After I finished working on the tune and story of Eleanor Plunkett, I picked up on a reference from Alasdair Codona’s writings. Alasdair had pointed out that tune no.94 titled “Kitty Magennis” in Donal O’Sullivan’ Carolan the Life Times and Music of an Irish Harper (1958) was actually another version of the tune of Eleanor Plunkett. I added a comment to my Eleanor Plunkett blog post to include a facsimile of O’Sullivan’s source and a typeset and mp3 version.

Continue reading A previously unpublished Carolan tune: Kitty MagennisCategory: research

Irish Harpers particularly from Belfast

File AI.80.019 in the NMI archive contains papers associated with a harp (NMI DF:1980.6) which is said to have originally belonged to Valentine Rainey, master of the Belfast Harp Society school in the early 19th century. The file includes letters relating to the purchase of the harp, as well as photocopies of a selection of other documents which may have come with the harp; there are some pages from Charlotte Milligan Fox’s book, Annals of the Irish harpers (1911), a photo of the harp with some information about its provenance, and a couple of handwritten pages of information about harpers.

There is no other information about these handwritten pages; all we have is the photocopies themselves. One is obviously a quick draft version, and the second a neater and slightly fuller version. The handwriting is difficult to read. This is my transcription of the two sheets.

Continue reading Irish Harpers particularly from BelfastThe incredible shrinking harp

When my replica of the Queen Mary harp was new, Keith Sanger suggested to me that I should measure it repeatedly over time, to see if and how much it changed shape and size over the years.

The idea is to get some idea of how reliable the measurements we take of the old harps in the museums are, and how much the old harps might have changed shape from when they were new to how we see them now.

Continue reading The incredible shrinking harpRobin Adair

Last week I was working with Karen Loomis, for the Historical Harp Society of Ireland, in the National Museum of Ireland, studying the Hollybrook harp (NMI DF:1986.2). The harp was purchased by the Museum at Sotheby’s in 1986. The auction catalogues and museum archives do not have any more information about the provenance before it was sent to auction.

The Hollybrook harp was described and illustrated by Robert Bruce Armstrong in 1904. He says it belonged to Robin Adair at Hollybrook. I am trying to unpick the rather confused information about these people and places. I am sure there is a lot more fine detail to uncover about the life of Robin Adair and the places he lived and visited, and his friends and associates, but this will do for a start.

Continue reading Robin AdairOld Irish harp transcriptions project

I first got hold of a facsimile of Bunting ms29 (Queens University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4/29) when it was first published online at QUB Library web site, back in 2006, and I have been working from the facsimile ever since.

Continue reading Old Irish harp transcriptions projectThe Best harp

The Best harp is probably the worst of the surviving old Irish harps. It has been almost completely ignored in the literature. Joan Rimmer does not mention it; R.B. Armstrong does mention it but he failed to understand what it was, and he mis-identified it.

The Best harp was given to the Royal Irish Academy by the Rev. Berkeley Baxter, in 1882. The Wakeman catalogue of the RIA lists the harp as No. 369, and says that the harp was transferred to the Arts & Industry division of the National Museum of Ireland on 19th July 1958, under the reg. no. 93-1946. The harp is now at the National Museum with the accession number NMI DF:1946-93.

In the Freemans Journal of December 1882 there is an account of the provenance of the harp:

All that is known of it is, that a very old minstrel, some generations back, was frequently the guest of a clergyman of the name of Best, in the county Sligo, and that at his death the venerable minstrel bequeathed his harp to his worthy host, stating that it was an heirloom which had descended to him from his ancestors. Mr. Barter acquired the harp in 1879… from a lady, the descendent of the Rev. Mr. Best, and who is herself a distinguished harper.

Who was Rev. Best? At Michael Billinge’s index of old harps, it is suggested that he was the Rev. Best of Tandragee, County Armagh, mentioned by Andrew Craig in 1787, but this seems unlikely, since we know our Rev. Best was in County Sligo. I have not yet been able to find any more information about “Rev. Mr. Best of Sligo”. We might suppose that Rev. Best was dead by 1879 at the latest, so that his daughter, perhaps, had inherited the harp. Or he could have died decades before, and passed the harp down for many generations. So the “venerable minstrel” could have died any time before 1879. Not very helpful…

The account does, however, suggest that the harp may have been a genuine working instrument of a harper in the old tradition, and so I considered that it was worth studying, even though it is the worst of the old harps and is basically a horrible thing.

Neck

The frame of the Best harp is pretty horrible. The neck is perhaps the nicest part, carved fairly competently from a piece of very dark wood (the Freemans Journal says “ebony”, though I doubt this. Wakeman says it is “stained black” which I also doubt). But even then, there are two things about it that set it apart from the mainstream of old Irish harp norms. One is that it does not have the metal cheek-bands, which the tuning pins pass through; they seem never to have been a part of this harp. The other is that the curve of the tuning pins turns down in the treble, making the treble string lengths very badly scaled.

The bass end of the neck fits, as is usual, into the back of the forepillar. But the treble end of the neck, very unusually, fits into the front face of the soundbox. The only other old Irish harp I know of that does this is the Malahide / Kearney 2 harp, whose current location is unknown.

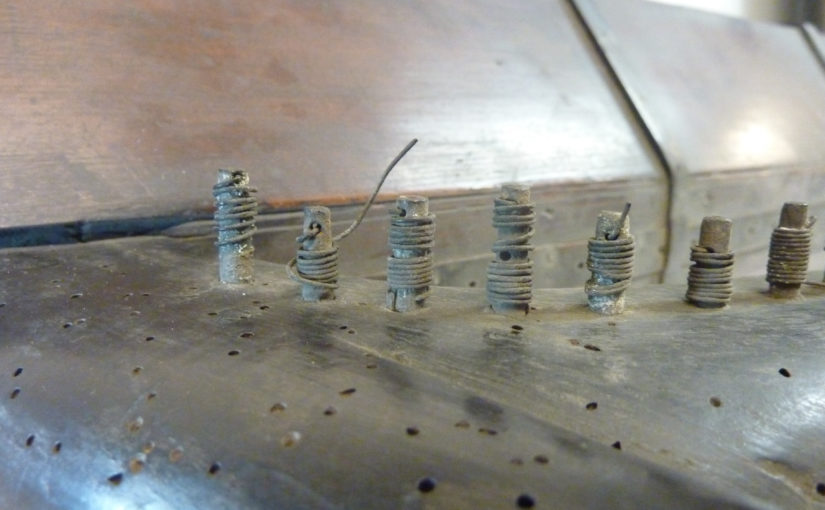

The neck has 35 tuning pins in it, Nos. 2, 4, 5, 9, 11, 12 and 34 are iron, and all the others are brass. Every pin except no.13 has the end of its string wound around it, though the free sounding part of each string has been removed. The pins are plain and undecorated and are not all identical, though they are nicely made of type 1a or 1b.

Soundbox

The soundbox of the Best harp is pretty crude, compared to the elegantly shaped and hollowed one-piece soundboxes of the other old Irish harps. Wakeman says it is “red sally” (i.e. willow). The soundbox of the Best harp is assembled from eight separate pieces of wood, having a five-sided cross-section. This is the same construction seen in the Malahide / Kearney 1 harp, where the front is formed from three planks, having a flat front and angled flanks. The soundbox of the Best harp is parallel in depth all the way along, though it appears to taper a little in width.

There are two sets of brass fittings on the Best harp soundbox. There are thin brass strips on the front: a long strip runs down the centre-line and has 36 string holes which line up with the holes in the wood. There are also three lateral strips which wrap across the front and are fixed onto the sides. The other fitting is the heavier brass plate with engraved lines at the top of the back of the soundbox.

There is an inscription on the bass end of the back, which seems to read IWI.

There is no projecting foot on the soundbox; this is unusual on the old harps, with only the Clonalis Carolan harp similarly lacking a foot. The lower rear edge of the Best harp’s soundbox is very worn away, as if it had been played resting on that edge a lot.

Inside the soundbox, there are the ends of some of the strings. There are 10 strings and toggles still there. 8 of them are just the stubs, jammed into the string holes. Two are longer lengths, attached to the stringholes but with their toggles dangling inside the soundbox.

There are three different kinds of toggles. Strings 17, 19, 26 and 31 have wooden toggles. Strings 6 and 18 have iron screws attached as toggles. And strings 1, 2, 3 and 5 are toggled onto what look like toggle-knots that have broken from their strings and removed from their toggles.

Forepillar

The forepillar is the worst part of the Best harp. It looks like a broom handle painted black. It is straight, slender, and cylindrical all the way down, except for the ends where it squares off. It does not look strong enough to resist string tension, and it is so straight and slender that it looks ridiculous compared to the rest of the harp (even though the neck and pillar are hardly objects of great beauty and elegance). I wonder if it is a replacement for one that was broken or damaged.

Strings

The Freemans Journal article says that the harp “has 35 strings made of brass wire”; Wakeman says that “portions of wire strings remaining”. Now, the harp is basically unstrung, but the strings have been cut from the harp, leaving the coils wound around the tuning pins, and leaving some toggled ends inside the soundboard. Was this done after the Freemans Journal article? Or did the article interpolate from the fragments?

Were these string fragments the remnants of the last working stringing and setup of the harp? I think it is likely that all of the other old harps in the Museum that have strings on, have been restrung for display purposes since the harps became non-working collectables. So if we had a harp retaining its old stringing that would be very valuable.

I went to the Museum and I measured as much as I could manage by hand of the old strings. I think a lot more data could be extracted from this harp by using more high-tech methods, but this will do for a start.

All but one of the pins retains a winding of brass wire on it. Two of the pins have two windings, no. 18 perhaps being merely a single coil that has broken, but no.28 being very clearly a thinner coil that was a complete string, and a thicker bit of wire looped around the pin beneath it. All of the wires were wound clockwise around the pin end, to drop the string from the back of the pin. All of the windings were neat and close, not crossing, with the end inserted neatly into the drilled hole .

There were a few strings out of sequence, but the majority of the strings seem to be in the right place, and to increase from 0.7mm in the treble to 1.1mm in the bass.

I would summarise these measurements as saying the harp seems to be intended to have 0.75mm brass wire for the top 5 strings, 0.7mm for strings 6 to 16, about 0.9mm for 17 to 29, and 1.2mm for 30 to 35, with a few strings being the “wrong” size.

I also measured the string lengths. Because there are 35 tuning pins but 36 string holes, there are two possible configurations, 1-1 and 1-2. I measured both, but I think 1-1 is much more plausible. It is possible there was originally a 36th pin mounted on the forepillar, supposing the current stick is not original. The string lengths are a bit odd, with a few far-too-long strings in the treble (where the line of pins on the neck bends up then down), and with the mid-range and bass a lot shorter than an ideal (pythagorean) scaling.

This combination of having string lengths, and having wire gauges, allows us to plot a possible tuning regime for this harp. Unfortunately, the current stringing and setup of the Best harp seems to be as horrible as its design and construction. The use of 0.7mm brass wire in the treble means the treble strings are far too thick and far too high tension; the bizarre scaling of the harp means that the mid-range and bass strings are far too short and tubby.

The harp would speak with its lowest note at G (2 octaves below na comhluighe) and its highest note as e”’ one note higher than the top of the Downhill harp, at a slightly lower pitch than modern (perhaps a’=415). It wouldn’t go higher than that without snapping strings 4 and 5. At this tuning the total tension on the harp would be around 475kg which seems rather high for the slender neck and ridiculously slender forepillar.

Here are all my measurements, with estimated accuracy, and a calculated stringing chart: Rev Best string measurements pdf

If I were stringing and tuning a replica of this harp I think I would disregard the top five strings. Because of their bizarre toggles, I think they could be considered later cosmetic additions. Perhaps those top five should be thinner (the thinnest wire on the harp is no. 20, obviously out of place, measuring about 0.55mm). These top five could even be iron allowing a slightly higher pitch standard for the harp. And strings 5-6 is a good place to change gauge, being g-a on my suggested tuning.

So how do we regard the Best harp? Was it really strung and played in its current state by the “venerable minstrel” who visited the Rev. Mr. Best at his house in Sligo? If so, did this old harper know that he had the worst harp in Ireland?

How are we to assess the quality of an old harp? We are not in the tradition, we do not know what aspects of a harp are more or less important. It is easy to take a modern attitude, and to expect certain types of sound, touch, aesthetic and engineering criteria when we look at a harp. Perhaps the old harper who set up and played the Best harp thought it was fine, perhaps he was able to play it well to good effect. Perhaps he used the over-heavy treble and twangly bass for a specific traditional style of harp playing.

Or, was the harp a failed experiment by an incompetent harper trying to get a harp on the cheap from a local carpenter? Were the strings put on it after the harper died and bequeathed it, just using whatever wire was left over in his string-bag, to try and make it look presentable for display in the entrance hall of the Best residence? What did Rev. Best’s descendent, the “distinguished harper”, who passed it on to Berkley Baxter, think of it? Did she try to play it? Was she glad to get rid of it?

There is a story behind every artefact, a sequence of human interactions that layer upon layer shape and affect the material object. Every aspect of the Best harp has been done by Human agency. Someone has wound those strings on, someone has snipped them off. Someone has wound string 28 with a fat bit of wire jangling round the tuning pin shaft. Someone has wound the toggles and the wood screws and the strange loops in the treble. Who? Why? What were they even thinking? We cannot know, but we can analyse the stuff they left behind to try and work some of it out.

Thanks to Sarah Nolan and to the National Museum of Ireland for facilitating my visit.

Carolan’s original harp bass

Carolan’s tunes had no base to them originally, as we have been informed by the late Keane Fitzgerald, a native of Ireland, and a good judge of music, who had often seen and heard old Carolan perform. It was only after his decease, in 1738, that his tunes were collected and set for the harpsichord, violin, and German flute, with a base, Dublin, folio, by his son, who published them in London by subscription, in 1747.

Abraham Rees, The Cyclopaedia; or, universal dictionary of arts, sciences and literature. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown, 1819. Volume 17, (unpaginated, under ‘Harp’)

Charles Byrne

Charles Byrne is listed as one of the harpers who went to Belfast for the harpers’ meeting in July 1792. The collector, Edward Bunting, says:

Continue reading Charles ByrneA typology of tuning pins

There are a number of different styles of taper harp tuning pins. I am trying to categorise them so that it is easier to be specific when talking about the different types. Up to now I have talked about the “old” style with fat drive heads, and the “modern machine-made” style with narrow heads. But I see now that these are rough categories, which can be broken down more subtly.

I think the most distinctive and diagnostic thing is the relationship between the drive and the shaft. The drive is the square- or rectangular-section end of the pin, which is where you put the tuning key on, to turn the pin. The shaft is the conical main part of the pin, which is embedded in the wood of the neck, and also which carries the string at the far end. The shaft is always, and the drive usually, tapered rather than parallel-sided.

Basically I think the first diagnostic is whether the head is wider or narrower than the shaft; in other words whether there is a step up or a step down to the head from the shaft.

I’d suggest Type 1 pins have a step up from the shaft to the head; Type 2 pins have the head about the same size as the shaft, and Type 3 pins have a step down from the shaft to the head.

We could have sub-categories; sub-type a could have a sharp step at about 90°; sub-type b could have a clear transition at about 45°; and sub-type c could have a very smooth flat transition. We could also append R for pins with rectangular (not square) drives.

Because both head and shaft taper away from the centre of the pin, and because there is often a gradual transition from shaft to head, it can be hard to state at what point the diameter or width of each part should be measured and compared. So while it is easy to think about comparing the width of the head with the width of the shaft, it is often difficult in practice to choose where to measure. So my idea of looking for the nature of the “step” between shaft and head might prove more useful.

Type 3a (modern #5×3″ steel pin)

Type 3a (modern #4×3″ steel pin)

Type 3b (steel pin from Arnold Dolmetsch harp no.10, c.1932)

Type 2c (iron pin made by Simon Chadwick for a replica medieval Gothic harp, 2018)

Type 2cR (iron pin made by Simon Chadwick for the replica Queen Mary harp, 2014)

Type 2cR (brass pin made by Simon Chadwick for the replica Queen Mary harp, 2007)

Type 1b (brass pin made by Simon Chadwick for the replica Carolan harp, 2019)

Type 1c (brass pin from county Monaghan, c.17th century)

I think that previous attempts to document tuning pins have not been specific enough about where the measurements have been taken. The scheme below suggests where to measure:

B is the smallest diameter of the conical shaft of the pin

C is the largest diameter of the conical shaft of the pin

D is the largest width across the flats of the drive

E is the smallest width across the flats of the drive

F is the extreme end of the pin.

The following measurements can be taken to record a pin:

1. Distance A-B

2. Diameter at B

3. Distance A-C

4. Diameter at C

5. Distance A-D

6. Width across flats at D

7. Depth across flats at D

8. Distance A-E

9. Width across flats at E

10. Depth across flats at E

11. Distance A-F

From these measurements we can calculate the taper of the shaft, the range of sizes of tuning key socket which will fit the head, and the nearest standard taper hole that the pin will fit in. We can also work out the nearest standard taper blank to use for making a copy.

Irish libraries

I’ve been working in a lot of libraries recently. I love seeing inside different library buildings – the ambience and atmosphere and architecture sometimes seem as important as the collections.

Armagh Public Library was set up by an act of parliament which stated that it would always be called the Public Library, but they changed its name recently and it is now called the Robinson library after its founder, Archbishop Robinson. It is a handsome 18th century classical building stuffed full of handsome 18th century leather-bound volumes. This is the most elegant and beautiful library but is the hardest to make practical use of because its collections are so old-fashioned! I did check out their copy of the Memoirs of the Marquis of Clanricarde, to understand more the preface which famously mentions the performance of bardic poetry with harp accompaniment.

I had previously seen a copy of this book at Luggala. I remember somewhere reading an opinion that Garech Browne’s was the finest private library in Ireland, but I never managed to get to see inside – there was always some excuse, or distraction.

In contrast, the Irish and Local Studies library in Armagh is hidden round the back of a council building, entered through a basement door at the back of a car park. It has excellent collections of journals and newspapers – I never even got to go into the rooms with books! I found some very interesting references in very obscure 19th century periodicals here.

The other interesting library in Armagh is the Cardinal Tomás Ó Fiaich Memorial Library and Archive. I have not done proper research here, only browsed, but it has interesting local studies collections.

In Dublin I have been working at the National Library of Ireland, and also at the Royal Irish Academy. Both have beautiful buildings, and excellent collections; I have mostly been looking at specific unique items there. I have especially been reading the RIA minute books from the 19th century – I have not found what I am looking for in them, but that in itself is kind of interesting. They are really fascinating objects, full of the signatures of the Great Men like Petrie and Wilde. I have more references to follow up especially at the NLI, but it is harder to do because they are not so easy to get to.

In Belfast I have been using the Linen Hall Library and the McClay Library at Queens University Belfast. The Linen Hall library is a lovely old building full of lovely old collections, while the McClay is a really impressive new building with a tower that reminds me a little of Cambridge University library. The McClay holds the Queen’s Special Collections, including the Bunting manuscripts, and so has been extremely useful for me.

A library I have been involved with creating for over a decade now is that of the Historical Harp Society of Ireland; this library unfortunately remains merely a collection of books, since it has no librarian and no building. Maybe in time that will change.

There are other libraries which I would like to get access to. Another private library I have been in, but not used, is that at Clonalis House. There is Marsh’s Library in Dublin. And there is the curious local studies library at Benburb – it was closed when I visited, but I should try again.

I am sure there are others that I have missed…