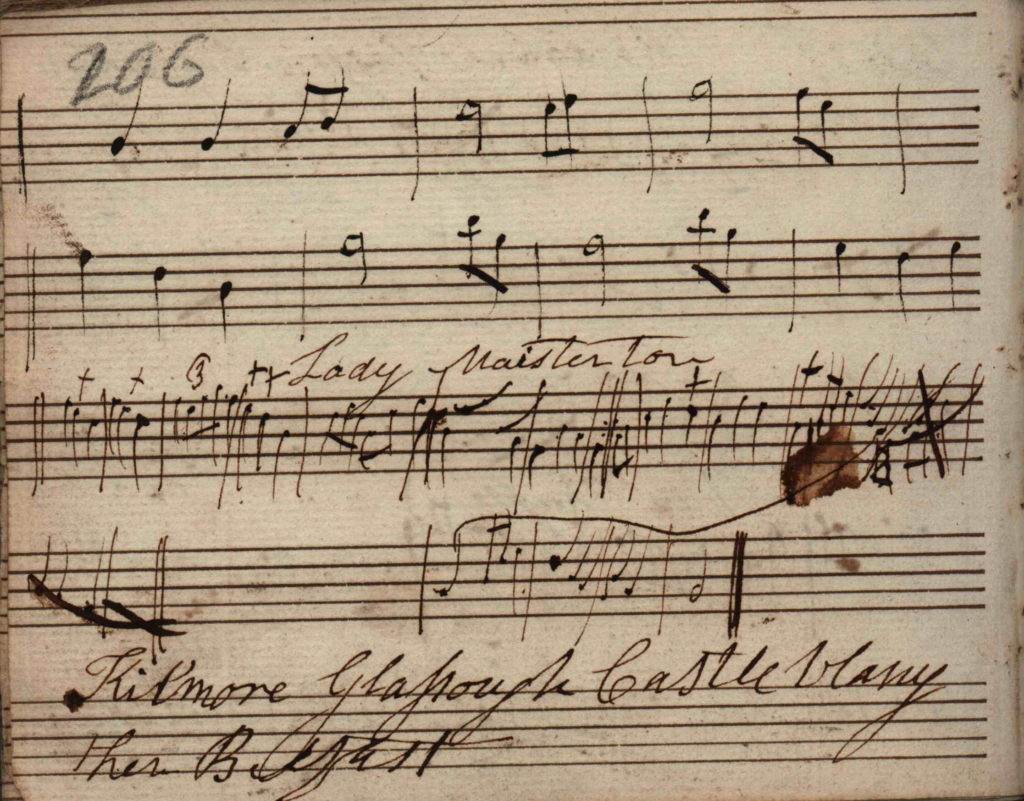

There is what looks like a live transcription of the tune of Lady Maisterton, in the middle of a load of material copied from printed books into Edward Bunting’s collecting pamphlets, at Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.29 page 206/204/213/f101v.

This section of the manuscript starts on page 201, and there are a number of interesting harp tunes on pages 201-3 which I used to list as transcriptions, but which I now think show signs of being copied from other written sources: Planxty Reynolds, Bumpers Squire Jones, Caitlín Ní Uallacháin, Charles Coote, and Madam Sterling. The significant features that make me think they are not live transcriptions include being in non-harp keys; having minims, pause marks, 1st- and 2nd-time bars. You can check my Tune List spreadsheet and my MS29 transcript PDF for details of all these pages and items.

On pages 205-207 and 209 are tunes and text coped from Neal. And on page 206 there is a neat copy of the tune of Have you seen my Valentine, presumably copied from a book or manuscript.

In between these copies there are a handful of transcriptions which look like they may have been inserted into spare spaces.

On page 204 is a very interesting transcription of the song air of Ailí Gheal, but I am not going to do that since Sylvia Crawford is working on it. You can listen to her with Pádraigín Ní Uallacháin at Oriel Arts (that was done before I identified this transcription). On page 206 is the live transcription of Lady Maisterton, which I will address in this blog post. And on page 208 are two tunes titled “Callena vacca” which I think I may do next after this.

The transcription

You can also download my PDF typestting of the tune, used to generate this machine audio.

There are a few erased and re-written notes in the first half. The transcription gets a bit hairy towards the end, but Bunting has helpfully re-written the final 4 bars to show us what is going on there. There is no key signature or time signature, though it is clearly barred in 3/4 time.

Bunting has written a repeat mark at the end of the first half. Do we understand this to be a proper repeat of the first half, or just his use of the dots as a section break? Are there slightly obliterated forward-facing dots there too? It is hard to say, but in any case there is no closing repeat mark at the end of the tune. My machine audio repeats the first half but not the second.

Bunting has written + signs above a number of the notes. What does this sign mean? Sometimes I suspect it is just an ornament or articulation sign; other times I wonder if it is some kind of code for a bass bump or doubling. I think we cannot tell much more than that “something is happening” at that point in the transcription.

At first I thought I could see a “B” written in the 4th bar of the second half but I am less certain now. This is the horribly messy part of the notation where Bunting has completely screwed it up. Why, by the way, does he so often get things so wrong? It seems such a simple wee tune – why does such a competent musician struggle so much? I suspect that the style of the harpers was just too alien to the classically-trained Anglo urban Bunting, that he just couldn’t make out the rhythmic nuances of the traditional harp performance.

Later piano arrangements

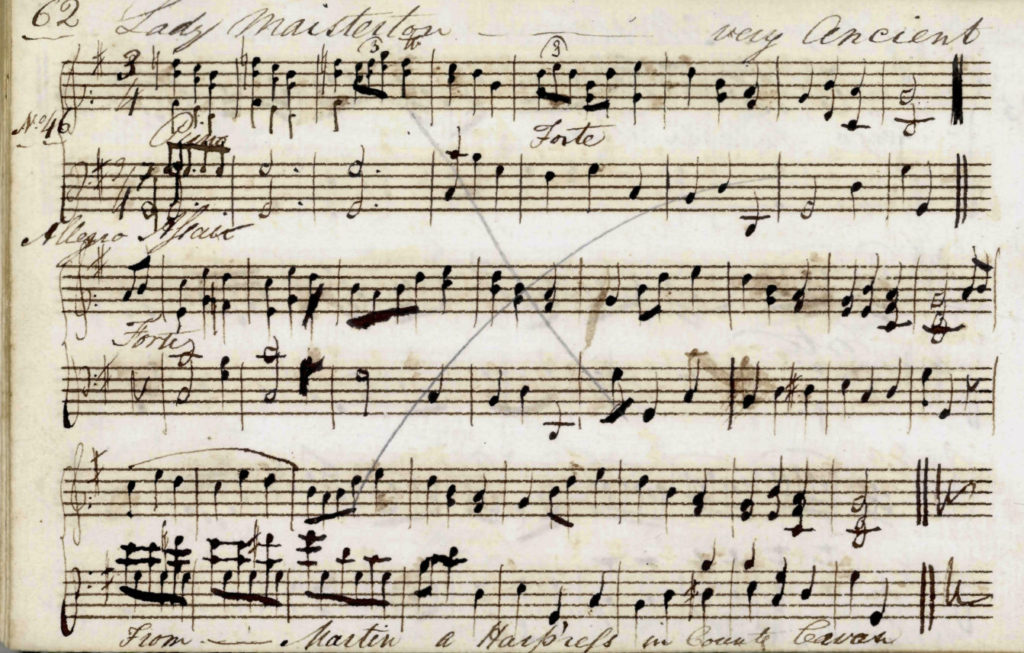

In 17978, Bunting made a piano arrangement that is clearly based on this transcription. It is in his unpublished “Ancient and modern” piano manuscript. It is titled “Lady Maisterton – very ancient” and is tagged “From ___ Martin a Harp’ress in County Cavan”

We can safely ignore all of Bunting’s piano bass and arrangement and harmony, as that is entirely a product of his Western classical keyboard upbringing and training, nothing at all to do with the old Irish harp tradition.

But there are a couple of interesting and important points in this notation. One is that he explicitly marks the key signature with one sharp, to indicate that the tune is in G major. But he also cancels every single F with a natural sign, putting the tune in G major with a flat 7th. I have therefore used f naturals in my typesetting of the transcription and my machine audio above.

The other interesting thing about this 1798 piano arrangement is that he writes the first half of the tune once, with a double bar line at the end; and then he writes the second half of the tune out twice fully.

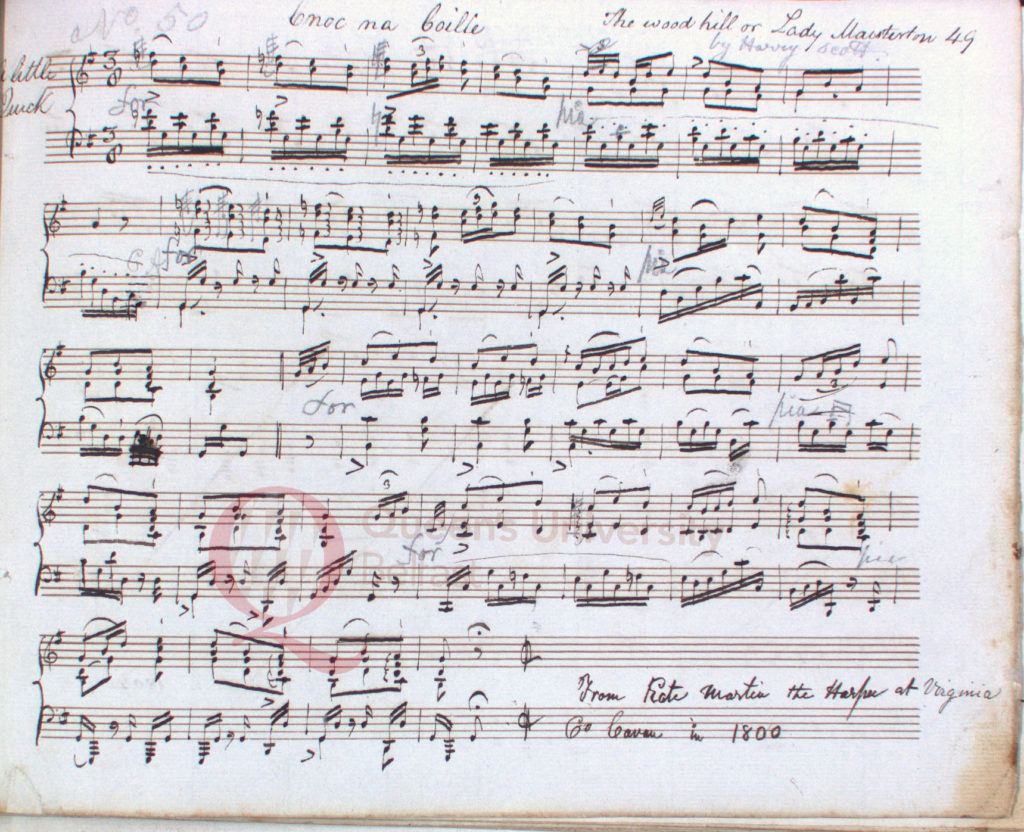

There is another piano arrangement which was made in the 1830s, as part of the preparaions for the 1840 publication. I think this is not in Edward Bunting’s hand and has emendations and changes in another hand. The title is “Cnoc na Coille / The wood hill or Lady Maisterton” and there is also a pencil addition that reads “by Harry Scott”. At the bottom it says “From Kate Martin the Harper at [Virginia] Co Cavan in 1800”. The place-name “Virginia” seems to have been inserted later.

This piano arrangement expands the structure of the tune by writing out both halves twice. The arranger or editor of this version clearly was unable to cope with that prominent flat 7th and so they changed all the accidental f natural signs back into sharps.

There is another similar piano arrangement in the companion piano volume from the 1830s, QUB SC MS4.13, but I haven’t seen that page.

Bunting published this tune as no.9 on p.8 of his 1840 collection. Again, both halves are written out twice fully. The index says “The woodhill, or Lady Maisterton – author and date unknown – C. Martin, harper, at Virginia – 1800”. Thankfully, the f sharps of the ms27 arrangement have not been used, and the fs are all marked natural.

Other versions

I haven’t found any other versions of this tune, except for post-1840 publications that have simply copied or developed Bunting’s piano arrangement.

Composer

First, the composer. The pencil attribution to “Harry Scott” in MS4.27 is quite a surprise, though it is also of interest that Bunting drops this attribution a few years later in the 1840 print, and says “author and date unknown”. I discuss the Scott brothers in my post about Peigí Ní Shléibhín. Harry Scott’s brother John is said to have composed Scott’s Lamentation; Could this explain why Bunting has doodled “Maisterton” on the pages where he was collecting Feachain Gléis and Scott’s Lamentation from Denis O’Hampsey? Does this Harry Scott attribution mean we should be looking for a person called Lady Masterton in the first half of the 17th century? The Scotts are associated with Tipperary, Munster, and also Westmeath.

Titles

In the transcription perhaps 1796, Bunting titles the tune “Lady Maisterton”. The 1798 piano arrangement uses the same title. It’s not until the 1830s that the title “Cnoc na Coille / The woodhill” becomes attached to the tune. Is this an error on Bunting’s behalf? Is “Cnoc na Coille” an unrelated tune title / song air? I think that Bunting or his editors sometimes did conflate multiple titles, putting tunes out there with unrelated titles which can unfortunately stick.

Bunting has written the title of our tune around the neat copy of Denis O’Hampsey’s performance of “Feaghan Gleas” on QUB SC MS4.29 pages 56–57, and also the start of Scott’s Lamentation on page 58. Bunting writes “Maisterton” or “Lady Maisterton” eleven times on those three pages.

The title also appears on page 218, apparently unrelated to the tunes of Bonny Portmore and An bile buadhach. The text at the bottom of that page is part of a stanza of An bile buadhach; but the the text relevant to us is in the middle and reads “Anthologia Hibernia Maisterton Anthony / Maisterton a real old Irish / Tune”. But I don’t understand these. I don’t find any references to Lady Maisterton in Anthologia Hibernia (4 vols, 1793-4) but I confess I have not read all 2000 pages closely.

Bunting’s doodles are a kind of crazy psychadelic world of their own and they would be worth an in-depth study in their own right.

There are lots of different unrelated families with similar names. The most common Irish spelling variant is Masterson – Mc Master – Mac an Mháistir which seems to be mainly from the border areas between Cavan (Ulster), Longford (Leinster) and Leitrim (Connacht). Or could we look for a family such as the Mastersons of Ferns in county Wexford? Sir Richard Maistorson of Ferns (1545- 1627) married Joan Butler, who was daughter of Viscount Mountgarret and related to the powerful Butler earls of Ormonde. Could she be our “Lady Maisterton”? More research is needed.

Attributions, dates and places

Bunting says he collected this tune from Kate Martin. She was an interesting character, a woman harper in the later 18th century, at a time when it was mostly a man’s world. Bunting says or implies that he collected the tune from her at Virginia, but I am not sure if this is true. I added Virginia to my map on my collecting tours blog post, but I wonder if Bunting is really saying that he collected it from her at an unknown place, and, by the way, that she was from Virginia.

Also the date 1800 doesn’t make sense, seeing how we have the piano arrangement in ms4.33.3 apparently done in 1798. I really suspect some of these names and dates may be just made up to add colour to the piano arrangements.

So is the ms4.29 p.206 transcription done from the playing of Kate Martin? Presumably in 1796?

I don’t know that much about her. Arthur O’Neill is our main source; he writes in his Memoirs (QUB SC MS4.14 p.89):

Kate Martin, this female performer was born in the parish of Lurgan in the County of Cavan. Her parents I am informed were but poor. I do not know how she became nearly blind, as she could walk without a Guide. She was taught the Harp by a man named Owen Corr, with whom I had no acquaintance. Kate played very handsomely, but had a strong partiality for playing the tunes composed by Parson Sterling, the Rector of that parish of Lurgan, who was celebrated for his performance on the Bag pipes This Minister compos’d a celebrated tune called the “Priest of Lurgan” which tune Kate played uncommon well. She seldom or ever travelled out of the bounds of the County Cavan.

For more info about Parson Sterling and Kate’s connection to him, see Seán Donnelly’s article “An eighteenth-century minister and piper”, Ulster Folklife 46, 2000.

Kate travelled to County Longford to attend the 2nd and 3rd Granard balls in 1785 and 1786, but she didn’t go to Belfast in 1792. Bunting has tagged a few different tunes from her in later piano arrangements, which you can see on my tune List spreadsheet. But this is the only transcription that I think might be associated with her.

More work needs done on Kate Martin.

At the bottom of the page, Bunting has written “Kilmore Glaslough Castleblany / then Belfast”. My interactive map shows these places, as well as Virginia. Could this be a proposed itinerary for leaving Virginia and travelling home? Maybe not. Unfortunately there is more than one place called Kilmore in the general area so this is not a particularly satisfactory map.

Song words

Patrick Lynch collected the words of a song titled “Cnoic na Coille” from a traditional singer, apparently on his tour to Mayo in 1802. Here is the text, from QUB SC MS4.7.272

Cnoic na Coille

Nach mise an caingean eanraic

ar a taobhsa do chnuc na coille

mar bhiodh Oisin a ndeigh na feine

agus a teag ag a shior sporabh

biom ag osnaoil agus sir eagcaoin

agus sior ghuil thri mo colladh

nuair shaoiliom la bhe ag eirighigh

ni leir liom e le fir thuirse

Noirin a mhile stoirin na biobh

brón ort no fír thuirse

go siubhalainn a dhamhain mor leat

ga boeallach na maoin eallaigh

Se do chomhradh le gach oigfhear

do mheadaigh ar mo ghuinse

& ma ni tu nios mo e

toigear moran da mo ghean diot

Se dubhrais tri huaire leis a staidbhean

agus dirim

gurab iomdha maighdhion og

bhi mo dheighse le fada

Ta gradh na mban og

an mo chonrasa taisgidh

a mbrollagh mo leine

agus an aenteach le manam

Lynch’s English translation is in QUB SC MS4.32.247, titled “the wood hill”

Cnoc na Coille – The Wood Hill

I am like a lonely Barnickle

on the side of the woody hill

Or Oisin after the fenii

whilst death was always threatening him

Still sighing and lamenting

and groaning through my sleep

and when the morning light arives

I can scarce perceive it with heaviness

Nora my store of thousands

do not grieve nor live in sadness

I wd travel the world over with you

regardless of cows or cattle

It was your conversing with other young men

that gave increase to my trouble

and if you do it any more it will take away

a great part of my love for you

I told it three times to this fair maid

and I repeat it again

that there is many a young virgin

has sought for me this long time

The love of the young maids

I conceal within my chest

within the breast of my shirt

and in the recess of my soul

I don’t think that these words fit our tune, at least in the form we have it in. Do we understand there to be a connection between “Lady Maisterton” of the tune title, and “Noirin” or Nora of the song? Or is the title match just a co-incidence? Bunting also publishes a different tune titled “Nóirín mo mhíle stóirín” about Nora (1840 p.24). More work needs to be done on this. At the moment my suspicion is that these words do not go with our tune.

Many thanks to Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections for the digitised pages from MS4 (the Bunting Collection), and for letting me use them here.

Some of the equipment used to create this blog post was funded by the Arts Council of Northern Ireland.

Frank Bunting, ‘Edward Bunting (1773-1843) – Resolving his family background. Part 2: the Quin side’, in Dúiche Néill, Journal of the O Neill Country Historical Society, No. 25, 2018, discusses how Edward Bunting had Taylor cousins around Kilmore near Loughgall in County Armagh, so perhaps it is that Kilmore rather than the Co. Monaghan one that he is referring to in his list.

Joyce published a different version of this tune in his Old Irish Folk Music and Songs (1909). Our tune is no.717 on page 358, titled “The woody hill”. Here’s a PDF typeset version and machine audio.

I’ve long been interested in this piece, and to me the structure/melody has a majestic flavor of some of the earlier harp songs… maybe even Cumha Caoine Albanach. Fortunately, my print out of the mss. version (from microfis) have me something to work with, but these color digital images show SO MUCH more. Thank you for getting Queen’s to release some of these more important pieces, Simon!

Thanks Ann, yes I agree the structure of the tune fits it into that earlier group.