Passing by Drumshanbo recently, I took a moment to stop and look for traces of Jerome Duignan.

Edward Bunting published Arthur O’Neil’s story about Duigenan, which is fairly well known:

Some curious tales are told of Jerome Duigenan, a Leitrim harper, born A. D. 1710. One is of so extraordinary a character, that, were it not for the particularity of the details, which savour strongly of an origin in fact, the Editor would hesitate to give it publicity. He is, however, persuaded that he has it as it was communicated to O’Neill, between whose time and that of Duigenan there was scarcely room for the invention of a story not substantially true. It is as follows. “There was a harper,” says O’Neill,” before my time, named Jerome Duigenan, not blind, an excellent Greek and Latin scholar, and a charming performer. I have heard numerous anecdotes of him. The one that pleased me most was this. He lived with a Colonel Jones, of Drumshambo, who was one of the representatives in parliament for the county of Leitrim. The Colonel, being in Dublin at the meeting of parliament, met with an English nobleman, who had brought over a Welsh harper. When the Welshman had played some tunes before the Colonel, which he did very well, the nobleman asked him had he ever heard so sweet a finger. ‘Yes,’ replied Jones, ‘and that by a man who never wears either linen or woollen.’ ‘ I’ll bet you a hundred guineas,’ says the noble- man, ‘ you can’t produce any one to excel my Welshman.’ The bet was accordingly made, and Duigenan was written to, to come immediately to Dublin, and bring his harp and dress of Cauthack with him; that is, a dress made of beaten rushes, with something like a caddy or plaid of the same stuff. On Duigenan’s arrival in Dublin, the Colonel acquainted the members with the nature of his bet, and they requested that it might be decided in the House of Commons, before business commenced. The two harpers performed before all the members accordingly, and it was unanimously decided in favour of Duigenan, who wore his full Cauthack dress, and a cap of the same stuff, shaped like a sugar loaf, with many tassels; he was a tall, handsome man, and looked very well in it.”

Ancient Music of Ireland 1840 intro p. 77

Bunting is quoting here from Arthur O’Neil’s Memoirs, and we can look at the manuscript original to see that Bunting has silently omitted O’Neill’s fruitier details:

it was unanimously decided in Duigenan’s favour, and particularly by the English Nobleman himself, who exclaim’d “Damn you why don’t you wear better clothes” “Och says Duigenan I lost my all by a Law suit, and my old nurse for spite won’t let me wear any other clothes” “Damn me, but you shall,” and then put a Guinea into his own (thick) hat, and then went round through the members, who every one threw in a Guinea each, so that the Nobleman’s Hat was nearly half full, which he put into Duigenan’s pockets… Poor Jeremy contrived to spend the chief part of his money before he left Dublin.

Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.14 page 34-5

Arthur O’Neil’s rough draft of this story is QUB SC MS4.46 page 25. A Guinea (a gold coin worth 1 pound and 1 shilling) would be the equivalent of perhaps £200 today, and it seems there may have been a couple of hundred members of parliament. Even if only some were there that is still quite a lot of money to spend on gallivanting round the city!

I remember a vague suggestion that the “English nobleman” may have been Sir Watkins Williams-Wynn, and the Welsh harper may have been John Parry, but that may just be wild speculation, and I am not finding the reference or source for this notion, or whether there is anything substantive to suggest Williams-Wynn was in Dublin in the mid 18th century.

A second independent tradition

Mike Baldwin posted about a traditionary story in the Schools Collection from the 1930s, which describes the episode of Duigenan playing in the parliament in Dublin, but with different detail. This version was written down by the schoolchild Sarah Mc Manus in the 1930s, using information told to her by her father, Michael McManus. She writes:

The following story was told to me by my father about Jeremy O’Duignan the Harper.

“The Schools’ Collection, Volume 0207, Page 091” by Dúchas © National Folklore Collection, UCD is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

A harper named Jeremy O’Duignan once lived in the townland of Murhaun a mile outside the town of Drumshanbo and a quarter of a mile from Lough Allen. His house was built on a field beside the road which is now owned by my father Michael MacManus. Round the ruins of the cottage stand a group of trees inside which is a large stone known as “Cloc-na-Clairseacha”.

An English noble accompanied by his Welsh harper arrived in Dublin. The English noble boasted greatly about his harper and said that no harper could equal him.

Colonel Jones who was from Drumshanbo and a member of the Irish Parliament representing Leitrim heard the boast and bet a hundred guineas that he would produce a harper not alone as good but better.

He then sent for O’Duignan who went on the stage coach to Dublin where he was met by Colonel Jones and was taken to the old Parliament house at College Green where the contest was to take place.

A large crowd had assembled at the Parliament house to see the entertainment. The Welsh Harper was first to play and he did so well that Colonel Jones got uneasy.

O’Duignan did not seem nervous and when it came to his turn he got on the stage and said “For old Drumshanbo’s sake” At first he played a lively air known as “O Rourke’s Noble Feast” but gradually it changed to a low wailing air called “Limerick’s Lamentation” and before he had finished there was not a dry eye in the audience.

He was wildly applauded and was adjudged the victor. His pockets were filled with gold and he spent a royal time playing at concerts and banquets. When poor O’Duignan arrived back in Drumshanbo he got a great reception from the residents but all he had was his faithful harp.

In the year 1798 when the French camped in Mahanah O’Duignan entertained them by playing his harp and on the following day when they left on their way to Ballinamuck he marched before them playing his harp

In this version we have a hint of Duigenan spending all the money before he got back home; we don’t have any mention of his outfit, but we do have fascinating information about the tunes he played, and where he was from.

The tunes

I first noted this story in a comment on my post on O’Rourke’s Feast, and there’s not much more to say at this stage. I only know of one live harp transcription of Pléaráca na Ruarcach; it is on QUB SC MS4.29 page 107 and may have been transcribed from Arthur O’Neill, or from Rose Mooney, in the 1790s but I don’t really know. It is in G major and requires F♯ to be tuned on the harp. I also know of only one live harp transcription of “Limerick’s Lamentation”, on QUB SC MS4.33.1 where it is titled “Lochaber”; this seems to be part of the set of transcriptions taken from Patrick Quin in around 1800-1802. It looks like it should be in D major, and would require F♯ to be tuned on the harp Because both of these settings require F♯ on the harp, they can be played together as a set; I have tried and they go very nicely together. I will try and make a video or recording at some point.

The outfit

I’m not having much luck finding more information about the “Cauthack” outfit that Arthur O’Neill mentions. I presume this is a corrupt spelling of an Irish word. Anne O’Dowd has written a lot about the use of rushes in Irish folk life, but I don’t have access to her book Straw, Hay and Rushes in Irish Folk Tradition. She wrote an article in Béaloideas 79, 2011, which concentrates on floor covering but includes information about rush mat weaving, including an 18th century drawing, which I assume would be related to Duigenan’s “cape”. We need to do more digging about this.

It is also not clear from O’Neil’s account whether the “Cauthack” outfit was something peculiar to Duigenan; or if it was a regional thing from around Drumshanbo; or if it was something associated with harpers.

The places

Arthur O’Neil tells us that Duigenan “lived with a Colonel Jones, of Drumshambo”. I’m assuming this was Theophilus Jones of Headfort who was MP for Leitrim from 1761, though it may have been his grandfather. I haven’t researched Jones; he may have had a house in Drumshanbo, or Duigenan may have spent time living at Headfort.

Sarah McManus gives a good amount of detail about where Duigenan’s cottage was. Writing in the 1930s, she says “Jeremy O’Duignan once lived in the townland of Murhaun … His house was built on a field beside the road which is now owned by my father Michael MacManus. Round the ruins of the cottage stand a group of trees inside which is a large stone known as ‘Cloc-na-Clairseacha’.”

You can see on the Townlands map that Murhaun (Motharán) townland is a little north of Drumshanbo and a little East of Lough Allen. There are two roads running north-south through Murhaun, the main road (R207) running up the East side of the townland, and a lane parallel and to the West. If we trust the distances Sarah gives, we might suppose that the ruins of Duigenan’s cottage might be in the north-western corner of Murhaun townland, beside the main road. But she may mean that the townland in general is that far from the town and the loch, not meaning to specify the cottage ruins within the townland.

I checked the old maps, and the Griffith valuation. We can see that in the 1850s, Thomas McManus held lots 1, 2, and 3, covering much of the northern half of Murhaun townland. Of course, landholdings may have changed between the Griffith valuation of the 1850s and the Schools collection in the 1930s; we need local knowledge to help us here. I also checked the National Monuments Service Records, but there is no standing stone listed in Murhaun.

I walked along the main road, looking over the hedgerows. To the west of the road, the land falls away steeply to the stream, and is very overgrown, the fields engulfed with regenerated woodland. To the east of the road, the land rises steeply, and has small fields surrounded by trees, with good cattle grazing. I did see groups of trees, but I saw no trace of a ruined cottage or a stone. This photo is looking East from the R207, at the northern edge of Murhaun townland, where the road passes over the stream:

And this next one is a 3D anaglyph looking down the slope from the road to the West, showing how the fields between the road and the stream have turned into regenerated natural woodland (red/cyan goggles needed to view in 3D)

Could the stone and the cottage ruins be down there by the stream?

I also went along the lane that runs parallel to and west of the main road. This lane rises over the hill. A little south of Murhaun townland, the road passes the old churchyard:

Here is a typical view over the hedge on this lane, looking south-east:

I found it very helpful to see the landscapes around here, but I think it will not be possible to identify more closely which field Sarah McManus was talking about, without speaking to people in the area who have the local knowledge and information. I feel it is likely that the stone is still there but totally hidden or buried in the undergrowth or hedges.

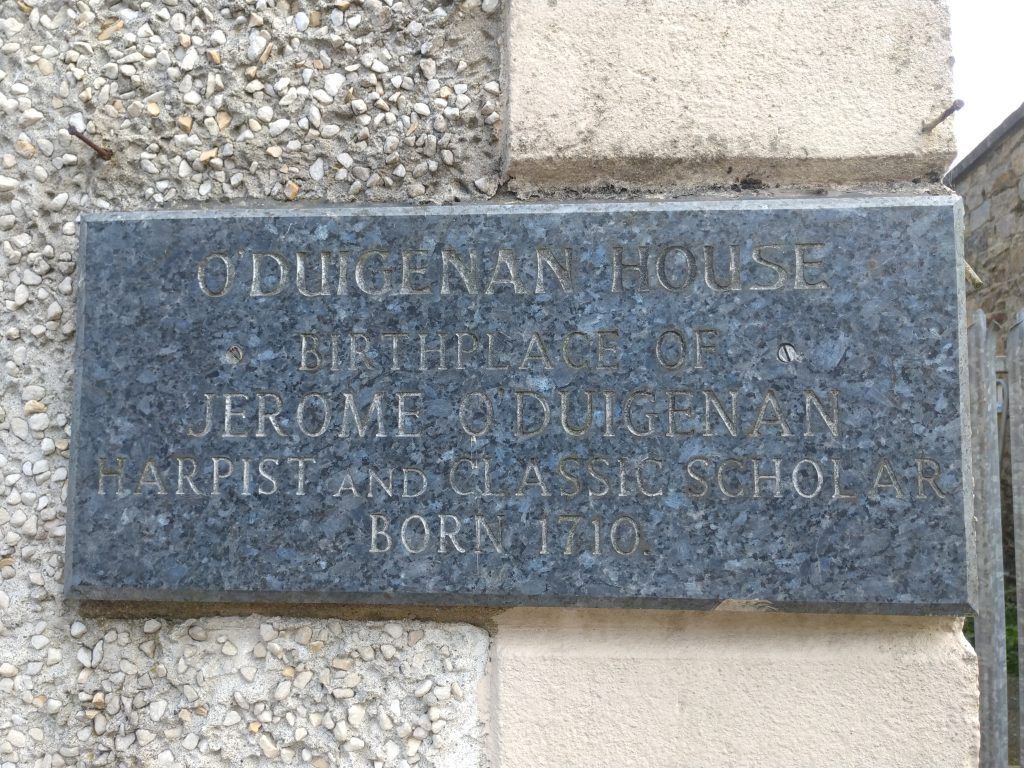

There clearly are local traditions and knowledge about Duigenan in the area. As you go south down the lane after the old churchyard it turns into Convent Avenue and runs right to the centre of Drumshanbo, where there is a house with a stone plaque on it:

In summary: I had an interesting little wander around Drumshanbo and Murhaun, and got a real sense of Duignan’s world – the sighted, literate Greek and Latin scholar, rooted in the deeply rural Leitrim countryside. But more work is needed.

My header images shows the view West from the edge of Murhaun townland, over Lough Allen. You can see reeds or rushes growing at the edge of the lough.

Many thanks to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for helping to provide the equipment used for these posts, and also for supporting the writing of these blog posts.

Niamh sent me a reference from the Foclóir Gaeilge–Béarla online, for the word cáiteach, which has an alternative spelling cáiteog, defined as “1. Article made of bass, bark. 2. Mat”. This may be the word Arthur O’Neil dictated and which the secretary Thomas Hughes wrote down as “cauthack”.

I forgot to check Donal O’Sullivan’s edition of the Memoirs in his Carolan (1958), since he often gives normalised modern spelling of Arthur O’Neill’s Irish words. On vol 2 p.159 he tentatively suggests cáiteach.

I really enjoyed reading this. Jerome Duigenan is new to me: I came across his name as while looking at the tune “An Leanbh Aimhréidh” (The Troubled Child), which Petrie attributes to him. Do you happen to know whether that attribution is considered accurate?

Thank you Rebecca for this, that’s a great snippet of information to add to the mix.

It looks like this information comes from Stanford-Petrie no.591 which is titled “The peevish child / by Jerome Dingenan”. I don’t know Petrie’s source, and so I don’t know whether we can trust this information or not.

Bunting has a version of this tune. What may be his live transcription dots is in QUB SC MS4.33.2 page 77, titled “The Lán of Ivre / The Restless Child” (obviously an attempt to write the title phonetically). He makes a piano arrangement in QUB SC MS4.30.12 titled “The Lan of Ivreagh / Mrs Connor Belfast” so I guess she was his ultimate source for the tune. I haven’t found more information from Bunting about the tune.

We should collate the versions in the other sources (Joyce etc.) to see if we can get any further than this.

Petrie’s “By” could represent a tradition that Duigenan composed the tune, or it could represent a tradition that he played it to someone in the 18th century who wrote it down and passed it on to Petrie. I wonder if there is more info in Petrie’s unpublished papers.

Ann O’Dowd, Straw, hay & rushes in Irish folk tradition has been reprinted; (Irish Academic Press 2015, reprinted 2022). She mentions Duigenan on p.305, but there is very little detail; she also discusses the straw costumes used in seasonal activities (e.g. the photo on p.104). Apart from the passing mention of Duigenan, she only refers to straw outfits, and I’m not seeing any further information about clothes made from rushes.

I do however note “cadó” as a blanket, which may well be Arthur O’Neil’s “caddy”.

Douglas Hyde, Amhráin Chúige Chonnacht / The Songs of Connacht I-III (Irish Academic Press 1985) p.46-8 has an interesting story that mentions Duigenan:

“Bhí an Duibhgeanánach ina fhear mór garbh, agus ní shílfeadh duine ar bith go raibh aon eolas ar cheol ag stróinse agus straoille dá shórt” (“Duigenan was a large, coarse man, and nobody would think that a clown and lout of his sort could have any knowledge of music”)

Actually the whole story has an echo of the one quoted above, from O’Neil and McManus. St George had a large wager with some Englishmen, that he had “fear-buachailleacht na mbó agus fear dall” (a cow-herd and a blind man) who had more skill and knowledge of music and the harp than any man in England. This seems to be the reason for St George summoning Duigenan and Carolan to Dublin (I assume Carolan is the blind man and Duigenan the cowherd). However, instead of the Englishman or men coming to Dublin, St George got the harpers drunk and kidnapped them and took them to England. We are not told any more about the outcome of the wager, because the story switches to focus on Carolan being in England and composing a song Uilleacán Dubh O.

I made a video of Duigenan’s set, that he is said to have played in the competition in Dublin.