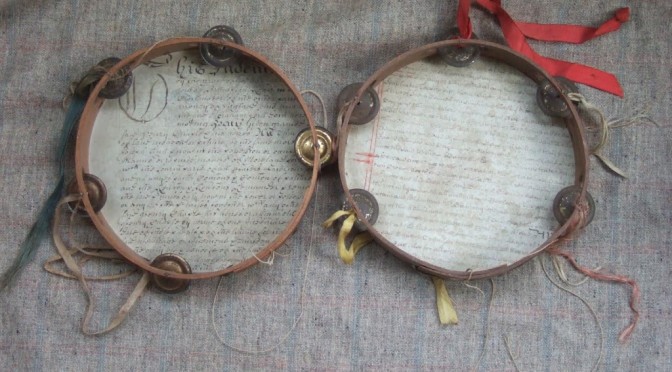

I have recently finished setting up an Irish lyre for a customer. This is my own speculative setup. The design is based on a generic Northern European early medieval lyre like the surviving historical instruments from Sutton Hoo in England or Trossingen in Germany, but I have strung and set it up using stringing principles from the historical and mythical Gaelic sources from Scotland and Ireland. The aim is to produce the type of instrument that you can see on the Clonmacnoise high cross, or the type of thing that might be described as cruit or tiompán in early medieval Irish texts.

Following medieval Irish and Scottish Gaelic practice, the strings are made from metal – in this case silver, latten (copper alloy) and soft iron. The instrument is tuned to a hexachord (g-a-b-c-d-e) and has a bright, open voice. The body of this instrument is an inexpensive import, but it is nonetheless a competent piece of work with a hollowed-out maple soundbox and a solid maple soundboard.

For this particular instrument, my customer asked for a reconstruction copy of the Skye lyre bridge fragment, discovered a few years ago in Uamh an Ard Achaidh (High Pasture Cave) on the Isle of Skye in Scotland. This broken lyre bridge dates from the iron age – one thousand years earlier than the surviving English and Continental lyres, but clearly showing the continuity of the lyre tradition in Northern Europe. I carved this bridge entirely by hand from some lovely local figured maple.

If you are interested in commissioning an early Irish lyre, whether an affordable imported student model like this or a full-specification professional model by a British instrument maker, or if you are interested in having a copy of the Uamh an Ard Achaidh lyre bridge, please get in touch with me and we can discuss the options!