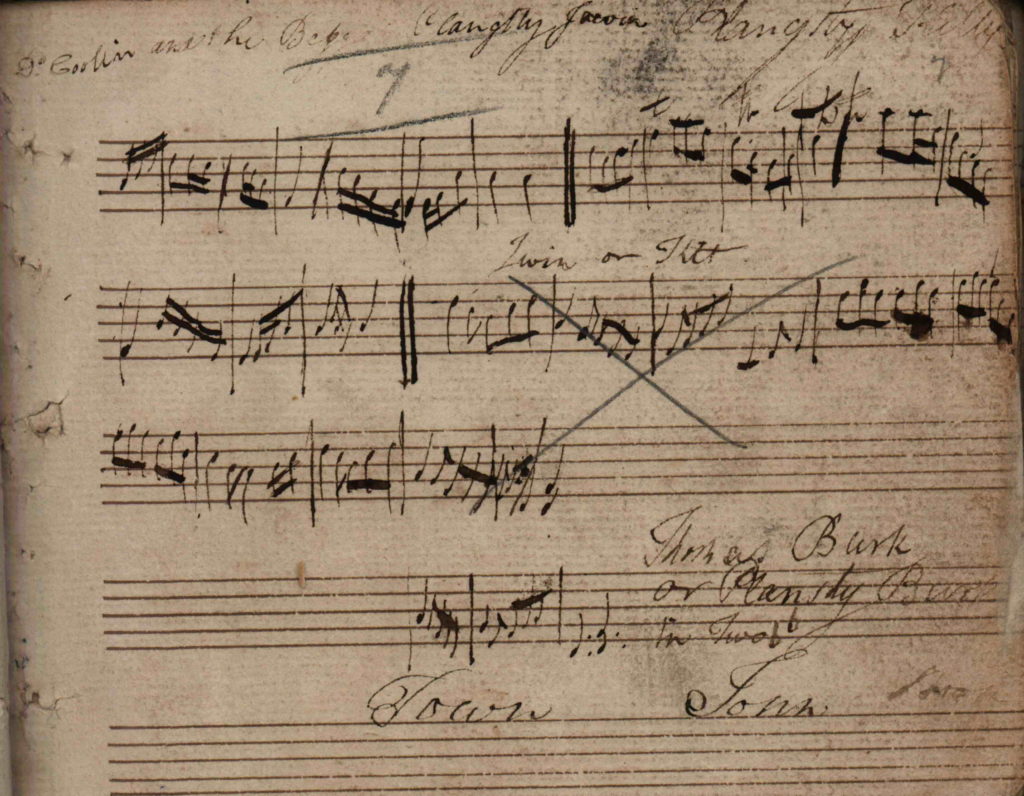

Edward Bunting wrote a notation into one of his little transcription pamphlets in the 1790s, showing two tunes (Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.29 page 7). I think these may be live harp transcription notations.

Just glancing at the notations you can’t see them as two different tunes; there are three sections of notation with two sets of double-bar-lines dividing them up. But we can recognise them as two different tunes; the first two sections of notation are the tune of “The Beggar”, and the third section of notation is the tune of “Plangsty Irwin”.

I’ll do a separate post on each of these tunes, starting with the Beggar.

At the top of the page Bunting has written “Do Coolin and the Begg[ar] / Plangsty Irwin / Planxty Kelly”. Above the third section of notation he has written “Iwin or Kit”; and at the bottom of the page he has written “Thomas Burk / or Plansty Burk / in Two ♭♭” and then a word written twice which may be “Town” or “John” – I am not sure. I think the “Burk” information relates to a different tune, as does the “Kelly” title at the top (there is a transcription of the tune of Planxty Kelly three pages later). I don’t know what “Do Coolin” might mean.

You can download my PDF typeset version of this tune, which I used to generate the machine audio.

My typeset version of the notation, and the machine audio, is transposed one note lower from the manuscript notation. This puts it in G major which is a plausible harp key for it. You can see from my tune list spreadsheet that all the harp transcription notations in this little pamphlet (from pages 3 to 12) appear to have been transcribed a note higher than they were likely played on the harp.

I would understand this notation to be a live transcription from a harper informant. I imagine Bunting first wrote the dots, as the harper played. Then I would think he went back and added note stems, beams, barlines, and the three “tr” marks in the second section. He struggles a bit with his barlines, and he has also deleted some notes, in bars 1 and 2 of the first half, and also bar 4 of the second half. He has mis-barred the 3rd and 4th bars of the second half; he writes in another barline and marks it as the correct one by putting a + at the top. There is a little extra note in bar 5 of the 2nd half; I have transcribed this as a gracenote but it may be just an abandoned tune note.

Bunting’s later classical piano arrangements

Bunting made a classical piano arrangement which seems to be based on this transcription notation. It is in his unpublished “Ancient and Modern” collection which I think was compiled in 1798, on Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.33.3 page 8. The title there is “Boccagh buoy nelemnigh – or the lame yellow beggar” and at the bottom of the page he has written “On the mountains high, from Charles Byrne”. He writes out the first section of the tune twice through, and he writes a repeat sign around the second half of the tune.

There are also four classical piano arrangements probably from the late 1830s and from 1840. Our tune appears in the two big piano albums which I think were part of the preparations for the 1840 published book. In QUB SC MS4.13 it is tagged “very ancient Author and date unknown / From Daniel Black the Harper in 1792″, and in QUB SC MS4.27 it is tagged “from James Duncan the Harper in 1792 / another name ‘all on the mountains high'”. I have not seen these manuscript pages and am relying on Colette Moloney’s introduction and Catalogue (ITMA 2000) for these tags. A similar arrangement appears without tags in QUB SC MS33.5 page 57 where it is titled “Baccagh buoy nelemne, the lame yellow beggar”.

Bunting finally published a classical piano arrangement as no. 20 in his 1840 book. The title there is “The Lame Yellow Beggar / By O’Caghan in 1650”. We can check the 1840 index; on page ii we are given the Irish title “Bacach buidhe na leimneadh – bacach buidhe na leimne – The lame yellow beggar”, and on page xi he writes “The lame yellow beggar – O’Cahan 1640 – D. Black, harper, 1792”

As usual we don’t need to pay any attention to these classical piano arrangements, except to collate the tune versions they are based on, with the attribution tags and other metadata they present.

Other versions of this tune

Our tune was printed in 1724 by John and William Neal, under the title of “Ye Bockagh”. It is on page 26 of their Colection of the most celebrated Irish tunes. The Neal version seems to be in a baroque violin setting, typical of the tunes in their book which was intended for perfomance on violin, transverse flue, or oboe by wealthy and literate urban baroque amateurs. Bunting had a copy of this book and would have been familiar with this version of the tune.

Title

I think the Neal version can be useful to us in confirming the overall shape of the tune, and the title “bacach” (beggar). We could read the header of our transcription on MS4.29 page 7 as originally reading just “The Beggar” and having the other text inserted before and after.

In his later piano arrangements Bunting consistently gives us the title “Bacach buí na leimne” He translates this as “the lame yellow beggar”. This full version of the title is also in tune lists on QUB SC MS4.29 p.37, “Boeeagh Beeog nelemma or Lame Beggar” and page 103 “Boccagh buoy Nellema”.

There are other “beggar” – related titles in Bunting’s transcription notebooks, including (above a completely different unrelated tune) on MS4.29 p.26 “Lame / Jolly Begarman” though it is not clear if these other titles refer to our tune or not.

Bunting also gives us the alternative title, “On the mountains high” or “All on the mountains high”. Again, this title only appears in the piano arrangements.

Attribution to Rory Dall

In the introduction page 91 of his 1840 book, Edward Bunting tells us about three tunes attributed to Ruaidhrí Dall Ó Catháin:

Bacach buidhe na leimne, or the “Yellow Beggar” (No. 20 in the Collection) is a third by the same eminent hand, and is said to have been composed by him in reference to his own fallen fortunes towards the end of his career

However, this line, and also the attribution in the 1840 index p.xi, and the heading to the 1840 piano arrangement, are the only attributions to Ó Catháin that I have found. This tune does not appear in any other description of Rory Dall’s music that I know of, such as the account of Rory Dall on the 1840 introduction p.82 which derives from Arthur O’Neill’s Memoirs.

It is also notable that the 1830s piano arrangements in QUB SC MS4.13 and MS4.27 don’t include a Rory Dall tag. Indeed, MS4.13 includes the standard tag “Author and date unknown” though this has been subsequently crossed out.

It looks to me like Bunting inserted this O’Catháin attribution at the very last minute. I do wonder where this information may have come from; it seems far too late to be derived from the harpers in the 1790s. Was this some kind of scholarly guess? Did he have information from an antiquarian correspondent?

Attribution to a harper informant

As usual, there is no attribution tag on the transcription manuscript (MS4.29 page 7). So we have to look elsewhere for suggestions as to who Bunting transcribed this from.

Presumably in 1798, a few years later, Bunting associates this tune with the harper and singer Charles Byrne. However, by the late 1830s, we have two other names claimed to be the source of this version of the tune: Daniel Black, and James Duncan.

I don’t really know how we can go about working out which of these we believe. It is of course possible that Bunting made three separate transcriptions of similar versions of the tune from each of these three harpers; but the particular transcription we are looking at on page 7 probably derives from the playing of a single informant on a single occasion.

I tend to believe earlier attribution tags, and be more suspicious of later ones – the Duncan and Black names are being added to versions of the tune perhaps 45 years after the collecting session. How did Bunting recall or record a supposed association? We don’t have tune lists where he kept records of who gave him what.

The next tune transcribed on MS4.29 page 7 (Planxty Irwin, subject of my next blog post) also has conflicted tags (see my tune list spreadsheet). It is attributed to Charles Byrne on the previous page 7 of the 1798 piano manuscript, but in the early 1840s it is being attributed to Hugh Higgins in the annotated prints. Does this confirm my suspicion that the 1830s-40s attributions are basically unreliable and invented? Was our tune collected from Charles Byrne? I don’t know.

Other songs and tunes which might be vaguely related

As you can see from all the above, we don’t have very much context to be able to connect this tune into wider tradition. We have the tune itself, and we have the two alternative titles “Bacach buí na léimne” and “On the mountains high”. There are any number of tunes or songs whose titles include the word “beggar” or “mountain”, but I am not convinced that any are “the same as” our tune. I especially note that none of the “beggar” songs include our full title or text “bacach buí na leimne”. But we can glance at a few just for context and comparison.

There is a song which is sung in the tradition today under the title “Bachach buí na Léige”, which begins “A bhacaig bhuidhe na léige, leig dod’fáidhte béil dam”, with a chorus starting “teidlídléró”. Donal O’Sullivan (Bunting 1983 p.34) printed our tune under this title but I think that must be a mistake.

Patrick Lynch collected a set of words in Mayo in 1802, which seem to me to be a relative of this song. Lynch’s neat copy of the words are in MS4.7 p.134. The title given there is “Bacach” and the song begins “Eirigh a mhaire is gleas na mala…” and the chorus begins “An bhuil tú sasta…”. Lynch’s English translation of this text is in QUB SC MS4.32 p.22 beginning “Rise up Molly, fix the wallets”. However, Lynch very rarely gives us a clue about what tune any of these songs were sung to.

A second song written out by Lynch in 1802 also titled “Bacach” is on MS4.7 p.97. This one begins “Ta mo chúrsa deanta agus mo shaidhbhris…”. Moloney’s Catalogue p.302 lists another copy of this text (which I haven’t seen) in QUB SC MS4.25, written by Lynch in 1802, and tagged by him “J Knucle” (who is identified on the previous page as Jack Knuckle, Balcara, 4 miles from Castlebar). Lynch’s English translation of this text is in QUB SC MS4.32 page 116 and begins “My course is cut out for me and my wealth extends through Ireland”. Donal O’Sullivan (Bunting 1983 p.34) printed these words under our tune, but I don’t see any real rationale for making such a connection. As usual, Lynch gives us no clue as to the tune used for these words.

A third different song text written out by Lynch and titled “Bacach Buidhe” is in QUB SC MS4.16, beginning “Is meanra a threaigas a [?] no a cheile…” but I haven’t seen this. See Moloney (2000) p. 274.

In his Journal (QUB SC MS4.24 p.51) Lynch indicates two different songs which he collected “at John Gavans”; “Bacach” and “Bacac Buidh”. But I can’t work out which title refers to which text.

“On the Mountains High” seems to be a title that is related to the English-language ballad Reynardine; one of the tunes that variants of this ballad are still sung to is “The Mountains of Pomeroy” (played here on concertina by Noel Hill):

While there is a vague resemblance with our tune, I think they do turn differently.

Many thanks to Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections for the digitised pages from MS4 (the Bunting Collection), and for letting me use them here.

Many thanks to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for helping to provide the equipment used for these posts, and also for supporting the writing of these blog posts.

I did a Youtube of The Beggar along with Planxty Irwin, based on this manuscript page. This was done back in January 2020, before I had properly started this Old Irish Harp Transcription Project. I did not really understand how to approach the transcription notations. It was also before I started working with Sylvia Crawford’s interpretations of the old Irish harp playing techniques, and so both my arrangement and my fingering techniques are rather stilted and unconvincing.