In Part 1, I wrote about Patrick Byrne’s early years and education. Then in Part 2, we looked at his early career, working for patrons in Ireland and England.

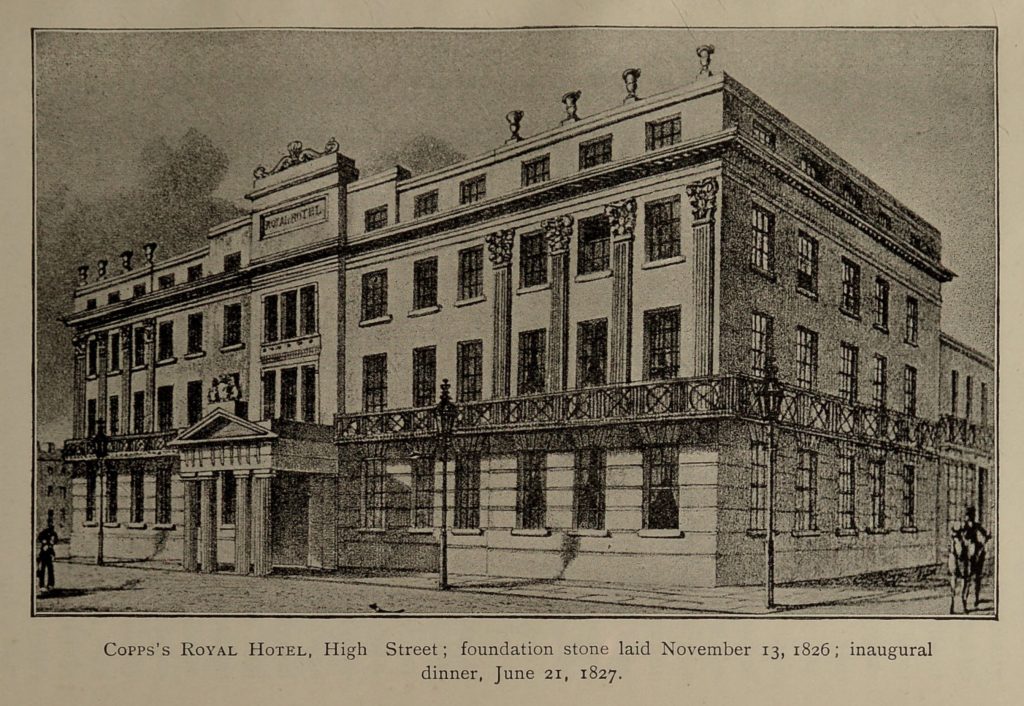

By the summer of 1837, Patrick Byrne was approximately 40 years old; he had made a lot of contacts amongst the English and Irish aristocracy, and he had proved himself by his regular job at the rather high-class Royal Hotel in Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, England.

We will continue the story on Wednesday 18th October 1837, when Patrick Byrne left Leamington Spa and began the journey North to Edinburgh.

Mr. PATRICK BYRNE, whose performances on the Irish Harp have won him “golden opinions” among the best judges, left his warm-hearted friends at the Royal Hotel on Wednesday, for Scotland; where his professional engagements at the residence of many distinguished noblemen and gentlemen, will occupy his attention for the ensuing three months. We have no doubt, that his melodious strains, which occasionally display some novel and striking features, will meet with a success amongst the sons and daughters of Caledonia, equal to that which his taste and execution ensure him in this country. – After visiting the North, Mr. Byrne again returns to his friends in Warwickshire.

Leamington Spa Courier, Sat 21 Oct 1837, p.2

Patrick Byrne was in Edinburgh from the end of October 1837 through to February 1838. He did not perform any public concerts, but spent his time in private houses, playing for aristocrats and wealthy people and for their private parties. Because of this, our information about his trip doesn’t tell us exactly what he was doing or give us any kind of itinerary, but we do have statements about some of his main patrons on the three-month trip, and we also have some very evocative and informative extended descriptions of his playing.

Patrick Byrne’s patrons in Edinburgh

The Leamington Spa Courier, Sat 24 Feb 1838, p2, (see below) tells us who were the patrons that Byrne was working for when he was in Edinburgh over the winter of 1837-8. It appears that the trip was instigated or mainly organised and hosted by John Spottiswoode (1780-1866) of Spottiswoode House. He was a historian who published the medieval Registers of Dryburgh Abbey in 1847, and who also bred an enormous ox. Spottiswoode House is about 30 miles south-east of Edinburgh; presumably he also had a town house in Edinburgh but I am not finding where this would have been. I imagine that Byrne would have stayed in the city rather than 30 miles out in the countryside.

We are also told (The Scotsman, Wed 24 Jan 1838, p3) that Patrick Byrne “has recently been on a visit to the Duke of Buccleuch”. This would have been Walter Francis Montagu Douglas Scott, 5th Duke of Buccleuch, 7th Duke of Queensberry, and I think it is most likely that Patrick Byrne went to stay at Dalkeith Palace about 7 miles south-east of Edinburgh. The 5th Duke was very highly placed in the British aristocracy, and hosted Royalty at Dalkieth. You can read more about him at Our Edinburgh Friends.

The Leamington Spa Courier also mentions Patrick Byrne being patronised by Lord John Scott and his wife, Alicia Ann, Lady John Scott. Lord John Scott was the younger brother of Walter the 5th Duke; Alicia was the daughter of John Spottiswoode, and is famous for composing the song air Annie Laurie. They lived at Cawston Lodge in Warwickshire, about 12 miles from Leamington Spa. They also leased Caroline Park near Edinburgh but I don’t know if they had this house in 1837-8.

Descriptions of Byrne in Edinburgh

We have a few extended descriptions of Byrne’s activities in Edinburgh over the winter of 1837-8, from the Scottish newspapers:

MR. BYRNE, THE IRISH HARPER. – Mr Byrne has been for some weeks in Edinburgh, chiefly engaged in performing in the evenings before private parties. We had the pleasure of meeting him a few nights ago, and have rarely experienced a musical treat of so interesting a kind. His instrument is the genuine harp of old Ireland, strung with thirty-seven brass wires, of course without pedals, and arranged in such a way that the tenor is played with the left hand and the bass with the right. The musician, now in middle age, has been blind from infancy, but possesses an intelligent mind, joined to pleasing and modest manners. He received his musical education in the academy established in Belfast for keeping up the use of the harp; and for the last twelve years has been chiefly resident in England. Mr Byrne was, we understand, induced to visit Scotland at the solicitation of some distinguished individuals who had heard his performances in the South. He has recently been on a visit to the Duke of Buccleuch, in whose halls he must have been a peculiarly appropriate object, as his appearance there could scarcely fail to recall the minstrel who erst solaced the dame, who,

The Scotsman, Wed 24 Jan 1838, p3

“In beauty’s bloom,

Pined over Monmouth’s early tomb.”

Mr Byrne, indeed, completely realizes the vision of the ancient minstrel. He plays with an enthusiasm which brings Carolan and his predecessors before the eyes of the audience. We observed that there is also a national peculiarity in his style, like the accent in speech – a certain wild plaintiveness which probably no-one not “to the manner born” could imitate. We never before were sensible of the full effect of Coolun, Savournah, Kitty Tyrrell, and other slow tunes of the same class; nor did our hearts ever dance in the same frolicsome measure to the Planxties and other quick airs, which form a striking contrast with the others. The combined effect of the music and the musician, in a quiet evening party, is altogether remarkable, at once filling the ear with divine melody, and the mind with sweet and pensive memories of the days of old.

This article was reprinted, for example in the General Advertiser for Dublin and All Ireland Sat 3 Mar 1838 p4. The lines about “the minstrel who erst solaced the dame” are from Sir Walter Scott’s 1805 poem The Lay of the Last Minstrel, which was based loosely on the Buccleuch family history. Sir Watty (1771 – 1832) had been the guardian of Walter the 5th Duke of Buccleuch during the Duke’s youth.

The description of Byrne’s playing is a bit romanticised, but we can extract some real information here. I think we can understand that the listeners perceived two different types of music, the “slow tunes” (I think we would say slow airs nowadays), and the “planxties and other quick airs”. Three titles of slow airs are given; and all three are still well-known in the tradition today. Here’s Joe Ryan playing “Coolun” on the fiddle:

Here’s Leo Rowsome playing “Savourna” on the pipes:

And here’s Aoife Ní Fhearraigh singing “Kitty Tyrrell”:

At the moment I don’t have much to say about the “quick airs” but we can keep them in mind.

THE HARP OF THE LAST MINSTREL. – Mr Byrne, the celebrated Irish harp player, a genuine representative of those “who once in Tara’s halls, the soul of music shed,” is at present on a visit to Edinburgh, where he has been warmly received, and much sought after by the most respectable circles of society. It is quite refreshing – it gives a sort of phillip to our musical ideas, as well as our historical and antiquarian reminiscences, to see this living relic, as it were, of by-gone ages, and to hear him strike, with a master’s hand, that harp, of which Bacon said, that no other harp had a “sound so melting and prolonged,” and to which Drayton paid the following tribute: –

Caledonian Mercury, Sat 27 Jan 1838, p3

“The Irish I admire

And still cleave to that lyre,

as our muse’s mother;

And I think, till I expire,

Apollo’s such another.”

Well, Apollo could scarcely have got a better instrument; and had Irish harps been known in hi[s] godship’s days, he would have laid aside his “lute,” musical as it is said to have been, and betaken himself to a thirty-five stringed instrument. Having enjoyed the pleasure of hearing Mr Byrne, we can bear unqualified testimony to the fact, that his performances have not been in the least degree over-rated by his countrymen – that he reigns over the strings of the harp as supremely as ever did magician over his familiars – and that the effect which he produces is at once refined, striking, and uncommon. Mr Byrne sacrifices nothing to manual dexterity, but makes everything subservient to the pervading spirit – the soul of the melody which he is executing; and his rapt look, which people of old, probably with perfect propriety, calls inspiration, shows that whilst his flying fingers sweep the strings, his mind is busier still, completely concentrated in the music, and carrying and carried along by it. Every one knows that Irish airs have a peculiar charm, arising as much from modulations into the minor mode being frequent, thus deeply tinging them with melancholy, as from their other intrinsic merits, which all the world knows are of the highest order. It is doing no more than justice to Mr Byrne to say, that we never before heard them performed so much in the true spirit in which they were composed; more we could not say. For the satisfaction of phrenologists we may state, that in the minstrel’s head the organ of tune is prominently developed.

The reference to Bacon’s famous description of the sound of the Irish harp is very nice! I am less sure what the verse by Drayton is about. Both were cited by Thomas Moore in 1837 which is I guess why they were current at that point. The phrenological information reminds us of Darby Fegan’s description of Valentine Rennie feeling the “musical bumps” on Alex Jackson‘s head.

We also have a retrospective description of Byrne and his performances from a couple of years later. This is part of a long article in Chambers Edinburgh Journal, as a kind of extended book review of Edward Bunting’s 1840 Ancient Music of Ireland. The relevant passage begins as a corrective to Bunting having published McAdam’s deadly letter advocating the abandonment of the inherited tradition of playing the traditional wire-strung Irish harp, and defunding the Belfast harp school.

…We feel most reluctant to accord with this view of the subject. If we could judge at all from one instance, we would say that an Irish harper may yet be a respectable person. A worthy representative of the fraternity, Mr Patrick Byrne, a pupil of the Belfast Academy, makes a livelihood by playing to parties at Leamington. He is a well-informed, modest, and agreeable man, of perfectly virtuous habits, as well as a delightful performer on his instrument. We had the great pleasure of hearing him about three years ago in Edinburgh, where he attended private parties for a moderate fee, and was generally esteemed. Why may not other blind youths be reared to the same walk in life, and conduct themselves with equal propriety? Any thing rather than that so beautiful an instrument should perish from the face of the earth.

Chambers Edinburgh Journal, no. 451, Sat 19 Sep 1840, p279

Let it not be supposed that the Irish music may nevertheless be preserved and played on other instruments. No one who has heard the Irish harp could imagine such a thing. When we hear Sir John Stevenson’s Irish Melodies played by a young lady on the piano-forte, or even on the pedal harp, we do not hear the same music which O’Cahan, Carolan, and Hempson played. It is as much altered as Homer in the translation of Pope. For the true presentment of this music to modern ears, we require the old sets as preserved in the volumes of Bunting, and the Irish harp played by an Irish harper. This instrument, it must be remembered, is of peculiar structure. It contains about thirty brass wires, the twang of which give the music a striking metallic brilliancy. The high notes are given with the left hand, reserving the more powerful member for the deep chords of the bass. There is moreover – at least so we found it in Mr Byrne’s playing – a certain national accent, like the tone in speech, given to the music by the Irish performer, which everyone must recognise as extremely interesting, both from its real beauty and from association…

This is a fascinating pen-portrait of Byrne and it is also very significant for understanding the politics of the place of the Irish harp in musical life in the mid-19th Century. We will talk more about that below when we get to the publication of Bunting’s 1840 book.

Keith Sanger found a couple of Scottish newspaper clippings which I have not seen; they are referenced in his 2006 online biography of Patrick Byrne. Sanger says that the clipping from the Edinburgh Advertiser Tue 19th Dec 1837 includes a long description of Byrne’s performances. Sanger also says that the Edinburgh Advertiser Tue 16 Jan 1838 mentions Byrne being about to take his leave of Edinburgh, though we can see from the clippings above that he remained in Edinburgh some time after that.

Learning to read

Perhaps one reason that Patrick Byrne did not leave Edinburgh in January 1838, but stayed on a few more weeks into February, was because he was learning to read. We have a letter from the Rev. Dr. Paterson in Edinburgh, sent to the British and Foreign Bible Society:

Feb 1, 1838

Monthly Extracts from the Correspondence of the British and Foreign Bible Society, No.59, 31st March 1838, p565

…We have a Blind Irish Harper here at present, the tips of whose fingers are hard as horns with touching the strings of his harp, who is taking lessons from Mr. Gall in reading, and getting on amazingly well…

This is obviously Patrick Byrne; I don’t think there was a second blind Irish harper in Edinburgh in January 1838.

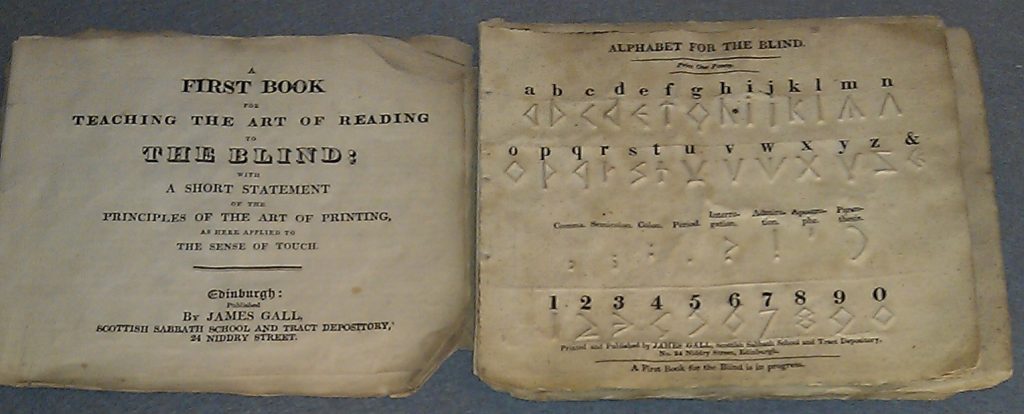

James Gall (1784–1874) was an Edinburgh publisher and religious activist, based on Niddry Street. In the 1830s he was working on publishing religious books printed in embossed letters, designed for blind people to be able to read them by touching the raised letters with their fingers. At this time there were different competing systems; the Braille system had been published in 1829, but many educators in Britain and Ireland at that time preferred systems based on raised conventional letters. Gall’s system was described: “the characters of which are generally recognisable to common readers, the form being angularised Roman, some higher, some lower-case. Four letters of the whole are incognisable to an ordinary person. The size is 3-16ths of an inch full” (Robert Hugh Blair, Education of the Blind, reprinted 1876, p5).

I don’t think it would take long for Patrick Byrne to learn to read these embossed letters, perhaps only a week or two; and presumably he took some books away with him, because after his death his list of belongings includes “4 Books for the Blind” valued at 5s. (Evelyn P. Shirley, list of Byrne’s effects dated 29 Sep 1863, PRONI D3531.G.6). I understand that Gall’s system never really caught on outside Edinburgh.

Apart from religious-themed education material, titles we know that Gall published in this embossed lettering include John (1832/4), Ephesians (1835/7), Acts (1838), and Luke (1838). Of course we don’t know which specific titles Byrne had. But I think being able to read, and only having four of Gall’s books, would have had a big effect on Byrne, probably making him more religious. This is just a guess.

As an aside, we have a reference to the traditional harper Samuel Patrick learning to read embossed books in Belfast in 1864, again in a religious context.

Leaving Edinburgh and returning to Warwickshire, 1838

By the second half of February 1838, Patrick Byrne was back in Leamington Spa.

MR. BYRNE, THE HARPER. – Our readers will be glad to learn that Mr. Byrne, the blind harper, has returned to Leamington for a few weeks, and is again to be found “striking his wild chords” in his old quarters at the Royal Hotel. Mr. Byrne met with the utmost success during his sojourn in Edinburgh; indeed, the kind manner in which J. Spottiswood. Esq., of Spottiswood, took him by the hand, ensured for him an hearty welcome in the halls of the Scottish nobility. Among the more distinguished of his patrons, we may enumerate Lord and Lady John Scott, and their noble relatives, the Duke and Duchess of Buccleuch; in whose halls the harper must have been a peculiarly appropriate object…

Leamington Spa Courier, Sat 24 Feb 1838, p2

…[brief quotation from the Scotsman, not attributed]…

The Caledonian Mercury, speaking of Mr. B., says –

[long quotation from the Mercury article]

The following lines, with which we have been favoured with a copy, were written, on hearing Mr. Byrne play in the hall of the Royal Hotel, by our talented friend Mr. J. E.. CARPENTER, the author of “Minstrel Musings”…

…[praise of the poet, and then poem of 42 lines beginning “Strike old Harper – strike the lays / Of those – the old romantic days…”]

This article says he will be back in Leamington for “a few weeks”, but I don’t have any more references to his movements for the following six months. In July 1838 he is in the Royal Hotel in Leamington Spa. I don’t know if he stayed working in the Royal Hotel for those six months, or went off to visit Warwickshire patrons such as Shirley at Ettington, or what:

Mr. BYRNE, the blind Irish harper, still continues to delight the distinguished visitors at Copps’ Hotel, by his performance of many beautiful melodies of his native country.

Leamington Spa Courier, Sat 28 Jul 1838, p2

There is still a great lack of information after that about Byrne’s movements. My guess is that he stayed in Warwickshire but I don’t know.

In his private papers (Belfast, PRONI D3531.G.3) there is a handwritten poem dated 16 Aug 1838, on the coronation of Queen Victoria. She had become Queen on 20 June 1837, but her coronation was not until 28 June 1838. The poem is signed John Keating 19 Shaw Street, Liverpool; it is titled “Mr Barney Maguire’s History of the Coronation” and begins “Och the Coronation! What celebration / in emulation can with it compare?…” The poem is folded small but I did not find an envelope that matched it. This comic song was written to the tune of “The Groves of Blarney” as part of the Ingoldsby Legends by Richard Harris Barham. I don’t know who John Keating was or his connection to Byrne.

It looks like Patrick Byrne spent Christmas 1838 with the Shirleys at Eatington Park, in Warwickshire.

In Ireland, 1839

Byrne left Eatington Park on 2nd January 1839, to travel to Ireland. In his private papers there is a letter of recommendation written for him by Eliza Shirley, the day before he left. Its envelope is addressed to Mrs. Filgate, Lisrenny. Eliza Shirley writes on gilt-edged notepaper:

Eatington Park

PRONI D3531.G.1

Jany 1st 1839

Dear Mrs Filgate,

The bearer of this Mr Patrick Byrne, a blind Harper, has begged me to give him a few lines of Introduction to you, tho’ I believe he is known to Mr Filgate. We have been acquainted with him both in England & Ireland now for many years, & have ever found him a very quiet civil man. & I think you will / be pleased with his performance on the Irish Harp. He leaves us for Ireland tomorrow, & is likely to be in your neighbourhood towards spring or summer. Hoping he will find you, Mr Filgate & yr. Children all quite well, believe me most truly yrs.

Eliza Shirley

Mrs Filgate was Sophia Juliana Penelope de Salis, daughter of the 4th Comte de Salis. She lived with her husband William Filgate at Lisrenny House, which is in County Louth between Dundalk and Ardee.

Perhaps the most interesting thing here is that Byrne carried this letter in its envelope with him to Ireland, but he never passed it on to Sophia Filgate. Perhaps he never got there; or perhaps she read it and let him keep it. Either way it was still with his private papers when he died, which is how it is still preserved today.

I think that Patrick Byrne would travel with promotional materials as well as letters of recommendation. Soon after he got back to Ireland, we find two different newspapers re-printing the poem by J.E. Carpenter which was originally printed in the Leamington Spa Courier on Sat 24 Feb 1838. The poem is reprinted in the Belfast News Letter Tue 29 Jan 1839 p4, without further comment. I imagine Byrne bringing a news cutting of the Leamington Spa Courier with him and passing it on to the Newsletter office.

In Belfast with Dr. McDonnell

We don’t have specific details of where Byrne was between January and March 1839, but it looks like he may have been to Belfast, where he spent a day with Dr James McDonnell.

Dr James McDonnell wrote a letter to Edward Bunting in Dublin. The letter is postmarked 30th April 1839, but the meeting he describes with Byrne was before then; presumably before mid-March.

Dear Bunting,

Letter from Dr James McDonnell, 30 Apr 1839. Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, ms4.35.23 (published in Charlotte Milligan Fox, Annals of the Irish Harpers (1911) p. 135-6).

Since hearing from you, I have learned from Pat Byrne, a Harper, that all Harpers prior to O Neill, having taught only through the medium of Irish, must have had names for all the strokes, or Chords on the harp – The strings which are octaves to the Sisters he said had others which were called “Gilli ni fregragh ni Haulai” the servants of the answers to the sisters – He says that Miss Reilly of Scarvagh is the only person, whom he knows, now living who was taught to play thro the Irish language and he will endeavour to to collect from her some technical terms – he spent a day with me & I brought Alexr Mitchell to hear him…

But really we can’t date Byrne’s meeting with Dr McDonnell at all securely. This letter is full of very interesting information, but it also reads a bit waywardly, as if James McDonnell is garbling or misremembering his conversations with Byrne. The visitor, Alexander Mitchell, was a famous blind engineer who also had a strong interest in Irish music. I have discussed before the possible identity of the harper who learned through the Irish language: I suspect that the “Scarvagh” information is interpolated and wrong, and that Byrne may have been referring to Bridget O’Reilly who had learned the harp from Arthur O’Neill apparently in about 1793. Anyway it is a nice snapshot of Byrne remaining in contact with other harpers. The Irish terminology that McDonnell reports is a bit garbled; we do have the words giolla, freagradh and comhluighe from other harper sources, but not in this specific compound form. I don’t know if it was Patrick Byrne who was mixing the words up, or perhaps more likely Dr. McDonnell was.

It is also possible Byrne was in Greaghlone visiting his family; his half-brother Christopher was aged about 5. I discuss his family more in Part 1.

In Newry, March – April 1839

Anyway, by mid-March, a couple of months after arriving in Ireland, Byrne was in Newry.

THE IRISH HARP. – The lovers of genuine ancient Irish Music, will be delighted to learn that Mr. BYRNE, the talented performer on the Irish Harp, has favoured this town with a short visit, at Mr. Dransfield’s hotel; and as his stay will be very short, the opportunity of hearing his superior performance should not be lost sight of by those who admire native talent.

Newry Telegraph, Sat 16 Mar 1839 p3

John Dransfield ran the Commercial Hotel at 36 Hill Street, Newry (New Commercial Directory 1840 p.58). Number 36 is now the Catholic Working Mens Club, but I don’t know if the street has been renumbered since 1839. You can look on the street view anyway.

Three days later the Newry Telegraph reprinted the Carpenter poem, along with a little footnote:

(Mr. BURNS is now in Newry, and we have had the pleasure of hearing him “strike the harp of the olden time.” We understand he was instructed by the celebrated RENNIE, and, in our humble judgment, we think the pupil not likely to bring discredit upon the skill of the master. – ED. N. T.)

Newry Telegraph, Tue 19 Mar 1839 p4

Public concert, April 1839

After staying in Newry for a month, presumably playing private engagements, Patrick Byrne advertised that he would perform a public concert. I think this is the first time I have seen him doing a concert like this, as opposed to playing private events for Gentlemen or aristocrats, or visiting them at their homes.

The advertisement is headed by a woodcut of a heraldic “winged maiden” Irish harp. I wonder whose idea this was, if the newspaper owned the wood block or if Patrick Byrne owned the block and gave it to the newspaper office? We know that he later owned a custom-made woodblock of his own harp. Perhaps this is an earlier attempt to give himself a visual “branding”.

MR. BYRNE,

Newry Telegraph, Sat 13 Apr 1839 p3

The celebrated Performer on the Irish Harp,

RESPECTFULLY announces to the LOVERS OF HARMONY, that he purposes to have a Public Performance at the ASSEMBLY ROOMS on TUESDAY Evening the 16th instant.

Tickets of admission: – Price 1s. 6d., to be had at the TELEGRAPH Office,, or at Mr. DRANSFIELD’S Hotel.

N. B. – Doors to open at half-past Seven, performance to commence at Eight, and continue till Ten o’Clock.

The same advert was printed in the Newry Telegraph on the day of the concert, Tuesday 16 April 1839, with the header “THIS EVENING.” I can’t work out where the Assembly Rooms were in 1839.

In Armagh, April – May 1839

The following week, Patrick Byrne travelled from Newry to Armagh.

THE IRISH HARP. – Our friends in Armagh will be glad to learn that Mr. BYRNE, the celebrated performer on the Irish harp, is now in their City; and we are persuaded they will not fail to take advantage of the opportunity thus afforded them, to hear that instrument played by the hand of a master. They cannot patronise Mr. BYRNE more liberally than he deserves.

Newry Telegraph Tue 23 Apr 1839 p3

I am not entirely sure what the “town hall” refers to, because as far as I was aware there was no town hall in Armagh in the mid 19th century. The concerts may have been upstairs in the Market House (where the public library is now), or in the Tontine Rooms (where the North-South Ministerial Council is now, opposite the Charlemont Hotel).

It looks like Patrick Byrne spent three weeks staying in Armagh city at the end of April and the first half of May 1839. It seems that he played at least one concert in the town hall as well as playing private engagements for wealthy people at their houses, but I have not found any adverts or notices of the concert.

MUSICAL ENTERTAINMENT IN ARMAGH.

Newry Telegraph Tue 14 May 1839 p3

[FROM A CORRESPONDENT.]

The celebrated blind harper, Mr. BYRNE, has for the last few weeks delighted the citizens of Armagh, and afforded to the lovers of minstrelsy a rich and rare gratification, by his exquisite performance on the harp of Erin. As he is now on the eve of departure from our City, it is but justice to the unrivalled merits of this distinguished musician, thus publicly to state, that in all his exhibitions, both in the Town-hall and in private families, he received the warmest applause from enraptured auditories. He is, indeed, a consummate master in his art; and it would be difficult to express the deep and thrilling sensations which vibrated in the breasts of his audience as, “with flying fingers,” he sweeps the strings of our National instrument, and pours forth strains of melody and music, calculated to awaken ten thousand associations of other years. In addition to his skilful execution on the instrument, he has a thorough knowledge of the Irish character, and is intimately acquainted with the traditional legends of our country during those feudal times when the Minstrel, with his harp, was received with honor in the palaces of Royalty and in the baronial halls of proud Chieftains. He is thus enabled to impart to the tones of his lyre a pathos and a power which captivate the hearts of the auditors, nor can they get relief from these struggling emotions until the wizard that enchants them dissolves the spell. In a word, the Irish harp, when touched by the fingers of Patrick Byrne, realizes that beautiful creation of the poet’s fancy, the magic shell, and gives appropriate expression to every passion of the human breast. Whether we wish to excite our softest sympathies and throw over the soul a chastened sadness, or to awake the extacy of joy within our bosom, we have but to touch the strings and responsive notes vibrate upon the ear; or, should we strike his harp to the “stern minstrelsy of war,” the soul is electrified, and with notes as inspiring as ever summoned the fierce clansmen of rival chiefs to the field of fight, when the death cry of “Lamb derg abo” reverberated along the hills of Ulster. Mr. Byrne leaves Armagh with the best wishes of all who had the pleasure of / of hearing him, and they look forward to a renewal of that pleasure the next time he visits this part of the country.

Φ.

Who knew that the people of Armagh were so emotive and passionate? I am actually not sure how to take this kind of newspaper clipping. It looks to me like this is less reportage and more like “product placement”, like an agent or a patron or a fan of Patrick Byrne wrote and submitted this as a kind of promotional press release. There are a couple of typos towards the end (“of” and “lámh dearg abú”) – perhaps the author’s handwriting got more and more excited and scratchy and hard to read as they went on. The article is signed by the pseudonym “Φ”; I don’t know if it is possible to work out who this might be.

After this, there is a gap in the records for six months, from May to November 1839. Perhaps Patrick Byrne went to Lissrenny to stay with the Filgates. I really don’t know. By mid-November 1839, Patrick Byrne had arrived in Tandragee.

In Tandragee, Nov 1839

THE IRISH HARP. – Our Correspondent informs us that Mr. Byrne, the celebrated Irish Harper, has been for the last ten days in Tandragee, and that the inhabitants of the town and neighbourhood have been much delighted with his performances, which are universally admitted to possess that chasteness and correctness of expression, which even adds a charm to Irish music. We believe he intends to visit Armagh.

Newry Telegraph Sat 30 Nov 1839 p3

We have another six months gap between December 1839 and May 1840, when I have not yet found any references to what Patrick Byrne was up to.

In Dublin, May 1840

In mid May 1840, Patrick Byrne arrived in Dublin. I don’t know that he had actually stayed in the Capital before now, though presumably he may have passed through on his way back and forward from England to Ireland. Or he may always have travelled via Belfast. I am not sure about the routes that people would have taken in those days.

Mr. PATRICK BYRNE, the celebrated Irish Harper, from the county of Monaghan, who has been long patronised by Mr. SHIRLEY, M.P., and several of the nobility and gentry, has arrived in town, and intends to sojourn amongst us for a short time. Mr. BYRNE is in great request in the higher circles in this city, and will perform in private at the houses of some of our leading fashionables during the next fortnight; but he is not yet decided as to whether he will perform in public. To the visitors of Leamington Mr. BYRNE is well known, though in the metropolis of his native country he is almost a stranger.

Dublin Evening Packet and Correspondent p3 Sat 16 May 1840. (Reference from Catherine Ferris, The Use of Newspapers as a Source for Musicological Research: A Case Study of Dublin Musical Life 1840–44 (PhD Thesis, Maynooth 2011, p53)

At about this time Patrick Byrne must have met Edward Bunting, since Bunting wrote a letter of recommendation for him four days after this newspaper notice. The letter is preserved in Byrne’s private papers. We can think about the dynamic here; the elderly Bunting had just finished his monumental publication, The Ancient Music of Ireland, and was waiting for it to come back from the printers and publishers; Bunting wrote on 9th May 1840 “my very last sheet is now printing off, and we expect to be able to publish in the course of a fortnight” (Fox, Annals p304).

Bunting’s book had revisited his collecting work from over 40 years previously, in the 1790s; and while Bunting had been involved with the first Irish Harp Society school in Belfast in around 1810, he was already in Dublin by 1820 when the second school started, and he only seems to have a limited involvement with the preparations in 1819 (including ordering the wrong kind of harps). He had not worked on the Irish music for years, until in the late 1830s he had been persuaded by Dr James McDonnell to gather his materials and complete the 1840 book.

Bunting’s 1840 book is a very troubling work, since it effectively seals the fate of the inherited tradition; not only by totally ignoring any harper who wasn’t already old in 1792 (Bunting studiously avoids mentioning William Carr, Patrick Murney, or any of the others), but most damningly by publishing McAdam’s letter advocating the defunding of the harp school, and announcing that the inherited tradition was not worth supporting or continuing, because the remaining harpers were too low-class and degenerate. And remember that Dr McDonnell had also written Bunting a letter in 1839 arguing for the value of the continuing tradition, and naively hoping that Bunting’s book would support the promotion and continuation of the school. But Bunting chose not to publish any of that.

Did Bunting have regrets when he met Byrne, even as the awful book was being printed? Did he realise what he had done in the book? Did he write Byrne the testimonial in a futile attempt to atone for his betrayal of the continuing harp tradition?

The letter is folded to make a small packet and addressed on the outside (the back of the unfolded sheet)

For

Mr. Patrick Byrne

Professor of the

Irish Harp

The letter reads:

May 20th 1840

PRONI D3531.G.1

45 upper Baggott St. Dublin.

Dear Sir,

I am happy to have it in my power to bear testimony to your competence as an Irish harper. Your having received your musical education in the school of the Belfast Irish harp society, where you were taught to play according to the method of the ancient harpers is a great advantage, and I conceive it to be a matter of much moment that we should have in you a performer yet remaining capable of giving due effect to the [primitive] airs of our country. Your being able to accompany them with your voice in the words of their native language cannot fail in giving pleasure to those who delight in the simple and beautiful music of Ireland, which has been celebrated for so many ages.

I consider you especially well qualified to give those sweet melodies their proper effect by playing them in that extremely soft and whispering manner which can perhaps be best executed by the delicately sensitive touch of a person deprived of sight. This part of your [performance] I recommend to the attention of your auditors, as also that in which you stop the vibrations of the strings &ce. In these two particulars <you show> to advantage the remains of the distinguishing characteristics of our national performance on the harp. With my best wishes for your welfare believe me dear sir

Your sincere friend

Edward Bunting

Quite apart from the politics of Bunting’s role in the promotion and the killing off of the Irish harp tradition, I think this letter contains a lot of very interesting information. First of all, Bunting’s direct statement that Byrne was “taught to play according to the method of the ancient harpers” not only indicates very forcefully the continuation of the inherited tradition of playing techniques through into the 19th century, but also reminds us that Bunting was active on the Harp Society committee when Byrne was studying at the harp school under Arthur O’Neill in the early 1810s; and Bunting was also on the selection committee for the second school when Patrick Byrne presented himself as a candidate at the Harp Society House on Cromac Street, on Monday 21 Feb 1820. We also see Bunting drawing explicit parallels between Byrne’s playing, and the playing of the 18th century harpers who Bunting had sat with and transcribed live from in the 1790s, when he comments on how Byrne would “stop the vibrations of the strings”.

The Packet article in mid-May says Byrne intended to stay in Dublin for “the next fortnight”, so perhaps he left Dublin at the beginning of June, or perhaps he stayed longer in Dublin than he had planned. Either way, he was back in Warwickshire by the end of July. He had been in Ireland for a year and a half, from January 1839 until June or July 1840.

Back in England, summer 1840

IRISH MUSIC. – The genuine lovers of Erin’s ancient minstrelsy, not less than the friends to whom his social virtues have endeared him, will be glad to hear that Mr. PATRICK BYRNE, the Blind Irish Harper, has returned to his old quarters – The Royal Hotel. During his absence from Leamington, for a space of nearly two years, Mr. Byrne has made a tour through his native land, where, we are happy to hear, he has been gaining “golden opinions from all sorts of men.” Few persons are better acquainted with the legendary lore of his country; a circumstance which materially assists him in giving proper effect to music, the character of which fills the mind with delicious fancies. We are scarcely saying too much when we state, that Mr. Byrne belongs to a race, which, we fear, will die with him; and, like him, we are tempted to exclaim –

“Where are the heroes that lived of old

Who, sleepless, listen to their songs?

Open your hall, – Ossian and Dalo;

By night the bard is no more.But, oh! before my shade depart

Leamington Spa Courier Sat 1 Aug 1840 p2

To the final abode of bards on high,

Give me once more my harp and shell,

Then, loved harp and shell, adieu!”

The poem is a new “translation” published in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, Feb 1840 p.175, so I doubt that Byrne himself sung it.

I don’t have anything for the rest of 1840, so I don’t know what Patrick Byrne was doing, where he was staying, who he was meeting. In September 1840, the Chambers Edinburgh Journal printed its extended review of Edward Bunting’s Ancient Music of Ireland, including the description of Byrne (no. 451, Sat 19 Sep 1840, p279, transcribed above). The whole thing was reprinted in the Roscommon and Leitrim Gazette Sat 17 Oct 1840 p4. But this is retrospective and doesn’t tell us anything about what Byrne himself was up to at that time. Perhaps one of his friends or hosts read the review out loud to him. Or perhaps not, since neither of these titles would have been circulating in England.

My guess at this stage is that Byrne spent the second half of 1840 in England, working for his patrons there, networking, making connections with the top aristocrats, and finally getting the Royal Summons. He went to London to visit the Queen in January 1841. But we will talk about that in Part 4.

Edit 4th December 2023: I have written part 4 of this series.

I updated my map to show the new patrons and places we have mentioned in this post.

Header image: Portrait of Patrick Byrne, from National Galleries Scotland CC-BY-NC

Thank you, Simon!

This quote you include from Rev. Dr Paterson is really interesting. I have long been wondering if the harpers who played with their fingertips developed hard callouses on the tips.

“…We have a Blind Irish Harper here at present, the tips of whose fingers are hard as horns with touching the strings of his harp, who is taking lessons from Mr. Gall in reading, and getting on amazingly well…”

Thanks Karen. I think it varies from person to person, and of course how much they play. I don’t get calluses as such. Maybe Byrne had a certain type of skin; maybe he played for hours each day.

I think “hard as horns” is exaggeration – if you re-read the entire report there is a subtext of some kind of argument that even the “working blind” with tough work-hardened fingers are well able to learn to read using Gall’s system of embossed letters. I think this was part of a kind of propaganda war between the inventors of different lettering systems. Braille of course won, though Moon seems to have had a good case too.

I found it fascinating that fact Patrick Byrne is reported people taught in Irish with names for the various strokes. It very much supports the current work being explored. As well the mention of the octaves being the servants to the sisters.

“Since hearing from you, I have learned from Pat Byrne, a Harper, that all Harpers prior to O Neill, having taught only through the medium of Irish, must have had names for all the strokes, or Chords on the harp – The strings which are octaves to the Sisters he said had others which were called “Gilli ni fregragh ni Haulai” the servants of the answers to the sisters – “