I don’t know of any historical information about Cormac Ó Ceallaigh the harpmaker. Perhaps that’s not surprising for a Catholic at the times of the penal laws, living and working in a wooded valley up in the mountains, and working in an old oral tradition.

But there is a fair amount of traditionary information referring to him. By its nature this information may be wrong, but I thought I could try lining up what I have found so far, to collate all the different information, look for patterns, and maybe get ideas for future research or clues for other places to look.

Seán Donnelly wrote a section of an article about Cormac’s life and works (Seán Donnelly, ‘An Eighteenth Century Harp Medley’, in Ceol na hÉireann vol 1 issue 1, 1993, p.14-16). Michael Billinge has been collating information about Cormac’s harpmaking activities, and I have referred to some of their references, but I am also looking for information about Cormac’s wider social and historical context as well.

Cormac Ó Ceallaigh is known as a harpmaker, and his name is inscribed on two extant old Irish harps plus one lost instrument. The extant harps are the Downhill harp in the Guinness Storehouse Museum in Dublin, and the Castle Otway harp in Trinity College Dublin. The lost example is the Magenis harp, known from a 19th century description and painting.

The name is spelt differently on the inscriptions. The Downhill harp has the famous poem inscribed on the soundbox, and the makers name is written “CR KELY” with the date “17 HVNDRED AND 02”. The Otway harp has its inscription running down the inside of the forepillar, and the name is written “CORMICKOKELLY” and the date “1707”. The Magenis harp soundbox inscription reportedly has the name “CORMICK O / KELLY” broken over two lines, and the date “1711”.

We cannot assume that these inscriptions were all genuinely put there by Cormac when he made each harp; they may have been added later to give a false provenance to an older or younger instrument. All three give an English form of the name; the poem on the Downhill harp which contains the name and date is all in English. The Magenis inscription is in English and Latin. Diarmaid Ó Catháin has pointed out that this is perhaps surprising, and that we might expect Cormac Ó Kelly to have used Irish. Does this tell us something about the customers who ordered or commissioned these harps? Was English even in this context seen as more high-status and more suitable for a display inscription by 1700? Or is it an indication that the inscriptions are all later spurious additions?

The earliest securely dated reference to Cormac I have found so far is in the description of Denis O’Hampsey written by Rev. Sampson and published in 1806 in The Wild Irish Girl. Sampson includes a description of the Downhill harp, and as Mike Billinge points out, mis-quotes the harpmaker’s name “Cormac Kelly”, suggesting that the name came from tradition rather than from reading the inscription.

Places

In a footnote on p.24 of the introduction to Edward Bunting’s 1809 Collection, is the following information, which is assumed to refer to the Castle Otway harp:

A Harp made by Cormac O’Kelly, of Ballynascreen, in the county of Londonderry, about the year 1700…

I think this is the earliest information connecting Cormac to Ballinascreen. In his 1840 book, Edward Bunting mentions Ballinascreen as “a district long famous for the construction of such instruments, and for the preservation of ancient Irish melodies in their original purity” (p.77). However, Bunting may be over-egging things here, since he also says that the harp, illustrated by Walker (1786) and said by Walker (p.163) to be inscribed “Made by John Kelly 1726”, was “made by Kelly, of Ballynascreen in 1726” (p.77). Was Bunting reporting genuine traditionary information or was he conflating disparate sources to fabricate a good story?

The Irish name of this parish, Baile na Scríne, comes from the old church of Scrine. The place is called Scrine (library) because it is supposed to have been founded as a library by St Patrick. There are many traditions connected to the church, including its bell which is said to be X.KB 2 in the National Museum of Scotland.

This interactive map shows the parish of Ballinascreen, and the half-townland of Creeve. Open in new window

The Ordanance Survey letters of John O’Donovan contain information about the O’Kelly family, although I don’t find any reference to Cormac. The O’Kellys were said to have been hereditary seanchaithe historians of Gleann Con Cadhain, and had collections of manuscripts. (letter 14D 21/29, 11 September 1834. PDF facsimile, PDF p.314). Gleann Con Cadhain comprises Ballinascreen plus the two parishes to the East.

O’Donovan also gives other useful local information, including that the valley was formerly heavily wooded down to the 18th century (PDF p313)., but that the woods were cut down for charcoal-burning for local iron mills and blacksmiths and also for export (PDF p329)

We get more specific information about where Cormac lived from Énri Ó Muirgheasa (Henry Morris), Dhá Chéad de Cheoltaibh Uladh (1934). Seán Donnelly’s 1993 article reproduces and translates the relevant passage, which describes the half-towland of An Chraobh (Crieve or Creeve), being the northern half of the townland of Doon. Ó Muirgheasa implies (though he does not state explicitly) that Cormac Ó Ceallaigh lived in An Chraobh.

Ó Muirgheasa refers to him as “Cormac na gCláirseach” (Cormac of the harp) and says his son was called “Maghnus na gCláirseach” (Magnus of the harp). Seán Donnelly assumes that Magnus was also a harp maker, but we are not told this. Cathal O’Shannon was more explicit in The Evening Press, (Friday May 1, 1964, p.12): “The famous harpmaker was a native of the townland of An Chraoibh, or Creeve, which I knew very well…” O’Shannon gives a lot of useful information about other members of the O’Kelly family of the area, from his own personal knowledge.

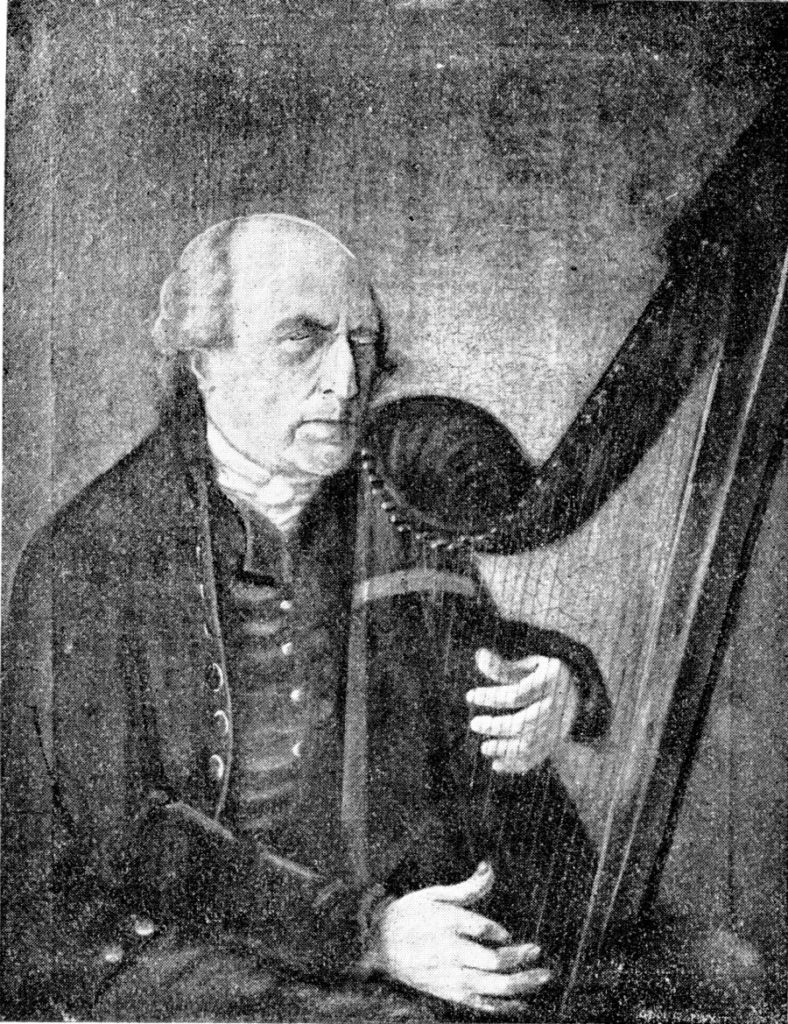

Portrait

There is a portrait that is said to be of Cormac Ó Ceallaigh. It was printed with a brief commentary by Breandán Breathnach, in Ceol vol 1 issue 3, Winter 1963, p.11–12. The item was headed “Cormac O Ceallaigh” and consists of a brief note about Cormac, lifted from Bunting’s 1840 book, mentioning Ballinascreen, and mentioning the Downhill harp. The article also comments on the Downhill harp having “acquired recently” by Guinness, and says the harp “is at present on exhibition in the USA advertising that firm’s Harp Lager”.

Breathnach concludes, “the portrait above, a reproduction from another print, was kindly made available by Colm O Lochlainn, Three Candles Press, Dublin. Unfortunately, it was not possible before going to press to ascertain from Colm who the artist was”.

There is an undated letter from Breandán Breathnach in the NMI Archive (file AI 64 006) which says “C Ó Lochlainn, the Three Candles, gave me a block of the harper for use in Ceól. I have a few notes collected on Ó Ceallaigh but should like to say who painted the original and where it is now.” A b/w photo of the painting is with the letter, with the name “Cormac Ó Ceallaigh” hand-written on the photograph. There is also a draft reply from William O Sullivan who says (tentative reading!) “I am retaining the print of the harper with the hope that [illegible]. The name of the painter is not legible and the print is a half tone made from another print not from the original painting. The national library research also failed to yield anything”

The painting is now in the National Gallery in Dublin, ref. NGI.1200. The catalogue says it was purchased privately in 1951. The catalogue also says it is of Arthur O’Neill, and says it was painted by Conn O’Donnell. A black-and-white reproduction was printed in Early Music May 1987 (frontis) where it was captioned as Arthur O’Neill (presumably following the NGI attribution); this reproduction allows the artist’s signature to be read as “ODONEL PINXIT”

I don’t know where either of these claims come from. I don’t think it looks much like the other portraits of Arthur O’Neill; but I have no idea why Colm O’Lochlann might have thought it was Cormac Ó Ceallaigh. Did Ó Lochlainn have traditionary information about the painting? More curiously, I have never come across “another print” which this reproduction is supposedly copied from. The letter refers to a “block” – did Ó Lochlainn give Breathnach a printed paper copy of the picture, to be photographically reproduced, or did he actually give Breathnach a wood-and-metal halftone printer’s block for Breathnach to use directly in printing the copies of Ceol? How does the copy on photographic paper preserved in the NMI archive relate to these? Ó Lochlainn was a publisher, setting up his own publishing house, “at the sign of the three candles”. Did he intend to publish the portrait in one of his own books? Most curiously, the painting was already in the National Gallery at the time of this correspondence and article, though Breathnach didn’t know this. In the letter, Breathnach explains “CÓL is sick so I can’t ask him”.

The harp is shown with the strings on the wrong side of the neck.

Further research

I need to go to An Chraobh to see his places. And we need to keep an eye out for other traditionary or historical references to Cormac.

Thanks to the Irish Traditional Music Archive for supplying this scan from Ceol and giving permission to reproduce it a few years ago. I should also thank Ann and Charlie Heymann for sending me the Cathal O’Shannon newspaper cutting, and Seán Donnelly for sending me a copy of his article.

Colm Ó Lochlainn published more info two years later, in his book More Irish Street Ballads (Dublin: The Three Candles, 1965).

On p.204, in the notes to the song no.8 “The verdant braes of Skreen”, he writes “More than fifty years ago I learned this from Dr. Séamus Ó Ceallaigh who lived at 53 Rathgar Road. He was a native of Ballinascreen and numbered among his ancestors Cormac Ó Ceallaigh, a famous harper and harp-maker. See Ceól No. 3. … In Dr. Ó Ceallaigh’s house was held one of the last meetings of the leaders before the Rising of 1916.”

And in the notes on tune no. 9, “Sliav Gallion Braes” he writes “This also from Dr. Ó Ceallallaigh…”

The bell is listed as no.43 in Cormac Bourke’s book, The Early Medieval hand-bells of Ireland and Britain (Wordwell/NMI, 2020). The commentary is on p.348-9 and photographs are on p. 552-3. The bell is said to have been named Dia Díoltas (vengeance of god)

Adrian LeHarivel at the National Gallery kindly checked the NGI archives for me. He tells me that the portrait was purchased by the NGI in 1951 from a Dr O’Kelly. This Dr O’Kelly provided a letter with the painting, giving its provenance, saying that he had purchased it from Jack O’Donnell, a descendant of the artist at Larkfield, County Leitrim. O’Kelly says that the painting had always been at Larkfield, and that the O’Donnells at Larkfield had maintained that it was of Arthur O’Neil. Kelly also says he was shown Conn O’Donnell’s studio room. So this gives us a much more secure connection of the painting to Arthur O’Neil.

LeHarivel also pointed out to me that Arthur O’Neil tells us he visited Conn O’Donnell at Larkfield: “…I next came into the County of Leitrim and came a Cornelius ODonnells of Larkfield where I again met my Dear Hu: ONeill who was then there on a visit…” (QUB SC MS4.46 page 36). This seems to be connected to the return from Granard in 1782.

I don’t know at this stage if the Dr O’Kelly who owned the painting and provided the information to the NGI is the same person as the Dr O’Kelly who gave Colm O’Lochlainn the songs and who claimed descent from from the Ballinascreen O’Kellys.

I viewed the painting at the National Gallery. It is life-sized, and in person it looks a lot more plausible as a likeness of Arthur O’Neil. As well as the signature of the artist there is a much fainter date, only recently revealed by cleaning: “C.O.DONEL.PINXIT.1804”. The paint has flaked off over a lot of the painting, including almost all of the neck of the harp, but despite this the painting is very informative as well as inspiring. The soundboard has indications of triangular string shoes.