As the old tradition came to an end in the first years of the 19th century, the old harpers who were the tradition bearers seem to have played harps that were made in the first half of the 18th century. Denis O’Hampsey died in 1807; his harp was made in 1702. Patrick Quin was still alive in 1811; his harp is dated 1707 though some people argue that it is much older. The last dated instrument in the old tradition I know of is the Bunworth harp, made in 1734. There are later references to harps being made; Arthur O’Neill talks about going to the harpmaker Conor O’Kelly to oversee the completion of an instrument, which would have been after about 1750. And William Carr, who was by far the youngest of that last generation of tradition bearers, mentions having a rather poor quality harp made for him by a carpenter, apparently in the late 1790s.

All of the harps we know about that were played in the continuing tradition at the end of the 18th century and into the 19th century were large, mostly high-headed instruments. We don’t actually know what kind of harps were used by the first generation of revival students taught by Arthur O’Neill in the early 19th century; but the second generation of charity school students from 1819 on played on the big wire-strung ‘hybrid’ Irish harps made for the Belfast Harp Society by John Egan. Some of these students continued playing their big ‘hybrid’ harps down to the 1880s.

Yet the wire-strung harps made for revival purposes from the 1890s onwards don’t look back to Egan’s hybrid wire-strung harps, and they don’t even look back to the 18th century harps played by the last of the tradition-bearers. Instead, the models were the medieval Trinity College harp and the Queen Mary harp.

I really noticed this in May when I was gathering images for my Discovery Day talk. The centrepiece of the talk was our current method for re-connecting to the end of the tradition, by getting a replica of Quin’s or O’Hampsey’s harp, studying posture and hand position from Quin’s or O’Hampsey’s portrait, and working through the field transcriptions of Quin’s and O’Hampsey’s playing.

But the images of revivalists from the 1890s to the 1970s all showed small medieval harps.

Equally interesting is the way these harps were used. The slide of the Glen harp is revealing, showing Kate MacDonald playing with the harp on her right shoulder, and held very high, in a classical style and technique.

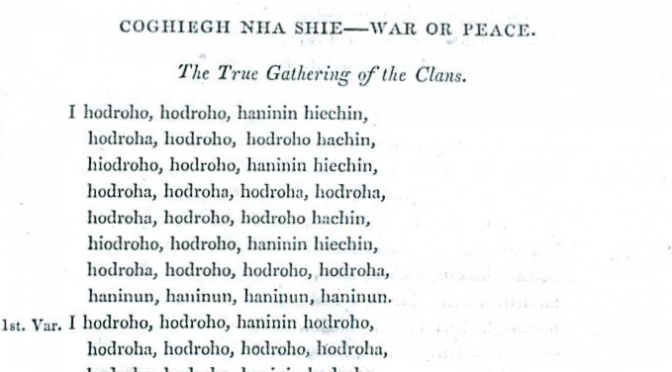

The Dolmetsch harp is shown with a photo of Edith Taylor; though we know she played left-hand-treble in the old style, what I have found about her music suggests she was playing classical-style arrangements of the “songs of the Hebrides”. Mabel Dolmetsch used one of these medieval style Irish harps to play tunes from Bunting’s piano arrangements in the 1930s.

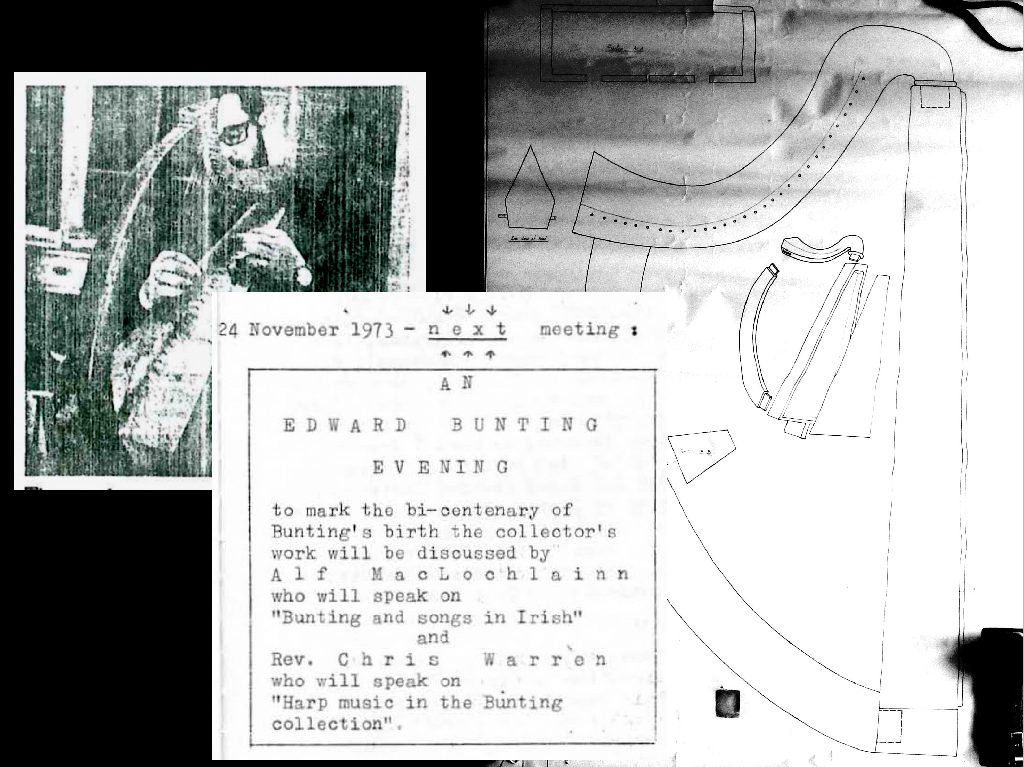

Chris Warren’s picture is especially interesting. He was explicitly working to re-connect to the end of the tradition in the 1790s and early 1800s; he worked on the “harp music in the Bunting collection”, but he used a copy of the medieval Trinity College harp.

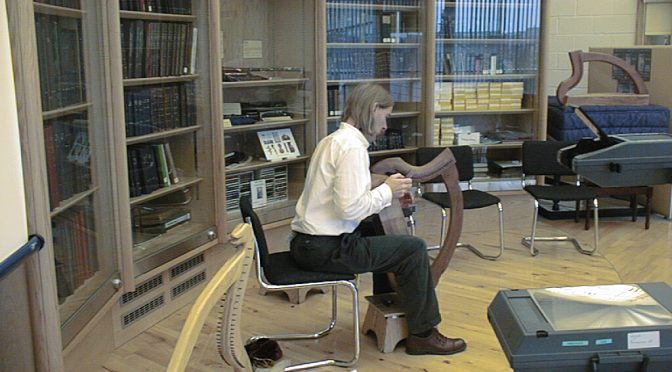

It was only with Ann Heymann in the later 1970s that we saw someone getting a copy of first Quin’s harp, and then O’Hampsey’s harp, and studying Bunting’s manuscripts with the transcriptions of the old harpers’ playing.

What is going on here? I think this is connected to the harp as symbol, vs. the harp as working instrument. The Trinity College harp as the national symbol, gave it a much stronger resonance, than the 18th century harps as the working instruments of the last tradition-bearers 200 years ago.

We need to do more research on this, to find out if anyone else was taking the big 18th century style harps seriously before Ann; and to correlate better the playing style, idiom, repertory and instrument choices of different revivalists over the past century or more.