Edward Bunting made what looks like a live field transcription of a tune titled “Mrs McDermottroe” or “Nanny O Donnely” on p. 18/18/27/f8v of Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections MS4.29. Bunting made an edited neat copy on the facing page, and he published a piano arrangement in his 1797 book (No.53, Anna ni ciarmuda ruaidh / Nanny McDermotroe / Carolan). There don’t appear to be any independent variants of this tune, so the only way to understand it is to analyse Bunting’s very unsatisfactory notations.

Carolan’s patron at Alderford was Mary née FitzGerald (c. 1660-1739), wife of Henry Baccach MacDermot Roe (c. 1645-1715). Their oldest son, Henry (d.1752), married Anne, daughter of Manus O’Donnell of Newport, Co. Mayo, and I assume that this Anne is the person whose name is referred to in Bunting’s manuscript and printed titles: Nanny O’Donnell, whose married name was Anna MacDermot Roe.

Donal O’Sullivan includes this tune in his Carolan and his Bunting; we can use his numbers to refer to this tune (DOSB 53) (DOSC 82). O’Sullivan connects the tune to a song-poem, which seems to be a wedding song addressed to Anna when she married Henry. The song does seem to share meter and structure with the tune, and so I think in this case we can accept Donal O’Sullivan’s suggestion.

There are two independent versions of the the song lyric. One version (QUB SC MS4.10 p. 33/41-34/42) was collected from oral tradition by Patrick Lynch on his tour of Mayo in the summer of 1802. Lynch’s title is “Madam McDermud Roe” and his text reads:

(p.33)

Toig do mhion.. & seol do chiall

mar ordaigeas dia.. dean dreacht is dáin

agus labhuir do mhian… dar an og-mnaoi sgiamhach

do shliucht na Niall.. is riogha fail

brón no tuirse… riamh ni roibh na haice

is fior gur deas. a piob is a leaca

Anna nín Mhánuis… sár mhac Rudhruigh

an ard fhlaith cluiteach.. nach ndiultadh a nglea

Ni breag a dubhairt me fan thrathsa

le geug na lub sna bhfainneadh

gur geaneamhuil a suil.. a déad sa cúl

is leir liom sud.. gur sugach a glóir

Is gurab aoibhin.. don oigfhear críonna

fhantaigh inghion na scoirbhriathar saimh

Ta si momhar caoidheamhuil ceol mhar saoidheamhuil

blath geal deas dílios gach uair is gac am

(p34)

Hanrai mhac searlus se tá me radha

dar dual bheith treigheach ae arach tapuigh

aithnighean a mhion ag an ti da mbiadh se

is eol don tír a ghniomh gur breagh e

da mbiadh fíon an mo laimh se

doluinn fein do shlainte

go mbeannuigh dia an dis se anna & heanrai

lastar a piopa & liontar a dram

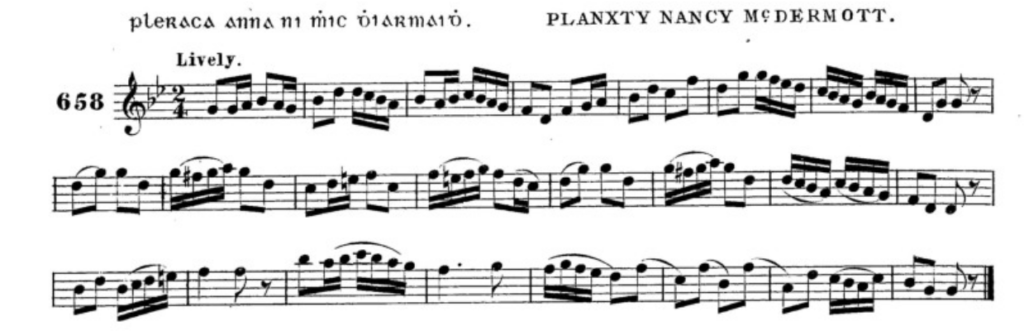

A similar version of six stanzas is printed in Tomás Ó Máille’s Amhráin Chearbhalláin (1916) p.130-131, edited there from two related versions in RIA ms 23A1 and 23I8, which contain poems written down by “Daniel Malone, a schoolmaster,who travelled through the counties of Leitrim, Roscommon, etc., in the years 1827 and 1828 and collected all these songs from the recital of the people” (AC p.46). Ó Máille says (p.289) that “the melody is given by O Neill, Music of Ireland, p,118”. This version seems to be a slightly garbled and slightly more classical adaption of Bunting’s piano setting, with the intrusive f sharps, and the substiution of bars 13 and 14 with material repeated from 9 and 10.

The tune seems to have three sections, each of eight bars; We can suppose that each bar of the tune would take half a line of the poem, so that three verses of the poem would fit the whole tune; the six verses noted by Lynch would fit onto two repetitions of the air.

The main problem with the tune of Anna MacDermot Roe is the key and the accidentals. Bunting’s live field transcription from the tradition-bearer on p.18 is noted at pitch in A minor. In bar 6, the tune seems to pass through F, but the transcription is ambiguous, and the note head is positioned slightly above the line, and could be read as either F or G. In bar 11, the F is clearly noted and is marked with a ♯ in the transcription. There is an f in bar 12, but it is not marked with an accidental – should we assume it is also f♯? In bar 13 there are two fs, as the musical line ascends and descends. Again neither is marked with an accidental. The ascending one is clearly notated, but the descending one is deliberately elongated as if it has been changed from f to g (or from g to f).

In the third section of Bunting’s live transcription, it all goes horribly wrong. Bunting has not inserted bar-lines into the notation after the first two lines, which is often a sign that he no longer believes in what he has written. Bunting starts the third line by apparently transposing his notation down a 4th, so that he writes the first note of this line as g, when we expect it to be c. This is confirmed, as the ascending passage g a b c♯ d shows an accidental sign on the c (we would expect to see c d e f♯ g). After the first two bars, he goes back to notating at pitch in A minor, by writing high c. In the 5th bar of this section, we again have f, without an accidental. In bar 7 the notation comes to a stop.

The fourth line of Bunting’s live transcription represents him trying again to notate the third part of the tune. This time he has transposed his notation down a 5th, so that he starts by writing f, and he writes the ascending sequence f g a b c. He continues to notate the whole of the third section of the tune at this new pitch level. In bar 5, the “questionable note” is now transposed to b, without an accidental mark; but he has also written a note a 3rd lower, g, lined up with the b, as if he was unsure which should be right.

Bunting made a neat copy of the tune on the facing page, p.19. I assume that he wrote this based on the previous live transcription; however it is possible that the two notations were the other way around. We know that Bunting sometimes copied tunes neatly into ms29 from printed books or from other manuscript sources, and he mentions that his collecting tours were at least partly for “comparing the music already procured, with that in possession of harpers”. So, it seems possible that the p.19 neat copy was copied into the little loose-leaf pamphlet out of a printed or manuscript tune-book, and then later when he was out with a tradition-bearer and heard their version, he tried to notate their version on the previous page to capture the differences. I don’t know how likely that is in this case, because the neat copy is very close to the the transcription. At the moment I am working on the assumption that the p.19 neat copy is derived from the p.18 transcription.

The neat copy shows some interesting changes from the transcription. The neat copy is set in D minor, the same as the final line of the transcription. Although there is (as usual) no key- or time-signature, Bunting marks some of the b notes as b♮, implying a key signature of one flat. The 1797 printed piano arrangement follows the ms29 neat copy closely, except the tune is transposed into G minor with two flats; the E is marked natural in the same places as the Bs in the ms29 neat copy, except for bars 12 and 13, where the neat copy doesn’t show accidentals and the piano print does. Are we to assume the naturals in the neat copy?

In any case, this switching between sharpened to flattened 6ths in the minor scale seems to me to be an interesting and curious thing. Is it connected to Bunting’s process of listening to the tunes with a classically-trained piano ear? Can he not help himself but to add in accidentals? Or, is this something that could come from within the Irish oral tradition?

It seems to me that there are three possibilities for reconstructing Anna MacDermot Roe.

- We could consider the transcription as being noted from instrumental harp performance, played on the harp in A minor, with the harp tuned with f♯. All of the fs in the tune would be played sharp, although there are places (bar 6, 13, 21) where we could omit the f♯ and play another note suggested by the transcription (g in bars 6 & 13, d in bar 21). We would pass lightly over the f♯ in bar 21, and we could suppose that Bunting only indicated the ♯ accidental where it struck his classically-trained ear as unusually prominent and distinctive.

- We could consider the transcription as being noted from instrumental harp performance, played on the harp in A minor, with the harp tuned with f♮. All of the fs in the tune would be played natural, and we would explain the ♯ accidentals in the transcription as being inserted by Edward Bunting as part of his editorial process to “correct” or “normalise” the tune for publication.

- We could understand the transcription as being a fair representation of performance, including the sharp and flat 6ths. Obviously this would not be a harp performance, since the old Irish harp does not give the possibility of having sharpened and flattened versions of the same note, and so we can imagine this as a sung performance.

The only metadata we have for the transcription is a tag in the annotated copy of the 1797 printed piano arrangement (London, British Library Add ms 41508, where the tune is tagged “Harp Mooney”, suggesting that the tune was notated from the harp playing of Rose Mooney. These tags were likely written in by Edward Bunting in the early 1840s, almost 50 years after the transcriptions were made, so I don’t know how much weight we can put on them.

If we look at my tune list spreadsheet, we can see that Ann MacDermot Roe is not closely associated with a group of transcriptions. In the previous gathering there are two Carolan tunes that are notated similarly, with dots on the left page and a neat copy on the right page, Planxty Drury and Planxty Kelly. Both are tagged “Byrne” in the annotated 1797, but both are notated one note higher than we expect, which mitigates against Mrs MacDermotroe being associated with them. There are other “mixed pitch level” tunes in the same gathering and after Anna MacDermot Roe, and there is also the Rambling Boy which is later tagged Charles Byrne, and which appears to be a vocal setting.

Charles Byrne was not a very good harper, but he was praised for his singing and Bunting says he got a lot of songs from him. Should we understand the transcription of Anna MacDermot Roe to be noted down from Charles Byrne singing the song? Did Byrne get to the third section and realise he had pitched his voice too high, and switch down to a more comfortable lower pitch level, confusing poor Bunting?

We can also use this transcription to think about issues of tune transmission. Anna MacDermot Roe does not fit very easily into the pentatonic modes of traditional old Irish harp music, but many of Carolan’s tunes break the traditional rules or systems. Does this unease about the nature of the 6th in this minor mode tune reflect Carolan’s grappling with baroque/classical sounds from within old Irish harp tradition? Or does it reflect ambiguity in oral tradition as the tune and the song were passed down the three generations or so between the wedding and the transcription?

My header image shows an old map of Greyfield House, near Keadue, where Henry and Anna lived.

Here’s a PDF typeset version of the transcription dots on page 18, and machine audio: