news

Salve Splendor

In my Dundee class, we have been working on the Magnificat antiphon, Salve Splendor, from the 14th century Inchcolm Antiphoner, a manuscript of chant from the island of Inchcolm in the Firth of Forth.

Here are some recordings I have put together illustrating different approaches to this lovely little song.

First off, singing it straight off the manuscript page. Click here for the facsimile at Edinburgh University Library

And here are the words:

Salve splendor et pa-

Hail, glorious one and protector-trone, iubar que iusticie. Orthodoxe doctor bone pastor et vas gratie. O Columba Columbine,

light of justice,correct teacher & good, shepherd and vessel of grace. O Columba, dove-like,felicis memorie tue fac nos sine fine, coheredes glorie.

happy memories of you, give us without end, co-heir of glory.

And here is the recording:

Salve_Splendor_sung.mp3

Next, playing the song version though on the harp:

Salve_Splendor_harp.mp3

And finally, jazzing it up with some twiddles and drones:

Salve_Splendor_drone.mp3

John Knox and Mary, Queen of Scots

Here’s the flyer for an event I am doing in November, at the John Knox House and the Scottish Storytelling Centre, with the poet Henry Marsh. It should be an interesting evening.

Concerts on the West Coast

At the end of this week I am performing a couple of concerts in the West Highlands, presenting my new programme of Old Gaelic Laments as premiered (in slightly trimmed form) in Dundee yesterday.

On Thursday night, I will be at Dunollie, just outside of Oban. The seat of Clan MacDougall, Dunollie has been the scene of recent restoration and my event is to be an exclusive evening in the 1745 house. Fore more info about the house and the recent restoriation work there, please see www.dunollie.org

On Friday I’ll be further north, in Acharacle on the Ardnamurchan peninsula. This is one of the most beautiful parts of the Highlands and I’ll be performing in the community hall.

Both events start at 7.30pm. Full details are on my forthcoming events page.

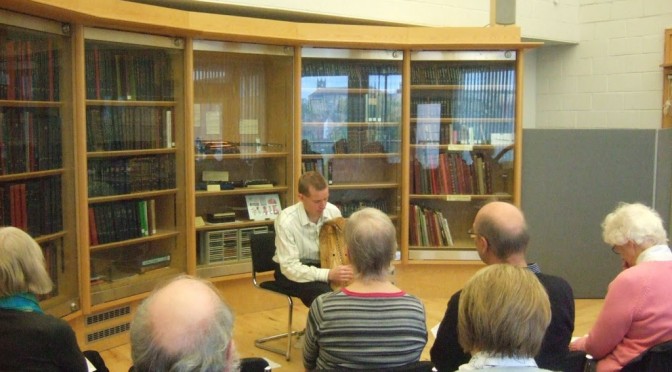

Dundee Wighton concert photo

Dundee Wighton concert

On Saturday, October 22nd, the Friends of Wighton’s monthly cappuccino concert will be performed by historical harp specialist, Simon Chadwick.

On Saturday, October 22nd, the Friends of Wighton’s monthly cappuccino concert will be performed by historical harp specialist, Simon Chadwick.

In the bright and atmospheric surrounds of Dundee Central Library’s Wighton Heritage Centre, the event starts at 10.30am with complimentary coffee and newspapers. Then from 11 to 12 Simon will perform a selection of rare and beautiful old harp tunes, using a very special replica of the famous medieval Scottish Queen Mary harp.

Simon is the regular tutor of the Friends of Wighton harp class, held every Saturday afternoon in the Wighton Centre. He has done a large amount of research with the collection of old Scottish music books housed in the centre, and his music brings back to life Scottish music from centuries past.

The Wighton Collection of Scottish music books was brought together by collector Andrew Wighton, a Dundee merchant, in the early 19th century. After his death, it was given to the city and is now housed in display cabinets in the specially built study and performance centre at the top of the Wellgate library.

Saturday 22nd October, 10.30 for 11 am

Friends of Wighton Cappuccino Concert

Old Gaelic Laments

in the Wighton Centre, Dundee Central Library, DD1 1DB

Admission £5

Followed at 2.00pm by Simon’s regular harp class. All welcome, admission £5 (£2.50 under 25s)

More details:

07792 336804

http://www.friendsofwighton.com

Schoenberg on harmony

…the composer should never invent a melody without being conscious of its harmony.

Fundamentals of Musical Composition Faber & Faber, 1967, p.3

Chords, harmonies, and other types of music

I’m currently working on a fragment of one of Robert Carver’s 16th century masses, for a music and poetry event in Edinburgh on 24th November. This lush polyphony has led me to think about and read up on counterpoint, harmony, and chords. I have long considered the dominance that chordal harmony has held over peoples understanding of music; for example, Amy Murray’s account of her discussion with an eminent composer on her proposed presentation of the Gaelic songs she had collected out West from unaccompanied singers. In response to his enquiry as to what accompaniment she would use for the songs, she replied:

“none, I think”

“That’s a mistake” said he. “My ear, as I listen, supplies the harmony. But you won’t find them making much of an effect generally unless you give them some sort of a background”. (Father Allan’s Island, p.128)

Of course, he was the one who was out of line, because the old Gaelic singers on Eriskay would not have ever used harmony with these songs, and none of their forebearers in the tradition either. But he, I imagine, was unable to imagine music without “common practice” functional harmony – his ear, he tells us, supplies it, regardless of its appropriateness.

I think that there is a case to be made – perhaps a manifesto to be composed – for a music theory and a music aesthetic of non-chordal, non-harmonic music. It could be a modern equivalent of the work of the Florentine Camerata; Galilei’s Dialogue gives us a useful model of the application of historical research into lost musical traditions informing new developments in performance and composition.

I imagine the first challenge might be nomenclature. The early baroque innovators developed the style that came to be called monody. Perhaps we are more fussy nowadays about terminological exactitude. But this can help define the bounds of what is and is not under consideration.

I would think that the main concern of such a manifesto would be to organise and promote the appreciation of unaccompanied monophony, heterophony, and drone music. It would especially be interested in unaccompanied music – the art of a single performer, which has become somewhat transgressive nowadays, with the ever increasing pressure for collaborations. But not exclusively; heterophony is intrinsically communal music, such as Gaelic psalm singing, or the kind of instrumental performance you might hear at a pub session. And the inclusion of drone music allows us to consider consonant and dissonant intervals.

As a manifesto, our text would of course have to include a critique of the old order – of common practice, chordal harmony, and of counterpoint. It would advance moral and ethical issues and arguments in favour of change.

James Taylor of Elgin’s Strathspeys & Reels

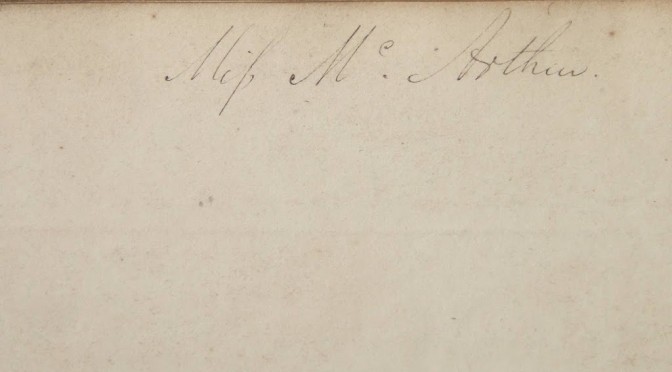

I found in an old Edinburgh bookshop, an early 19th century bound album of printed and manuscript music. It is a companion volume to one I already own, being in the same distinctive quarter leather binding and with the same name inscribed inside the front cover: Miss Mc. Arthur

This second volume has very little Scottish music in it, unlike the first volume. But one thing caught my eye; this nice collection of Scottish tunes published by James Taylor, Teacher of Music, Elgin.

The title page:

The dedication, to Lady Dunbar of Northfield:

Page 1: Lady Dunbar of Northfield’s Favourite; Lady Cumming of Altyre’s Strathspey; James B Dunbar’s Strathspey. All composed by Sir Archibald Dunbar, Bart, of Northfield.

Page 2: Mrs Hay of Westertown’s Strathspey; Lady Dick Lauder’s Strathspey; Miss Cumming Bruce, a Strathspey, all composed by the same.

Page 3: Miss Grant of Grant’s Strathspey; Mrs Warden of Parkhill, a strathspey; Miss Dunbar’s Strathspey, all composed as above.

Page 4: Miss Margaret Dunbar’s Strathspey; Mrs Cumming Bruce’s Strathspey; Lady Dunbar of Boath’s Strathspey, composed as above.

Page 5: Lieut. Dunbar (22nd Regt) Reel; Northfield House, Duffus, a Strathspey; Lady Penuel Grant’s Strathspey, all composed by James Taylor

Page 6: Miss E Grant, Lossymouth’s Reel; Mrs Brodie of Brodie’s Strathspey; Mr Brodie of Brodie’s Reel, all by JT.

Page 7: Mrs Gordon of Abergeldie’s Strathspey; Mrs Dr Gordon, Elgin, a Reel; Mrs Skinner of Drumin’s Strathspey; all by JT.

Page 8: Miss Catherine Stewart of Desky’s Reel; Miss Brander of Springfield, a Strathspey; A Lament for Mrs Tulloch, Kirkmichael; all by JT

Page 9: Miss Coull of Ashgrove, a Strathspey, by JT; Mrs Foljambe, Elgin, a Strathspey, by JT; Sir Archd. Dunbar Bart. of Northfield’s Strathspey, by a Lady.

Page 10: Miss Catherine Forsyth’s Reel, by a Lady; Mr Marshall’s Strathspey Edinburgh, by R McDonald; Mr Marshall’s Reel Edinr. by R McD

Page 11: Mrs McLeod of Delvey’s Strathspey, by R McD; Miss McLeod of Delvey’s Strathspey, by R McD; The Elgin Academy, a Strathspey, by an Old Pupil

Page 12: Leiut. Dunbar 22nd Regiments Waltz, by a Lady; A Set of Scots Quadrilles

Page 13:

page 14:

Page 15: The Surly Gallope, by a Young Lady; Mrs G Forbes, Ashgrove, a Strathspey, by a Lady

Page 16: The Earl of Fife’s Birth Day, a Strathspey by JT; The Pearl, a Strathspey by JT.

If you click on a page image you will be able to view it much larger. Let me know if you play or perform any of these tunes.