I was very pleased to discover what seems to be a traditional sung version of a Carolan song.

I first read about the singer Máire Ní Arbhasaigh (Mary Harvey or Harvessy) (1856–1947), from Clonalig, near Crossmaglen, County Armagh, in Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin’s book, A Hidden Ulster (2003), p.391-2. Pádraigín explains there how Mary had made audio recordings in 1931. I first heard one of the recordings on Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin’s web research article, Carolan in Oriel, where Pádraigín includes the audio of Mary speaking or reciting 10 lines of Carolan’s song-poem in praise of Caitríona ní Mhórdha (Catherine O’Moore). I subsequently followed Pádraigín’s references and found more information about the recording, and a number of slightly varying transcriptions of the song words, in Róise Ní Bhaoill, Ulster Gaelic voices: bailiúchán Doegen 1931 (Belfast, 2010), p.332-3, and on the Royal Irish Academy’s Doegen Records Web Project, and also on Ciarán Ó Duibhín’s web pages.

In September 1931, Karl Tempel was in Belfast making audio recordings of Irish-speakers. Tempel was working as an assistant for Dr Wilhelm Doegen (1877-1967), Director of the Lautabteilung, Preussische Staatsbibliothek (the Sound Department at the Prussian State Library), Berlin. The project was organised by the Irish state, to gather samples of spoken Irish from different regional dialects. The Belfast sessions brought speakers from counties Antrim, Derry, Tyrone, Armagh, Cavan and Louth up to Queen’s University, where they spoke into recording machines. The wax originals were sent back to Berlin, where they were transferred on to shellac discs, which were lodged with different institutions in Ireland.

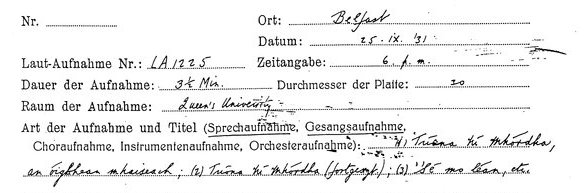

Máire Ní Arbhasaigh was the only person from County Armagh to go to Queen’s to be recorded. She made two single-sided records on 25th September 1931; each record was accompanied by a sheet of personal information. Record LA 1224 was made at 5:30pm, and record LA 1225 was made at 6pm. The indexes list the contents of each record by the first line of the poem or words spoken. It’s not clear to me how or why the tracks are separated on the discs. Were the three tracks made as a single take, and separated by Tempel? Were they separated in Berlin? Or were they done as three separate takes one after the other?

LA 1224 contains three tracks; the first two are two sung extracts from the famous song Úirchill an Chreagáin (part 2), and the third track is a spoken version of the words of another song, Aige bruach Dhún Réimhe. Both these songs were composed by Art Mac Cumhaigh (1738-1773), who Mary claimed to have been related to.

The second disk, LA 1225, contains four tracks. They are listed in the online archive as the sung version of an otherwise unknown song, Tá mé buartha, the spoken words of the Carolan song (Seabhac na hÉirne), Caitríona Ní Mhóra, an óigbhean mhaiseach, the spoken words of another song sometimes associated with Carolan, (Kitty Tyrrell) Sé mo léan go bhfacha mé (although she starts to sing this one, but switches to monotone speaking after the first line), and then the sequence of numbers from 1 to 20.

Pádraigín explains that Doegen and Tempel were “generally more interested in recording the spoken word, and did not usually encourage singers to sing, but rather to recite the song” (Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin, Carolan in Oriel)

I was listening to the first track on LA 1225, the song “Tá mé buartha…” and I kept thinking I should recognise the tune. It took me a wee while to realise it is the tune of Seabhac na hÉirne, or the Hawk of Ballyshannon, Carolan’s praise song for Catherine O’Moore (DOSC 134).

The first and second track of LA 1225 are not independent song texts. They follow straight on from one another, and form a sung part and a spoken part of the same song. The original handwritten record sheets confirm this, listing disk LA 1225 as containing “(1) Tríona ní Mhórdha, an óigbhean mhaiseach; (2) Tríona ní Mhórdha (fortgesetzt); (3) ‘sé mo léan, etc.” (fortgesetzt means continued)

[sung]

- Tá mé buartha tréanlag claoite

I am perturbed, thoroughly weak - fá rún mo chléib, Is níl mo leigheas insa tír

and subdued by my dearest love, And nothing in the land will cure me - amar bhfaighidh mé do póg Rachaidh mé faoi fhód,

if I don’t receive your kiss, I will go to the grave; - chuala mé, a stór, gur chlaon tú,

I heard, my dear, that you refused, - A Dhia gan tú agam in mo líontaí,

Oh God, without you in my clutches, - is mé a fháil bás de do ghrá (…) (sínte),

and I am dying of your love (…) lying down (?), - Dar a labhraim le mo bhéal is tabhair leigheas ar mo chéill,

By all I say, and cure me of my disease (?), - Ó, is cha déanfainn do mhalairt achoíche.

Oh, and I would never replace you.”

[spoken]

- Ó, a Chaitríona Ní Mhórdha an óigbhean maiseach

Oh, Catherine O’Moore, the lovely young woman, - a thug barr deise ar Venus

who surpassed Venus in beauty, - ‘s í seo an cúilfhionn mhúinte bhéasach,

she is the fair one of good grace and deportment, - a gile gan smúid a fuair clú ban Éireann,

bright without stain, famed above women of Ireland - an fhaoileann óg is milse póg.

The fair maiden whose kisses are sweetest - Is gur Caitríona Ní Mhórdha a tráchtfaí,

It is to Catherine O’Moore they would refer - in ainm na mbruigh-bhan láidir,

in the name of the strong fairy-fort women - is minic a thug cíos ins an áit seo;

who have often paid their due in this place - ó, an lon dubh an t-éan atá gnaíúil daite,

Oh the blackbird is a pretty coloured bird - is é siúd atá mé a ráitigh.

It knows that it’s to her I’m referring

Image, audio, text and translation © 2009 Royal Irish Academy, used under Creative Commons BY-NC License.

Carolan’s song

Carolan composed his song-poem on the occasion of the wedding of Catherine O’Moore, to Charles O’Donnell. The poem names her, as O’Moore’s fair daughter, and names him as son of Manus, and Hawk of Erne and of Ballyshannon.

I have been assured by an old Fin-Scealuighe that “O’More’s fair daughter” or “The Hawk of Ballyshannon” was composed for Charles O’Donnell the brother of “Nanny” … This information I find corroborated by accounts derived from the McDermott Roe family

Hardiman Irish Minstrelsy 1831 (vol I p. li)

I have been collating different texts of the song to try and understand how Mary Harvessy’s text fits in here.

Donal O’Sullivan includes Seabhac na hÉirne in his Carolan as no. 134, and he lists sources for the text. I have also tried to find other sources.

The earliest text I have found was collected from a traditional singer in County Mayo in 1802, by Patrick Lynch. You can see Lynch’s three verses in his manuscript copy book at Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.10.115-116.

In 1829, Thady Connellan published two independent texts of the song in his Duanaire Fonna Seanma. On pages 11-12 is a long version of the song, with 9 verses. Donal O’Sullivan printed the text and his own translation of the first two of these verses in his Bunting 1983.

On page 44 of Duanaire Fonna Seanma, Connellan prints two verses of the song along with a metrical English translation written in Irish orthography.

There is a version with three stanzas printed along with a melody, in Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society, vol. VII p.21. The caption says “collected by Capt. Ricky of Mount Hall, Killygordon, Donegal.” However the text seems to be the same as Lynch’s , and Charlotte Milligan Fox who was editor had Lynch’s manuscript at that time, so it seems likely that only the melody was collected by Ricky. Fox also gives an English translation.

Tomás Ó Máille prints a version of 8 verses in Amhráin Chearbhalláin (1916), p.135-8, no.23, Seabhac bhéal átha seanaidh, assembled from different 19th century manuscripts. Two of the verses he gives seem to be variants of each other.

We can see that lines 13 to 18 of Mary Harvessey’s text match lines 3 to 8 of the first verse given by both Lynch and Connellan; Ó Máille also has this verse later in his edition. Here is Lynch’s text, with Milligan Fox’s translation:

- Ag so feairin deagh mna aílle

Behold here a gift of female beauty - O Chonchubhuir O Reighlligh go sleibhte I mhaille

From Connor O’Reilly to the mountains of O’Maily - An rioghuin og is milsi póg

A young lady of the sweetest kiss - Sar inghin I mhordha a tractaim

I speak of O’Moore’s fair daughter - Siur na righ bfear laidir

Sprung from princely heroes - as minic chuir ciosa ar naimhde

who often laid their enemies under tribute - Phlanda an tseain sna ceraobh folt taite

You prospering plant with delightful branches - Is tusa ta me raidhte

it is thyself I speak of

The beginning of Mary Harvessey’s spoken section (lines 9-12 of her text) is harder to place. There is a couplet in Connellan’s and O’Máille’s texts which refer to Venus or Deirdre. Connellan has

- Súil mar dhruacht an tsamhraidh,

- Cosamhuil le Deirdridhe a dealradh,

O’Maille has this verse in two different forms,

- A súil mar dhrúcht ré dealradh,

- Cosmhail í lé naomh as Párthar

and

- Thug rí bárr sgéim air mhnáibh na cruinne

- Ó Venus as ó Dhéirdre

Mary’s sung text is the hardest to reconcile with any of the other versions though. It seems to be slightly different in tone, directly addressed to the woman by a rejected lover. Mary’s lines 3 and 4 are vaguely reminiscent of lines in a verse given by Lynch and Ó Máille. Again, here is Lynch’s text and Fox’s (slightly corrupt) translation:

- Racha me san uaidh

I shall descend into the grave, - Se is dual dom aicid

It is due to my comp - Ma ngluaiser seal mbiomsa.

If you do not hasten shortly to where I am

Lynch’s text seems defective here, with 14 and 15 appearing to be one line broken over two. Ó Máillie has

- Rachad insa n-uaigh mar budh dúal do m’aicme,

- mur dtige tú seal go dtí mé.

Not very similar at all really! And this is the closest couplet I can see.

However, I don’t think this is necessarily a problem. In the two hundred plus years of oral transmission from the wedding of Catherine and Charles, we might expect words to be swapped out, verses to change order, and entire couplets or verses from metrically similar songs to be inserted. That is part of the living song tradition. Of course Mary was not singing the exact same words which Carolan sang at the wedding two centuries earlier, but no-one would expect her to be.

Incidentally, I find it interesting that Mary’s text is the only one which names Catherine. Everywhere else she is only referred to as the daughter of O’Moore.

Carolan’s tune

We can check my Carolan Tune Collation spreadsheet to see how the melody has been transmitted. There are a number of printed and manuscript settings of the tune from 18th century classical musicians.

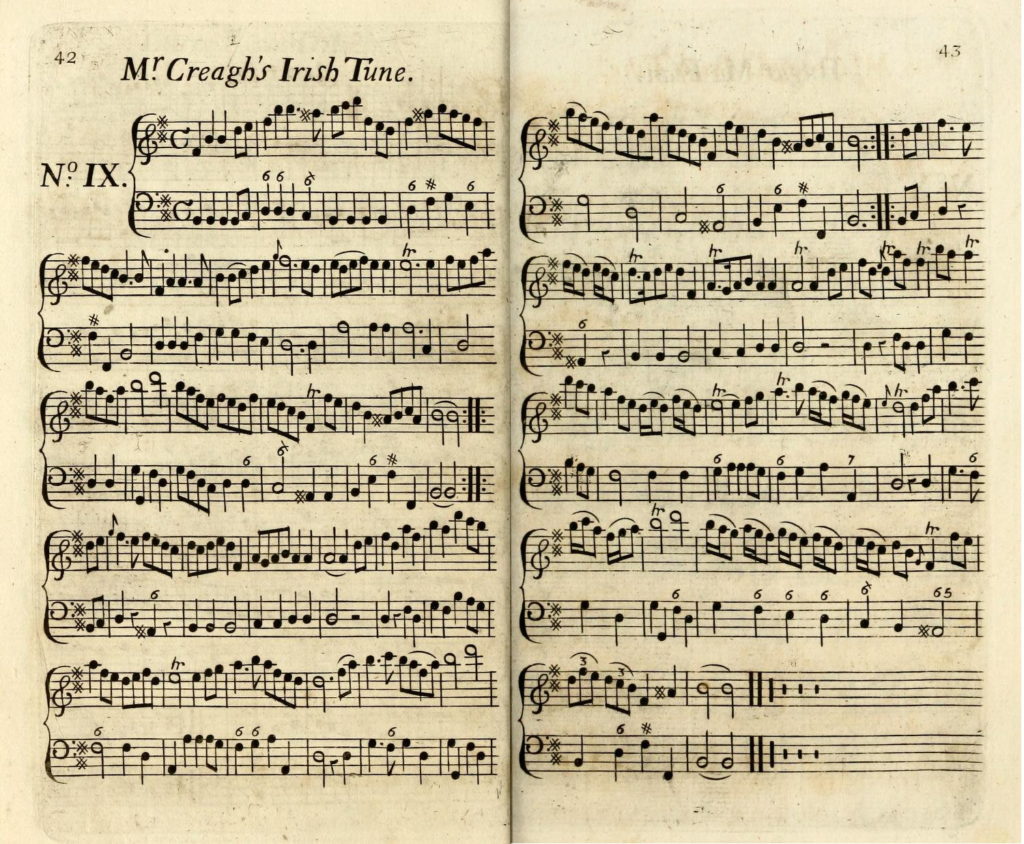

Perhaps the earliest version of the tune was published in Burk Thumoth’s Twelve Scots and Twelve Irish Airs (no. IX, p.42-43) in c.1742-5. The tune is titled “Mr. Creagh’s Irish Tune” and is in Thumoth’s usual format, of an arrangement for harpsichord, or for violin or flute with figured bass. Thumoth also gives his usual over-elaborate variation on the facing page.

I don’t know who Mr. Creagh was. Burk Thumoth’s titles are often way off beam, like he heard them third hand and didn’t understand them and wrote them all wrong.

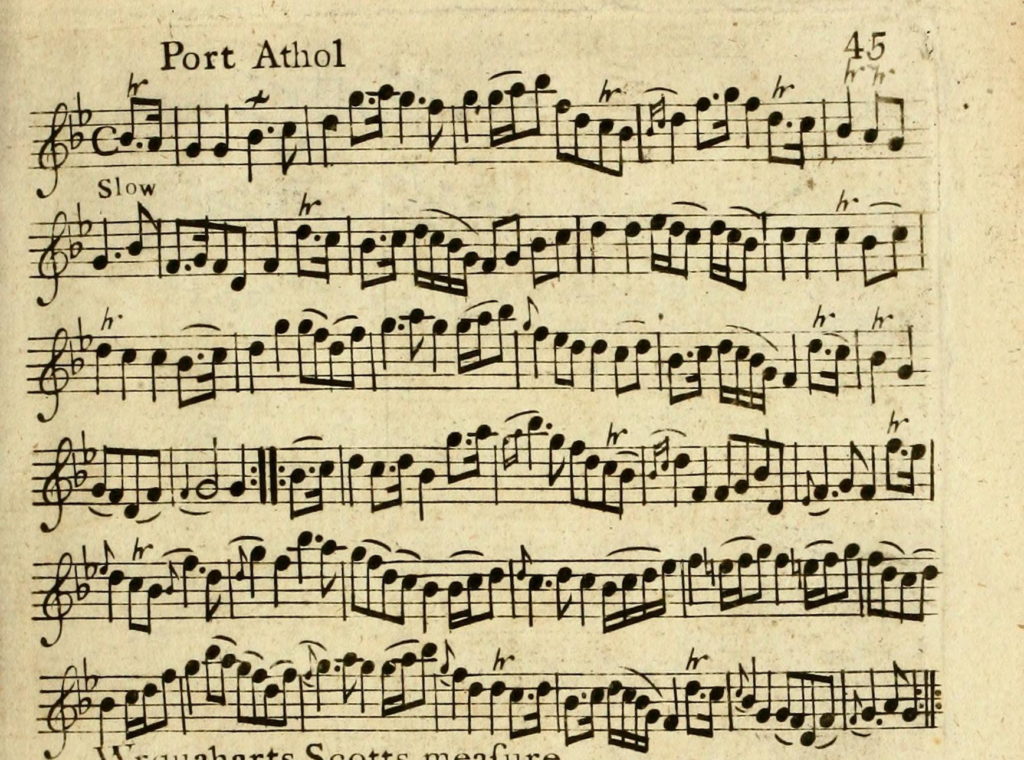

Our tune appears a little later in the Caledonian Pocket Companion (book 8 p.45). John Purser in the introduction to his CD-ROM edition (p.4) implies that Book 8 may have been published c. 1757-60.

As is usual with Oswald’s editions, this is a baroque violin or flute re-working of the basic tune. The title, Port Atholl, is very interesting, and links in with the tradition reported from the old Irish harpers in the 1790s, that the tune was not originally composed by Carolan, but is Ruaidrí Dall Ó Catháin‘s Port Atholl. We can also check my Rory Dall Tune List PDF to see other appearances of the tune. This is not the place to go into the question of whether this tune actually goes back to Rory Dall. There are two tunes called Port Atholl, and this is one of them. I mention this question on my page about the other one.

In Lee, our tune is called Mrs. O’Donnell, clearly referring to Carolan’s wedding song. I don’t know Lee’s source for the tune; he gathers tunes from all kinds of previous written sources including from John Carolan’s book of his father’s compositions. Anyway, Lee’s harpsichord setting of Mrs O’Donnell looks, frankly, corrupt.

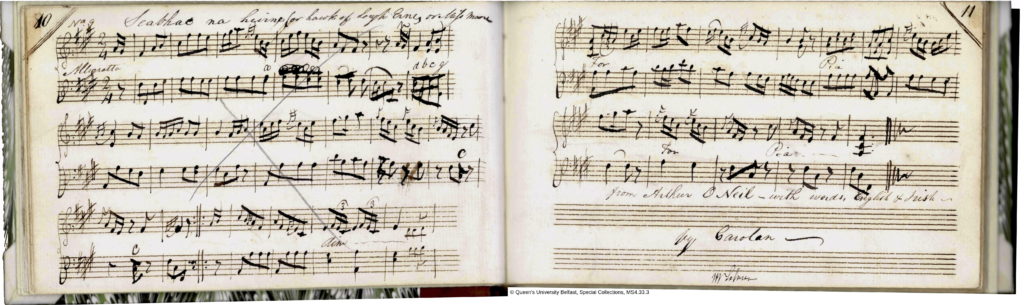

Edward Bunting has a version of our tune in his 1798 unpublished piano book, Ancient and Modern Irish Music (not published)… where it is titled “Seabhac na hEirne or hawk of Lough Erne or Miss Moore / from Arthur O Neill with words English and Irish / By Carolan”.

Unfortunately I have not yet found a live transcription from a harper or singer in Bunting’s field notebooks, so all we have are his piano arrangements. It is an open question as to how much of this 1798 piano arrangement represents Arthur O’Neill’s playing on the harp, or indeed his singing, or how much is Bunting’s piano invention. It is even possible that Bunting made this piano version primarily by reference to the earlier published scores, and merely added the “Arthur O’Neill” tag to indicate that O’Neill had played it or given lore about it.

When Bunting came to publish the tune in 1840, he did give some traditionary information about the tune, perhaps from Arthur O’Neill. Bunting tells us

(No. 13 in the Collection) Seabhac na h-Eirnè. “The Hawk of Ballyshannon”, or “O’Moore’s Daughter”; an altered composition of Rory Dall, being his “Port Atholl” somewhat varied by Carolan, who composed words to it for Miss Moore. It was uniformly attributed to its proper composer by the harpers at Belfast.

Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland, 1840 introduction p.91

After that we get more and more notated versions, not all of which I have seen. Many of these are derived from Bunting’s published piano arrangement.

All of the tunes we have looked at so far have the same form, with two eight-line halves. If we were to try and sing Carolan’s lyrics to any of these tunes, we would need two verses to fill the tune. However, some of these classical settings (including Bunting’s 1798 piano arrangement) put repeat marks in between the two halves.

Traditional versions of the tune

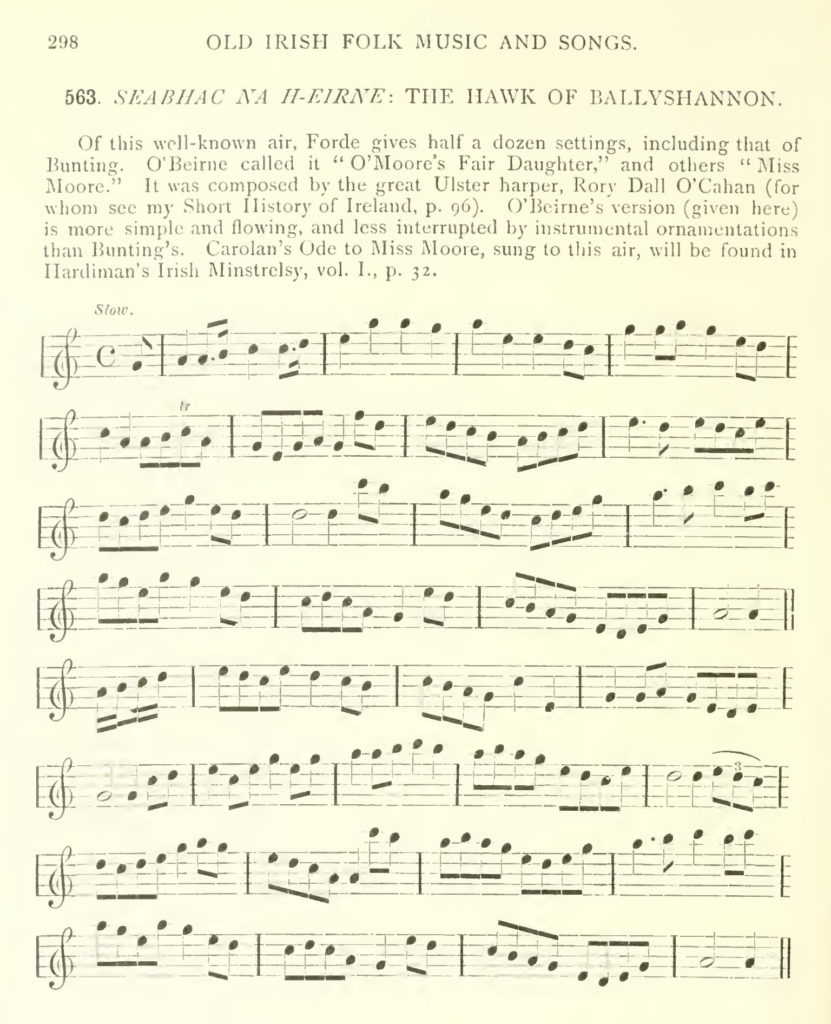

In my Carolan Tune Collation spreadsheet I have not paid much attention to 19th and 20th century traditional instrumental versions of Carolan’s tunes, since I was there focussing on trying to identify and collate traditional old Irish harp settings where they survive. But we don’t have a traditional harp setting of this tune – we don’t have a live transcription from an old harper in Bunting’s manuscripts. So perhaps we should look at some of the traditional instrumental versions of the tune. Below is the version “taken down by Forde, in 1846, from the playing of Hugh O’Beirne, a professional fiddler of Ballinamore, Co. Leitrim” (Joyce p.296), and published by Joyce in Old Irish Folk Music and Song, (1909), p.298

O’Beirne’s traditional fiddle setting follows the same general pattern as the classical instrumental arrangements discussed before, having two halves each of 16 lines (though without a repeat mark in the middle). There are other traditional settings listed by Donal O’Sullivan (Carolan vol 2 p.83) which I have not tracked down yet. O’Sullivan mentions a setting taken down by Forde from a piper, Patrick Carey of County Cork, which is titled “Port Atholl”.

Song-air versions of the tune

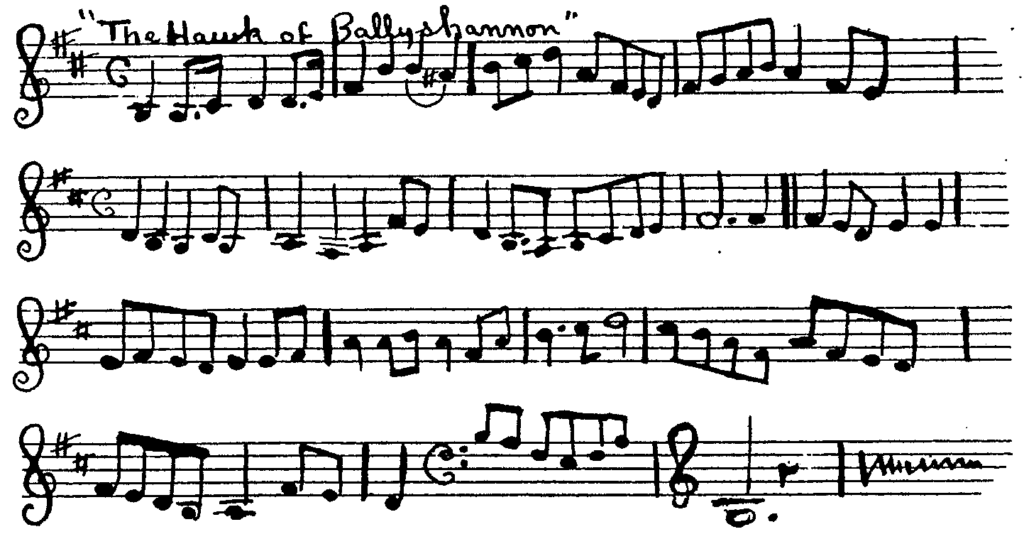

There is one printed tune I know of which derives from traditional sung performance, and interestingly, just like Mary Harvessey’s recording, it only gives the first half of the tune. This is the same page in the Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society, vol. VII p.21 which gives Patrick Lynch’s text and Charlotte Milligan Fox’s translation which I referred to above.

This version was collected by Capt. Ricky, of Mount Hall, Killygordon, Donegal. He states the air was known and sung by different members of his family. The air was composed by the great harper, Rory dall O’Cahan. Carolan wrote an ode to Miss Moore, and it was set to O’Cahan’s air, and known as “O’Moore’s Fair Daughter”. For other versions see Dr. Joyce’s “Old Irish Folk Music and Songs”, page 298, and Edward Bunting’s 3rd Vol. Bunting took down his version from the harper, O’Neill, in 1792. C.M.F

Journal of the Irish Folk Song Society, vol. VII p.21

In comparison to Mary Harvessy’s tune, this version shows classical touches – the sharp 7th at the end of bar 2 especially, but also the way it fills in the gaps in the pentatonic scale. Mary’s tune, by contrast, is perfectly in the pentatonic minor mode, in that she studiously avoids the gaps in the scale (2nd and 6th). Her intonation is very wayward though – she starts with almost a major 3rd which shrinks each time she sings it towards the minor 3rd.

Future work

My Catherine O Moore Song Text Collation spreadsheet tries to line up matching verses from different versions of the text, including Mary Harvessey’s. There are more texts we could consult, to try and get a clearer picture.

I need to listen more to the recording, to understand how the tune curls. I should learn the words. We need to consider the implications of this for giving us an insight into a potential style to look towards in playing Carolan tunes and song airs on old Irish harp.

Most of the versions of this tune which we pay attention to, have come through the classical tradition. I assume the present day oral tradition versions of this tune mostly derive from Donal O’Sullivan’s 1958 edition, which is “slightly altered” from Edward Bunting’s 1798 piano arrangement. I think a proper study of non-classical sources of this tune as represented in the 19th century collections from fiddlers and pipers, would be a very useful contrast to the study of the 18th century classical settings.

We need to look for more relevant traditional music and song performances and recordings of other old Irish harp tunes, which could usefully inform our understanding of the old Irish harp repertory and traditions. My Old Irish Harp Transcriptions Project has been seeking out notated traditional old Irish harp performance versions of tunes, but there are many tunes which we don’t have these live transcriptions for, like with this one; and even when we do have a live field transcription, it could be useful to be able to compare it to other traditional performances of the same tune.

We need to think hard about the old Irish harp tradition, style, and idiom. Where do we want to situate old Irish harp performance? Do we want to be closer to Burk Thumoth on the harpsichord? Edward Bunting on the piano? To Hugh O’Beirne on the fiddle? To Máire Ní Arbhasaigh singing? These are political questions about the worlds we want our music to live in.

Header image: Creggan River above the Liscalgot Road bridge, cc-by-sa/2.0 – © Eric Jones – geograph.org.uk/p/5920147

You can see the Broderip & Wilkinson unauthorised reprint of the Lee Carolan book, online at https://archive.org/details/hartley00581081/page/n339/mode/2up/

Mrs O’Donnell is no.38 in this book (the tunes are not titled)