Thomas Shea was a traditional Irish harper in County Kerry in the 18th century. He was still alive (though very old) in 1792 and so he gets a place in my Long 19th Century project, about harpers who were active between 1792 and 1909.

Header image courtesy of the National Library of Ireland.

I think we have only three references to Thomas Shea. In this post we will discuss these references, and what they can tell us about him. My focus of course is on what he was doing from 1792 onwards but to be honest that’s about all the info we have anyway!

Edward Bunting’s information

Bunting mentions Shea in his 1840 book. I think this is the earliest published source to mention Shea. It doesn’t tell us very much.

O’SHEA, a County Kerry harper, was born in the same year. He possessed considerable abilities, and was an enthusiast in every thing connected with Irish feeling: extreme debility alone prevented him attending the Belfast meeting.

Edward Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland, 1840, introduction p.78

The “same year” must refer to 1712, mentioned at the end of the previous page. I think Bunting has mis-calculated this year based on the age given in the letter (see below). It seems clear that this information is based on the letter, and perhaps also on Arthur O’Neil’s information.

Arthur O’Neil’s information

The next reference is in a loose sheet of paper, which is connected somehow to Arthur O’Neil dictating his Memoirs to the secretary Thomas Hughes in Belfast in about 1808. The sheet is in Hughes’s handwriting; it includes fragmentary lists of names, and doodle sketches of O’Neil. The sheet came with Edward Bunting’s papers to Charlotte Milligan Fox, but in the beginning of the 20th century she loaned the sheet to F. J. Bigger for an exhibition. It was never returned, and so Fox gave the Bunting manuscripts to Queen’s, but our sheet went with Biggar’s papers to Belfast Central Library.

…

Belfast Central Library, F.J. Bigger Archive, Envelope V6

O’Shea – of Tralee

…

and on the second side:

…

Belfast Central Library, F.J. Bigger Archive, Envelope V6

O’Shea

…

This doesn’t tell us very much, except that Arthur O’Neil knew of a harper called O’Shea, who was based in Tralee. The other two sources don’t mention Tralee, so this is information that Arthur O’Neill got independently (not from Shea’s letter).

Tralee is the county town of County Kerry, situated at the inland end of the Dingle peninsula.

Arthur O’Neil’s mention of him in c.1808 doesn’t even tell us if he was alive or not at that point, since some of the other harpers listed on the same sheet were dead by 1808. I have no information about when Thomas Shea died; he was alive but aged about 84 in 1792. So all we can say at the moment is that he died some time after the summer of 1792.

Thomas Shea’s own information

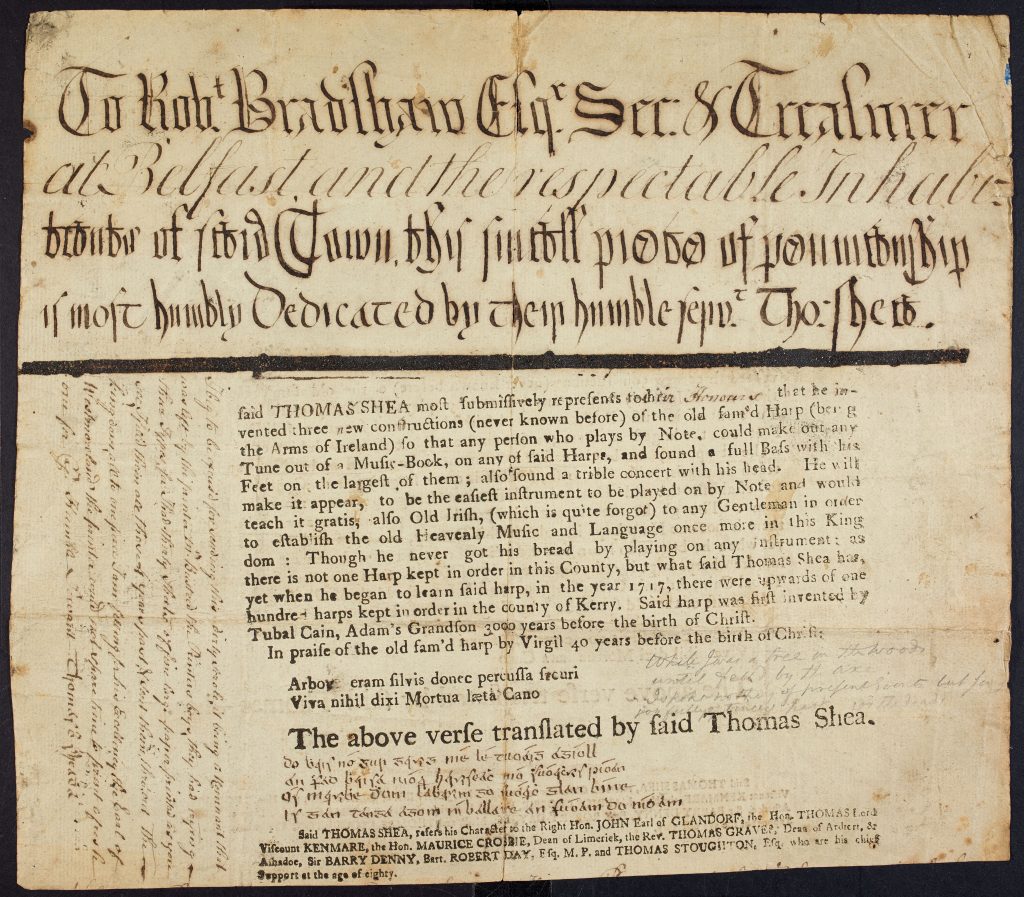

Our main information about Thomas Shea comes from his own hand, in the form of an extraordinary letter he wrote in 1792. The letter is now preserved in the National Library of Ireland in Dublin.

As you can see, there is a lot going on here. A complete transcription and edition of the letter with a very brief commentary was published by Alf MacLochlainn, ‘Thomas O’Shea, a Kerry harper’, in Journal of the Kerry Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol.3, 1970. Part of the printed section of the letter was quoted by Ann Heymann in her book Secrets of the Gaelic Harp (1988) p.12, which is where I first came across Thomas Shea, I think in 1993 when I got a copy of Ann’s book.

We will pick the letter apart to see what it can tell us about Shea himself.

The letter consists of three different layers of text. First of all is the printed text. Then there are handwritten additions by Thomas Shea. And then there is also a later pencil addition (translating the Latin and Irish text) which was put there by someone else, perhaps in Belfast after the letter was received there.

The printed text is fascinating. It is in the form of a kind of standard letter or promotional text, which Shea had printed for him by a local printer. It has spaces left for Shea to fill in the addressee and to show off his handwriting and linguistic abilities.

Shea explains in the handwritten additions that the sheet was printed by Busteed, who was a printer and publisher in Tralee. Shea says the printer’s boys were “trying their types” and printed off “thirty sheets of fine large paper” for him. He says that he “fill’d them all those 4 years past & sent them thro’out the kingdom”, and that he only has this one “remnant” left. It is possible than other copies still exist in the libraries of aristocratic patrons elsewhere in Ireland. We will look in more detail at this handwritten text below.

If the sheet was printed four years previously, and if we assume that the additions were written and the letter sent in 1792, then the printing must have been done in 1788. The printed sheet says that Shea was aged 80, and so we can calculate that Shea would have been born in 1707-8 (if the age given is accurate). We can see that Bunting (or whoever provided the information for the 1840 book) did not read the letter properly, and just subtracted 80 from 1792.

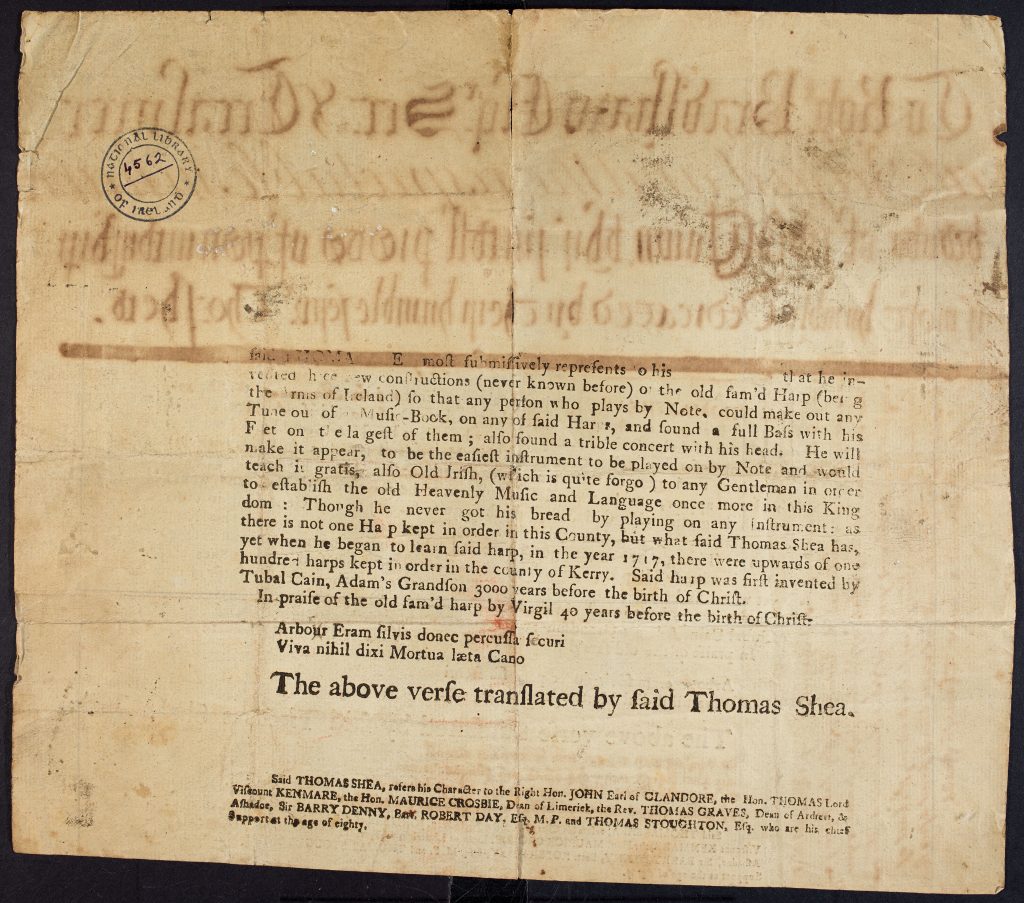

The printed text (1788?)

The sheet is actually printed on both sides. Presumably it was a kind of test or proof sheet before the thirty proper ones were run off. The reverse of the sheet shows us what Shea intended before he had started to write on the printed sheet (if you ignore the ink bleed-through from the display calligraphy). The text is slightly different on both sides, and there are slight corrections and changes from one side to the other. On the unwritten side, the u in “Arbour” has been crossed out in pen; and on the written side the word seems to be printed “Arbor” though the “r” is a bit messy. Also, On the unwritten side, “Aſhadoe” is printed with a long “s” (“ſ”), but on the written side it looks like the paper might have been scraped to try and delete the top of the long s. It should read “Aghadoe”. Also on the unwritten side the letter “e” has been inserted by pen into “s curi”; on the written side there is just a scratchy blob there.

The printed text is a bit odd. It is like an elaborate exaggerated joke, puffing up his own learning and status. Yet it also tells us fragments of real information; it says that Shea started to learn the harp in 1717 (presumably aged about 9 or 10 which sounds about right); that he worked his whole life as a professional harper, making his living from his harp music; and that when he was young there were “upwards of one hundred harps kept in order in the county of Kerry”, but that now he has the only harp in working order in the county.

There are themes here that remind me of how Arthur O’Neil waxed lyrical about the Irish traditions, but I am less sure how to understand the “joke” elements such as playing the bass with your feet and the treble with your head.

At the bottom of the printed text is a list of Shea’s patrons: “the Right Hon JOHN Earl of GLANDORE, the Hon. THOMAS Lord Viscount KENMARE, the Hon. MAURICE Crosbie, Dean of Limerick, the Rev. Thomas GRAVES, Dean of Ardfert, & A[ſ]hadoe, Sir BARRY DENNY, Bart, ROBERT DAY, Esq. M. P. and THOMAS STOUGHTON, Esq.” The only one of these not apparently famous or identifiable enough to have their own Wikipedia entry is Thomas Stoughton.

This is a very interesting list of aristocratic patrons of a traditional Irish harper in 1788. We could usefully compare this with the lists of patrons printed by Arthur O’Neil in his newspaper advertisements for his harp schools in 1793 and 1805; and also with the list of patrons printed in a newspaper advert by Andrew Bell in 1851.

The written text (1792?)

It appears that Thomas Shea wrote the handwritten part of the letter as a response to a newspaper advertisement. In the early summer of 1792, the Belfast Gentlemen placed a whole series of advertisements for their proposed gathering of the harpers. Here is a typical example:

NATIONAL MUSIC OF IRELAND

Dublin Evening Post, Thur 17 May 1792 p2, but reprinted on many other dates in many other newspapers.

☞ A respectable body of the Inhabitants of BELFAST having published a plan for reviving the ANCIENT MUSIC of this Country, and the project having met with such support and approbation as must ensure success to the undertaking – – –

PERFORMERS ON THE IRISH HARP are requested to assemble in this town on the 10th day of JULY next, when a considerable sum will be distributed in Premiums, in proportion to their respective merits.

It being the intention of the Committee that every Performer shall recieve SOME Premium, it is hoped that no Harper will decline attending on account of his having been unsuccessful on any former occasion.

ROBERT BRADSHAW,

Sec. and Treasurer.

BELFAST,

April 26, 1792.

================

NATIONAL MUSIC

The preservaton of our ancient music must appear to be a matter of no small importance to every lover of the antiquities of Ireland. – The encouragement therefore that is held out in our public papers, to procure a numerous meeting of performers on the Irish Harp, at Belfast, on the 10th of July next, when premiums will be distributed according to the merits of the several performers, must give general satisfaction. – The management of this part of the business is intrusted to a numerous Committee of Ladies and Gentlemen of musical skill, who, beside adjudging the principal rewards to the most considerable performers, will also give smaller gratuities to each of the others who shall appear in Belfast on that day.

The premiums are to be confined solely to the native music of Ireland, with a view of reviving such valuable tunes as have fallen into disuse; the judges are instructed to consider the production of such acts of merit as are not to be found in any public collection as a separate claim to the reward, independently of taste, and elegance of execution. Harpers in possession of such pieces, would do well to have them written. – A Gentleman of acknowledged abilities as an Irish scholar and antiquarian, and three musicians of distinguished professional merit, are expected to attend the meeting.

For carrying this plan into execution, advertisements will be immediately published in all the principal News-papers throughout the kingdom. A handsome sum is already received for paying premiums and for defraying the expense, and officers are appointed for conducting the business.

When we think of the British commemoration of a single artist, with what ardour should it inspire us to revive and perpetuate the music of a nation? and may we not expect that Gentlemen throughout the kingdom will encourage Harpers to attend, and that the Printers of News-papers will disseminate this information.

I imagine that Thomas Shea saw a copy of this advertisement, perhaps in a Kerry newspaper, or perhaps in a Dublin paper brought down to Tralee. He would have been thrilled to know that there was a revival of interest in the harp music, and he would have been also excited to see that an Irish language scholar would be there (though they didn’t show up on the day).

Unfortunately for him, however, Tralee is 420km from Belfast, pretty much as far as it is possible to go within “the kingdom” of Ireland; it is certainly the furthest distant county town from Belfast. (Crow Head at the tip of the Beara peninsula is 520km, but I wouldn’t expect to find a harper reading the newspaper there).

If we assume Thomas Shea would travel on foot, it would take 2 to 3 weeks of walking to get there. And he was 84 years old, so there’s no way that was going to happen. So he wrote his letter to the Secretary, Robert Bradshaw, whose name was at the bottom of the notice.

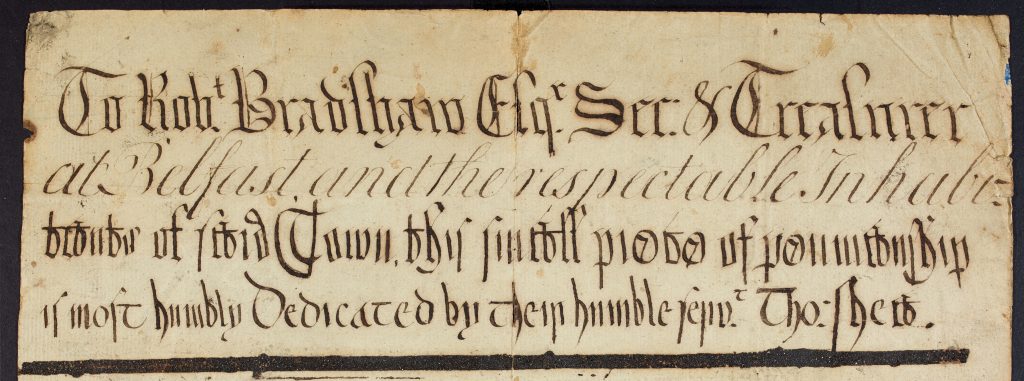

The handwritten section of the letter has three sections. At the top is the spectacular display calligraphy. In the middle is the show-off Irish translation of the Latin epigram. And down the left is the body of the letter explaining what is going on. We will deal with each part in turn.

The display calligraphy is in five different scripts. The first line is in gothic black-letter; the second line is in copperplate italics, and the third line is in a strange antique looking script, which I don’t quite recognise, but which I think is a kind of Gaelic script. The fourth line is a more normal Gaelic script, but two words “dedicated” and “Tho:” are in a rounder version of this script.

To Robt Bradshaw Esqr Sec. & Treasurer

NLI MS 4562, Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

at Belfast, and the respectable inhabi=

tants of said Town, this simple piece of penmanship

is most humbly dedicated by their humble servt Tho: Shea.

We can see that Shea is copying the titles or forms from the advert: “ROBERT BRADSHAW, Sec. and Treasurer, BELFAST” and “A respectable body of the Inhabitants of BELFAST”.

Where the printed text has “his _________”, Shea has overwritten “their Honours”

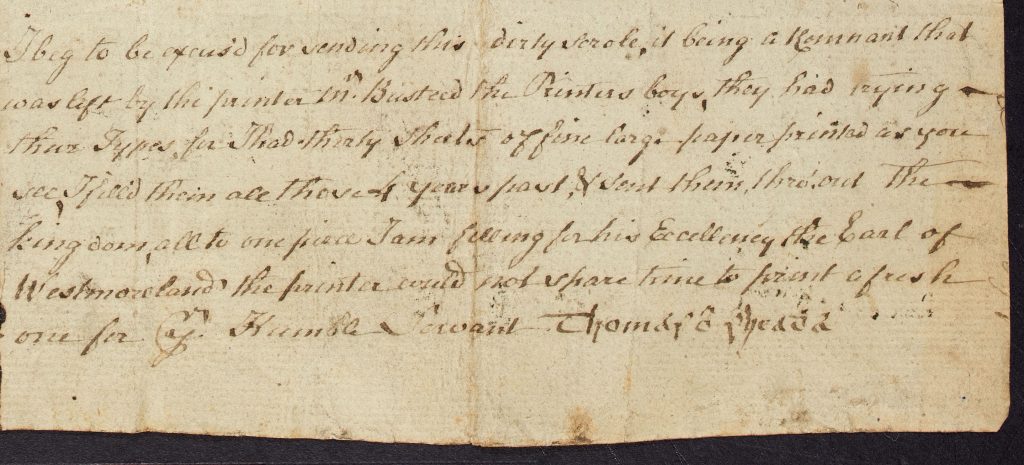

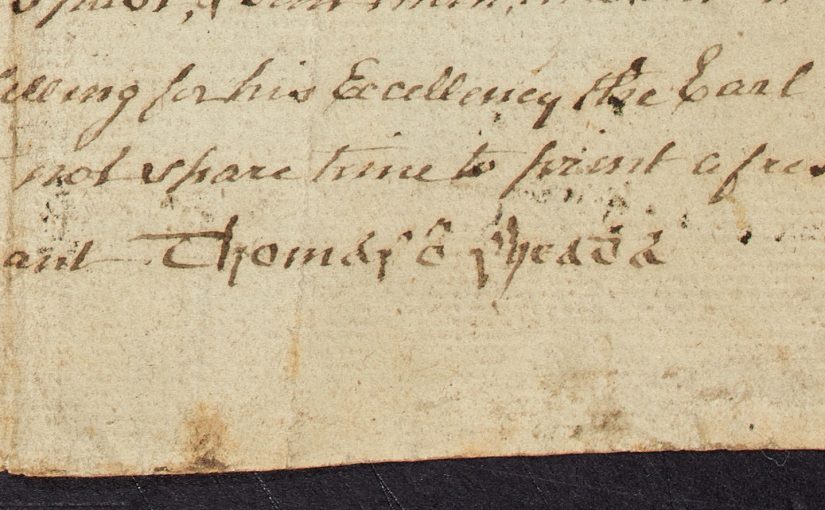

Down the left margin, in a cursive italic script, Shea writes an explanation about the printed sheet, which I have quoted from above.

I beg to be excus’d for sending this dirty scrole, it being a Remnant that

NLI MS 4562, Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

was left by the printer Mr Busteed the printers boys, they had trying –

their Types for I had thirty sheets of fine large paper printed as you

see, I fill’d them all these 4 years past, & sent them thro’out the

kingdom, all to one piece I am filling for his excellency the Earl of

Westmoreland the printer could not spare time to print a fresh

one for yr Humble Servant Thomas ó Sheaḋa

He writes his name here in Irish script, with the dot above the d (for “Ó Sheadha”). It is actually quite interesting that he does not give any more information about himself, what he thinks of the Belfast meeting, or why he can’t come; he is just framing his sending of his printed promotional material.

The 10th Earl of Westmorland was Viceroy at this time, so Shea was definitely aiming high with his letters.

Towards the bottom of the printed text, apropos of nothing really, it says

In praise of the old fam’d harp by Virgil 40 years before the birth of Christ:

NLI MS 4562, Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

Arbo[r] eram silvis donec percussa s[e]curi

viva nihil dixi Mortua læta cano

The above verse translated by said Thomas Shea.

And then a space has been left for Shea to show off his penmanship and his ability to translate from Latin into Irish. He has written, in a lovely Gaelic script:

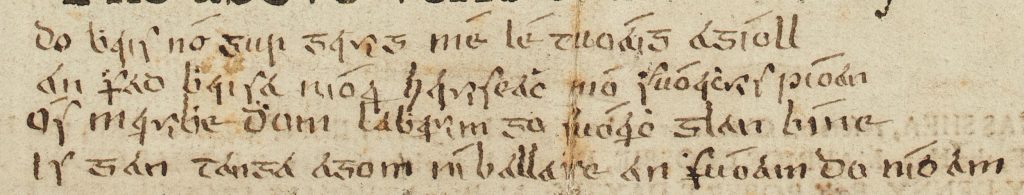

do bhais nó gur garuig mé lé tuoáig agíoll

NLI MS 4562, Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

an fhad bhaisa níoar haruiseach mó shuóarchuis píoan

Ós maruibhe dhom labharuim go suóarch glan bíne

is gan tanga agom ní ballaue an fhuóam do ní[dh]am

Some of the letter-strokes are very wiggly, so you can see that Shea had a bad shake in his hand as he was writing. The spelling is a bit wayward, and so Alf MacLochlainn suggested a normalised version in his article:

Do bhíos nó gur gearradh mé le tuagh i gcoill

Alf MacLochlainn, ‘Thomas O’Shea, a Kerry harper’, in Journal of the Kerry Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol.3, 1970, p82

An fhaid bhíos-sa níor thairbheach mo shuairceas poinn,

Ós marbh dhom labhraim go suairc glan binn,

Is gan teanga agam ní balbh an fhuaim do-ním.

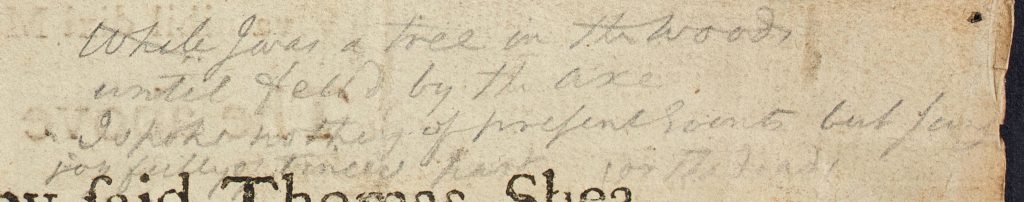

We can also check the (later) English translation that has been pencilled in beside the Latin. I would say this is a late 18th or early 19th century pencil script, perhaps written in by one of the Committee in Belfast:

While I was a tree in the woods

NLI MS 4562, Courtesy of the National Library of Ireland

until felld by the axe

I spoke nothing of [present ???ts] but [sing]

joyfully [of times past] or [the dead]

Unfortunately the pencil is very faint and I can’t make out the ends of the last two lines. It does not seem to be a literal translation of the Latin or of the Irish but I shouldn’t really say that if I can’t make out all of the pencil writing!

The Latin

Let us digress for a while and discuss this little Latin epigram.

Versions of this text seem to be fairly common as inscriptions on stringed instruments, basically stating “when I was alive in the woods I was silent, now I am dead I sing sweetly”, with more or less elaboration about axes or whatever. For example, a 1710 octave spinet in the Raymond Russell Collection in Edinburgh has the inscription “dum vixi tacui mortua dulce cano”. This instrument is the starting point for an investigation by E. K. Borthwick: ‘The Riddle of the Tortoise and the Lyre’, in Music & Letters Vol 51 No 4, Oct 1970 p373. Borthwick connects the text back to the Ancient Greek tradition of the lyre made from a tortoiseshell, (though Batman tells us that the first lyre was made from the shell of a snayle).

I am not finding any connection to Virgil, so I am not sure if Shea’s statement about this has any basis in truth.

I am aware of two other versions of this text in the context of Irish harps. One is from a Dublin newspaper, from before Shea wrote his letter

POETS CORNER

Hibernian Journal, Mon 19 Apr 1773 p4

………………………

To the CONDUCTORS of the HIBERNIAN JOURNAL.

GENTLEMEN,

THE following Distich was lately found in the belly of an old Irish Harp. I cannot recollect that I ever met with it before. But as the Thought is easy, natural, and elegant, I have no Doubt of your admitting it into your Paper if it be really new; although the Translation cannot, perhaps be so easily approved.

I am, Gentlemen,

Your most humble Servant.

Epigraphe sub Concave Citharæ Hibernicæ inventa.

In Sylvis vixi, donec percussa Securi:

Dum vixi, tacui; mortua dulce cano.

Translated.

I flourish’d long a Tree, the Forest’s Pride,

‘Till by devouring Axes fell’d, I dy’d:

Mute when alive; now now levell’d to the Ground,

I’m vocal grown, and charm with dulcet sound.

March 25, 1773.

The other is from a very tantalising report of a harp belonging to the Buchanan family in Jeffersonville, Indiana, USA. The description was originally published in 1896 and was subsequently reprinted in newspapers and books (thanks to Karen Loomis for tracking down the original publication of this report, after I showed her a newspaper reprint). The article says that Buchanan family came from Scotland to County Tyrone in 1640, and then moved to America “about forty years ago” (i.e. in the 1850s), bringing the old harp with them. The article says

There was then visible on the sound-box a plate, now covered by one of the iron bands, on which plate was inscribed –

The Sketch, vol XV no.182, Wed 9 Sep 1896 p270

In sylvis vixi donec percussa securi

Viva nihil dixi, mortua leta cano

Cormack Kelly me fecit, Anno Domini 1617

The harp is also described in enough detail that we can be sure it is real, but not quite enough to really understand it. I think the date must be wrong, and probably should read 1717 or perhaps 1716. Apart from this being a fourth example of the work of Cormick O Kelly (we have the Downhill harp, the Otway harp, the lost Magennis harp, and now this lost Jeffersonville harp), the inscription is very interesting. This seems to be slightly different from the text published in the Hibernian Journal, and so I would not like to say that the Hibernian Journal contributor got the inscription from the Jeffersonville harp when it was in County Tyrone, although it is possible he did, and then garbled it.

I think that Thomas Shea’s version of the Latin text is also different enough that it is not copied either from the Jeffersonville harp or from the one that the Hibernian Journal contributor saw.

I don’t think this verse has anything to do with Virgil.

Did Thomas Shea’s harp have his Latin text on it as an inscription? If not, where did he get it from?

Thomas Shea’s harp

Thomas Shea tells us in the printed text of c.1788 that “there is not one Harp kept in order in this County, but what said Thomas Shea has”.

Thomas Shea’s harp would have been a full-sized wire-strung Irish harp, probably made in the early 18th century.

We do have one 18th century style Irish harp with a County Kerry provenance, the Mulagh Mast harp. Now it is probably not Thomas Shea’s harp, since he says that when he started to learn in 1717 there were “upwards of one hundred harps” in County Kerry, and so even if the Mulagh Mast harp was in County Kerry for its whole working life there is less than a 1% chance that it was actually Shea’s.

On my old website just before I closed and archived it, I wrote a page about the name of the Mulagh Mast harp, and the various possibilities of where it came from. One of the possibilities is Mullaghmarky House which is near Tralee.

Anyway this gives us some sense of what kind of a harp Thomas Shea likely had.

Thanks to the National Library of Ireland for giving permission to reproduce Thomas Shea’s letter.

Fascinating…..really interesting about the inscriptions.

Here’s a different version of the Latin, inserted out of context in the middle of a review of Edward Bunting’s Ancient Music of Ireland: