Karen Loomis suggested at her talk at Scoil na gCláirseach last week, that we try taking stereo pairs of photographs in the museums in Dublin on Tuesday. I am only just now starting to go through my pictures and see what I have. Here’s a first trial – grab your red/cyan goggles and see what you think!

Tag: organology

Playing position of medieval Gaelic harp

When I was in the National Museum of Scotland earlier this month, I was looking at the Queen Mary harp, and I noticed the wear on the lower back left corner of the soundbox. The corner of the box is quite worn away, and there is a wooden patch nailed on to the back of the box at this point, an old repair.

The wear on this corner was mentioned and drawn by R.B. Armstrong in his book The Irish and the Highland harps (David Douglas, 1904), though he talks mostly about sliding the harp along the floor when it was put down, Keith Sanger and Alison Kinnaird in their book Tree of Strings (Kinmor 1999), p.57 repeat Armstrong’s observations. Karen Loomis in her MMus dissertation (University of Edinburgh, 2010), p.49, includes a photo and a mention of this wear, but she is mostly concerned with the cracks from the repair patch nails.

I realised that the shape of this worn area is not just caused by general sliding of the harp, but instead it forms a flat surface which seems to me to be where the harp was stood on this corner when it was being played. You can see in my photo how the flat worn patch lines up with the projecting block of the bottom of the soundbox:

A long time ago I realised that if you sit on the floor to play a replica of the Queen Mary harp, then the harp naturally tips to rest on its projecting block and also this corner of the soundbox.

The angle of the flat panel therefore gives us a quite precise evidence for the angle that the harp was held at.

I propped my replica up on a hard surface, and adjusted the angle until my photo of my replica matched my photo of the original in the Museum:

And then, without moving the harp at all, I photographed the orientation of the harp, from floor level, at right angles to the plane of the strings, and also in line with it:

I think this gives a fair estimation of how the Queen Mary harp was positioned when it was being played.

Obviously there is some margin for error; the bottom of the projecting block would wear away and the corner of the box would wear away, so the angle in the front view would change over time. Also the flat worn surface is not entirely flat, but curves up towards the replacement piece. My positioning of the harp matches the most upright position. I would estimate that there could be 5 degrees either way since I was just doing this all by eye. The curving probably represents the harp being slid down to rest on its back as Armstrong suggests.

You’ll see that the strings are pretty much upright in the side-view photo.

The harp rests back quite a way behind its balance point. My replica won’t balance on that line between the box corner and the projecting block – if you tip it far forward enough to balance, it falls over sideways.

I looked again at Paul Mullarkey’s photos of the Trinity College harp. The soundbox is much more eaten away than the Queen Mary’s, especially at the bottom. However, the back bottom right corner of both the soundbox and the back panel are preserved, whereas the back bottom left corner is completely gone and is replaced now with extensive resin filler.

Silver strings on the Trinity College harp

I was browsing idly through a first edition of Grattan Flood’s The Story of the Harp in the Wighton Centre in Dundee the other week, when I came across the description of the Trinity College or Brian Boru harp on pages 41-42. An 18th century letter is quoted, giving some description of the harp:

It says “When given to Counsellor MacNamara, it had silver strings…”

The letter is said to have been written by Ralph Ouseley, who owned the harp in the early 1780s. Macnamara acquired the harp in about 1756. If this is true then it is an exciting and important piece of information both about the Trinity College harp itself, and also about the use of precious metal strings on the old Gaelic harps.

Now Grattan Flood is a notoriously unreliable author, and many of his statements can be proved false by laboriously tracking down the source documents to see what he says. Often he gives no citation or only a vage reference to “an old manuscript”. This section is given a citation though: “Bibl. Egerton, Brit. Mus., No. 74, p.351”

I contacted the British Library, and put in a request for a copy of this manuscript page. After some confusion and digging on the part of the librarians, (and a rather eye-watering fee on my credit card for their troubles) I was sent a high-res page scan of British Library, ms Egerton 74 f184. This page contains a transcription made by J. Hardiman in 1820, of the Ouseley letter, and Grattan Flood is vindicated – it really does say that the harp had silver strings on it. I was delighted that my expensive gamble in ordering the manuscript page had paid off – worth its weight in silver you could say!

So I wonder, what is the story here? Was the harp strung entirely with silver? Or did it only have a certain section of the strings left? I have seen a photo of an 18th century Irish harp (one of the Malahide / Kearney ones) which had all of its steel trebles on but none of its brass basses; brass being more valuable to remove and recycle I suppose. When were these silver strings installed on the Trinity College harp? There is no suggestion that the harp was played in the early 18th century; Arthur O’Neill in about 1760 implies that the instrument was not played for 200 years before then. Were these silver strings the remains of a 16th century setup?

The genuineness and authority of this statement from an 18th century owner of the harp makes me want to start experimenting again. How does it work to fit silver strings to the entire range? Can it be taken up to the high treble? What alloys work best for this? Ann Heymann tells me she has had a low-headed medieval Irish harp strung entirely in silver, but more experiments are needed!

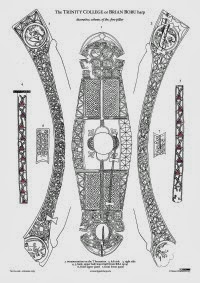

Trinity College harp decoration

A sneak preview for readers of my blog!

I have made a drawing of the forepillar decoration on the Trinity College harp. This has never been done before; when R.B. Armstrong studied the harp for his 1904 book, he did not draw the pillar decoration, saying it was probably later work. And no-one has done a good published study of the harp since then.

I have been admiring the pillar decoration on my vists to Dublin for a few years now, and I managed to get enough closeup photos to be able to work out almost all of the decoration. I have drawn it all out schematically, following the general principle of Armstrong’s superb diagram of the decoration of the Queen Mary harp forepillar.

I very much enjoyed doing this work; the decoration is really complex and busy and it was a real challenge to trace the twists and turns of each vine stalk and interlace strap.

I’m publishing the drawing officially on 1st October, both as a free PDF download that you can get from the Trinity pillar decoration webpage and also as a 2-colour A3 sized digital print on good art paper that you can order from the Emporium prints page.

Be sure to read the rest of the Trinity pages as I have added some other interesting information and illustrations.

Harp bags

I was asked very recently about the historical evidence for old harp bags, and so I dug around and found a half-finished project to write up what references I have found so far. Today I finished it off and you can now see it at

http://www.earlygaelicharp.info/bag

Spitzharfe or Arpanetta

I have a spitzharfe on loan, so here is my first feeble attempts at playing a tune on the thing!

I have written up my researches into the instrument and its history and you can read my article on my website at www.simonchadwick.net/spitzharfe

strange brass rod

In the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, there is a little wooden box containing three brass or bronze tapered pins. The left and right hand ones are tuning-pins for early Irish harps, but the middle one is a mystery to me. It is labelled and described as a harp tuning pin but this is clearly rubbish – its tapered shaft is hexagonal and its wide end is in the form of a female bust with stubby crossed arms and bare breasts.

I really can’t think what this thing is!

I have looked at it on and off for about 10 years; I kept asking Hèléne La Rue if we could get it out and look at it but we never got round to it. But here’s my recent photo.

Some thoughts on replicas of old instruments

To me the extant surviving instruments are like treasure-houses of detailed specific data about not only the historical instrument design and construction, but also about all other aspects of the historical music-making (because of the presumption that the original instruments were commissioned by discerning musicians).

So I would regard every last detail about the old instruments as having something important to tell us. And as a player investigating the old music traditions, I want a replica harp that is as close as humanly possible to the old museum examples.

Of the two oldest Gaelic harps, the Queen Mary and the Trinity College harp, I would say they are remarkably similar in design and construction, and that similarity points to a shared conservative instrument-making tradition and a shared conservative music-making tradition, covering Ireland and Scotland. Similarities between them I take to be confirmation of that shared tradition; differences between them become specific individual features of that particular instrument. (you can do the same exercise with the later harps but there are more differences then. The Trinity & Queen Mary are by far the most similar pair I would think).

The Queen Mary harp is far easier to consider since a lot more info has been published on it, mainly the study in 1904 by R.B. Armstrong and more recently Karen Loomis’s ongoing study of it which is published in interim in the Galpin Society Journal 2012. The Trinity College harp is far less well studied or published; the information in Armstrong’s 1904 book is a lot more sketchy and has as I understand it at least one misleading error; and there has not been any further more recent published work than that.

When I commissioned my own harp (which is a copy of the Queen Mary harp) I insisted that my maker simply copy every aspect he could see with as much fidelity as possible, from selection of timber through to decoration and even the idiosyncracies of individual fittings and adjustments. The idea being to end up with a new instrument that was as close as possible to handling the real thing in as many respects as possible. Since then, Karen Loomis’s work producing 3D X-ray models of the instruments and materials analysis, has revealed important structural and decorative information that would have led to some different decisions being made with my copy, but that is part of the learning process, and Karen’s study has directly addressed certain questions which were raised by my commission.

When I commissioned my own harp (which is a copy of the Queen Mary harp) I insisted that my maker simply copy every aspect he could see with as much fidelity as possible, from selection of timber through to decoration and even the idiosyncracies of individual fittings and adjustments. The idea being to end up with a new instrument that was as close as possible to handling the real thing in as many respects as possible. Since then, Karen Loomis’s work producing 3D X-ray models of the instruments and materials analysis, has revealed important structural and decorative information that would have led to some different decisions being made with my copy, but that is part of the learning process, and Karen’s study has directly addressed certain questions which were raised by my commission.

When I worked with David Kortier on the HHSI Student Trinity Harps, this was a somewhat different project. The initial aim here was simply to obtain a set of affordable harps for use in summer school classes. We were not satisfied with any commercially available models so we approached Kortier to discuss options and he ended up making a custom student model for the Historical Harp Society of Ireland. The main design criteria for this student harp were that it be affordable and quick to make, but that it present a student in class with the string count, string spacing, ‘feel’, and overall ergonomics of the original harp. So you see there was no attempt made to reproduce the subtleties of construction or decoration; but from the beginning the exact geometry and ergonomics of the strings were the most important thing. This was so that a class student given one of these harps would instantly be learning the finger movements and playing techniques exactly as on a proper replica (i.e. exactly as on the real thing!), even if the nuances of sound and response were not as accurate as could be obtained by a proper replica.

We based the first HHSI Student Harp on the Trinity College harp because it is the Irish national symbol and this seemed appropriate. Kortier had visited Trinity College and inspected and measured the original some time before, so he was able to use a lot more than just the published data; even so there were a number of details that had to be guessed or interpolated simply because the data about the original is not available. I mean the data is there, it exists, but it is locked away inside the fabric of the instrument itself and would need a long term detailed programme of scientific analysis like is happening in Edinburgh, to discover it.

So in summary, reconstructing an instrument from the surviving old instruments really needs a partnership between high-tech scientific analysis of the original, and a highly skilled sensitive craftsman-artist. In practice, you have to compromise and make do with what you can get – most of the compromise to date being on the analysis side I have to say. I hope that the recently published ongoing work in Edinburgh will soon feed into the work of the artist-craftsmen and we start to see really high quality accurate replicas that take on board and accurately reproduce these important new discoveries about the detailed features of the old harps.

Every level of data is vital – from the large scale measurements of height, width, string count and string lengths etc, down to tiny details of alignment and adjustment and profiling, all combine to give a very particular playing experience of the musician with important implications for what is and is not idiomatic for that particular instrument – and as our mission is to rediscover the lost old historical idiom, it seems to me that the idiom of each specific historical instrument (or rather, the imperfectly recreated idiom of each attempted reconstruction) is a vital tool for this. And that means that each reconstruction has to be as close as humanly possible to the specific museum original to have any value in that process.

New harp makers

I’m always interested to encourage instrument makers who are looking to start building good copies of the medieval Gaelic harps, and recently I have heard from two established instrument makers who are branching out into early Gaelic harp territory. Both have chosen the Queen Mary harp as their model – a good choice given the amount of information published about it, especially since Karen Loomis has started publishing her researches now (see Galpin Society Journal, 2012)

Michael King is an instrument maker in England, specialising in lyres, kanteles and related instruments (I have one of his lyres). For him the Gaelic harp is a step up in size and complexity but the completed instrument looks very handsome I think:

More info from his website.

Pedro Ferreira is a Portugese instrument maker who produces exquisite clavichords and other baroque instruments. His Gaelic harp is also based on the Queen Mary harp; this is a slightlier simpler prototype I think. I am very excited to see a luthier with this amount of experience on sophisticated historical instruments turn their attention to our harps.

You can get more from his website or from his Facebook page.

As yet I have not seen either of these instruments in person, and I have not had a chance to play them or listen to them. Both of these harps have followed my ‘student’ stringing regime with brass in the treble and mid-range and sterling silver in the bass. I am sure both of them would benefit greatly from having gold strings in the bass instead of silver!

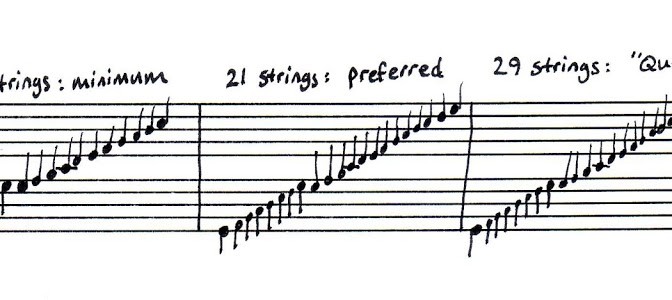

Range and gamut of small harps

Discussing what is a suitable extra-small harp for a child (extra-small for both ergonomics of a child’s size, and also to make it cheaper to purchase), the question of the range of the instrument came up.

I think that the medieval gamut, from bass G up to treble e, is an important factor in thinking about the old music. It makes little sense to me to cut off the bass of the gamut only to add in extra treble strings above this, yet this is what many modern harp makers do.

The gamut (including the doubled sister strings) takes 21 strings (centre chart). If you need less than this, then cutting off the bottom as well as the top makes sense. To play Burns March, one of the key beginner tunes, in the usual position, requires from bass c up to treble a, 14 strings including the sisters. Add two more in the treble to get 16 covering 2 octaves (left hand chart).

I would set up a replica of one of the extant medieval Irish and Scottish harps as shown in the right hand chart. The extant continental medieval harps tend to have 26 strings, i.e. 3 less in the treble.

There’s more technical discussion about historical range and gamut on my other site