I was up in Aberdeen yesterday, interviewing for an education project themed around the Deskford carnyx. As part of my preparation I was reading up on the Deskford find as well as on carnyxes generally, and some ideas crystallised in my mind about this object specifically, as well as about the whole theme of reconstructing archaeological objects more generally. And the recreation of ancient music is perhaps the most difficult strand of reconstructing ancient objects, because the musical instrument is not merely a decorative item or a functioning tool, but is the living substrate of a whole other creative art, i.e. music making.

I was chatting with Maura Uí Chróinín in Kilkenny, about the “BC/AD” music-archaeology theme of this year’s Galway Early Music Festival, and she made the point that most music archaeologists seem to work on their own, outside of both the musical and the archaeological mainstream. The reasons for this are obvious enough, since archaeologists most often don’t have music training and musicians don’t have archaeological background, and so the majority of scholars on both sides feel un-qualified to judge or participate in music-archaeology work.

The late Iron age object from Deskford (my photo shown on the right, in the NMS) was excavated in the 19th century and so is, by modern standards, poorly recorded and conserved. It is in the form of a sheet bronze hollow boar’s head, and has with it a number of associated sheet bronze items which seem to form the palate of the boar’s mouth, its lower jaw, and a circular plate which is often assumed to have closed the open back of the head. The original descriptions also mention a wooden tongue mounted on springs but these are lost.

Early suggestions of its function were perhaps as a headdress. In 1959, Stuart Piggot published a paper suggesting it may have been the bell of a distinctive type of Iron Age long trumpet, called carnyx. At that date, the carnyx was known from classical art and literature, and Piggot drew attention to a lost example excavated in Tattershall, England, in the 18th century.

Piggot’s article included a speculative reconstruction of the Deskford boar’s head mounted on a long vertical tube, and despite his reservations and cautions, this image and the idea of the only extant carnyx surviving from North-East Scotland captured the public imagination. In the 1990s, John Purser led a team to build a working reconstruction of the boars head as a long trumpet bell, following Piggot’s drawing. This modern carnyx has been played extensively by trombonist John Kenny – I remember seeing him play it at a concert in Edinburgh some years ago.

In all this excitement, people forget that Piggot’s suggestion was just that – a speculative suggestion made at a time when very little was actually known about the carnyx. Now we have a lot more information available, especially since the publication of detailed information of the set of almost complete carnyxes excavated in 2004 in Tintinac in France. Looking over the depictions, the Tintinac examples (illustration left from Wikipedia) and the River Witham drawing publiushed by Piggot, I see a number of important features that could be said to characterise the carnyx. The tube is tapering along its whole length like a horn, and flares gently but markedly towards the animal head, which is not seperate in shape but forms a smooth continuation of the bore flare. The animal mouth is wide open, not constricting the bell of the instrument. In contrast, the Deskford head tapers the other way, severly constricting the bell of the reconstructed instrument – a recent acoustical study notes that it acts like a “trombone mute”. Also, the use of the circular dished plate to close the back of the boar’s head requires a thin tube, with a sudden step in profile as the tube meets the head. Again this has an adverse effect on the harmonicity of the instrument in contrast to the smooth expansion of the other extant and depicted carnyxes.

These considerations alone make me instantly very suspicious of this idea, that the Deskford head represents the remains of a musical instrument. I can see no specific evidence to support this interpretation and I can see a number of problems, ways in which the Deskford head is markedly different in form from all of the other extant and depicted carnyxes. I would go as far as to say, the Deskford boar’s head is not a carnyx.

A number of descriptions of the reconstruction Deskford carnyx are at pains to point out that it involves a large amount of interpretative or newly-invented design, but that nonetheless it represents a fascinating working instrument that can “result in

instruments capable of playing a valuable role in the musical culture of the present day.” (M. Campbell & J. Kenny, Acoustical and musical properties of the Deskford Carnyx reconstruction, Proceedings of the Acoustics 2012 Nantes Conference). This is the rub – you invent a new instrument, give it an ancient name and hang it on an ancient cultural icon or artefact, and so set off in a new direction. This is not music archaeology; this is modernist cultural creativity, re-imagining ancient symbols for new purposes. If the purpose was really to get the ancient carnyx up and running, then there are the Tintinac examples ready to be exactly replicated; compared to that, a new instrument using a copy of the Deskford boar’s head as its bell has virtually no archaeological or music-archaeological value. Clearly it is not intended to do music-archaeology work; instead it is designed and produced for present day national-cultural reasons, to provide a newly-invented iconic “ancient” Scottish sight and sound.

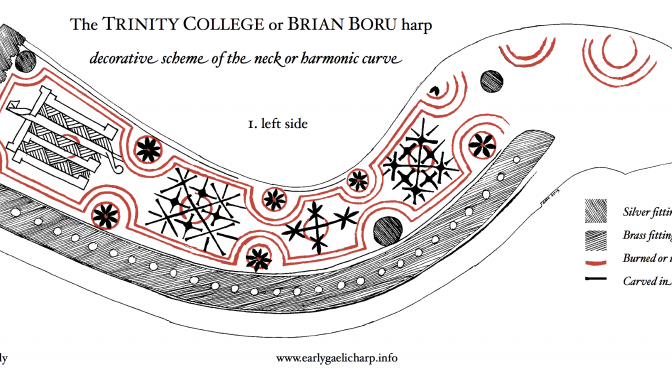

We are not so far away from the invention of the gut-strung lever harp in the 1890s, and the neglect of the historical Gaelic harp…

One final thought: many modern depictions or recreations of carnyxes emphasise its long S shape, with a vertical tube topped by a 90 degree bend to hold the animal head, and with another 90 degree bend at the bottom to hold the mouthpiece horizontal while the tube is vertical. It seems to me that all the ancient carnyxes did not have this 90 degree bend at the bottom – some may have had an oblique mouthpiece cut in the lower end of the vertical tube, but the normal arrangement seems to have been a plain mouthpiece on the end of the long tube, as seen on the Tintinac example illustrated above. So the player has to tip their head right back and blow almost vertically into the instrument. A very different playing position with all its implications for sound production!