Right from the very beginning of my harp studies I was fascinated by the idea of ceòl mór on the harp. I started studying the first tunes (Fair Molly, the Butterfly and Burns March) from November or December 1999, and I think it was just a couple of months later that I found a cassette tape copy of Ann Heymann’s Queen of Harps in an Oxford Celtic/New Age shop. That recording, apart from eternally smelling of patchouli, of course has Ann’s 30 minute performance of her version of the pibroch, Lament for the Tree of Strings.

I think I was taken by the intricate repetitiveness of the music, like a journey through a landscape, or perhaps more pertinently like the folded geometric patterns in medieval manuscripts such as the Book of Kells. I was also interested in the abstract nature of the tunes, which are very different from the more “tuney” tunes more commonly found in traditional music nowadays.

I made a page on my old website about ceol mor, where I searched for inspiration and information.

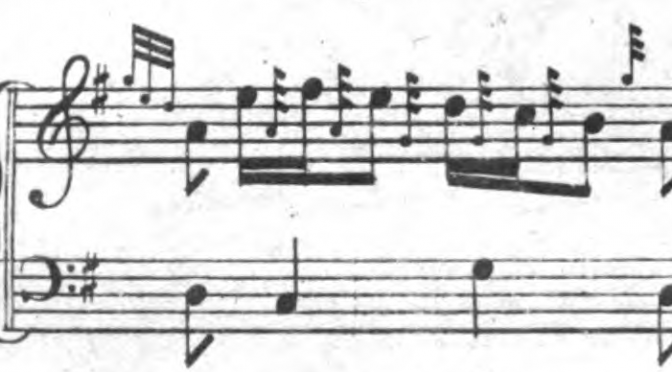

The first ceòl mór tune I played on the harp was Cumh Easbig Earraghaal, the lament for the Bishop of Argyll, the manuscript source for which is reproduced in Alison Kinnaird’s and Keith Sanger’s book Tree of Strings. I think it took me a long time to get to grips with this tune but in some ways it made perfect sense to me – this is exactly what ancient harp music is meant to sound like, the contrasts between the different variations, and the opportunities for exploring different timbres and idioms as the variations progress. I continued to play and develop this tune and included it on my first CD, Clàrsach na Bànrighe, in 2008.

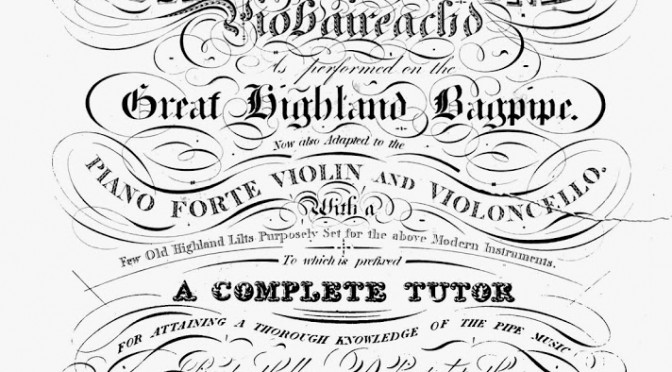

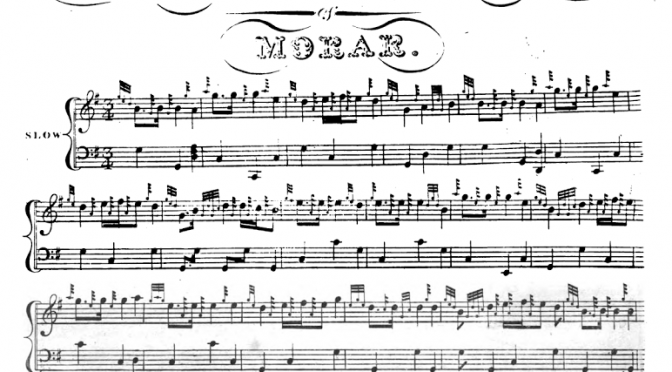

Ceòl mór is a genre of music that is best known nowadays as pipe music, played on the great highland bagpipe, where it is known as pibroch or pìobaireachd. I say “best known” though in fact you rarely hear pipers playing this type of music; it is rarely included in concert programmes, living instead in a rarefied world of piping competitions. I worked for a while with historical piper Barnaby Brown, on projects including promoting both piping and harping on the internet and developing online teaching resources. His unusual insight into the historical pibroch traditions gave me some useful understandings of the nature of this music and how it might live nowadays. Traditionally it belongs to the pipes and the fiddle and the old Gaelic harp with metal wire strings, and I feel each of the three instruments brings something different and unique to the music. None of them is “imitating” the other, each wholly owns the music and expresses some true deep spiritual essence of it in its own way.

I have continued to work on Gaelic harp ceòl mór; my latest CD Tarbh is entirely pibroch tunes (and I wonder if it is the first CD ever to be 100% harp ceòl mór). It is hard to market; it is serious music but it does fall between stools – too serious for traditional music followers, too traditional for classical and early music people. Pipers who play pibroch seem intruiged by it. When I perform concerts and include a big 10 minute ceòl mór tune, I am always nervous as to how the audience will react – will they be bored and restless? But afterwards I find people come up and say, that was the best piece of the whole concert!

Ceòl mór is such a huge world for me, I think I could spend the rest of my life just studying and playing this repertory. There is something truly meditative about the power of the music. More than one person has said how it is reminiscent of Indian Raga music, and I think it is the way that it selects just two or three notes and then cycles meditatively around them. There are points in some of the pibroch where a new tone appears and hits you with the force of emotion and power – I find it fascinating that such emotional intensity can be built up from such apparently simple material. Perhaps it has that intensity because of its deliberate, austere simplicity.