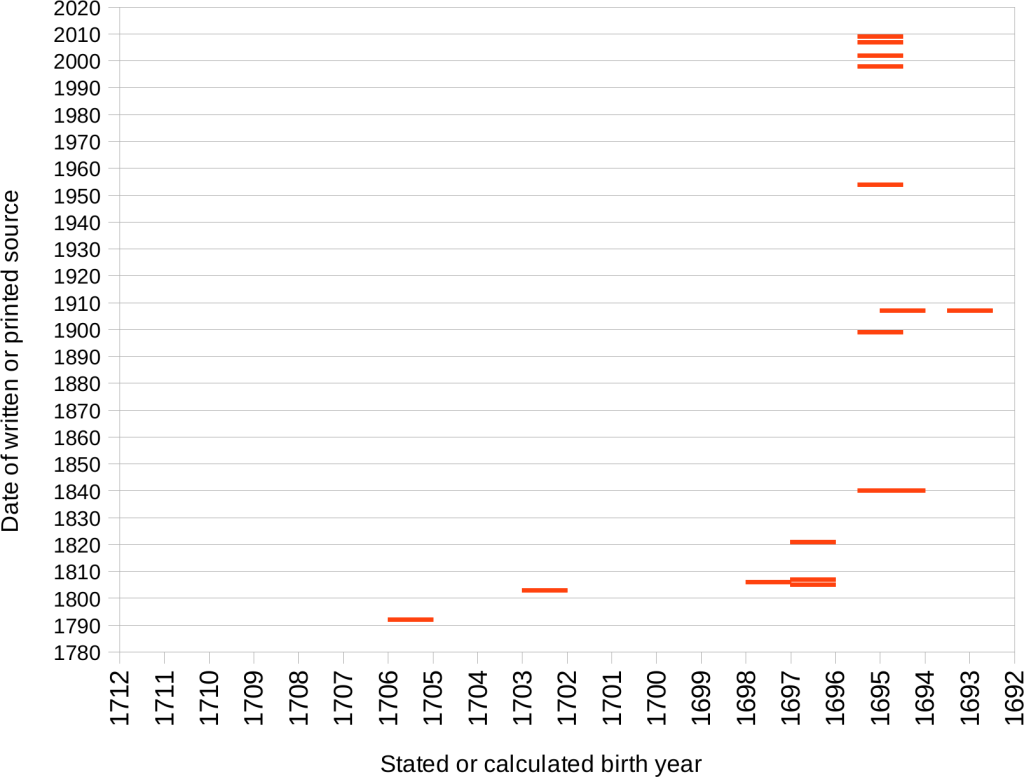

Since his first appearance in the records in 1792, Dennis Hampson’s name and age have been given differently by almost every person who has written about him. I made a chart to try and line up all the different evidence. I am sure I have missed a number of later 19th century and 20th century references but this will do for now to show the overall pattern.

| Date | Person | Source | Forename | Surname | Age / year of birth (calculated) |

| 10 July 1792 | | The Belfast News-Letter p3 | Dennis | Dempsey | 86 (=1705-6) |

| 1790s | Edward Bunting | QUB SC MS4.29 p44 | Dennis | a Hempson | |

| 1790s | Edward Bunting | QUB SC MS4.29 p87, 153, 160, 190 | | Hempson | |

| 17 March 1803 | Patrick Lynch | QUB SC MS4.26.46x | Dinnis | a hamp[s]y | 100 (=1702-3) |

| [1803] | Patrick Lynch | QUB SC MS4.26.2.a | Dinnis | hampsy | |

| [1803] | Patrick Lynch | QUB SC MS4.26.2b | Dennis | Hempson | 100 (=1702-3) |

| [1803] | Patrick Lynch | QUB SC MS4.26.2c | Dennis | Hampson | |

| 3 Jul 1805 | Rev Sampson | The Wild Irish Girl | Dennis | Hampson | 108 (=1696-7) |

| 1806 | Sydney Owenson | The Wild Irish Girl | | | “in his hundred and ninth year” (=1697-8) |

| 18th February, 1807 | William Carr | Lee | Dennis | Hampton | |

| 21 Nov 1807 | | Obituary (Belfast Commercial Chronicle Plus other newspapers) | Denis | Hampson | 110 (=1696-7) |

| c.1808 | Arthur O’Neill | Belfast central library, F.J. Bigger archive V6 | | Hempson | |

| 7 Mar 1809 | Irish Harp Society minutes | Hampson | |||

| 1809 | Edward Bunting | General Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland intro p.ii | Dennis | Hempson | |

| 1821 | Richard Ryan | Biographia Hibernica vol 2 p.304 | Dennis | Hampson | 111th year of his age in Nov 1807 (1696-7) |

| 1829 | | The Irish Shield and Monthly Milesian, 1 ix 1829 p351 | Denis | Hampson | |

| 25 May 1835 | his daughter Catherine McKeever, and others | Ordnance Survey Memoirs | Dennis | Hamson | |

| 1837 | Samuel Lewis | v2 p592 | Dennis | Hampson | |

| 1840 | Edward Bunting | Ancient Music of Ireland p73 | Denis | a Hampsy or Hempson | 1695 |

| 1840 | Edward Bunting | … p76 | | | Died 1807 aged 112 (=1694-5) |

| 1846 | William J O’Neill Daunt | Hugh Talbot: a tale p436 | Denis | Hampson | |

| 1849 | John Bell | Glasgow University Library, MS Farmer 332 f1v | | Hemsten | |

| 1849 | John Bell | Glasgow University Library, MS Farmer 332 f2r | Dennis | Hempson | |

| 1899 | Feis Ceoil Loan Exhibition | Irish Independent, 17 May 1899 p4 | Denis | A. Hempson | 1695 |

| 1905 | W. H. Grattan Flood | The Story of the Harp p132 | Denis | O’Hampsey | 1697 |

| 1905 | W. H. Grattan Flood | … p109-110 | Hempson | ||

| July 1906 | F.J. Bigger | UJA xii 3 p110 | donnchadh | o’hámsaigh | |

| July 1906 | F.J. Bigger | UJA xii 3 p110 | Denis | O’Hampsay | |

| 1907 | Irish International Exhibition, Dublin | Hempson | 1693 | ||

| 1907 | Irish International Exhibition, Dublin | Denis | Hampsey | 112 in 1807 (1694-5) | |

| 1954 | Richard Hayward | The Story of the Irish Harp | Denis | Hempson or O Hampsey | 1695 |

| 1959 | Colm Ó Lochlainn | book review, Studies 48/190 | Denis | Hampson | |

| May 1 1964 | Cathal O’Shannon | Evening Press | Donnchadh | O hAmhsaigh | |

| May 1 1964 | Cathal O’Shannon | Evening Press | Denis | Hempson | |

| 1992 | Brian Audley | Denis O’Hampsey, the harper | Denis | O’Hampsey | c.1695 |

| 1994 | Ann Heymann | Queen of Harps CD | Dennis | Hempson | |

| 1998 | Limavady Borough Council | Memorial stone, St. Aidan’s Church | Denis | O’Hampsey | 1695 |

| 1998 | Jim Hunter | O’Hampsey: The last of the Bards | Denis | O’Hampsey | 1695 |

| 2002 | Ann Heymann | article on harpspectrum.org | Denis | O’Hampsey | 1695 |

| 2002 | Ann Heymann | article on harpspectrum.org | Donnchadh | Ó Hámsaigh | 1695 |

| Sat 10 Nov 2007 | Limavady Borough Council / HHSI | Concert programme booklet | Denis | O’Hampsey, Hampson | 1695 |

| Sat 10 Nov 2007 | Limavady Borough Council / HHSI | Concert programme booklet (Irish language section) | Donnchadh | Ó hÁmsaigh | |

| 2009 | Dictionary of Irish Biography | | Hempson | | |

| 2009 | Dictionary of Irish Biography | Denis | O’Hempsy | “1695?” |

There are different things we can take from this chart. First of all, the age. There is no consensus as to when Dennis Hampson was born; the usual date of 1695 seems to derive from Edward Bunting’s 1840 book. All earlier sources make him younger than that.

Perhaps more interestingly, we can see that the estimated or stated birth year is gradually pushed earlier over time. I made a visualisation of the different stated or calculated birth years:

The trend is obvious; from 1792 onwards he is gradually claimed to be ever older, until 1840 when Bunting’s hugely influential book sets the accepted norm. I would be tempted to believe the earliest testimony, that he was born perhaps 1705-6, if not even later, making him aged 100 or less when he died.

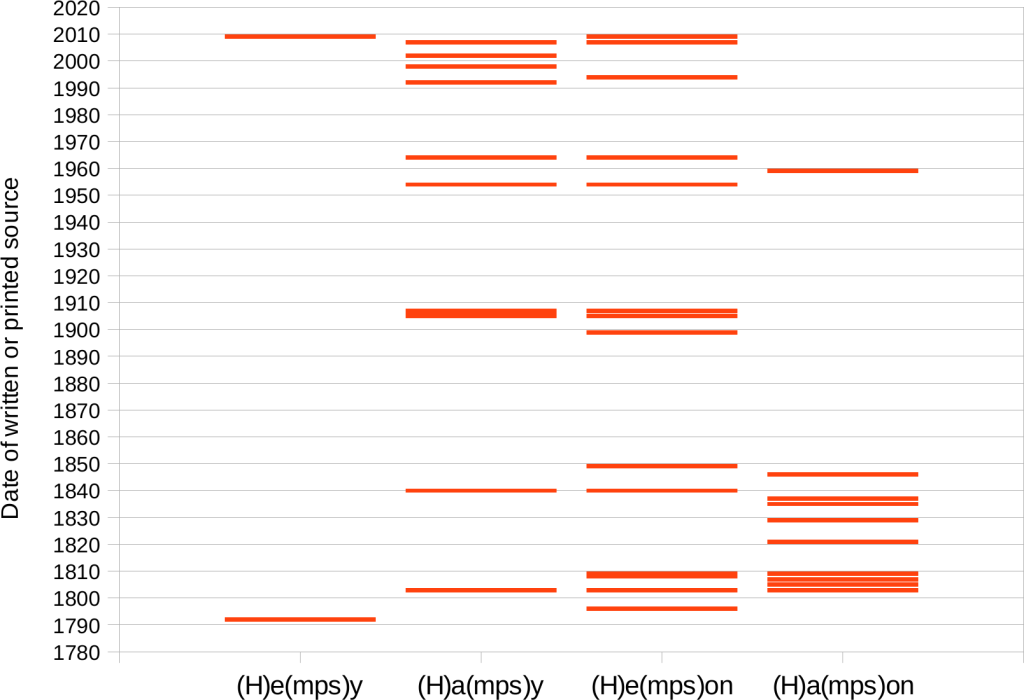

The names are also interesting to see. I think we can understand all these different variant names as basically falling into four main groups, depending on the vowel (-a- or -e-) and the ending (-on or -y). I am ignoring whether or not the name is given starting with O’- and whether the ending is written in English or Irish orthography (-y or -aigh)

Again we can make a chart to visualise these four groupings:

The main thing that I notice is that all four variants are attested back in Hampson’s lifetime.

Sylvia Crawford points out to me that in the accents spoken in County Derry (at least inland) the sound of -a- and -e- can be very similar, being pronounced more like “-a”. Of course Hampson was blind and would not write his name; and spellings of names were less standardised in the 1790s and early 1800s than nowadays

The genealogist Fiona Pegrum has pointed out that Hempson / Hampson has different roots from O’Hempsy / O’Hampsy, and should really be considered different names. I have not followed this up properly, but I think the implication is that Hempson or Hampson is originally an English name. More genealogical research can hopefully tell us whether Dennis Hampson was descended on his father’s side from planters who came from England in the early 17th century to settle in County Derry.

We could also look at who is using which name. Bunting consistently uses Hempson, but he is very Anglo I think. Anyone after 1840 is going to be heavily influenced by Bunting’s use of “a Hampsy or Hempson”. Rev Sampson was an old family friend and I understand he was an Irish speaker; he consistently uses Hampson, but we don’t have his original report, only the printed footnote in Sydney Owenson’s novel. Dennis’s own daughter Catherine McKeever seems to be using Hamson, yet this is secondhand oral testimony from her so we cannot fully trust this spelling (and the 1991 published edition of her information “normalises” the spelling, to muddy the water a bit more). Patrick Lynch was an Irish language scholar, so we could perhaps trust him to know best, but he uses three different spellings, which is not very helpful. I also don’t know what the significance is of Lynch spelling the first name “Dinnis”.

F.J. Bigger in 1906 seems to be the first to use Irish orthography for Hampson’s name, though in an English-language context. He announces “the proper Gaelic spelling of O’hámsaiġ”, i.e. O’hámsaigh, with the name printed in Gaelic type (UJA xii 3 p110). He then muddies the water by inventing a phonetical back-Anglicisation spelling “O’Hampsay” (with the “-ay” ending); and then when he quotes some of the primary sources, he silently edits them all to use his new invented “O’Hampsay” spelling, including (unfortunately) the account of local traditions written for Bigger by L. A. Walkington in 1905 (p102). Bigger’s Irish orthogaphy is not really very correct; the form O’- is an Anglicised version of the Irish Ó -. His version of the Irish spelling of the name can be normalised to Ó hÁmsaigh, which has become the usual form used nowadays in Irish-language contexts. I do not know if Cathal O’Shannon’s suggestion of “O hAmhsaigh” has any merit. In any case, Ó hÁmsaigh seems to be an incredibly rare surname and I am finding hardly anyone called Ó hÁmsaigh or Ó hÁmhsaigh except for our man Dennis Hampson.

Bigger also seems to be the first to Gaelicise the first name as Donnċaḋ, i.e. Donnchadh, with the name printed in Gaelic type (p102). This may be totally spurious. The earliest sources all use Dennis with two “n”s; the spelling Denis with one n appears slightly later and is less common in the early sources though it seems to have taken over more recently.

So what should we call him now? Hempson, Hampson, Hamson, O’Hamsy, O’Hampsy, O’Hampsey, O’Hampsay, O’Hempsy…? I note that the great majority of the early sources use the “-son” form of the name rather than the “-y” form, which only really gains much traction in the 20th century. Presumably this is connected to the Gaelic revival, and a desire to present the harper as more Irish; the use of the Irish spelling “Ó hÁmsaigh” in English-language contexts is the logical end-point of this trend.

I think I would prefer to follow the early sources including his own daughter, his friend Rev. Sampson, and his obituary, in using the “-son” form of the name. And though “Hempson” seems to have become the default since Bunting’s book in 1840, I think I actually prefer “Hampson” not only because of the pronunciation issues mentioned above, but also because this “-a- -son” form is again what we see his daughter, his friend and his obituary using.

Tá sé seo ar fad i mBéarla. Ach nuair a labhraímid nó nuair a scríobhaimid i nGaeilge faoi (ar ainm.ie mar shampla) tá ceist eile againn. Níl a fhios agam cad é is fearr. An bhfuil Donncha Ó hÁmsaigh ceart nó an bhfuil Dennis Hampson níos ceart? An bhfuil sé ceart go leor ainm a aistriú ó Bhéarla go Gaeilge?

Language

Dennis Hampson certainly had Irish. Patrick Lynch collected the lyrics of Irish songs and fragments from him in 1803 (see below), and also Edward Bunting wrote down English words that are associated with the tune Burns’s March, which were “translated by him” (QUB SC MS4.33.3 p.19). But Hampson was certainly also a fluent English speaker; he worked in the upper-class Anglo-Irish Ascendency millieu, and he lived in what I think was a majority English-speaking area. Magilligan, and in fact the whole area between Binevenagh and Lough Foyle, were majority English- (or perhaps Scots-) speaking areas back as far as 1800 if not earlier, presumably because of the 17th century plantations. I am having trouble finding solid info on language distribution in this area during the 18th century. In 1834, O’Donovan travelled through Magilligan looking for Irish language place names and traditions associated with them. In his manuscript letters he wrote:

Newtown Limavady, Aug 16th 1834

OS letters, page 56 (227) (PDF p150)

on Monday I intend to travel thro’ Magilligan: few of the “aborigines” or Irish speaking people are to be found in it, but I am told that a few have retained the language in consequence of their communication with the opposite side – Inishowen. Of this I am doubtful but I must try –

Two days later O’Donovan was past Magilligan and in Coleraine, and had nothing at all to say about Irish language place names or traditions except for discussion of one word he got from Revd Butler. He was not finding Irish place-names or information about them from the Magilligan locals. It looks like he may not have found any Irish speakers there at all.

We will discuss Dennis Hampson’s harp more below, but this is a good place to think about its language issues. I remember standing with Diarmaid Ó Catháin in front of the Downhill harp in the Guinness Storehouse Museum a few years ago, and he remarked that the inscriptions were in English, not Irish. Both the name down the forepillar, and the poem on the soundbox, are in English, including the maker’s name. I think there are huge issues of language politics at play here that we need to think about, from the primacy of English as the language of the colonial oppressor in the 17th and 18th century, to the cultural significance of Irish since the Gaelic revival of the 1890s. None of these historical language matters that we have been discussing can be considered without placing them in this difficult and complex context. As always I recommend Aidan Doyle, A History of the Irish Language (OUP 2015) for a quick overview to put these things in perspective.

His patrons

Dennis Hampson had a number of patrons through the 18th century, from as soon as he finished his studies and started to make a living working as a traditional harper. However for this post we are only concerned with his patrons from 1792 onwards.

Hampson’s landlord and patron in the 1770s and 1780s had been Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry (1730-1803). He was fabulously wealthy; he was made Bishop of Derry in 1768, and started constructing Downhill House to be his Bishop’s Palace in the early 1770s, finally moving in in 1779. He seperated from his wife in 1782 and was estranged from his son, but he was very close to his cousins, especially Frideswide Mussenden (there are rumours it was more than a friendship); he built the famous Mussenden Temple at Downhill as a gift to her in 1785, the same year that she died.

Frederick Hervey the Earl-Bishop seems to have been a good patron to Hampson and his family, giving land rent-free for them to build a house, and giving cash to pay for the building, and also calling by to give the family money during the “dear year” (though I don’t know what year this was).

However, Frederick Hervey’s patronage of Dennis Hampson dates to the time before our study period; Hervey was often away travelling and made six Grand Tours of Europe, where he bought many of the paintings that were in his stupendous art collection at Downhill. He was away in Italy from about 1791-2 right through until his death on 8 July 1803, and so was not in Ireland for any of our study period (1792 onwards)

Frederick Hervey had appointed his cousin, Rev. Sir Henry Hervey Aston Bruce (d. 1822), (who was also Frideswide’s brother), to be a kind of steward of Downhill House when he was away; I understand that Henry lived at Downhill House from about 1791 onwards, and then inherited full ownership of the house in 1803.

We know that Frederick Hervey had been a good patron to Hampson, but it is not clear what kind of relationship Hampson had with the cousin Henry Bruce. Sampson’s letter of 1805 only talks about Frederick Hervey the Earl-Bishop, even though he had not been seen in Ireland for 13 years at that point. So it is interesting that Sampson’s letter of 1805 does not lavish the same praise on Henry Bruce, who had been the resident caretaker of the Downhill estates from c.1792 through to 1803, and was the actual landlord and owner of the estates from 1803 onwards.

In Hampson’s obituary we are told that Henry Bruce and his family “were in the habit of stopping to hear his music”, though this may be just the newspaper obituary writer being deferential to the aristocratic landlord. We also have Walkington’s reporting of local traditions in 1905, that Hampson “was often at Downhill Castle playing for Sir Henry Bruce” (UJA xii 3 p103), but this may be a conflation between Frederick Hervey the late Earl-Bishop, and Henry Hervey Bruce his cousin and successor, and Henry Hervey Bruce the grandson who was the owner of Downhill in 1905.

We have other information which tells us what Henry Bruce the cousin was like. This is contained in a lengthy footnote to a poem in praise of Hampson’s harp, which the poet had seen in Downhill House. The footnote describes Magilligan, and Downhill, and praises Hampson’s old patron Frederick Hervey Earl of Bristol, and mercilessly slams Frederick’s cousin Henry Hervey Bruce who inherited Downhill House in 1803:

He [i.e. Frederick] was succeeded in his property and Irish estates by his cousin, SIR HERVEY BRUCE, a man of little mind and vitiated taste. This unworthy successor of the learned and munificent Earl of Bristol, despoiled the mansion of Down Hill of all its pictures, sculptures, medals and antiques, which he sold; and before his death, an event which happened only three or four years ago, he not only deprived the old widow of Denis Hampson of the cottage, which the Earl had bestowed on the minstrel, but actually carried off the harp for arrears of rent.

The Irish Shield and Monthly Milesian, Vol 1 no ix, September 1829 p351

Rev Sir Henry Hervey Bruce died in 1822; but we are not told how long before then the eviction and the seizure of the harp may have happened. We can wonder how this story would fit into a timeline. We know that Frederick Hervey was extremely wealthy and had built up a stunning art collection and library at Downhill house. Henry Bruce inherited Downhill House and the estates when Frederick died in 1803; Hampson died in November 1807. Rebecca Campion notes in her PhD thesis (Maynooth 2012) on Frederick Hervey’s art collecting, that “his heirs were impoverished by his excessive spending and forced to sell a great number of artworks after Hervey’s death… Sir Henry Hervey Bruce sold the collection in Rome in 1804 … and 88 pictures in December 1813 at auction in Dublin … He tried to sell two landscapes by Claude Lorrain in London in 1818” (PDF p.208, fn116).

I wonder if Frederick’s rent-free grant of land for Hampson’s house was a specific legal grant to Dennis Hampson, which Hampson could exercise for his whole life, even after a change of landlord, but after Dennis Hampson’s death I wonder if his widow would become liable for the usual annual rent? The old people interviewed by Walkington in 1905 (UJA xii 3 p103) said that Frederick had granted the land to Hampson “himself and his descendents for ever” but this is not entirely clear.

We have another record of a potential interaction between Rev Sir Henry Hervey Bruce and the family of Dennis Hampson. In the minute book of the Irish Harp Society for Tue 7 Mar 1809, the Gentlemen of the Committee discuss a letter:

Resolved that a letter be written to Sir Hervey Bruce on the subject of old Hampsons Grandson who has applied to be admitted as a scholar requesting his aid to the Institution in consequence of his having patronised that family

Minutes of Irish Harp Society committee meeting, Tue 7 Mar 1809. Belfast, Linen Hall Library, Beath Collection 5.1 p19

So, just a year and a half after Dennis Hampson died, his daughter’s son, who would apparently have been called McKeevor, must have applied to be a scholar at the harp school in Belfast under Arthur O’Neil (this was a month or so before the harp school moved to Pottinger’s Entry I think). The Society seems to have not had enough money; and so they wanted Sir Henry Hervey Bruce to contribute to the costs. Usually, an applicant had to have a Gentleman reference to apply to the school. Perhaps young McKeever did not have a reference but approached the Gentlemen directly asking to be admitted. We don’t have any more correspondence; we don’t have the application and we don’t have the letter that the Harp Society sent to Rev. Sir Henry. And we don’t have any reply from him, and we don’t have any records of a harp student called McKeevor or McIvor or similar.

My speculation might be that by 1809, Dennis Hampson’s widow and daughter and family may have already been estranged from their landlord Sir Henry Bruce. But that may be way off beam. I don’t know.

His family

Dennis Hampson married old, most likely after he had retired from his touring career and wanted to settle down. Patrick Lynch the song collector tells us the wife’s name, and their ages, though as mentioned above, we can’t take any of these quoted ages at face value.

…

Patrick Lynch, list of elderly people in Magilligan, 17 March 1803. Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.26.46x

Dinnis a Hampsy of Ballymaclary – 100

his wife Nanny Dougherty – 66

…

Rev. George Sampson visited the house on Tue 2nd July 1805, and he tells us more about the family:

He came to Magilligan many years ago, and at the age of eighty-six, married a woman of Innisowen, whom he found living in the house of a friend. “I can’t tell,” quoth Hampson, “if it was not the devil buckled us together; she being lame and I blind.” By this wife he has one daughter, married to a cooper who has several children, and maintains them all…

… his daughter now attending him is only thirty-three years old…

Rev. G. Sampson, Wed 3rd July 1805, letter to Sydney Owenson, published by her in The Wild Irish Girl 1806 [3rd edition 1807 vol 3 p104]

So if the daughter was 33 in 1805, then she must have been born in 1771-2; but the age given for Hampson when he married (86) is obviously spurious so I don’t know if we can trust any of these ages. But if we believe the daughter’s age, she would be about 20 years old in 1792. I don’t know when the daughter married. In the Ordnance Survey memoirs there is information about Dennis Hampson which was obtained from “Dennis Hamson’s daughter Catherine McKeever” on 25th May 1835; she would presumably have been aged about 63 then. (unpublished typescript via Ann and Charlie Heymann, published in Ordanance Survey Memoirs… vol 11, Institute for Irish Studies, 1991 p115 and 129)

The reference about Nanny Dogherty being from Inishowen is very interesting since it fits with O’Donovan’s later information about connections between Magilligan people and Inishowen people on the other side of the water.

Walkington in 1905 (UJA xii 3 p103) gives traditionary information about Dennis Hampson’s family, but it seems garbled and doesn’t seem to match the earlier information we have. Walkington got this information from old people living in Magilligan. They said that “the family has quite died out”. They said that Hampson’s daughter “never married” and acted as a guide to him; they thought that he had “two sons and another daughter”. This might be a garbled memory of Hampson’s McKeever grandchildren I suppose. I’m not sure this information is very useful.

Anyway we can summarise Hampson’s family in the 1790s and early 1800s: he is living with his much younger wife, Nanny Dogherty, who was perhaps 30 or 40 years his junior. He is also living with their daughter, Catherine McKeever, and her husband, Mr. McKeevor (Dennis Hampson’s son-in-law), and their children, who were Dennis Hampson’s McKeevor grandchildren. It must have been a busy wee household!

His house

We have information about the house:

Lord Bristol … gave three guineas, and ground rent free, to build the house where Hampson now lives. At the housewarming, his lordship with his lady and family came, and the children danced to his harp…

Rev. G. Sampson, Wed 3rd July 1805, letter to Sydney Owenson, published by her in The Wild Irish Girl 1806 [3rd edition 1807 vol 3 p105]

Frederick Hervey’s children were born between 1753 and 1769; Hervey separated from his wife in 1782. So the house must have been built before then. My guess is that the house may have been built in the early 1770s, since that is my guess for when Hampson may have got married. But this is just pure guesswork. We should also collate this possible timeline against Hervey’s own career; Fiona Pegrum said in a talk in July 2022 that Hervey was in Ireland from 1772 to 1776, and suggests that Hampson’s house may have been built during that time.

Walkington in 1905 (UJA xii 3 p103) reports local traditions that Denis Hampson’s house stood opposite Lafferty’s pub, now the Anglers Rest. I think the house must have stood diagonally opposite the pub, because we are told by Lynch (see above) that Dennis and his wife Nanny lived in Ballymaclary townland. The townland boundary runs along the track across the main road, and the big willow tree and the pub are across the boundary in the next townland (Benone). There is a house on that south-east corner visible on the first edition Ordnance Survey map (Surveyed: 1831, Engraved: 1832, Printed: 1837).

In the Griffiths Valuation of 1858, this house (3c) does not have any land with it, and had a rateable value of 15 shillings. It was occupied by Benjamin McVetridge, who held it from William Cathers, who held Ballymaclary House and 45 acres of land in Ballymaclary townland from Sir Henry Hervey Bruce (the grandson). We find Ben McFetridge in Ballymaclary with his family (Margaret, William, Jane, Daniel, and Malcom) in the Census of Magilligan Presbyterian Church in 1855; I also found McFetridge (McLean) in the 1851 census excerpts in Ballymaclary. I don’t think these McFetridges are related to Dennis Hampson; they are merely occupying his old house after his widow (and presumably his daughter’s family as well) were evicted.

In the 1858 Griffiths Valuation, the pub building is shown as held by Peter Lafferty.

The house is long gone, but we can get a really strong visceral sense of what it was like, because there is a mid 18th century traditional house from Duncrun (about 3 miles south of Ballymaclary), preserved in the Ulster Folk Museum in Cultra. This house was dismantled stone by stone, taken to Cultra, and re-erected in the Museum. My photo below shows the kitchen of this preserved house in the Museum; on the left is the “outshot” bed, in a little niche in the wall. On the right is the table, under the window. The front door is further around to the right. To take this photo, I stood in the connecting door which led through behind me into the second room of the house.

His portraits and appearance

Rev. Samson described Hampson’s physical appearance:

… Since I saw him last, which was in 1787, the wen on the back of his head is greatly increased; it is now hanging over his neck and shoulders, nearly as large as his head, from which circumstance he derives his appellative, “the man with two heads.” General Hart, who is an admirer of music, sent a limner lately to take a drawing of him, which cannot fail to be interesting, if it were only for the venerable expression of his meagre blind countenance, and the symmetry of his tall, thin, but not debilitated, person.

Rev. G. Sampson, Wed 3rd July 1805, letter to Sydney Owenson, published by her in The Wild Irish Girl 1806 [3rd edition 1807 vol 3 p103]

“Limner” is an old word for a portrait painter. So it seems that General Hart commissioned a portrait painter to go to Magilligan to paint a portrait of Dennis Hampson, perhaps in around 1804-5. I do not know if this portrait still exists or not. I have heard rumours of a painting of Hampson in private ownership; a concert programme produced by Limavady Borough Council for his bicentenary on Saturday 10th November 2007 says “A painting exists, apparently of O’Hampsey at his bedside with a harp …”

We do have three other portaits of Dennis Hampson. Two of them are pencil drawings attributed to Brocas, and said to be of Hampson. They are both very similar, showing an elderly man playing the harp to a group of children. Neither is at all realistic; the hand positions are wild and romantic, and the harp is very sketchy, but you could imagine it might be based on the Downhill harp. One has pencil lettering at the bottom that I can’t make out. You can see them both online at the National Library of Ireland: PD 2127 TX 15 and PD 2092 TX 28.

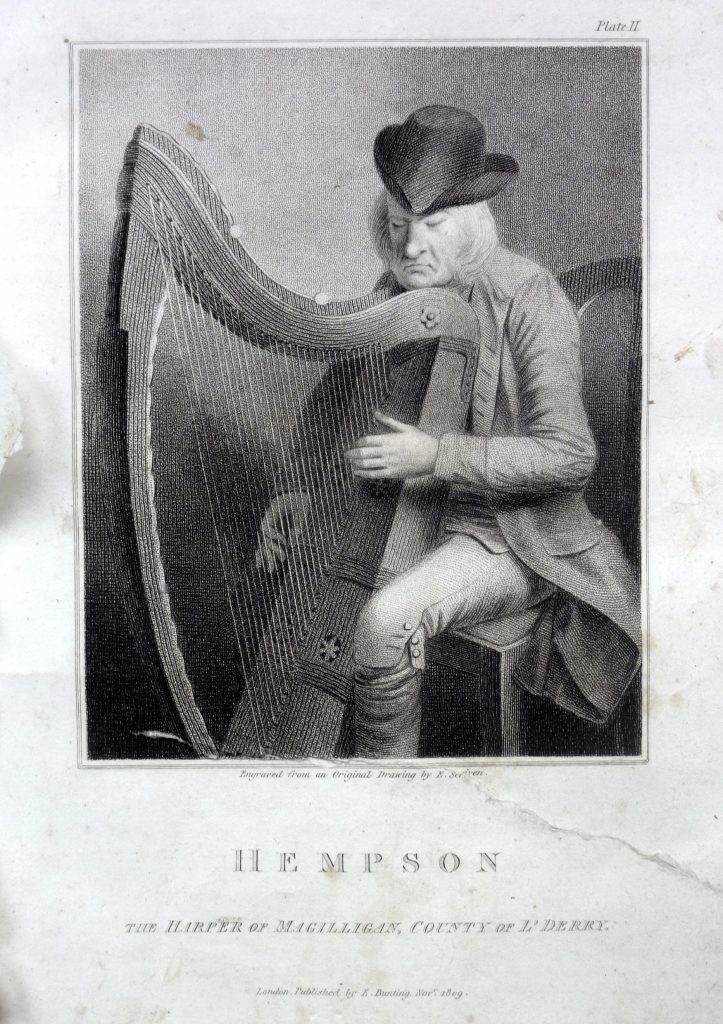

The best know portrait of Dennis Hampson is a stipple engraving which was published in Edward Bunting’s 1809 General Collection of the Ancient Music of Ireland facing page 1. The engraving is captioned “Engraved from an Original Drawing by E. Scriven / HEMPSON / THE HARPER OF MAGILLIGAN, COUNTY OF L’DERRY / London, Published by E. Bunting, Novr. 1809.” A footnote on page ii describes it as “a portrait of Hempson, taken in 1797, Plate II”. Now the problem here is that I am suspicious of the dates given by Bunting in his published books; his memory and his filing system both seem a bit wayward. But it is possible that Bunting had an artist go to Magilligan in 1797 to make the portrait, and then had Edward Scriven do the engraving of it in London in 1809, after Hampson had died. I do not know if the drawing which this engraving is based on still exists.

The harp in the engraving is obviously the Downhill harp (see below); in the engraving it is missing the carved head, but on the harp itself you can see that there is a join or break where the head has been re-attached.

Summarising his life from 1792 to 1809

It is tricky to go through what Dennis Hampson was doing for this period, mostly because I think he had stopped working and travelling and was living at home in his house in Magilligan. We have a couple of anecdotes about him playing out, but I don’t know how to narrow down the time period they refer to, whether they might refer to before or after our study period begins in 1792. But we can look at them anyway.

In 1905, the old people in Magilligan told Walkington

He was only here in summer; in winter he was in Belfast and Dublin ‘playing before the quality,’ and was often at Downhill Castle playing for Sir Henry Bruce

Ulster Journal of Archaeology xii 3 p103)

But it is hard to know how seriously to take this, or what period of his life it might apply to. These reminiscences were from 100 years after he had died.

We also have information from William J O’Neill Daunt in 1846, who describes a tune in his novel and says in a footnote

The description I have here given of the air called “The Elevation,” is derived from an account of it which I received from a venerable relative of mine, in whose Hall, in the north of Ireland, it was frequently played by Denis Hampson, the last Irish harper.

William J O’Neill Daunt, Hugh Talbot: a tale (1846) p436

I don’t know who William J O’Neill Daunt’s “venerable relative” might have been – perhaps Frederick Hervey, or perhaps Henry Bruce, or perhaps another aristocrat in another house? And I don’t know how to date this anecdote.

We also have a nice reference to him playing at home while wealthy people listened from outside:

He had a great habit of playing at night, ‘as the dark made no differs to him’; and Maginnis told us that his father remembered two or three or more carriages standing outside his cottage at night without his knowledge, while the occupants listened to his music.

Letter from L. A. Walkington, published by F. J. Bigger, Ulster Journal of Archaeology xii 3 p103).

Walkington tells us that Maginnis was 97 years old in 1905, and lived about half a mile from the site of Hampson’s house. He may be Hugh McGuinness who died on 21 May 1906 aged 86, and who lived at Woodtown, Benone. So Maginnis would have been born in about 1807-8, about the time that Hampson died (or perhaps a decade later even if we don’t believe the age given); and so his father must have been remembering Hampson playing at home in the 1790s or early 1800s.

Anyway we can work through our references step by step to try and tell a coherent narrative.

Going to Belfast, July 1792

We know that Dennis Hampson travelled to Belfast in 1792, to go to the famous meeting of the harpers on 10-13 July of that year. We have his name in a contemporary newspaper, which I think is the first time he is mentioned in the written records.

… The following is the order in which the Harpers played – and the particular airs chosen by each, in contending for the premiums which are to be adjudged on Saturday:

Belfast News Letter, Fri 13 Jul 1792 p3

DENNIS DEMPSEY, (blind) from the county of Derry, aged 86

Played – The Dawning of the Day – Carolan.

Ul a Condo Wo } Authors and dates

The County of Leitrim } unknown.

… [followed by the names and tunes of the other harpers present] …

(There is a referencing issue with this newspaper; the masthead at the top of page 1 gives its full reference: “From TUESDAY July 10, to FRIDAY July 13, 1792”. Sometimes you will see the same issue referenced as “Tue 10 Jul 1792”)

The meeting of the harpers in Belfast in 1792 is well enough known, and books and papers have been written about the planning, preparation, and events that happened then.

Sampson describes how Hampson himself remembered the Belfast meeting. The account of being in Belfast was prompted by him playing tunes for Sampson, or at least remembering the tunes that Sampson liked:

… Cualin, The Dawning of the Day, Elleen-a-roon, Ceandubhdilis, &c. These, except the third, were the first tunes, which, according to regulation, he played at the famous meeting of harpers at Belfast, under the patronage of some amateurs of Irish music…

Rev. G. Sampson, Wed 3rd July 1805, letter to Sydney Owenson, published by her in The Wild Irish Girl 1806 [3rd edition 1807 vol 3 p104]

“Amateurs of Irish music” I think means “lovers of Irish music” and refers to Dr. James McDonnell and the other Gentlemen who organised the meeting. I don’t know what the “regulation” refers to; perhaps the Gentlemen laid down specifications as to what tunes were to be played or in what order.

The only tune in common between these two lists is “The Dawning of the Day” and we are told in the newspaper that this is a Carolan tune. There are lots of tunes of this title but we have a tune under this title that was transcribed live from Hampson’s playing by Edward Bunting at some point in the 1790s.

I think it is clear that the journalist was working from dictation or from writing what he heard. “Ul a Condo Wo” is a fair phonetical approximation of the tune title of Uilleacán Dubh O. I have already written up the live transcription of the dots of the tune which was written from Hampson’s playing by Edward Bunting, probably four years later in 1796.

Bunting obviously thought that “the County of Leitrim” was an alternative title for “Uilleacán Dubh O” because he uses it as a second title in some of his piano arrangements in in the mid 1790s (e.g. QUB SC MS4.33(3) p.22 “Uillegan Dubh Ó or County Leitrim / From Dennis a Hempson of Maggilligan”). Yet the newspaper seems to think they are two different tunes, because it brackets them together and says “authors and dates unknown”.

Ceann Dubh Dílis is a very nice tune, but I don’t know of a version taken down from Hampson by Edward Bunting.

The Coolin was a “standard” in the old Irish harp tradition. I wrote up some information about different versions or variants, and different titles. It is not clear to me exactly what version Dennis Hampson played in Belfast.

We also have a review of the harpers meeting

The Harpers were assembled in the Exchange-Rooms, and commenced their probationary rehearsals on Wednesday last, and continued to play for about two hours each succeeding day till Saturday; – after which the fund, arising from subscriptions and the sale of tickets, to a considerable amount, was distributed in premiums (or donations) from ten to two guineas each, according to their different degrees of merit. The highest premium was adjudged to CHARLES FANNING, (from the county of Cavan,)…

The Northern Star Wed 18 Jul 1792, reprinted in the Dublin Evening Post, Sat 21 Jul 1792 p3

This review also includes a longer list of tunes but doesn’t say who played each one.

Much later on, Edward Bunting published information about the 1792 meeting, but as far as I can see he was just copying information from these two newspaper articles.

We have independent information from the harper and tradition-bearer William Carr, who was at the meeting in Belfast in 1792 and who played a tune there. In 1807, he reminisced to an English visitor about the meeting and the harpers, and the English man wrote the information down in his notebook.

… Dennis Hampton Co Derry. Man mentioned by Miss Owenson, he did not play so very well as some and was then very old. …

ed. Angela Byrne, A Scientific, antiquarian and picturesque tour – John (Fiott) Lee in Ireland, England and Wales, 1806-7. Routlege 2018, p.303

I think this is very valuable as an insider’s opinion on Hampson’s music. It is not clear to me if the “mentioned by Miss Owenson” comes from Carr; more likely it is Lee’s insertion; I presume he would have read The Wild Irish Girl as soon as it came out in 1806. Carr tells us how much some of the harpers got as their premiums, but he doesn’t say how much Hampson got.

We seem to have a couple of later traditionary accounts of Dennis Hampson going to the Belfast meeting, remembered by people in Magilligan long after his death.

On 25th May 1835, John Bleakly collected information from Dennis Hampson’s daughter, Catherine McKeever, and also from two local farmers, John Moody and John McCurdy. He reported:

At a concert in Belfast Dennis obtained £12

typescript via Ann and Charlie Heymann; see also Ordnance Survey Memoirs… vol 11, 1991, p129

Again I assume this refers to the Belfast Harp Festival in 1792, though the amount seems excessive; Carr tells us that Fanning got 10 Guineas (£10 10s) for first prize. and Quin got 5 Guineas (£5 5s) for second prize (Byrne 2018 p303).

In 1905, Walkington interviewed old people in Magilligan and his report (edited by F. J. Bigger) says:

There is a tradition that O’Hampsay won the first prize for playing the harp at a competition in Dublin, and the tune that he played on that occasion was ‘Molly Asthore.’

Letter from L. A. Walkington, published by F. J. Bigger, Ulster Journal of Archaeology xii 3 p104).

I am assuming this is a garbled memory of Dennis Hampson going to the Belfast meeting in 1792, and not an accurate record of some other meeting that we don’t otherwise know about. I wrote up the different sources for this tune, which is best known today under its Thomas Moore song title, “The harp that once through Tara’s hall”.

I think Hampson must have travelled straight back from Belfast to Magilligan.

Edward Bunting’s visits, 1792 & 1796?

Edward Bunting talks a lot about Hampson in his later published books, but it is hard to disentangle the facts from his opinions, and from his recycling of other written sources (Sampson and the newspapers). Bunting had been employed as a literate classical musician to attend the meeting of harpers in Belfast in July 1792, to write down their music, so that it could be arranged for piano and published. It is not at all clear to me what, if anything, Bunting actually wrote at the meeting; there are hints that he may have tried to transcribe the playing of some of the harpers. But after the meeting finished Bunting seems to have felt the need to travel out into the countryside to collect more or better versions of tunes he had heard or attempted to transcribe in Belfast. I discussed this at length in my post on Bunting’s collecting trips.

Edward Bunting seems to have gone to Magilligan to visit Dennis Hampson at home in the summer of 1792, and tried to write down some of Hampson’s tunes direct from his performance. Bunting used some of these live transcription dots to develop into classical piano arrangements for his Spring 1796 proof sheets.

It appears that Bunting also went again to Magilligan in the summer of 1796 to make live transcription notations of more tunes from Hampson’s playing. He used some of these to make more classical piano arrangements, and finally published his first volume of Irish music in 1797.

Henry Joy McCracken mentions another trip to Magilligan that his brother John, and Edward Bunting, seem to have been planning, at the end of 1797. I am not finding any tunes tagged as being collected from O’Hampsey in 1797 or 1798. This would have been after the published book was finished. But this letter strongly suggests that Bunting was at least planning a trip to visit Hampson in Magilligan in the winter of 1797-8.

I hope John & Bunting will have a pleasant trip to Magilligan

Henry Joy McCracken [Kilmainham Gaol, Dublin] to Mary Ann

I wish much that I could have been with them.

McCracken [Belfast], 28 November 1797, printed in Cathryn Bronwyn McWilliams, The letters and legacy of Mary Ann McCracken (1770-1866), Åbo Akademi University Press, 2021 p.402, letter 41

Unfortunately Bunting did not keep any kind of diary or journal about these collecting trips; his statements about them are incredibly vague and uninformative, and his field notebooks are a disorganised muddle, so it is very difficult to untangle what tunes and information he got from which informants when and where. They tell us a lot more about Bunting’s classical music arranging project than they do about his traditional informants. Bunting wrote a lot about Dennis Hampson in his 1840 published book, but it does not tell us much about Hampson’s life or him as a person. If you want to read more about Bunting’s work collecting tunes you can check out my Old Irish Harp Transcriptions Project.

I don’t think it is possible at this stage to make a definitive list of what tunes Dennis Hampson played for Edward Bunting in the 1790s, because Bunting did not keep proper records, but (as well as those mentioned above) some tunes that Bunting likely did collect from Hampson and which I have written up include Féachain Gléis; Dawn of Day; True love is a tormenting pain; Cad é sin do’n té sin nach mbaineann sin dó; Lady Letty Burke; Codladh an tSionnaigh; Tá an Samhradh ag teacht; Maidin bhog aoibhinn; Eleanor Plunkett; The Parting of Friends; Codladh an Óigfhir; plus others that have more dubious or speculative associations with Hampson.

Bunting also tells us that he collected information about technical terms or fingering techniques from Dennis Hampson, though we don’t have his working notes of this, only his synthesised edited and re-interpreted summary tables. He says “The harpers whose authority was chiefly relied on were Hempson, O’Neill, Higgins, Fanning, and Black…” (Bunting 1840 intro p20). He also says “Although educated by different masters, (through the medium of the Irish language alone,) and in different parts of the country, they exhibited a perfect agreement in all their statements” so I don’t think it is possible to untangle which of the different traditional harpers he collected which parts of the technical information from. The best we can say is that at some stage, Bunting appears to have collected some technical information from Dennis Hampson.

Patrick Lynch’s visit, 1803

The song-collector Patrick Lynch was in Magilligan in March 1803, and he collected some song lyrics from Dennis Hampson.

Lynch had been commissioned by Edward Bunting to collect song lyrics in the West of Ireland, and the two had went to Castlebar and Westport in May – June 1802. This trip is fairly well documented in Lynch’s diary and letters. But there has been less study of Lynch’s trip to Magilligan. I have found a couple of manuscript sheets in Bunting’s papers which Lynch wrote in Magilligan. There may be more.

Queen’s University Belfast, MS4.26.46 is a pamphlet which looks like it may be Patrick Lynch’s field notebook from his visit to Magilligan. It contains the cursive text of a number of song lyrics, and it finishes with a list of elderly people living in Magilligan, dated 17th March 1803.

The first twelve pages (MS4.26.46a through to l) are song texts with occasional jotted information around them. The next ten pages (m through to v) are blank; and the final two pages (w and x, written from the back I think) are the list of names. There are 29 names of people aged from 66 to 100, mostly round numbers (i.e. not exact ages). One of the names is “Dinnis a hampsy of Ballymaclary – 100”. The next is “his wife Nanny Dougherty – 66”. The list is headed “Living all within a mile in a part of the parish of Magilligin”.

So this rough pamphlet does not give us any attributions or sources for the song texts, but we have a neater copy of the songs which does.

QUB SC MS4.26.2 is a 12 page pamphlet written out neatly by Patrick Lynch. It countains neat presentation copies of some of the songs from the rough pamphlet, and some of them contain source attributions. MS4.26.2.a (the 2nd page of the pamphlet, inside the front cover) has a list of three song titles headed “dinnis hampsy of Magilligan”; the three titles are “Molly Stuart”, “Molly St george” and “hob nob”, all written in English in neat italic script. There is a second list of five tunes headed “Rose of Innis eon”; her titles are written in Irish in neat Gaelic script.

MS4.26.2b (the third page of the pamphlet) has the text of “Molly Stuart”. The title is in English written in italics, but the four verses of lyrics are written in Irish in Gaelic script, beginning “Gasda shligh luaimneach…”. The page is headed “From Dennis Hampson a harper of Magillagan aged 100 years”. The next page, MS4.26.2c has the title “Molly St George” and Irish lyrics beginning “Is an inghion sin san seoirse…” and the tag “from Dennis Hampson”. The lyrics continue onto the following page (which does not seem to have a library reference letter).

Then on the 6th page of the pamphlet (MS4.26.2d) is another song lyric. It is titled “hob nob” in Gaelic script, and tagged “D[?]nnis Hampson”, and the text begins “A sheamuis brún…” I think this lyric may be connected to the tune of Diarmaid Ó Dúda which Bunting collected from a harper in the 1790s.

Then follows five song texts without tags, but which match the five titles attributed to Rose of Inishowen at the start of the pamphlet.

Then finally the back page of this neat pamphlet (MS4.26.2.j) is titled “fragments from Dennis Hampson”, and there are three little fragments. The first is four lines of poetry, titled “a chailinigh bhfaca shibh seorse” which obviously relates to the harp tune of the same title that Bunting collected from Hampson (discussed a little in my write up of a different version of this tune). The next is two lines, titled “The dying lover” and beginning “nach truaigh leatsa a staidbhean…”, and the third is a single line, titled “saebha gheal ni granda” and reading “Rachainse leat ar saile a nunn”.

George Sampson’s visit, 1805

Sydney Owenson, later Lady Morgan, was a novelist at the beginning of the 19th century, who also played the classical harp. When she was writing her romantic novel The Wild Irish Girl she wrote letters to a number of different scholars and antiquarians asking questions about Irish history and culture, to use as resources for her novel. She printed some of the information they sent her as footnotes to the novel.

She wanted to find out information about Dennis Hampson for the novel, and so she wrote to Rev. George Vaughan Sampson (1763–1827) asking him to find out more information. Samson went to visit Dennis Hampson in his cottage in Magilligan on Tuesday 2nd July 1805, and he wrote up the information in a letter to Lady Morgan the next day, Wed 3rd July 1805. When the novel was published in 1806, Samson’s letter was printed as a very long footnote which continues over a number of pages of the novel. I have not yet seen a true first edition, but you can see an early edition online at Google Books.

Sampson’s text is our main source for Hampson’s youth and career, which is not relevant to this post; it also has some useful information about Hampson’s activities between 1792 and 1805 which I have already quoted. But it also has some on-the-spot observations about what happened on Tuesday 2nd July 1805:

…I found him lying on his back in bed near the fire of his cabin; his family employed in the usual way; his harp under the bed clothes, by which his face was covered also. When he heard my name he started up (being already dressed), and seemed rejoyced to hear the sound of my voice, which, he said, he began to recollect. He asked for my children, whom I brought to see him, and he felt them over and over; – then, with tones of great affection, he blessed God that he had seen four generations of the name, and ended by giving the children his blessing. He then tuned his old time-beaten harp, his solace and bed-fellow, and played with astonishing justness and good taste.

Rev. G. Sampson, Wed 3rd July 1805, letter to Sydney Owenson, published by her in The Wild Irish Girl 1806 [3rd edition 1807 vol 3 p103]

The tunes which he played were his favourites; and he, with an elegance of manner, said at the same time, I remember you have a fondness for music, and the tunes you used to ask for I have not forgotten, which were Cualin, The Dawning of the Day, Elleen-a-roon, Ceandubhdilis, &c.

We have a version of Eibhlín a rún which Edward Bunting had collected from Dennis Hampson in the 1790s, though it is not a live transcription “dots” of his harp performance but a neater re-copying, which is why I never wrote it up as part of my Transcriptons Project. You can see Bunting’s field notebook with this tune here at Queen’s. The other tunes are the ones he said he played in Belfast, and I already mentioned them above, but here are links to my write-ups again of The Coolin and Dawn of Day.

Sydney Owenson almost visiting, 1806

Sydney Owenson described a visit to Dennis Hampson at his house in Magilligan in her novel The Wild Irish Girl. The episode of the visit is vividly written in the first person, and so people often assume that she herself went there. However, the text is fictionalised and is actually written as the first-person narrative of the novel’s hero, Horatio. This episode in the novel is clearly derived from George Sampson’s letter describing his actual visit in 1805 (which she prints as a footnote) and so I don’t see any reason to suppose that Owenson herself made a visit to the house, especially since when she tells us in her footnote that she was in the neighbourhood, she does not mention actually visiting.

In February, 1806, the author, being then but eighteen miles distant from the residence of the Bard, received a message from him, intimating that as he heard she wished to purchase his harp, he would dispose of it on very moderate terms. He was then in good health and spirits, though in his hundred and ninth year.

Sydney Owenson, The Wild Irish Girl 1806 [3rd edition 1807 vol 3 p107]

It is not clear why he would want to sell his harp; unless he had basically stopped playing by then. But his obituary (see below) seems to imply that he was still performing up until his death. Unless of course it was a second harp that he was offering to sell. We will discuss the second harp later.

Death

According to his obituary, Dennis Hampson died on 5th November 1807.

On the 5th inst. at the advanced age of 110 years, DENIS HAMPSON, the blind bard of Magilligan, Ireland, of whom so interesting an account is given by Miss Owenson, in her elegant work, “The Wild Irish Girl.” A few hours before his death he tuned his Harp, in order to have it in readiness to entertain Sir H Bruce’s family, who were expected to pass that way in a few days, and who were in the habit of stopping to hear his music; shortly after, however, he felt the approach of death, and calling his family around him, resigned his breath without a struggle, being in perfect possession of his faculties to the last moment.

Belfast Commercial Chronicle, Sat 21 Nov 1807 p3

This may well not be the earliest printing of the obituary text, but it is the earliest I have yet found. Slightly abridged versions were printed in Scottish and English newspapers: Caledonian Mercury Sat 28 Nov 1807, Sun Wed 2 Dec; Public Ledger and Daily Advertiser, Thur 3 Dec; Ipswich Journal, Sat 5 Dec; Hereford Journal, and Aberdeen Press and Journal, Wed 9 Dec; Derby Mercury, Thur 10 Dec; Lancaster Gazette, Northampton Mercury, and Oxford University and City Herald, Sat 12 Dec; and I am sure others as well. Interestingly the English papers don’t give the date of death, but just say “Lately… in Ireland”.

We have a traditionary account of his last moments, collected in 1905 from old people who lived in Magilligan; they would have been born around the time that Hampson died and so this information must come from their parents. I don’t know how reliable this information might be.

On the day he died he seemed to be unconscious for some hours; but about an hour before he died, he opened his eyes wide, and showed ‘two beautiful black eyes,’ which no one had ever seen before, as he always kept his eyes closed. They thought he seemed to see them, but could not be sure, as he was speechless.

Letter from L. A. Walkington, published by F. J. Bigger, Ulster Journal of Archaeology xii 3 p103-4).

Walkington also reported the old people’s information on Dennis Hampson’s burial place (by “authorities” I think he means the old people he was interviewing):

All authorities agreed that he was buried at Tamlacht Ard churchyard … We spent a long time exploring the graveyard, but it is very much neglected, and we could find no trace of his grave, and not even the parish priest had ever heard his name…

Letter from L. A. Walkington, published by F. J. Bigger, Ulster Journal of Archaeology xii 3 p105).

Now we instantly have a problem here because there are two Tamlachtard churchyards, the Church of Ireland one and the Catholic Church one. Walkington does not tell us which the old people were referring to in 1905. The implication is the Catholic one, since they asked the parish priest. But the information from the old people seems a bit unreliable in general so I am wondering how we could tell which one is correct? Unfortunately the burial records for both the Church of Ireland and the Roman Catholic church are missing for our period.

The old church of Tamlachtard is dedicated to St Aidan and is the Catholic church. It was, as usual, confiscated by the Church of Ireland at the Reformation, but Frederick Hervey when he was (CoI) Bishop of Derry was very liberal and allowed Catholics to use it for burials. Eventually, Hervey had a new Church of Ireland church buit about a mile to the north-east, around the 1770s and 1780s. Once the new St Cadan’s CoI was built, Hervey gave the old church and burying ground to the Catholic congregation.

The old church is ruined, but a new Catholic church was built right next to it in 1826. Apparently the old church should also be St Cadan (who was a disciple of Patrick), but over the centuries the name has become garbled into Aidan. There is a rough stone tomb outside the east wall of the ruined old church that is said to be St Aidan’s tomb, and there is a holy well nearby as well.

In 1837 the old churchyard was described as “being the burial-place of most of the old families of every religious persuasion” (Topographical dictionary of Ireland vol 2 p590-2), and people have been assuming that it was the old churchyard where Dennis Hampson was buried. In 1998, Limavady Borough Council installed a small but handsome memorial slab close to the ruins of the old church.

The Downhill harp

The harp which Dennis Hampson played on apparently from when he started work as a professional in the early 18th century, right through until his death in 1807, is preserved and displayed in the Guinness Storehouse museum in Dublin. It is now known as “the Downhill harp”. It has 30 wire strings, and it is a fairly small traditional wire-strung Irish harp, smaller than most of the harps played by his contemporaries and smaller than the traditional wire-strung harps used through the 19th century. I always think it is a good model for children or small people to use; yet Sampson describes Dennis Hampson as being “tall”. I’m not sure how to quite understand this, if he was stooped because of the lump on the back of his neck, or if Sampson was exaggerating “the symmetry of his tall, thin, but not debilitated, person”.

The Downhill harp is a very interesting instrument, signed by the famous harpmaker Cormac O’Kelly, and dated 1702. A number of harpmakers have studied it as part of making new copies, and these copies tend to work well as practical musical instruments and are often recommended for people wanting to learn and play the traditional wire-strung Irish harp. Unfortunately there is not a good published technical analysis of it.

It was already an antique, over 90 years old at the start of the time period we are interested in (post-1792). Sampson describes it as “his old time-beaten harp”, and because for obvious reasons most technical study of it focuses on its design, construction, and early provenance, it is outside the scope of my Long 19th Century Project. So we are not going to do any technical study of it here.

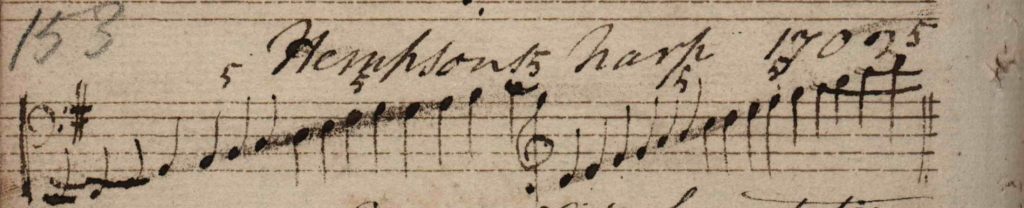

However, one aspect of the Downhill harp that we can consider is the tuning schedule for this harp, since our source for the tuning of the harp comes from after 1792. Edward Bunting, presumably on one of his visits to Magilligan in the 1790s, wrote down a scale of notes headed “Hempsons harp 1702”. This is a very valuable description of how a traditional Irish harp was tuned by a tradition-bearer at the beginning of my “long 19th century” (1792-1809).

Bunting printed this same scale in his Ancient Music of Ireland (1840) p.23, along with the tuning cycle used to set all the strings of the harp in tune, and a detailed commentary on different traditional tunings. I don’t know if the cycle and commentary is also derived from Dennis Hampson’s information, or not. As part of my Transcriptions Project, I wrote up the information about some of the sources for traditional tunings.

Edward Bunting tells us:

…His harp is preserved in Sir Henry’s mansion, at Downhill…

Edward Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland, intro p.76

We have already mentioned Dennis Hampson’s two successive landlords who lived at Downhill House: Hampson’s patron, Frederick Augustus Hervey, 4th Earl of Bristol and Bishop of Derry (1730-1803), and Frederick’s cousin who inherited in 1803, Rev. Sir Henry Hervey Aston Bruce, 1st Baronet Downhill (d. 1822).

When Henry Bruce died In 1822, he was succeeded by his son, Sir James Robertson Bruce, 2nd Bt (1788-1836). When James died in 1836, the house and title were inherited by his own son, Sir Henry Hervey Bruce, 3rd Baronet (1820-1907). This must be the man named by Bunting; but because both he and his grandfather are called Sir Henry Hervey Bruce you can see how Bunting has got confused. I was confused too until I laid it all out like this!

I already mentioned above, the account of how the harp came to be at Downhill house. This is from a text criticising Henry Bruce the cousin for his meanness and lack of culture, and says how

… he not only deprived the old widow of Denis Hampson of the cottage, which the Earl had bestowed on the minstrel, but actually carried off the harp for arrears of rent.

The Irish Shield and Monthly Milesian, Vol 1 no ix, September 1829 p351

So Dennis Hampson’s old harp went to Downhill House some time between 1807 and 1829, and from then on it became known as the Downhill harp. It was presumably there when the house burned in 1851, but it was obviously saved from being damaged then. I have seen a photograph of the harp in the basement of the house (I think this was the entrance hall after the late 19th century re-modelling of the house). Mike Billinge found the references to its sale at an auction of the contents of Downhill House (presumably this was the Christie’s sale on 16th June 1950 though I have not been able to find a sale catalogue), and its subsequent purchase in 1963 by Guinness, who own it now; it is on display in the Guinness Storehouse Museum in Dublin.

The Harp of Hempson

There is a second harp which is said to have belonged to Dennis Hampson. I think the earliest reference to it is from 1852 when it belonged to Mr E Lindsay of Belfast, who exhibited it in Belfast as the harp of Hempson. Lindsay also exhibited another harp he also owned, which was described as the harp of O’Neil. Mike Billinge has written a long analysis of the O’Neil harp, defending its traditionary association, but he does not deal with the Harp of Hempson. Robert Bruce Armstrong similarly did not pay any attention to it; he describes it as “the drawing-room instrument of the Sheraton period, also in the Belfast Museum” in his 1906 book, p88, and mentions it again on p105 where he says it “is of little consequence”.

The two harps were loaned to the Feis Ceoil exhibition in Dublin in 1899 (Irish Independent, 17 May 1899 p4). By 1907, Both harps (O’Neil and Hempson) belonged to the Belfast Natural History and Philosophical Society, who loaned them for the Irish International Exhibition, Dublin 1907. The Belfast Society agreed to give its collections to the Belfast Museum in 1910; and the two harps now belong to National Museums Northern Ireland. The Harp of O’Neil is on display in the public galleries of the Ulster Museum, Belfast, with the registration number BELUM 0391.1911; and the Harp of Hempson is in storage with the accession number BELUM 0390.1911.

I went to the Museum storage facility last year and inspected the Harp of Hempson. It looks to me like it may have been made around 1800 or in the early years of the 19th century. It is constructed with a staved back, a cross-grain softwood soundboard, and a straight cylindrical pillar, yet it appears to have been designed and set up as a traditional wire-strung Irish harp. The neck has scars where the brass cheek-bands were removed, and one traditional-style tuning pin remains. It looks like there are fragments of brass wire remaining in the soundboard. It has a paper label stuck on the back, reading “Belfast Nat. Hist. & Philo. Society. / Harp of Hempson.” and a second paper label reading “The harp of Hempson / Belfast Museum”.

At the moment I don’t know what to think about this harp. It looks to me like a working traditional wire-strung Irish harp. But there are so many questions. Do we believe it has some kind of connection to Dennis Hampson, and if so what might that connection be? Could this be the harp that Hampson offered to sell to Sydney Owenson in February, 1806?

If we don’t believe the association with Dennis Hampson, then we have to explain where the association came from, and we also have to explain what the harp actually is. At the moment I am vaguely wondering if this harp may be associated with the Irish Harp Society school which Arthur O’Neil taught in Belfast between 1808 and 1812, but it may have no connection to those traditional harpers at all. At the moment I really don’t know.

I think this instrument deserves a much more in-depth close study. I think a 3d-scan should be done, and an accurate reconstruction copy should be made, so we can find out how it works and how it fits into the wider tradition. We could start this project at once; we just need someone to fund it.

His legacy: teaching

The most important way that a traditional musician can leave a legacy, is by teaching, by passing on their inherited tradition to the next generation of players. Dennis Hampson did not do that, and we don’t have any references to traditional harpers who learned to play from him.

Well before our study period (1792-1909) there is a reference to Hampson being asked to teach, when he was touring in Scotland in the mid-18th century; but he never went back to take up the invitation. (Rev. G. Sampson, Wed 3rd July 1805, letter to Sydney Owenson, published by her in The Wild Irish Girl 1806 [3rd edition 1807 vol 3 p100])

More relevant to us, is Sampson’s comment, from 1805:

I asked him to teach my daughter, but he declined; adding, however, that that it was too hard for a young girl, but that nothing would give him greater pleasure, if he thought it could be done.

Rev. G. Sampson, Wed 3rd July 1805, letter to Sydney Owenson, published by her in The Wild Irish Girl 1806 [3rd edition 1807 vol 3 p105]

I do have one enigmatic reference. It is a marginal annotation in a copy of Edward Bunting’s Ancient Music of Ireland (1840), which belonged to belonged to James P. Sherwin (1871- 1960), a Catholic priest in Dublin. On p.6 of the preface, beside where Bunting describes visiting Hampson, Sherwin has written:

Patrick

tolLangan

my very old teacher

a pupil of Hempson

told me

He plucked the

strings with his

long nails

J P Sherwin

I wrote a post about this annotation, trying to work out what was going on. It seems most likely that Patrick Langan was Br. Patrick Leo Lanigan / Lannigan (1848-1933), who was principal of the James St. School from 1880 to 1905. Sherwin was born in 1874 and went to the James Street school, so surely would have studied under Br. Lanigan. But Lanigan is far too young to have been “a pupil of Hempson”, and would only have been 32 years old in 1880, hardly “very old”. So this does not really add up.

I think Dennis Hampson’s legacy is much more as an icon or symbol to be held up as the last harper. This is a very old trope; even before Carolan’s time, people were talking about the Irish harp tradition coming to an end. Carolan was widely held up as the last bard. And after Hampson’s time, we have a whole series of people being labelled as the last of the harpers, perhaps most obviously Patrick Byrne.

His legacy: becoming famous

Dennis Hampson’s fame seems to come primarily from Edward Bunting. I think that we can analyse Bunting’s work as fitting into a late 18th and early 19th century world-view, which simultaneously combined the idea of society and culture declining from a lost golden age in the deep past, and also the idea of scientific progress towards modern perfection. From this point of view, Bunting would want to find the most ancient strands of Irish musical culture, and then to re-fashion them in “modern” (i.e. classical) style piano arrangements for a middle-class cosmopolitan audience.

To Edward Bunting, Dennis Hampson clearly represented an earlier generation of the tradition, and we see this being exaggerated in the ever more ambitious claims for his age. Bunting seized on the way Hampson played with long fingernails, as a kind of icon of his ancientness; and Bunting made a big fuss over the way that Hampson would play more ancient repertory, that (he claimed) none of the other harpers knew. I am fascinated by how Bunting concentrated so much on Hampson, and totally ignored the youngest of the harpers at Belfast, William Carr. Later on, Bunting similarly ignored the next generations of harpers; we know he met Patrick Murney in the late 1830s, but pointedly ignored him. And then in 1840 Bunting callously betrayed the tradition-bearers who were still working to continue the inherited tradition, by declaring that tradition dead, and cutting all support and funding from the harp school in Belfast by publishing John McAdam’s deadly letter.

Bunting’s obsession with O’Hampsey’s ancientness, and his declaration that the tradition was dead after the first decade of the 19th century, meant that Dennis Hampson has come to be held up as “the last” of the Irish harpers. Some people take a slightly more nuanced approach, declaring that Hampson was the only “genuine” traditional harper left by 1792. This of course marginalises and disrespects all the other traditional harpers alive at this time and subsequently, especially Arthur O’Neil and Patrick Quin who were not only still out performing but were also teaching the next generation of young harpers. I also think it disrespects Dennis Hampson. By raising him up to be an icon of ancientness, a kind of living fossil who unknowingly preserved fragments from centuries earlier, this kind of attitude downplays him as a person and as a musician of his own time, working alongside his peers in playing and sharing the living tradition.

In fact, my entire Long 19th century project, to document and tell the stories of the traditional harpers who were active all through the 19th century and into the first decade of the 20th century, can be seen as a revision of this old trope of Hampson being the last of the old harpers. I think it is important to look beyond the grandiose claims and pedestals, to see Dennis Hampson as one amongst a number of harpers active in the inherited tradition in the 1790s and early 1800s, and to see his death in 1807 not as the end of an era, but as part of a continuing tradition. If we check my timeline, we can see that when Hampson died in 1807, there were at least seven other Irish harpers still alive and working that we know of, playing on full-sized wire-strung Irish harps in the inherited tradition: Charles Byrne, Patrick Quin, Dominic O’Donnell, Arthur O’Neill, William Carr, O’Connor from Tyrone, and Bridget O’Reilly.

And just seven months after Hampson died, Arthur O’Neil was in Belfast starting to teach at his new school there, guaranteeing the continuation of the inherited tradition of playing the wire-strung Irish harp for another century.

Thanks to National Museums Northern Ireland for access to the Harp of Hempson; thanks to Queen’s University Belfast for the ms4.29 page image; and thanks to Ann and Charlie Heymann for sharing insights and documents relating to Dennis Hampson over the past couple of decades.

Oh I do love these articles. Now i want to see the area of the pub and Downhill House!

When you come to Armagh we can go there, its about an hour and a half drive North from here.

Simon, I have had a superficial knowledge of ‘Hampson’ for more than 50 years, but I must say I am blown over by your meticulous historical scholarship.

Many thanks for a great read!

John Williams, Sydney

Brian Audley gives a transcription and drawing of the little gravestone visible in my photo at the head of the 1998 memorial slab, in his book Denis O’Hampsey the harper (Whisper Press, Belfast, 1992), p.12 and plate 1. His transcription of the inscription reads:

He also speculates that perhaps this Mary Hamcy “would appear to be a relative, possibly a grandchild, niece or even a daughter of the old harper”.

I tried to take a 3D photo of the inscription for you but the light was not good (and I didn’t take my big studio lights) so it is not really very legible.

Simon, I have been looking at bits and pieces of Dennis Hampson for years but have never found anything like the amount of information that you have gathered. My family the Hempseys came from Derry in the 1800s to Philadelphia and at that time the surname was Hampsey. I don’t know if I am the same bloodline as Dennis but I have seen family records in the same area where he came from. I always thought that O’Hamsaigh was the original spelling but your timeline makes a lot of sense. I am in Derry City now and am hoping to make it out to Binevenagh to explore the area. Thank you for all of your work! Phil Hempsey

I changed the map link to point to the National Library of Scotland, who have a wonderful online free-to-use digital collection of old Ordnance Survey maps.

Below is a detail from the first edition six-inch map (Co Londonderry sheet 2), which was surveyed in 1831, and engraved in 1832, but not printed until 1837.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, CC-BY

Seacoast Road runs almost North-south; the dotted townland boundary runs east-west along the lane, between Benone to the north and Ballymaclary to the south. Lafferty’s pub, now the Anglers Rest, is on the north west corner of the crossroads (upper left). The cottage which I think is Hampson’s is to the south east of the crossroads (lower right).