At the Edinburgh Harp Festival on Tuesday April 9th, 11:00 am, at Merchiston Castle School, Edinburgh, John Purser is giving this interesting presentation:

Pìobaireachd – what it might mean for the clarsach

I have already booked a ticket – it will be fascinating to hear what he has to say. John has been working with Bonnie Rideout for some time now on the fiddle pibroch repertoire (see Bonnie’s CDs in my Emporium) and so I hope he will have some useful insights about harp ceòl mór.

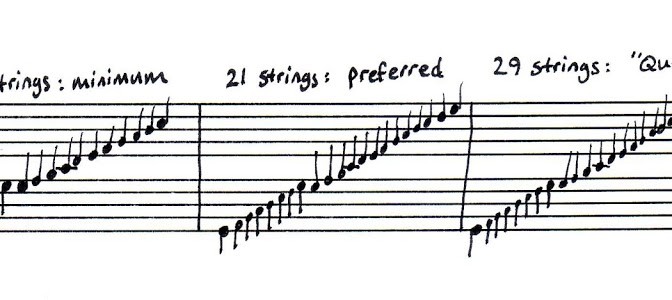

I was thinking about who has already been working on this and there are quite a few people who have recorded piobaireachd on the clarsach – Alan Stivell, Alison Kinnaird, Ann Heymann, Violaine Mayor, and more recently a number of youtube experimenters including Brendan Ring, Dominic Haerinck, Chris Caswell (who passed away very recently), and Sue Phillips. Quite apart from Grainne Yeats and Charles Guard who have recorded Burns March – in my opinion the archetypal Gaelic harp ceol mor.

Both of my previous CDs included ceol mor or pibroch – but the next one will be “wall to wall”. I have also put some experiments on youtube – here’s a very early and rough version of a classic piobaireachd that I adapted for harp:

I’ll be on site during the harp festival week with my Emporium bookstall – if you are there do come along and say hello.