On Thursday I was at the National Museum of Scotland store in Granton, a suburb north of Edinburgh. I went there with Karen Loomis, to look at the plaster-cast of the Trinity College harp which is kept in the store. We had a very productive hour, inspecting, measuring and photographing the cast, and discussing aspects of the cast and how it related to the real thing in the Long Room at Trinity College, and to later illustrations and depictions of the harp.

The plaster cast is painted all over, so from a distance it actually looks very much like a real old wooden harp. The main body of it is painted with streaky dark brown, while the metalwork is picked out with silver and gold paint. There are two nice coloured glass cabochons in the setting at the end of the neck. The tuning pins are seperately cast and inserted.

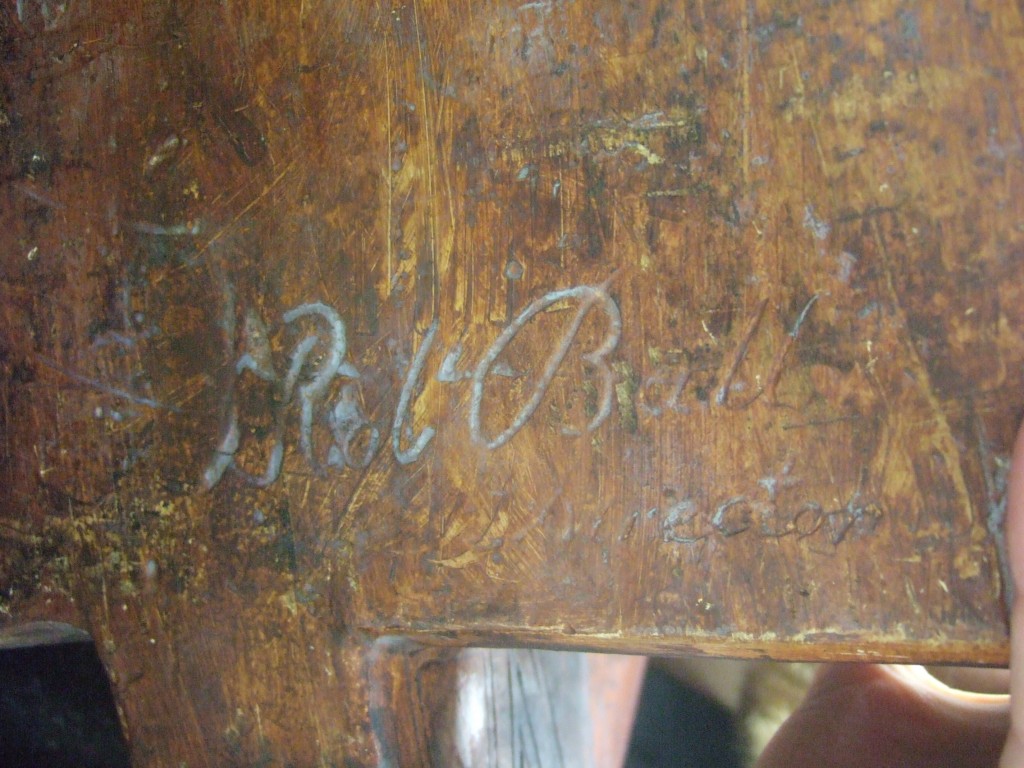

The cast is signed and dated on the back: Robt Ball 1847. There is quite a lot more written on the back but I am having trouble reading all of the inscriptions from my photos – the NMS staff tipped the cast over a little to allow us to take photos, but they couldn’t lie it right down because of the fragility of the cast especially the tuning pins. And because it is on the back, the plaster is quite scratched and worn away so some sections of the lettering are almost gone. Here’s what I have so far:

The Origi[nal]

commonly called

The Harp of

Brian Borom[e]

in the

DUBLIN UNIVERSITY MUSEUM

this model is present[….]

Robt Ball

[….]rector 1847

Graham Steele, who discovered the inscription during his visit to see the cast back in August, pointed out that Robert Ball of Dublin University Museum had produced a broadsheet dated July 1853, titled The Harp of Brian Boroimhe – Restoration of the ancient harp preserved in the Dublin University Museum, and commonly called the harp of Brian Boroimhe. A manuscript annotation on the reproduction I have, states “exhibited in the great exhibition Dublin 1853”. There is a second sheet, Restoration of the harp known as the Dalway harp also by Robert Ball July 1853, and also with the same ms annotation.

This sheet was previously assumed to have described (and therefore also dated) the re-building of the Trinity College harp in the mid-19th century, when the iron straps (as seen on early 19th century illustrations) were removed, and the base of the box and pillar made up with white plaster in a strangely long foot and scroll, as seen on my old photo postcard.

However, reading the sheet again, I noticed it describes “the tradition attached to the original harp…” (my emphasis). I also noticed that the Dalway sheet says “The harp appears to have been painted with brilliant colours, but as they were probably not part of its first adornment, they have not been copied In the Restoration.” (my emphasis). In other words, I think that Ball is using the word “restoration” to mean “plaster-cast reconstruction”, rather than “rebuilding of the original”. The same “restoration” term is used in a report in the Illustrated London News, 1st November 1851:

“This restoration is made in the hope of inducing artists to adopt it as a model in emblematic devices relating to Ireland”.

R.B. Armstrong in his 1904 book The Irish and Highland harps describes a number of these casts in museums; I know of three, the one in the NMS, the one in Collins Barracks (National Museum of Ireland), and one at the Met Museum, which the staff there tell me was de-accessioned and sold in the 1980s. The Met catalogue of 1902 lists both the Brian Boru harp cast and also the Dalway harp cast, and says that both were “obtained through the kindness and courtesy of Mr T.H. Longfield, of Trinity College Museum”.

Armstrong discusses these casts, and he is very scathing about them; he is very critical of the artwork which he explains has been redrawn on the casts, so the artwork on the casts does not represent the artwork on the real harp. He draws attention to the places where the original designs are missing or damaged, and the cast-maker has invented new ornament to fill the spaces, particularly the left side of the soundbox, and the base of the pillar and the projecting foot. But looking closely at areas where the ornament on the original is well-preserved, it is clear that on the cast everything has been re-drawn, to a lower standard than the original, and without a full understanding of the nature of the foliage and interlace motifs.

One of Armstrong’s complaints in 1904 was that illustrations of the cast were published in learned journals as if they were illustrations of the original harp; and the spurious decoration on the left side of the soundbox and on the projecting foot particularly provoked his ire. I think he was especially irritated by Charles Bell’s 1880 article in Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland describing the Queen Mary harp and the Lamont harp when they entered the Museum in Edinburgh. Bell illustrates a woodcut engraving of the Queen Mary harp, and of the Lamont harp, and then for comparison illustrates a woodcut engraving of the Trinity College harp. Unfortunately, though he doesn’t say so, it is actually an illustration of one of the casts, showing the spurious left side of the soundbox. You’ll also see if you compare my Trinity Neck Decoration sheet, that the neck decoration on Bell’s illustration matches the cast, but deviates somewhat from the real thing.

However this got me thinking. Karen and I discussed at some length the shape of the projecting foot. On the real Trinity College harp, this area is completely rotted away. Between c.1850 and 1961, the real Trinity College harp had the strangely long and square-ended foot with the scroll or knob at the base of the pillar.

The cast has the too-long projecting block and the knob, however, it differs in having the foot rounded, not squared-off. You can see the difference if you compare my photo-postcard of the actual harp above, and the photo of the cast below.

For a long time I have been saying how the iconic use of the Trinity College harp as the national emblem of Ireland, shows the harp in its pre-1961 state, with the long projecting block, and with the curious scroll or knob at the base of the pillar.

However looking again at Percy Metcalfe’s design on the coins, I notice two features I had not been paying attention to before. Not only is the projecting block curved, rather than squared off, but the left side of the soundbox carries the spurious decoration of the casts, rather than the genuine decoration of the original harp.

Most accounts of the designing of the Irish Free State coinage in 1927, say how the various invited artists were sent “a photograph of the harp”. Interestingly, the two harps chosen by the Government were the Brian Boru harp and the Dalway harp – the two which Ball had made casts of in the 1840s.

The photographs were, according to one source, taken by George Atkinson, Headmaster of the School of Art, on behalf of Archibald McGoogan of the Art Department of the National Museum. If we could find a copy of this photograph in the archives somewhere, that would settle it for sure.

It seems to me highly plausible that the Irish national emblem is not actually modelled directly after the Trinity College harp, but is instead modelled after Robert Ball’s Victorian plaster-cast.

A question: was the real Trinity college harp re-built before, or after, the cast was made by Robert Ball in 1847? If before, why did Ball not make the cast’s foot the same square shape as on the real harp? I suspect the plaster cast was done first, and then the real thing was re-built later, following the shape of the plaster-cast approximately but not exactly.

One final question. In the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland for 1881, is the following notice:

MONDAY, I0th January 1881.

…The following Donations to the Museum and Library were laid on the table, and thanks voted to the Donors :—

(1.) By Mr ROBERT GLEN, 2 North Bank Street.

Cast in Plaster of the Harp called the Harp of Brian Borumha, preserved in Trinity College, Dublin. (See the preceding communication by Mr. Charles D. Bell, F.S.A. Scot).

So Robert Glen donated the cast to the National Museum? I presume this is the cast we were looking at in the NMS store. Glen was a very well respected Edinburgh instrument maker, producing very good bagpipes, and in the 1890s he made a number of very high quality replicas of the medieval Gaelic harps, including a fully-decorated Queen Mary harp replica now in private hands in Australia, and a harp styled after the Trinity College harp now in private hands in England. (info on both here). This latter harp includes many original features (such as foliage based on the Queen Mary harp decoration), but it shares many features of the cast, including the curving foot and knob, and the same distinctive left-side decoration of the cast soundbox. It looks like Glen was using the plaster-cast as a model for his working replicas.

Thanks to Karen Loomis for arranging the meeting; thanks to Jackie Moran & Lindsay McGill for hosting us at the museum store. Thanks to the National Museum of Scotland for allowing access and allowing photography – the corollary of that is that all my photos of the cast are © National Museum of Scotland.

From https://designresearchgroup.wordpress.com/2008/03/28/design-and-change-the-oireachtas-harp-and-an-historical-heritage/

“In August 1923 the Executive Council determined that the “Brian Ború Harp” would be the basis of the new seal. The photograph of the harp, provided by Hugh Kennedy was taken by George Atkinson Headmaster of the School of Art on behalf of Archibald McGoogan of the Art Department of the National Museum.”

So the Great Seal of the Irish Free State, which was designed in 1923, a few years before Metcalfe did the coin designs, was also based on a photograph of the cast in the National Museum.

Again, thank you Simon, for sharing your amazing research.