Burns’s March is one of the first tunes taught to young harpers. In this blog post I am going to describe the live transcription notations that we have from Irish harper tradition-bearers in the late 18th and early 19th century. Then I will try and find derived works that give us contextual information and attribution tags. And finally I will look at some independent versions or variants in other sources.

The live transcriptions

As well as the two live transcription notations of the tune, taken from two different harpers at two different times, we also have what I think is a live transcription of song words, likely also taken from the dictation of a harper tradition-bearer. Lets look at each in turn.

The 1790s live transcription

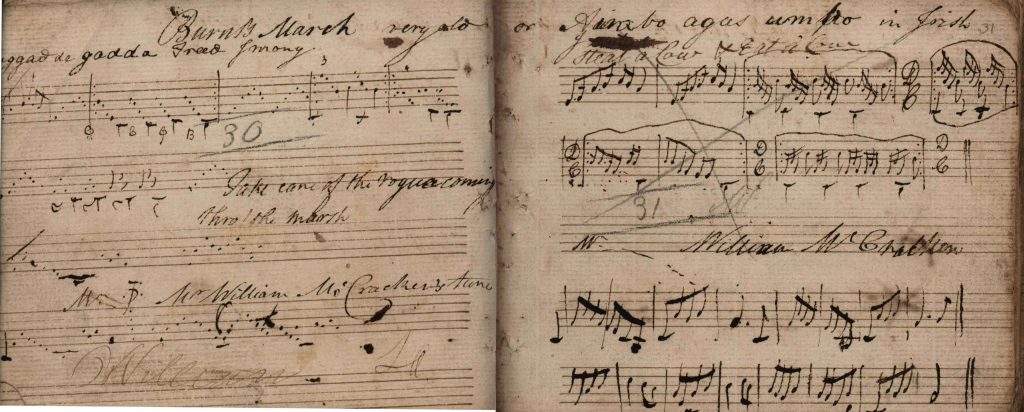

Edward Bunting made what looks like a live transcription notation of Burns’s March from the playing of an old Irish harper. This was done some time in the 1790s. We can see the live transcription notation on two facing pages, now bound up into Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.29, pages 30/30/039/f14v and 31/31/040/f15r.

Burns’s March occupies the top two staves on both pages. The lower half of both pages is taken up by a different unrelated tune, titled “Mr William McCracken’s Tune”.

On the left, page 30, is the live transcription dots, which look like they were written at speed as the harper informant played. Then on the right, page 31, is a neat copy, which fleshes out the rhythm and structure of the tune.

Bunting has written loads of titles. Across the top of both pages he writes “Burns’s March very old or A[im]bo agus um[b]o in Irish”. Then on page 31 he writes “steal a Cow & Eat a Cow”. On page 30 he writes a different title and translation: “huggad de gadda freed smony / Take care of the rogue coming / thro’ the marsh”

Both of these notations are written one note higher than what would be a sensible harp key, and so my PDFs and machine audios bump them one note down.

I think you can see that both of these versions are quite difficult to understand, because the notation is crammed into the space and the notes sometimes overlap. We can obviously look at later piano derivative versions but there is the danger then that Bunting himself may have neatened and regularised his own corrupt transcription notation.

On page 30, there really is not any useful rhythmic information. Page 31 does have rhythmic beaming, but the note values don’t always add up properly and there are still sections where the notes are piled on top of each other.

Bunting has used dotted bar lines to indicate repeated sections in the p.30 transcription dots, but my machine audio does not play these repeats. On p.31 he uses both repeat bars, and “D.C.” markings, and my machine audio follows these.

Other people have written commentaries on these two pages; I did myself in my book Progressive Lessons (2017). Ann Heymann writes a commentary on these two pages in her article ‘Three iconic Gaelic harp pieces’ in Harp studies, ed. Sandra Joyce & Helen Lawlor, Four Courts, Dublin, 2016. And Siobhán Armstrong has looked at this version of Burns’s March as part of her PhD thesis.

From the point of view of my old Irish harp transcriptions project, I don’t have that much to say about these two pages. Both notations seem very confused, and to get anything musical out of them we would have to either use a lot of creative imagination, or look at other versions of the tune.

Live transcription song words

We have some words which seem to go with this tune. I wrote a post about the words back in 2017. The words are on QUB SC MS4.29 page 51/47/056/f23r, written beneath the unrelated live transcription notation of the tune of Caid é sin do’n té sin nach mbaineann sin dó.

Aim bagus umbo

A:B: here lies Lappin harper’s king

his finger Deserves a Golden string A:B

his Body lies here his soul flies high

Serenading David in the sky A B

here we spend our Days

Giveing Kate and Lappin a Praise AB

now we quit and bid a Dieu

to royal Kate and Lappin too A:B:

Royal

Bunting doesn’t tell us here what tune these words go with, but he does tell us a few years later, and we will discuss this below under the 1798 piano arrangement.

The c.1802 live transcription

Edward Bunting made a second, completely independent live transcription notation of our tune. It is in the notebook which he used on his tour of Mayo with Patrick Lynch in 1802. However, Burns’s March is not in the main body of that book with the Mayo song transcriptions; instead it is in a group of harp transcriptions written upside-down at the back of the book.

We don’t actually know when this group was done; I am guessing 1802 because that is when we know he was using the book, but it may have been earlier or later.

The live transcription notation of Burns’s March is spread over two openings. The main part of the tune is at the bottom of upside-down p.72 (olim p.63), on the lower left of the image of the opening. The other two tunes are Mailí Bhán on p.71, and I’ll follow you over the mountain on p.72.

Bunting’s title is “Pretty Peggy / Quin’s Burns March or 3rd tune / or Pretty peggy”. He has also written “set” in the left margin, as with the other tunes here. Someone else has added a pencil note at bottom right, perhaps in the early 20th century: “[Cont’d next page →”

All of the tunes upside down in the back of MS4.33.1 seem to be written one note higher than they could be played on a traditionally-tuned old Irish harp, and so my mp3 and PDF versions bump the whole thing down one note, to set the tune in G major.

You can see that Bunting has got muddled after the second bar, and he starts to write the third but scribbles it out and tries again straight after. Peering through the scribble, he seems to have trouble lining up the two staves.

This notation is extremely unusual for presenting what I am certain is a live transcription, on two staves, and it is even more unusual for presenting simultaneous bass and treble notes. We will discuss this a little later on.

On the next opening, written on upside-down page 70 (olim p.61) is a fragment titled “this belongs to Burns’s March”.

Here, the rhythm is less securely marked, and the barring seems all wrong. But nonetheless it seems clear enough. I think these are not simultaneous notes in treble and bass, but alternating.

There has similarly been a fair amount of commentary on these two pages; I wrote them up in my Progressive Lessons (2017), and Sylvia Crawford has written about them in her MA thesis (2018) and in her book An introduction to old Irish harp playing techniques (2021)

Bunting’s piano developments

Bunting made a number of piano arrangements which are derived from these live transcription notations. We will look at each in turn.

The unpublished 1798 piano arrangement

Edward Bunting made a piano arrangement which seems to be derived from the MS4.29 p.30 transcription notation and neat copy, which is in his unpublished Ancient & Modern collection of 1798. It is quite interesting as a neatened up and harmonised version of the transcription notation, and the way he handles the rhythm is very interesting. However, as I said in my Progressive Lessons book, I don’t know if this piano arrangement respects the harp playing of the original informant, or if this is Bunting applying his considerable piano arranging skills to make something coherent out of the messy and confused transcription notation.

Bunting’s title is “Iombo agus uambo – or Burns’s March – very ancient”. At the end of the tune he writes “From Dennis [H]empson of Magilligan – The following verse on a Celeb-/-rated harper about who lived about 2[5]0 years ago was translated by him”. Then there is the song text slightly changed from the MS4.29 p.51 dictation version, and then interleaved through the lines of the song he writes “This is also one of the Progressive Lessons taught young ha<r>pers & is the / fourth Tune Generally learnt”.

You can see that this is presented in the same key as the MS4.29 transcription notation, with three sharps in A major. There’s no tempo marking, but Bunting has given quite strong dynamics markings at least at the beginning. I would say he has added his own piano bass notes to the little repeated “chorus” each time, and also he has added bass notes to the third variation. He has also put more repetition of the little treble figures than what we see in the MS4.29 notations. Apart from that this seems quite a simple and austere tidying up of the MS4.29 notations.

The song lyrics written at the end are a close match from the text in MS4.29 (see above) but they are not identical especially in the way the chorus “Siombo agus uambo” is fitted in.

Remember, I think it most likely that when he did this piano arrangement (presumably in 1798), he hadn’t collected the other version (c.1802).

A manuscript piano arrangement

Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.12 is two boxes each filled with a selection of diverse loose leaves including letters, scraps of paper, and parts of at least one dismembered music book. On one of the 4-page sections extracted from a bound music book, there is a piano arrangement of Burns’s March. I do not know how we could date these odd pages. I am wondering if this page is pre-1809 because it seems an earlier revision of the tune than what we see in the published book; Colette Moloney says in her introduction & catalogue (ITMA 2000 p.225 & 714) that the paper is watermarked with the date 1805, so this arrangement must have been written after that. So let’s tentatively date this as perhaps 1805-1809. But I may be completely wrong there.

Bunting’s title is “Burns’s March or Hugad a gaddigh freed e moni” and he has written quite a lot of other things on this page. Under the first two bars he has written “open pedal” and “these two bars the / original harp bass”. Then at the bottom he writes “2 first bars / original harp / Bass”. Then there is a description: “this is one of the Irish tunes taught young <Irish> Harpers and I have given the Harp bass / in its original [state] with [???] little exce[p]tion as the characteristic wildness / and expression of this air would [have] been lost otherwise” (note that the third line of this is written above the other two but is joined by a long line to show the order of reading)

We can see that Bunting has moved away from the spare austere setting of 1798 and has added some more classical chordal accompaniments, but he keeps it in the same key and position on the staff as the previous arrangement and both live transcription notations (MS4.29 and MS4.33.1).

We also see that he makes a typo, omitting a bar at the end of the third system and having to add it at the end, marked with a big + sign. He also marks one bar “1st”, and provides an alternative arrangement for this bar at the end. My machine audio inserts the missing + bar in its correct position, and plays the alternative “1st” bar at the end after a pause.

The most notable thing about this piano arrangement is that it combines readings from the two different live transcription notations. It uses the first two variations from the MS4.29 notation, and then it provides the two variations from MS4.33.1. It does not use the third and fourth variation from the MS4.29 live transcription.

It also uses the very un-pianistic chords from the first two bars of the MS4.33.1 live transcription notation, and labels them here as “original harp bass”.

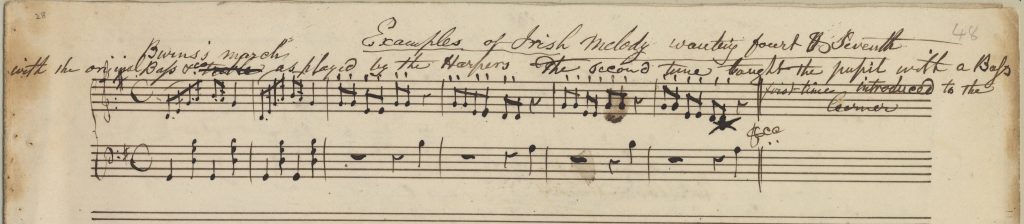

The “Examples of Irish Melody”

There is another notation of Burns’s March in another of the loose 4-page pieces from a dismantled book, now in QUB SC MS4.12. Colette Moloney can’t tell what the paper type or date is (Introduction & catalogue p.225). The page is headed “Examples of Irish Melody wanting the fourt & Seventh”. The page has neat copy notations of Burns’s March, Mailí Bhán, and Féileacán. All three tunes have been set in G major.

The notation of Burns’s March is titled “Burns’s march / with the original Bass &<ce> treble as played by the Harpers The second tune taught the pupil with a Bass / first time introduced to the / learner”.

I don’t really know what this is. It looks kind of pianistic. It may be derived from the live transcription notation in MS4.29 – the variation matches the 3rd variation there.

A number of the tunes on this 4 page fragment of a dissasembled book, make claims to be presenting the “original treble and bass” of the harpers, even when the arrangement looks quite pianistic. I haven’t yet studied this kind of claim in depth.

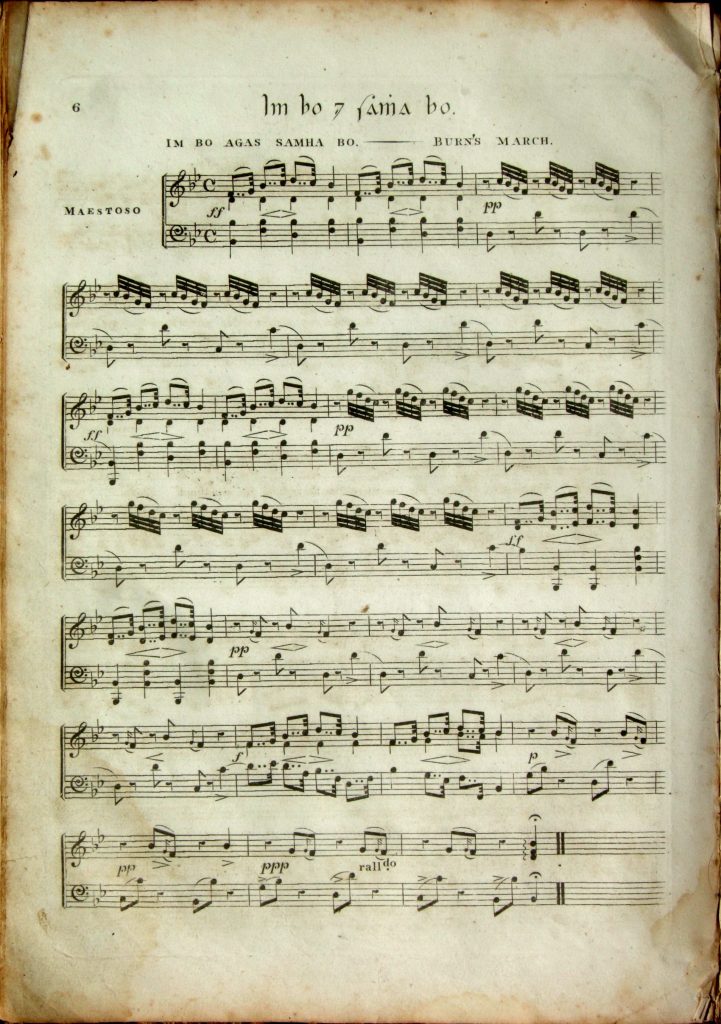

The 1809 published piano arrangement

Bunting published a piano arrangement in his 1809 printed book. Bunting’s title here is “Im bo ⁊ samha bo / Im bo agas samha bo – Burns’s March”

I think we can understand this as a more classical developed version of the MS4.12.2.10 piano arrangement; it has the same composite selection of variations (two from MS4.29 and two from MS33.1). Bunting has added dynamics, he has made the rhythm more angular, and he has changed the rhythmic alignment of some of the notes in the third variation. He has also dumped the “original harp bass” and made the bass more suitable for piano

The early 1840s edited version

After Bunting published his 1840 Ancient Music of Ireland, he started going back through his earlier published collections. His annotated copies of the 1809 and 1797 books are in the British Library (see Karen Loomis’s write-up). For most of the published tunes, he just added attribution information, but sometimes he also added other background information, and occasionally he edited the musical text.

For Burns’s March he did all three. At the top of the tune he wrote “From Hempson / one of the 1st tunes taught / to the young harpers (and) / one of the 1st in which grace notes appear / viz.” and then two tiny fragments of notation showing the four note descending run c-b-g-f and the two note grace-note figure g-f.

At the bottom of the page he wrote “This melody is very ancient being composed without the intervals of / 4th and 7th. Many different sets of the air are current in Ireland. / It is said to have been composed for the Burnss who were Lords of the / marshes or papes near Newry in the 13th century {see the peerage / and get an anecdote of them} many songs were adapted to this tune one / of which is ‘Did you see the black rogue'”

His music edits are modest, just the addition of extra harmony notes in the bass (and removal of a few bass notes from certain chords), to make them more pianistic.

I made a PDF typeset version and mp3 machine audio of the edited version that Bunting made in the early 1840s.

In summary, what can all these piano versions tell us? Perhaps not much from a traditional harp music point of view. They are very interesting in showing us Bunting’s development as a classical piano arranger, and how he wanted to present the Irish music. I think we could learn a lot by collating Bunting’s development as a piano arranger, with the description of changes over the generations from the late 18th to mid 19th century outlined by William Donaldson in his book The Highland pipe and Scottish society, 1750-1950 (Tuckwell Press 2000).

The other thing that they give us is the background and attribution information. We can look at this next.

Attributions to tradition-bearer informants

As far as I can see, we have three different independent live transcriptions in Edward Bunting’s notebooks that we should consider.

1. The live transcription “dots” notation on QUB SC MS4.29 p.30

2. The song words on QUB SC MS4.29 page 51

3. The live transcription notation on QUB SC MS4.33.1 p.72 & p.70 (upside-down)

A title for our tune also appears a couple of times in Bunting’s collecting pamphlets. He has written “[A]mbo agus” (the initial letter looks like A and I overwritten) in QUB SC MS4.29 p.170. This page also has unidentified fragments of transcription dots and I intend to study it fully at some point. It seems to be part of a pamphlet mainly full of live transcriptions from the playing of Denis O’Hampsey. Our title “Aimbo agus umbo” also appears on QUB SC MS4.29 p.103, at the head of a list of tunes. This page is in a section of the manuscript where the tunes are not clearly attributable, and I haven’t worked on the significance of these tune lists in the transcription pamphlets. So at this stage I don’t think these help us much.

Attribution of the song words

Lets consider the song words first. If we check my Old Irish Harp Transcription Project Tune List Spreadsheet, we can see that these words on page 51 are in the middle of a load of tunes all pretty securely attributed to Denis O’Hampsey, from p44 through to p.58. There is a tentative attribution to Hugh Higgins for two tunes on p.48-49, Kitty Tyrrell and the Friar and Nun, but even so the position of our song words in the manuscript, might make us suspect they were taken from dictation from Denis O’Hampsey.

This idea is strongly reinforced when we look at the earliest piano arrangement, in the 1798 piano manuscript. Here Bunting reproduces the words, with the heading “From Dennis [H]empson of Magilligan – The following verse on a Celeb-/-rated harper about who lived about 2[5]0 years ago was translated by him”. The implication here is that O’Hampsey made the English words as his own translation from a (now lost) Irish original.

Attribution of the MS4.29 p.30 live transcription dots

The line “From Dennis [H]empson of Magilligan…” has also usually been understood as an attribution tag not just for the words but also for the 1798 piano tune with its four variations, which clearly derives from the MS4.29 live transcription dots. This idea could also be reinforced by the “Harp Hempson” attribution tag written in the early 1840s into the annotated book.

I have doubts about this though. If we check in the Tune List Spreadsheet, we can see that page 30 is not near any other Denis O’Hampsey attributed tunes. Instead, it is near some tunes that are tagged Hugh Higgins. I also note that, just like the other tunes around it, it is notated one up rather than at pitch. All of the tunes collected from Denis O’Hampsey are notated at pitch.

How can we explain this? I think there are two possible explanations. One is that Bunting collected this tune from O’Hampsey in the 1790s but for some reason he noted it a note higher than pitch, and he wrote the transcription coincidentally into a different collecting pamphlet, near to other one-up tunes that he had got from Higgins and Byrne. The second possibility is that the “Hempson” tag in the 1798 piano book refers only to the song words; that the “Hempson” tag in the 1840s annotation is spurious (as many of those 1840s annotations seem to be); and that Bunting made the p.30 live transcription dots from a different harper, perhaps Hugh Higgins in 1792, in the same session as when he collected the tunes of Toby Peyton and Tá Mé Mo Chodladh from Higgins.

How can we decide which of these two possible explanations is most likely?

Attribution of the MS4.33.1 live transcription

The tunes written upside-down at the back of MS4.33.1 seem to form a group of live transcription notations all collected at the same time. You can check my MS4.33.1 index PDF to see the contents of this manuscript. Bunting used the main part of MS4.33.1 as his tune collecting book on his trip to Mayo in the summer of 1802 with Patrick Lynch, to make live transcriptions of song airs from singers and other tradition-bearers. The upside-down tunes at the back of the book seem to be different, and I don’t think they are from that Mayo trip. Some of them have bass notes marked or indicated, and I think they are all transcriptions from harp performances.

My Tune List Spreadsheet shows that three of these tunes have later attributions to Patrick Quin; Sylvia Crawford has argued in her MA thesis that all of the tunes in this upside-down section were transcribed live from Patrick Quin’s playing. The title of our tune, “Quin’s Burns March”, does not necessarily point to him as a live transcription source, but combined with the other attribution information it does seem likely.

Only one of the later attributions to Quin for a tune in this group gives a date, that is the Wild Geese which is said to have been collected from Quin in 1792 or 1800 or 1806. However, these are all late attributions written in the late 1830s or early 1840s, and so the dates may not be reliable. We know Bunting was using the front of the book in Mayo in 1802. But I don’t know when he may have opened the book at the back to transcribe tunes fom Quin’s playing. It may have been in the summer of 1802, on his way home from Mayo or it may have been some time later. I think it is less likely that it was before 1802, because the tunes do seem to be inserted into the back of the book.

I suppose it is possible that the entire book started out the other way up, that the Quin transcriptions were done first at the front, and then the mostly empty book was used for the 1802 Mayo trip starting from the back. However against this is that there is another live harp transcription on p.26 in the main part of MS4.33.1, inserted beneath one of the Mayo 1802 song airs, titled “Quins…”. It looks to me very much like Bunting has inserted a live transcription of this tune from Quin’s harp playing, into a space beneath his previous live transcription of the same tune from a Mayo singer. To me this strongly suggests that he was with Quin making transcriptions after the 1802 Mayo trip.

Other versions of the tune

There are quite a few variants of this tune, which we can recognise by their form or structure, or their title. I wrote a page about this on my old website back in 2014, but I think it’s worth revisiting this here and making some machine audios for you to be able to listen to the different versions.

The earliest version I have found was published in Scotland c.1776/8 by Daniel Dow, in his Collection of Ancient Scots Music p.26. Dow’s title is “Thug Bonny Peggie dhamhsa Pog – Bonny Peggie kiss’d me”. This clearly relates to the title “Pretty Peggy” which is in MS4.33.1.

There is a kind of typo in bar 10, where I think the two little semiquavers at the start of the bar ought to be gracenotes. But my machine audio plays them as written. There are what look like repeat marks at the end of each line, but they seem mal-formed and so my machine audio ignores them.

There are two versions published without titles in Patrick McDonald, Collection of Highland Vocal Airs (1784). No.68 is in the section headed “North Highland Airs”.

This one seems to be in G neutral mode, with no E at all and just a few passing B♭s which give it a minor sound. The F♯ in bar 5 is very much a classical minor addition. You can see the structure well with the two bar “refrain”, and the two different four bar sections which match the harp variations.

No.141 is under the heading “Argyleshire Airs”.

This one, in D major, also has the two bar “refrain” and two four-bar variation-like sections.

We have a version for Irish pipes printed in around 1804. This version seems somewhat different from the harp versions, but the title is enough to make us see the similarities. O’Farrell’s title is “Byrns March. a very old tune. Irish.”

Sylvia Crawford found another version of our tune under the title “Caismeachd Mac Cartha / Mac Carthy’s March”, printed in the Dublin Magazine, February 1843.

This is part of a series titled “The Native Music of Ireland” published by Henry Hudson in the early 1840s. The magazine changed its title over the years, and it was also called The Citizen and the Dublin Monthly Magazine. Hudson is known to have composed new tunes and passed them off as old traditional tunes.

I think it is possible that Hudson may have composed this, perhaps using Bunting’s 1809 published version as inspiration. Hudson would certainly have been familiar with Bunting’s work, and would have seen the similarities.

Petrie had a version of our tune in the mid 19th century, which was published as Stanford-Petrie no.1202. The title there is “Imbó agas umbó / A Dirge”.

Other song lyrics

In his early 1840s annotation into his own copy of the 1809 piano book, Edward Bunting wrote “…many songs were adapted to this tune one / of which is ‘Did you see the black rogue'”. I’m not sure what this refers to. There is a song “An Rógaire Dubh” which you can hear being sung in 1951 by Maggie McDonough; the tune she uses is not the same as ours and is also played as a fiddle tune. I suppose these words could fit the “refrain” of our tune.

Bunting also published a tune titled “Did you see the black rogue” as no.6 on p.4 of his 1840 Ancient Music of Ireland. But it doesn’t seem to be at all related to our tune.

In his article ‘Ceol na Filíochta’, in Studia Hibernica 32 (2002/2003), Breandán Ó Buachalla describes how 18th century Irish poets would often specify the name of the air to which their poem was to be sung to. He gives three examples which say that the air was titled “Iombó ⁊ umbó”, though of course this kind of title reference does not give us any information about the actual tune required. But it is certainly plausible that these poets were thinking of a variant of our tune, given that we have the “Iombó ⁊ umbó” title on Bunting’s MS4.29 transcription, and on Petrie’s “dirge” version. In the CD (track 12) accompanying the book Canfar an Dán by Úna Nic Éinrí, William English’s poem “Cré agus Cill go bhfaige gach bráthair” (p129) is sung by Padraig Ó Cearbhaill, but though the song specifies “Fonn: Iombó agus Umbó”, the tune actually used is not our tune but the spinning song “Is Iombó Erú” (Bunting 1797 no.50). It is a shame that they didn’t try using one of the variants of our tune for this song. I think they must have been following Donal O’Sullivan who (mistakenly) applied our title to the spinning song tune.

Hardiman (1831 v1 p146) published a song beginning “‘Si mo chreach! Bean cheannaighe na feile”, with the tag “Air ghuth Imbó a’s Umbó”. This had apparently previously been printed about 1792 by Charles Henry Wilson, in his Select Irish Poems under the title “Aoimbo agus umbo”. This book appears to be very rare and generally unknown and I have not seen a copy.

Conclusion

The tune of Burns’s March is obviously part of a huge network of songs and airs and instrumental pieces that were current in the 18th century, disappearing in the 19th and apparently totally gone by the 20th. Our two live transcription notations are fascinating glimpses into the performance practice of the old harpers. Quin’s (MS4.33.1) is especially important, with the tag connecting it to his teaching of the harp to his young student in the 1790s. The other one is much more problematical, with its corrupt rhythm and its ambiguous attributions.

Many thanks to Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections for the digitised pages from MS4 (the Bunting Collection), and for letting me use them here.

Many thanks to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for helping to provide the equipment used for these posts, and also for supporting the writing of these blog posts.

Here’s Sylvia Crawford demonstrating the c.1802 Quin version from QUB SC MS4.33.1

Simon, I have read with great interest of your study of Burns’ March, although, I am more familiar with it under the title of Byrne’s March. My grandmother was a Byrne from County Wicklow. She died in 1909, when my father was only three weeks old. When my father died in 1985, a close friend, Jim McConnell, a retired pipe major from the Royal Scots Guards, composed an lament marking his death. He wrote it as a highland pipe piece together with appropriate grace notes. I think he based it on Grainne Yeats’ version on the Irish harp (1980). Jim himself has now been dead for many years. I have the music notation for it if you are interested. Once again, thanks for your efforts with an ancient tune that has a soft spot in my heart, John Williams

Thanks John for sending the PDF of Jim McConnell’s composition (click to view)

A wonderfully comprehensive collection of Burns March variants—and bravo to Sylvia for finding “McCarthy’s March” —unknown to me, but obviously of the same ilk. In the late 1980’s I decided to compose a piece in the style of Burns March—and found it very challenging; I could not match its bold style, and thereby earned the woeful title “Ochone March” .

These variation patterns do appear in descriptive pieces and elsewhere, and they’ve served as a prototype for cláirseach battle scenes. As a pedagogical tune, the “Burns March” theme is but the 2nd line of Fair Molly, indeed some variations utilize fingering patterns of Fair Molly. Additionally the piece can serve as a sort of template upon which treble hand figures can be performed in both “stopped” and “open” style (Bunting’s “staccato & legato”). But of course, this is my interpretation. However, there is one thing I find myself disagreeing with and that is your dismissal of the earliest version…which is obviously the best, and clearly notated as day and night. Perhaps this difference may be attributed to my not being absolutely literal in interpretation—and that I allow myself the freedom to “reverse engineer” Bunting’s published piano version.

Yes didn’t Charles Guard also record his own composition based on Burns’s March as well? I think your comment about it being a kind of open-ended “template” is more useful! I can imagine a harp student spending years studying variations of Burns’s March with their master…

Marvelous to see all this Simon. Very interesting to see all the various possibilities of the history and nature of the piece.

This was such an interesting read – thank you Simon. Goodness – are the threads that weave through time and music so interesting and challenging to link together sometimes. If only we could go back and be a fly on the wall to see how they taught, performed, composed and generally lived!

Hi Simon,

love your comprehensive comparative research practice methodology. This article is an exemplar.

William Donaldson’s Pipe|Drums Pibroch Set Tunes comparative analysis is analogous.

I have for a number of years been exploring the setting of oral tradition accapela vocal tune variants to instrumental wire harp tunes as countermelodies anchored on gracenote ornamentation and vocables.

I contend this align’s with Boethius’ theory that the role of ornament is to mediate transitions in state from a movement towards tension to a movement towards resolution. I’m an architectural ornament theorist by trade.

Revived Ap Huw Cerdd Dant follows this model. I came to it by ear, mapping tunes with the same titles but variant melodies as a starting point and finding alignments via the ornament. Vocals often started part way through an introductory musical phrase, locking in with syllabic phrasing and both ending together.

Welsh Penillion song is a surviving cultural practice but most underlying harp tunes are originally vocal airs, effectively a vocal over a vocal melody, without the structural grounding of earlier bardic musical and poetic practices.

The song lyrics collected here by Bunting together with the wire harp tune from O’Hemsey are a rare early correlation to consider.

The title variants “Iombo Agus Uambo”, “Iombó ⁊ umbó”, “A[im]bo agus um[b]o”, “Aim bagus umbo”, the chorus “Siombo agus uambo” etc potentially translate as something like “around a cow, and from a cow”. The Bunting provided translation “Steal a Cow and Eat a Cow” and even “Take care of the rogue coming / thro’ the marsh” suggest the tune may be akin to a Clan Gathering Pibroch genre, where gathering refers to seasonal cattle raiding, and the title potentially refers to seasonal feasting after a cattle raid.

You have argued this tune is Irish Ceol Mor which I agree with. In its compressed form it meets all the stylised theme and variation criteria of Pibroch and particular Cerdd Dant genres.

Having an analogous title to a Pibroch Gathering or Cattle Raiding tune, a staple of the bardic epic, strengthens that connection and perhaps helps date it to a period when Irish Clan Cattle Raiding was still practiced and celebrated, or it refers back to that time, or it indicates the tune derives from or shares a Scottish Gaelic cultural context.

The title variants of “Iombo Agus Uambo” all have a syllabic consonant and vowel rhythm reminicient of Pibroch Songs, Scottish song vocables and in their most developed form Canntaireachd.