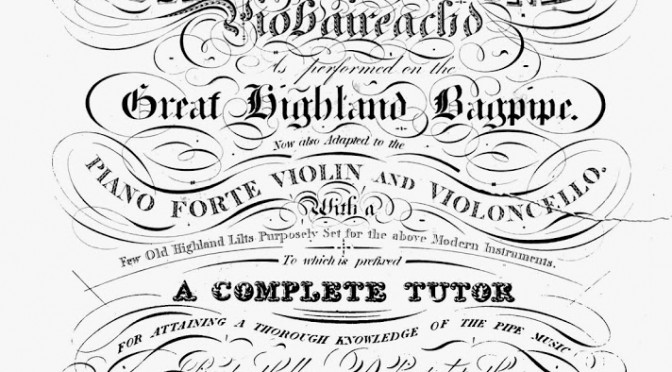

I am intrigued by Donald MacDonald’s arrangements of ceòl mór or pibroch, because on his title page he indicates that he is not setting out the tunes in “pipers tablature”, that cryptic system that looks confusingly similar to staff notation; instead, he describes his work:

A / collection / of the / Ancient Martial / Music of Caledonia / called / Piobaireachd / as performed on the / Great Highland Bagpipe / Now also adapted to the / Piano Forte, violin and violoncello…

By setting the music on two staves, treble and bass, he intends that the purchasers of his book, price one guinea (£1 1s, or a few hundred pounds in today’s money) to play this music not on the pipes (what wealthy, musically literate book-buyer in 1820 owned or played pipes?) but on the piano; if they had musical guests at their Edinburgh townhouse they may well also try it as violin and cello duets.

Donald writes a single bass line very simply in the bass clef, which looks to me quite old-fashioned for 1820; I think by that date many music arrangers were writing chordal and thicker textures in the bass. On the other hand the modal, drone-based nature of the music may have discouraged anything more complex.

He writes the melody in a more nuanced way, setting the tune in large notes with their stems all pointing down, and using little notes with the stems up to indicate the characteristic bagpipe grace-notes. I imagine he expected piano and fiddle players to ignore these in performance, but to appreciate them as exotic talking-points read in connection with the “instructions” at the beginning of the book.

How did he decide which notes to make big, and which small? This is the vexed question of all early pibroch scholarship, since there seems to have been a strong movement through the 19th and 20th century to shift the musical emphasis in a big way, with melody notes becoming swallowed up into bundles of gracenotes, and rogue grace notes being held so long that they speak as stressed melody notes.

My opinion is that he wrote the big notes so that when played normally on the fiddle or piano, the melody sounded as he imagined in his head that it should, based on his knowledge of the expected traditional expression of this tune on the pipes (and perhaps also on the fiddle, seeing as the fiddle pibroch tradition may have still been reasonably strong at this time)

Hi Simon,

You have a great site! I was researching the tune “The Amorous Lover” (C’uin a thig thu ars am Bodach) found in Donald MacDonald’s Collection for an authentic bagpipe setting. Is there a date on the book at all?

The National Library of Scotland cites the date as 1822. Yet, I could not find such a date on the book photocopy (from the Glen Collection). However, you document an 1820 date in your research article here (and so too says the National Museum of Scotland). Can you please confirm this for me?

And a curious aside, on page 2, D. MacDonald tells pipers to disregard any sharps or flats in the signature as these are essentially not playable. But on page 6, he confounds the piper and writes in G-sharps into the “Amorous” tune, which can be only for the piano and fiddle, just as you point out. This causes me to doubt that his transcription of the “Amorous” tune is an authentic bagpipe setting!

Cheers!

Shawn Cassady

Dating the book: I would always check Roderick Cannon’s bibliography (updated by Geoff Hore). Unfortunately it is now offline but you can get an archived version. They seems to suggest that there were many reprints and re-editions. They reference a full analysis of the publication history in Roderick Cannon and Keith Sanger, Donald MacDonald’s Collection of Piobaireachd Volume I (1820) volume I (The Piobaireachd Society 2006) and volume II, (The Piobaireachd Society 2011).

To find “an authentic bagpipe setting” you really need to find a piper who has learned it in the inherited tradition. Donald MacDonald’s settings are “authentic” in that he was a piper and was writing down the tune as he had it from the inherited tradition; but it is not “authentic” in that he has arranged it for piano, so as to be able to publish it for a literate classical audience.

I find the key signatures in Donald MacDonald’s piano arrangements fascinating, since they are obviously not relevant to pipers, who as you say always play C♯ and F♯ whatever is written in the key signature. But to play Donald MacDonald’s arrangements on the piano is a fascinating exercise, and then I think his various key signatures tell us something about how the key or mode of each tune might have been perceived by a traditional “insider” – in terms of the different modes and roots from within the Gaelic music system (which is very different from classical keys). Or alternatively you could argue that Donald MacDonald was using the key signatures to de-traditionalise his settings for the piano, by forcing them into classical keys. I do not know which is correct.