I first came across the song of Ailí Gheal Chiúin Ní Chearbhaill from the singing of Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin. You can read her commentary about this song in her book A Hidden Ulster (2003) p.220-223, or on her Oriel Arts website where you can also see a video of Pádraigín singing the song with harp accompaniment by Sylvia Crawford.

Because I was already familiar with Pádraigín’s singing, I was able to recognise the tune of this song in Edward Bunting’s transcription notebooks, on the top stave of Queen’s University Belfast MS4.29 page 204/202/211/f100v. In this post, we will look at that transcription notation, and then look at the wider context of this tune.

Edward Bunting’s live transcription notation

The first stave of MS4.29 page 204 has two titles written above what looks to me like a live transcription notation. The first title is in ink, perhaps done at the same time as the music notation, and reads “The Pearl of the Irish nation”. A second title “Alle ne hune ne Carolan” is written in pencil and may have been added later, though I think it is also in Bunting’s hand.

You can see that Bunting has deleted some notes and there are a few places where he gives two different passages at the same time; the initial writing is all stems pointing upwards, but the replacement passages mostly have stems pointing downwards. I have made two machine audio mp3s. The first plays through the initial deleted notes; the second plays through the “corrected” notation. Not all of my readings are completely confident but still, this gives you an idea of what he has written.

The tune is fairly clear, with four lines, the second being a repeat of the first. I have transposed the tune down one note for my PDF typeset version and machine audio, which puts it into a harp tuning with F sharp, and makes the tune D major. I notice on my tune list spreadsheet there is another possibly one-up notation on page 200; it is also possible that this notation is at pitch in E major. That is not a harp key, but it may be a vocal transcription.

I do not know whether Bunting’s initial deleted notes are accurate transcriptions that he has decided to “improve” on by changing the tune according to his own arranging ideas; or if he misnoted the tune first time through, and deleted his errors and re-wrote to capture more accurately what the informant was singing or playing. That is why I have given you both versions.

Everything else on this page is unrelated. Under our tune, there are two titles in cartouches or curly brackets. The first is “Darling of my heart or / Charia mo Chleamh” and the second is “Slaunte an Hoppo or / Health from the Cup”. Under these two titles is a neat copy of a different tune, and at the bottom of the page is a tag “from Priest Cassidy”. I don’t have anything to say about any of this at the moment.

Bunting’s piano developments of the tune

I think that this notation at the top of MS4.29 p.204 represents the live transcription of what Bunting’s traditional informant sang or played. However, Bunting’s mission right from the start was to “transcribe and arrange” the music, and to publish it for piano, and so all of his other versions of this tune are more or less heavily adapted to bring them into Bunting’s late 18th and early 19th century piano style.

Bunting made a piano arrangement of the tune of Ailí Gheal in his unpublished 1798 Ancient and Modern piano collection. The arrangement is in QUB SC MS4.33.3 p.51. His title there is “Allié gheal chuin ni Chearbhuil – or Pearl of the Irish nation”

You can see and hear at once that Bunting has hugely de-traditionalised this tune by arranging it for piano. He has arbitrarily changed the key to give 3 flats, putting this piano arrangement into B flat major. The main thing he has done is to change the tune in the penultimate bar of each line.

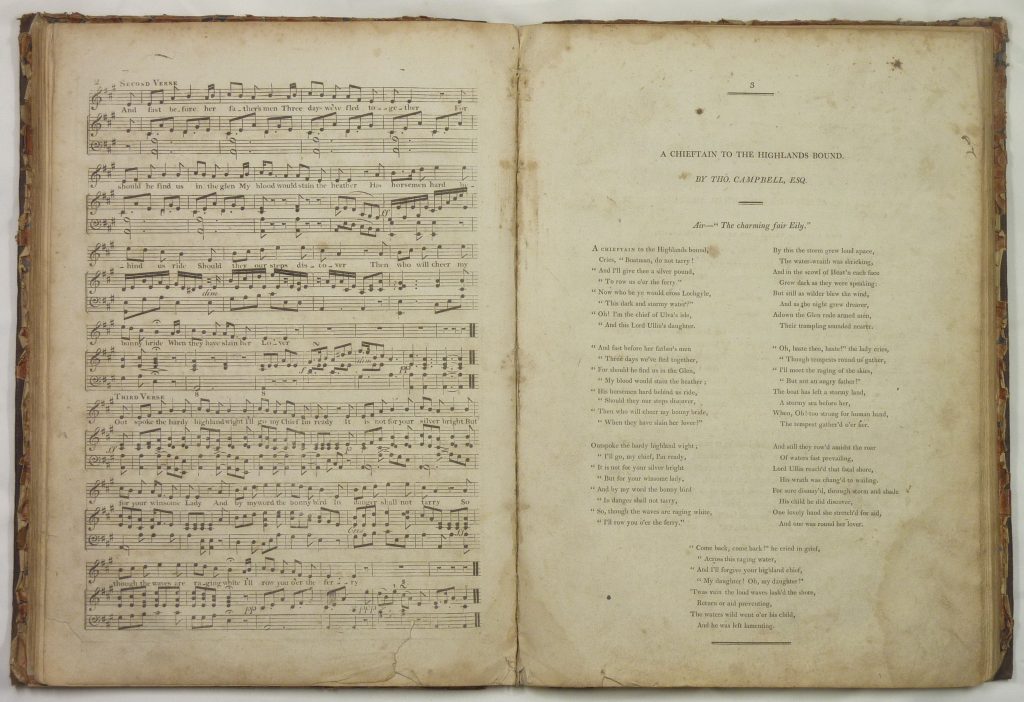

Finally, Bunting published a vocal and piano arrangement as the first item in his 1809 collection, on pages 1 to 3. His title for the tune is “Eilighe Gheall Chiun / Eilighe Gheal Chiun / The charming fair Eily” and his setting I think shows us what he was aiming for even as he went out visiting the old harpers and singers and dotted their tunes down into his little notebook:

This is Bunting’s world. This is the music he lived and breathed. This is what he wanted to turn the traditional Irish music into.

Over 20 years after this, in the early 1840s, after the publication of his 1840 collection, Bunting started revisiting his earlier work. He went through printed copies of his 1797 and 1809 published books, and wrote in attributions and other information. These annotated books are now London, BL Add MS 41508. See Karen Loomis’s paper on them.

Against the piano arrangement of Ailí Gheal on page 2 of the 1809 book, Bunting wrote an attribution “Harp O Neil” (see below). He also expanded the printed title “Eilighe Gheal chiuin” by writing beside it in pen “me Carbhin” (there is pencil under-writing but I can’t read what that says – possibly the same, possibly ending in “l” instead of “n”). At the bottom of the page he writes “Probably the Eleanor O’Kirwan mentioned by Hardiman”. In his Irish Minstrelsy (1831) vol 1 p.278, Hardiman prints a poem titled “bEile N-i Chiarabhain” which begins “Taréir mo réime fo chríochaibh Fáil / ‘smo léirmhearda ‘nn-Eirinn tar aoíbhne chaích”; the notes on page 360 say that she was from Galway and that the song is by “the famous harper O’Carroll”. It seems to me that this song is in a different metre and has no connection to our song or tune. I think Bunting is getting very confused, and this is a good salutory lesson that he really didn’t have a clue about a lot of this stuff, and that he didn’t hesitate to fabricate or guess connections when he didn’t actually know.

Perhaps most interestingly from our point of view, Bunting has also gone through the music notation and has changed the line endings on page 2 (but interestingly not on page 3). He has deleted some notes and inserted others, to change all of the line endings in the first verse. He did not change the notation on page 3. He died in 1843, before he could finish this ambitious project to edit and re-publish his earlier collections.

I made a version of the 1809 typeset PDF score incorporating the changes to the music:

Other versions of our tune

There is a fragment of our tune in Edward Bunting’s 1802 notebook which he took to Mayo for his collecting tour with Patrick Lynch. I don’t know what this notation represents; whether he jotted it down there as an aide-memoir for the song that Lynch collected (see below), or whether it was inserted later. His title there is “124 Elli gheal ciun”. I don’t know what the number 124 refers to. It seems to require a B flat.

Donal O’Sullivan deals with our tune in his Bunting part 4 (JIFSS xxvi), 1932, p.1-4. O’Sullivan didn’t know about the live transcription notation on MS4.29 p.204, and so he works only from Bunting’s piano arrangements. He does, however, usefully list some other variants which we could look at to guide our understanding of how the tune curls.

O’Sullivan lists six different versions of this tune in Stanford-Petrie. These are tunes that Petrie wrote down based on his own collecting in the mid 19th century. I thought they were interesting enough to make machine audio of all of them for you.

Stanford-Petrie no.1111 is titled “Is truagh mé, gan mo ghrádh”.

Stanford-Petrie no.1162 is titled “Órán an uig” and has the note “From Mr. Joyce. p.71”

Stanford-Petrie no.1361 is titled “Henry! a ghrádh!”

Stanford-Petrie no.1414 has our title, “Eiligh geal chiúin” and the tag “From Frank Keane”. There is also an explanation of a deleted section in the manuscript, which my machine audio plays in its original place ignoring the deletion.

Stanford-Petrie no.1445 is titled “Ó ‘Dhia rú, a Sheághain!” with the explanation “O God John” and cross references to no.1162 above, and to Bunting’s 1809 published version.

Finally, Stanford-Petrie no.1574 is titled “Mo chreach is mo léan gan kitty agus mé” and has the tag “From T MacMahon”.

O’Sullivan also references Joyce 1909 p.25, which gives our tune under the title “The pearl of th’ Irish nation” along with two verses which I will discuss later .

The thing I notice about all of these versions of the tune is that they all have the fourth line as a repeat of the first, whereas Bunting’s transcription notation (and his derivative piano arrangements) have a fourth line that begins with the line 3 high motif.

Variants of this tune seem to be well enough known in Scottish and Cape Breton tradition, under the title “Pearl of the Irish nation”. You can hear a lovely 1956 field recording of Kate MacDonald singing the late 18th century song by Alasdair Mac Iain Bhain (Alexander Grant of Glenmoriston), “Oran an t-Saighdear” (the soldier’s song), which was apparently composed to this air. There is a text and translation of Grant’s song here at the Glenmoriston website. You can also hear a recording from c.1950 of Lauchie MacLellan in Cape Breton.

Song lyrics

We have already seen a couple of different song lyrics that go with this tune.

Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin tracked down the original song-poem in praise of Ailí Ní Chearbhaill (Ally Carroll), and she published the lyrics and a translation in A Hidden Ulster (2003) p.220-223, and subsequently also with a video performance on her Oriel Arts website. She explains that the song was composed by the poet, Séamus Dall Mac Cuarta in the late 17th or early 18th century, and says that it was composed for Ally Carrol, who married into the Hall family, perhaps a branch of the Hall family of Narrow-water Castle on the north side of Carlingford Lough. Mac Cuarta himself is said to have come from Omeath on the south side of Carlingford Lough. My photo at the head of this page is taken from above Rostrevor, looking south over the Lough to the hills above Omeath.

Séamus Dall’s poem begins “Atá lile gan smúid ar m’airese i Lú, Is ní cheilfidh mé a clú go dearfa”. The final line of most of the verses names Ailí Ní Chearbhaill.

Donal O’Sullivan had heard of Séamus Dall Mac Cuarta’s song (Bunting part IV, 1932, p.3-4) but he did not use it in his setting of Bunting’s piano tune; instead he found a different song in Patrick Lynch’s manuscripts from when Lynch was collecting song lyrics in Mayo in the summer of 1802. You can see Lynch’s neat presentation manuscript copy at QUB SC MS4.10.085, where he has titled it “An old song to the tune of / Eili gheal chiuin ni Cheárbhuill”. The song begins “Ta cruibh laga maodh is galanta gniomh / gan alta gan smaois gan feithibh”; it does not name the woman it praises but has a lot of Classical allusions. You can also see Lynch’s text with his facing-page English translation on QUB SC MS4.26.19i-l. Again the title is “An old song to <the> tune of / Eili gheal chiuin ni cearbhuill”. A different hand has added a title in pencil above the English translation, “Eli geal cuin ni Cear uil”. Another copy of this text in a differen (unknown) handwriting can be seen on QUB SC MS4.26.27. The title there is given in the margin as “Ally geal chiún ni chearbhuil”. Another untitled translation is in QUB SC MS4.14.1 104-5.

Joyce (1909 p.25) published a different song text (see above). He says “air and song from earliest memory” i.e. he has written it from his own repertory. His title is “The Pearl of th’ Irish Nation” and his text is in English, beginning “Though many there be that daily I see / of virtuous beautiful creatures”. He explains that these two English verses were composed by the poet Patrick O’Kelly at the beginning of the 19th century. You can see Kelly’s full text online at the NLS, probably originally published c.1790.

We have already mentioned Alexander Grant’s Scottish Gaelic song written to this pre-existing tune in the 18th century.

Bunting published the tune in 1809 with the early 19th century literary song by Thomas Campbell, beginning “A Chieftain to the highlands bound / Cries boatman do not tarry”.

It seems to me that the Séamus Dall Mac Cuarta lyric is the oldest song to this tune. What is not clear to me is whether the tune was composed for Mac Cuarta’s lyric. Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin cautiously suggests that “harper and fellow poet Pádraig Mac iolla Fhiondáin… may well have been the composer of some of Mac Cuarta’s song airs” (AHU p.223)

Titles

We have a whole load of titles for the tune, and for the lyrics, and I think it is worth listing them all. First, titles for the tune:

The title referring to Allie Carroll appears in two different variants of the tune, from Bunting and from Stanford-Petrie:

Alle ne hune ne Carolan (Bunting live transcription 1790s, added later pencil title)

Allié gheal chuin ni Chearbhuil (Bunting 1798 piano manuscript)

Eilighe Gheall Chiun / The charming fair Eily (Bunting 1809 published book)

Eiligh geal chiúin (Stanford-Petrie no.1414)

We have five other different titles from the different variants in Stanford-Petrie:

Is truagh mé, gan mo ghrádh (Stanford-Petrie no.1111)

Órán an uig (Stanford-Petrie no.1162)

Oran an avig (note on S-P no.1445)

Henry! a ghrádh!” (Stanford-Petrie no.1361)

Ó ‘Dhia rú, a Sheághain! (Stanford-Petrie no.1445)

Mo chreach is mo léan gan kitty agus mé (Stanford-Petrie no.1574)

It’s my suspicion that all of these five other titles refer in some way to song lyrics associated with our tune, but I don’t see them in either Mac Cuarta’s song, or in Lynch’s text. We have references to individual names, “Henry”, “Kitty” and “Seán”, which suggests to me that these might be different texts sung to the same or similar tune.

“The pearl of the Irish Nation” appears in the different variants of the tune, from Bunting and from Joyce:

The Pearl of the Irish nation (Bunting live transcription 1790s)

Pearl of the Irish nation (Bunting 1798 piano arrangement, 2nd title)

The pearl of th’ Irish nation (Joyce 1909)

and also as a generic title for the song air in wider tradition. The “Pearl” title is also used by Thomas Hughes when referring to the air for various English verses to be used in Bunting’s printed books; see QUB SC MS4.28 (Moloney, Intro & Catalogue 2000 p.332, 339)

The song poems also have different titles. We can ignore the Campbell one, since that was a deliberate confection for publishing purposes between Bunting and Hughes. Joyce gives us the title “The pearl of th’ Irish Nation”, but both the Lynch text and the Mac Cuarta text share variants of the title “Ailí Gheal Chiúin Ní Chearbhaill”. To me this suggests that “Ailí Gheal” might be a generic title for the tune. But I don’t know if that means the tune was newly composed for her, to go with Mac Cuarta’s song, or if an older tune was re-named because of its association with the song.

I don’t find reference to “the pearl of the Irish nation” in either Mac Cuarta’s song, or in Lynch’s text, though Mac Cuarta does say “Measaim nár bhéasaí sise ná an péarla, Ailí chiúin tséimh Ní Chearbhaill” referring to Ailí as a “pearl”. I am starting to wonder if it represents a different strand of the tradition, which may even be older than Ailí.

I find it interesting and significant that Bunting’s transcription notation on MS4.29 page 204 uses the Pearl title as its primary title. Presumably “The Pearl of the Irish Nation” was the title used by Bunting’s informant in the 1790s, who told Bunting this title and then played or sang the tune for him, so that he could write down the dots.

Attribution to informants

Petrie tells us who his tunes come from, but I have not chased these people. At the end of the day, all this is a huge digression for me, and my main aim is to understand the MS4.29 transcription notation which Bunting wrote down in the 1790s. As usual, Bunting does not give us any information on the MS4.29 page; there is no date, no location and no informant mentioned on that page, just the title and the music notation.

If we check my Old Irish Harp Transcriptions Project Tune List Spreadsheet, we can see that the live transcription notation of Ailí Gheal on page 204 sits in the midst of tunes which Bunting has copied from other books and manuscripts; some he has copied out of the Neal printed collection of 1724. So that doesn’t help us by giving a context in the form of a “group” of live transcriptions that may have been done in one session.

I don’t think that Ailí Gheal on page 204 was copied from a book or manuscript – it looks like live transcription dots to me. It seems to be in the form of dots expanded with note stems, and then overwritten with barlines and beams and alternate passages. All this is characteristic of Bunting’s live transcription writing.

Bunting later writes two conflicting attribution tags for the tune of Ailí Gheal. In his 1798 piano manuscript, squeezed into the bottom, he writes “From James Duncan County Down”. I don’t know when Bunting might have written this attribution tag in. He could have done it in 1798, as he was compiling this manuscript, only a few years after he had been out collecting from the harpers. But it is also possible that the attribution tags were squeezed into the bottom of these pages in the late 1830s or early 1840s, when we know Bunting was going through his older material adding contextual information.

In the early 1840s, after the publication of his 1840 collection, Bunting went back and added attribution tags to tunes in the 1797 and 1809 printed collections. Against the 1809 printed piano arrangement of Ailí Gheal, Bunting wrote “Harp O Neil”.

So did Bunting think that he got the tune from James Duncan, or from Arthur O’Neil? If we could be confident that the Duncan tag was written in 1798, perhaps we might lean towards him as the source. But I just don’t know. Duncan was from county Down, not far from where the Hall descendents of Alli Carrol seem to have lived, but I don’t know if that is significant.

I also think it is important to remember that neither Duncan or O’Neill played the tune in the form that Bunting presents it against their names. If either of them was his source, then it is only the live transcription dots on MS4.29 page 204 which is anything like what they were playing. The piano arrangements are a long way away from the traditional harp performance.

Many thanks to Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections for the digitised pages from MS4 (the Bunting Collection), and for letting me use them here.

Many thanks to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for helping to provide the equipment used for these posts, and also for supporting the writing of these blog posts.

This feels like one of the more important posts so far, in that it can serve as a starting point for others to go on those digressing paths to search for the people named, and also because there is so much that shows how much Bunting would change things around (especially if there are still people who doubt that).

Well-written, and gives much food for thought!

Amhráin Chúige Uladh has a song called “Hó! Ró! do bhuig a Sheáin!” collected from Counties Louth/Armagh about a Seán and his wig-related tribulations. Noting the alternate names in Stanford-Petrie, I wonder are Órán an uig, Oran an avig and Ó ‘Dhia rú, a Sheághain! all earlier versions of the same song? The tune in ACU is completely different, though. No connection with Ailí, apart from a geographical one.

Thank you, I don’t have that book (though I have just ordered a copy…)

Yes you may well be right, I would think it was fairly normal for titles and lyrics to share tunes like this. Do the words fit the S-P tunes?

They could be made to fit the second one, “Ó ‘Dhia rú, a Sheághain!” (1445), without too much effort (especially to a known variant of the chorus which has “Cúradh croí ar do bhuig” rather than “Hó, ró, do bhuig”). It doesn’t sound as suited to the “Órán an uig” (1162) one, but it could be done.