I have been preparing the harp for some work I am planning on it. Continue reading Preparing the harp

Tag: Queen Mary harp replica

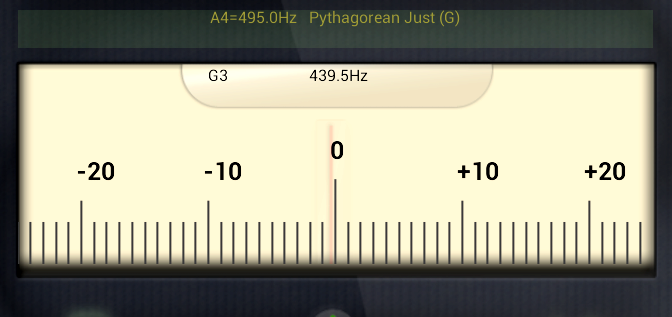

A495/370

Last night one of my gold strings popped. It was the f below na comhluighe, one of the original strings I put on the harp when it was brand new in 2007, half-hard 18 carat gold from Blundells in London.

Seeing as one of the higher gold strings had gone, I have taken the chance to redo the stringing and tuning. I took off the two gold strings above the one that went, and replaced all three with silver (the upper na comhluighe with one of my own dust-strings). And I tuned the harp to a new pitch standard of approximately A495/370.

Making silver harp strings

I have been making silver harp strings for five years. I buy in stock silver wire and draw it down to the size required, which makes it hard as well as thin.

Today I managed to take wire-making to a whole new level. I took 5 years worth of filings and silver dust, and melted them down into a little ingot which I forged into a rod, and drew down into wire. Starting with a pile of dust I finished with a piece of 0.48mm silver wire, about 32cm long.

Unfortunately there was a flaw in the wire exactly half way along, and of course it snapped there almost as soon as I started threading it into the harp.

Using a thin metal toggle I had just enough to put one half onto the highest string of my Queen Mary harp replica. It came right up to pitch and sounds great. Here it is, wound round one of the new iron split tuning pins:

I stopped annealing it at about 2mm diameter so I rekon on this being about 75% reduction – or “extra hard”. It was pretty brittle trying to wind the toggle, which I presume is from the minute flaws and inclusions from my casting, compared to the very pure metal that is produced by the big industrial producers we usually source wire from.

Now I need to repeat the process with more scrap, trying to produce a longer and thicker finished wire…

“Like medieval clockwork” – copying the missing Queen Mary harp iron tuning pins.

When I was commissioning my replica of the Queen Mary harp in 2006, I paid attention to the 30th tuning pin, which is obviously a later addition, shorter, made of iron, split end, different drive, and off the main row. This pin is now missing but I made a copy of it based on descriptions and old photos. I made the 29 brass pins with their scores on their shafts copying the museum photo of the 21 pins now in the harp, and for the 8 missing pins I made the same design of brass pins without scores.

If I had been more on the ball back then I would have noticed that those same old photos and descriptions I used for the 30th pins, also show the missing 8 from the main row, and those missing 8 are plain iron not decorated brass, and 5 of them have split ends.

So today’s project was to make 8 handmade iron pins, and install them in the harp. The contrast of the iron and brass pins is subtle but interesting in appearance, reminding me of my initial reaction to the handmade decorated pins: “like medieval clockwork”.

I broke the lowest gold B string taking it off but there was enough spare to rewind the toggle and reuse it. The string had thinned where it went over the pin – presumably a gradual process over seven years since I fitted it in 2007.

Tuning key

I lost my tuning key in Edinburgh last weekend. At first I was rather irritated; the replica Queen Mary clarsach has handmade tuning key drives, copying the original, which are rectangular rather than the usual square. So the key is also custom-made with a rectangular socket, and also has a second socket in the end of the handle to fit the square drive of the 30th pin. Basically it is useless to anyone else! I did have a rather ill-fitting spare with me

However after a while I realised this was a great opportunity. I made this key not too long after the harp was new, and while it was comfortable to use with its roundwood quince handle from the garden here, the rectangular socket was always a bit oversized and was loose on all the pins. Also it was rather “rustic” in appearance.

So today I made a new key for the Queen Mary harp. This one builds on my experience making the first. The design is the same – a T shaped pin, with a brass socket made from a rod soldered inside a tube, the end of the rod slit with saw and files to fit the drives. The second socket, from a large clock key, fits in the end of the handle. Both sockets are fixed in with little brass pins running through the wood, and secured with glue to stop them shifting.

For the handle of this key I used a piece of ancient Irish bog oak which Davy Patton gave me years ago. I had thought of carving medieval West Highland designs into it, and even gilding the designs, but as the handle took shape it became very spare and elegant. The bog oak does not carve very cleanly anyway. So in the end the only decoration was a pair of parallel incised bands at each end of the handle and each end of the main socket shaft, echoing the pairs of incised bands on the Queen Mary harp tuning pins.

I have to make another soon as my student who has the Student Downhill harp has lost the key for it. It ought to have a brass socketed key anyway as the commercial steel-socketed key it used to have was starting to chew up the decorated brass pins I have started fitting to it. Which reminds me, I need to finish the set of brass pins for that harp. So many jobs lining up…

Silver harp strings

At the beginning of January I was fiddling with the setup of my harp, as part of an ill-fated New Years Resolution to change its tuning. For the last two months I have had 10 gold, 10 silver and 10 brass strings on (nominally), which I liked because of the neatness and symmetry of the counting.

Taking the silver 3 notes higher than it ever used to be, up to an octave above middle c, must have emboldened me. The silver I am using now, and the way I am drawing it hard, seems to work very well for thinner higher pitched strings.

Also I have been pondering the Ouseley quote about the silver strings on the Trinity College harp.

So the latest scheme (pictured below) takes the silver right up to the top of the harp. The only exception is the very highest string which still has Dan Tokar’s experimental super-hard-drawn gold wire from years back. I just can’t bring myself to remove it!

The sound of the high silver is nice, more creamy and fluid that the brass. I think I always felt that the high strings on this harp were a bit pingy; I swayed between thinking that the treble end of the soundbox is too thick, or thinking that it is meant to be pingy as a contrast with the singing midrange and the roaring bass, or thinking that if I could only get the right type of brass (red brass, yellow brass, hard-drawn, latten…) then it would become perfect.

Now I will watch how these high silver strings hold up for a couple of weeks. If they behave themselves then I’ll probably keep them going for a while.

Some thoughts on replicas of old instruments

To me the extant surviving instruments are like treasure-houses of detailed specific data about not only the historical instrument design and construction, but also about all other aspects of the historical music-making (because of the presumption that the original instruments were commissioned by discerning musicians).

So I would regard every last detail about the old instruments as having something important to tell us. And as a player investigating the old music traditions, I want a replica harp that is as close as humanly possible to the old museum examples.

Of the two oldest Gaelic harps, the Queen Mary and the Trinity College harp, I would say they are remarkably similar in design and construction, and that similarity points to a shared conservative instrument-making tradition and a shared conservative music-making tradition, covering Ireland and Scotland. Similarities between them I take to be confirmation of that shared tradition; differences between them become specific individual features of that particular instrument. (you can do the same exercise with the later harps but there are more differences then. The Trinity & Queen Mary are by far the most similar pair I would think).

The Queen Mary harp is far easier to consider since a lot more info has been published on it, mainly the study in 1904 by R.B. Armstrong and more recently Karen Loomis’s ongoing study of it which is published in interim in the Galpin Society Journal 2012. The Trinity College harp is far less well studied or published; the information in Armstrong’s 1904 book is a lot more sketchy and has as I understand it at least one misleading error; and there has not been any further more recent published work than that.

When I commissioned my own harp (which is a copy of the Queen Mary harp) I insisted that my maker simply copy every aspect he could see with as much fidelity as possible, from selection of timber through to decoration and even the idiosyncracies of individual fittings and adjustments. The idea being to end up with a new instrument that was as close as possible to handling the real thing in as many respects as possible. Since then, Karen Loomis’s work producing 3D X-ray models of the instruments and materials analysis, has revealed important structural and decorative information that would have led to some different decisions being made with my copy, but that is part of the learning process, and Karen’s study has directly addressed certain questions which were raised by my commission.

When I commissioned my own harp (which is a copy of the Queen Mary harp) I insisted that my maker simply copy every aspect he could see with as much fidelity as possible, from selection of timber through to decoration and even the idiosyncracies of individual fittings and adjustments. The idea being to end up with a new instrument that was as close as possible to handling the real thing in as many respects as possible. Since then, Karen Loomis’s work producing 3D X-ray models of the instruments and materials analysis, has revealed important structural and decorative information that would have led to some different decisions being made with my copy, but that is part of the learning process, and Karen’s study has directly addressed certain questions which were raised by my commission.

When I worked with David Kortier on the HHSI Student Trinity Harps, this was a somewhat different project. The initial aim here was simply to obtain a set of affordable harps for use in summer school classes. We were not satisfied with any commercially available models so we approached Kortier to discuss options and he ended up making a custom student model for the Historical Harp Society of Ireland. The main design criteria for this student harp were that it be affordable and quick to make, but that it present a student in class with the string count, string spacing, ‘feel’, and overall ergonomics of the original harp. So you see there was no attempt made to reproduce the subtleties of construction or decoration; but from the beginning the exact geometry and ergonomics of the strings were the most important thing. This was so that a class student given one of these harps would instantly be learning the finger movements and playing techniques exactly as on a proper replica (i.e. exactly as on the real thing!), even if the nuances of sound and response were not as accurate as could be obtained by a proper replica.

We based the first HHSI Student Harp on the Trinity College harp because it is the Irish national symbol and this seemed appropriate. Kortier had visited Trinity College and inspected and measured the original some time before, so he was able to use a lot more than just the published data; even so there were a number of details that had to be guessed or interpolated simply because the data about the original is not available. I mean the data is there, it exists, but it is locked away inside the fabric of the instrument itself and would need a long term detailed programme of scientific analysis like is happening in Edinburgh, to discover it.

So in summary, reconstructing an instrument from the surviving old instruments really needs a partnership between high-tech scientific analysis of the original, and a highly skilled sensitive craftsman-artist. In practice, you have to compromise and make do with what you can get – most of the compromise to date being on the analysis side I have to say. I hope that the recently published ongoing work in Edinburgh will soon feed into the work of the artist-craftsmen and we start to see really high quality accurate replicas that take on board and accurately reproduce these important new discoveries about the detailed features of the old harps.

Every level of data is vital – from the large scale measurements of height, width, string count and string lengths etc, down to tiny details of alignment and adjustment and profiling, all combine to give a very particular playing experience of the musician with important implications for what is and is not idiomatic for that particular instrument – and as our mission is to rediscover the lost old historical idiom, it seems to me that the idiom of each specific historical instrument (or rather, the imperfectly recreated idiom of each attempted reconstruction) is a vital tool for this. And that means that each reconstruction has to be as close as humanly possible to the specific museum original to have any value in that process.

Harp string labels

Recently I wrote a new page on earlygaelicharp.info, about possible inscriptions on the Queen Mary harp. As part of this I reviewed my photographs of the labels glued on the harp labelling some of the strings, and then I had the idea of photoshopping and cleaning up the photos, scaling them, printing them out and glueing them onto my replica in the appropriate positions.

For those of you with a Queen Mary replica who want to join in the fun, here is the image I ended up with. Print it out at 486dpi onto good old fashioned white or off-white laid paper, cut out along the black edges, and stick on using flour and water paste. The numbers go on the right hand side* of the string band (so they are visible for a left orientation player), and they are upside-down when the harp is in playing position, so the player can read the letters. They go in order, counting from the treble: 1 [illegible], 8 [c], 9 [b], 11 [G], 15 [C], 22 [C].

Any problems or questions let me know! If you send in a photo of your harp with the labels stuck on, I will feature it here!

*Right and left hand side of the harp are described as from the viewpoint of the player, not of an onlooker