I was very pleased to discover what seems to be a traditional sung version of a Carolan song.

Continue reading Seabhac na hÉirne, or the Hawk of BallyshannonTag: archive recordings

Irish Terms

I transcoded the audio and video on the Irish Terms page. Hopefully they will now work no problem on modern computers and browsers. Next, the videos need updated and the whole look of these pages. Later…

Check it out at http://earlygaelicharp.info/Irish_Terms/

Teresa McCormac of Dublin

I found a shellac 78 disc of Irish harp played by Treasa Ní Chormaic. I don’t know the date of this disc.

Update Jan 2018: Bill Dean-Myatt says it was recorded circa September 1930

I have transferred both sides onto mp3 for you, using a modern turntable.

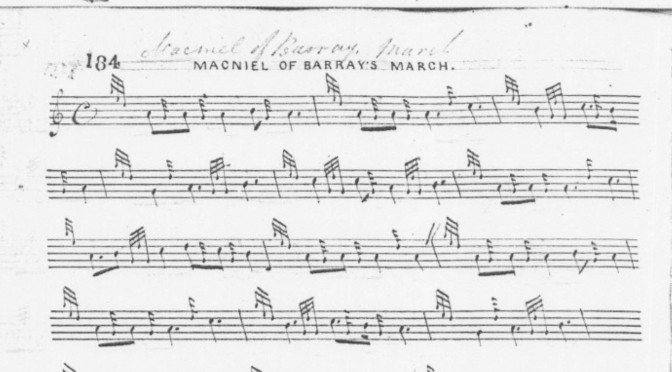

MacNeil of Barra’s March

I am going to play the replica Queen Mary harp in Kisimul Castle on Barra in the Autumn, and so I thought I should get a MacNeil of Barra tune up and running. I am finding it a great challenge to get MacNeil of Barra’s March working on the harp.

Archie Anderson, scots songs

The most popular record at yesterday’s Wighton Centre event was the 1914 disc of Archie Anderson singing Scots songs with a wind-band accompaniment. Some of the Scots Song group who meet weekly in the Wighton Centre were there, and they of course knew the songs and so were very interested to hear this 100 year old recording being played on the antique wind-up machine.

I played his recording of “Jock o’ Hazeldean”, a traditional border ballad re-written by Water Scott, as part of the half hour event. At the end, Sheena Wellington acting as host suggested there would be time for an extra disc before everyone had to leave, so I asked if anyone had any requests, suggesting perhaps a second side of one of the discs we had heard. Archie Anderson’s record was the one called for, so I played the other side, “The Bonnie Lass of Ballochmyle”, a song by Robert Burns.

When I got home yesterday evening I played them both for you to hear as well! I hope you enjoy listening:

Reading about historic recordings

When I suggested to the committee of the Friends of Wighton back in the spring, that I could do a gramophone session for one of the regular Wednesday lunchtime concerts in the Wighton Centre in Dundee, I just thought it would be a bit of light-hearted fun, but actually it has become quite a serious task for me! From planning the sides and running order I’ll play, to opening and cleaning and oiling the machine, to reading up on the music so as to have something useful to say during the presentation, it is taking up a lot more time than I expected.

I have been reading some interesting books or at least sections of books. In Scottish Life and Society, A Compendium of Scottish Ethnology, volume 10: Oral Literature and Performance Culture edited by John Beech, Owen Hand, Fiona MacDonald, Mark A. Mulhern and Jeremy Weston, (John Donald in association with the European Ethnological Research Centre and National Museums Scotland, 2007) (phew!), there is a very good chapter by Stuart Eydmann, ‘Diversity and diversification in Scottish music’. Eydman gives as a subtitle ‘Sketches for a Scottish musical-historical map’, and then gives a couple of pages in turn to a half-century or so, starting with “before 1840”, and then progressing, “1840-1900”, “1900-1945” and “post 1945”.

Of course it is the “1900 to 1945” section that is most relevant to the Scottish 78rpm gramophone records, though the late 19th century observations are useful as well. Eydman deals clearly and concisely with the different types of musical activities which different parts of society took part in, including domestic performance on instruments, both working class and ‘bourgeois’, as well as the music hall, one of the most important contexts for the gramophone records.

It seems to me that there were two different backgrounds from which musicians would come forward to produce a gramophone record of “Scottish music” in the teens, twenties and thirties: music hall performers, and “concert artists”, i.e. classical musicians. Harry Lauder is of course the best known music hall artist performing “scots songs”, and on the disc of his I have he is very much playing up all of the negative racial slurs of the Scotsman as a foolish, drunken, untrustworthy figure of fun. Both on this disc and on another, a record of Jock Mills from 1914, there is a similar vocal style, with slighty hysterical-sounding swoops down onto certain stressed notes, and a very curious extended rolled R in the middle or end of many words – I’m not aware of this sound as a part of any Scottish dialect and I assume it is a music-hall comic convention.

Marjory Kennedy-Fraser is the best known “concert artist” in this field. Her “Songs of the Hebrides”, ostensibly arrangements of traditional Gaelic songs, but in reality pretty much newly-composed pastiches, were very popular, and many classical singers specialised in them, such as Joseph Hislop (I have a 1933 disc of him). But other classical musicians turned to what we would consider genuine traditional material, and performed it in a pretty interesting straight classical style, such as Archie Anderson singing “Jock O’Hazeldean” (Walter Scott’s tidying up of a traditional border ballad) in 1914, or Kenneth MacRae singing “Òran Mòr Mhic Leoid” (a Gaelic song composed in the 1690s by Rory Dall Morrison) in 1931. The text is straight, the accompaniment is simple, and the vocal style is the classical norm of its time.

David McCallum was a leading violinist with the Edinburgh symphony orchestras, and you can hear his classical learning on his record (c.1929) with its extensive slow portamento sliding, but he has a lot of very distinctive Scottish fiddle ornaments as well – this is not just a straight classical performance of the tune, such as we hear today from players like Jordi Savall. McCallum very much has a foot in both camps. I almost said if indeed there were two camps then but of course there were, and we can hear the other “traditional” style on the archive recordings. But the old traditional fiddlers would never have made a gramophone record in the 1920s or 30s!

John MacDonald of Inverness on the pipes, playing “Lament for the Children” in 1927, does fit into this model, but perhaps not as obviously as first seems. Obviously he is not a “music hall performer” or indeed a “concert artist” in the classical sense, but his playing style, and the Pìobaireachd Society score he is working from, represent the height of high modernism, to the point that the traditional tune is barely identifiable in his extremely mannered playing.

The use of sliding as an articulation in classical music is a fascinating aspect of performance practice that is almost completely lost today. Robert Philip’s book Performing music in the age of recording (Yale 2004) documents in huge but fascinating detail the changes in performance style which were brought about in the 20s and 30s by the development of recording technology. This book reminds me of why I love the late 20s recordings so much – they are after the invention of electrical recording in 1925, so the sound quality is much better than pre-1925

records, but they are before the big changes in style and presentation which quality recordings drove forward.

I also read Susan Motherway’s paper ‘Mediated music? the impact of recording on Irish traditional song performance’ in the interesting collection Ancestral imprints: Histories of Irish traditional music and dance ed. Thérèse Smith (Cork 2012). Apart from the rather silly pomo writing style of the title and introductary paragraphs, this is a very insightful article that considers commercial recordings of traditional singers from the 1990s on. Apart from the good comments about the way in which different recordings place themselves very differently in the market, I was most struck by the comments about the amount of control that recording and sound engineers now have over the sound and the music of the singers.

It almost seemed reading this article that similar issues dealt with by Phillips for classical music in the 1920s and 30s, are currently playing out in traditional music. Perhaps these things are always playing out to some extent, but I am fascinated by that constant tension between the musician as a performance artist, standing in front of or even better alongside an audience of their peers, and presenting a musical performance as a personal interaction, saying something to the listeners; and the recording as a product, a manufactured good, that is to be kept on a shelf and admired as an artefact.

Scottish music 78s

I have been getting my records out, ready for next Wednesday’s event in the Wighton Centre, Dundee. I am getting nervous now, whether the machine will behave itself, and whether it will all run to time OK! I have about half an hour, and so I was thinking that perhaps 6 sides would be OK, though I do think I may overrun if I chat about each track! But I do want to include Gaelic song, Scots song, fiddle, pipes and clarsach, so that’s 5 sides instantly, and I have to play the disc with Marjory Kennedy-fraser at the piano. So we’ll see.

I am thinking I might also take along some of my other discs just to show off or for people to look at (and perhaps for requests after the event is over!). I have another 1914 “Scots song” disc, the Joseph Hislop disc, and one Jimmy Shand (from the ’40s I suppose) and one Harry Lauder which looks like it is from the teens. It’s not a huge collection but it is pretty diverse representation of Scottish music.

I thought of also taking the Mabel Dolmetsch discs to show as well, but they are just too fragile to risk travelling with and they can’t be played so I think there is no point.

You can get the full description of the event next Wednesday lunchtime on the Friends of Wighton news page.

I am tired and alone

I am wearied ma lane, pu’in breckens early. Tha mi sgith ’s mi leam fhìn, buain na rainich, daonnan. Cùl an tomain, bràigh an tomain, an tomain bhoidhich; h-uile la n’am onar.

I am tired, I am alone, pulling bracken, all the time. The back of the hill, the side of the hill. The pretty hill; every day I am alone.

I learned this song from archive recordings of William Matheson in 1976 and also Belle Stewart in 1979

This is a song we have been working on at my harp class in Dundee.

Scottish 78s

In six months time I have agreed to present a rather different programme for the Friends of Wighton – half an hour of ’20s sounds from old Scottish 78rpm gramophone records. It will be Wednesday 1st October, 1.15pm, in the Wighton Centre, Dundee Central Library.

I realised that I have plenty enough discs for half an hour – just one side of each from a selection will be more than enough. We will have Gaelic song, Scots song, fiddle, pipes and clarsach; the oldest disc is from about 1914 and the most recent from 1931.

I was also thinking about the dates and provenances of the various discs. The one shown above was recorded in London, though I assume it was made for the Scottish market. I have what I think is the oldest Scottish harp record, that is Patuffa Kennedy Fraser’s disc of “Songs of the Hebrides” from 1929. I also have what seems to be the oldest Irish harp record, Mabel Dolmetsch’s “Victorious tree”, recorded in 1937 though never released (I won’t be playing this one as it is too fragile as well as not being Scottish!)

Mabel’s record is Irish harp music but she wasn’t Irish or living in Ireland, so I wondered what was the oldest Irish harp record? Was Mabel first? Actually it seems she was. Susan Reed appears to have been the next to record, and her “Old English Folk Songs” released in 1945 would be the earliest published recording of Irish harp, even though the performer is American and the repertory is English! Mary O’Hara put out her first disc in 1956 I think. I’m having trouble tracking down other Irish harpists on record from this era.

Eskimo violin / Inuit fiddle / Tautirut

I have finally acquired a copy of archive recording of tautirut playing from 1958 held by the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec.

Tautirut is the Inuit word for the bowed harp or box zither played in the area around northern Quebec and southern Baffin Island. It has strong connections to other bowed-harp traditions in Scandinavia and further afield. For more on the wider bowed-harp and bowed-lyre traditions I have made a bowed-harp web page.

The collector Asen Balikci was visiting Povungnituk in Quebec in 1958, and he seems to have commissioned the people there to make a couple of “reconstructions” of the tautirut. I assume the “reconstructions” were necessary because the tradition was moribund there by that date.

Cariola, then 38 years old, played tunes on the newly made instruments. Balikci recorded her playing and took the instruments and the tape recordings back to the Museum.

The instruments are similar to each other; each has three sinew strings. The bow is strung with a willow root. They have only one bridge, so the strings must be fingered where they come off the soundboard, not into the air as on the Icelandic Fiðla and earlier Tautirut.

Here are the catalogue entries for the two instruments:

IV-B-648 made by Peterussie

IV-B-649 made by Krenoourak

Krenoourak’s instrument looks better; it is longer (though still not as long and slender in shape as the late 19th and early 20th century instruments), and it includes two little bits of wood which are now separate but which I presume are connected to tuning the instrument. These things have no tuning pegs; the strings are just attached to the ends, or in Krenoourak’s case, to leather straps attached to the end. Peterussie’s instrument is extremely short and fat, but it does have an ivory nut at each end where the strings pass over the ends.

Here is the museum catalogue entry for the sound recording:

Control no. IV-B-46T

Cariola’s playing is very interesting, fast and obviously improvised. She uses different tunings; in the earlier tracks she has the instrument tuned with the drone a 4th below the melody note; in later tracks the drone is dropped to an octave below the melody note. I am particularly interested in the track that sounds like a trumpet fanfare, with the melody on 1st, 3rd, half-sharp 4th and 5th of the scale, with the octave bass drone. Her intonation drifts; sometimes it is clean and deliberate, while at other times it is rather wayward.

Her instrument is tuned higher than Sarah Airo’s (see my earlier post) but the general style of playing and the sound is similar. Cariola seems to use the drone more sparingly, touching it at the same time as playing the stressed melody notes, whereas Sarah is more often alternating between the melody and drone strings so the drone becomes a rythmic part of the tune. I wonder about this being a woman’s music, and about the style – it does seem to be connected to other bowed-harp styles from Scandinavia. And the players were 200 miles apart – though perhaps that is not very far in Northern Quebec.

Now to listen and learn some of the motifs and playing techniques!