In the early 1900s, the Belfast carpenter William Savage and his younger brother Robert made a very decorative copy of the medieval Brian Boru (Trinity College) harp. When the harp was finished, brass wire strings were fitted by George Jackson.

George Jackson had learned harp from Patrick Murney, in a lineage going back to the 18th century Irish harpers. I recently started to wonder if some of Jackson’s strings might still be on the harp.

Provenance of the harp

I should briefly run through what I know of the provevance of this harp, which will explain the reason why I wanted to go and look at its strings.

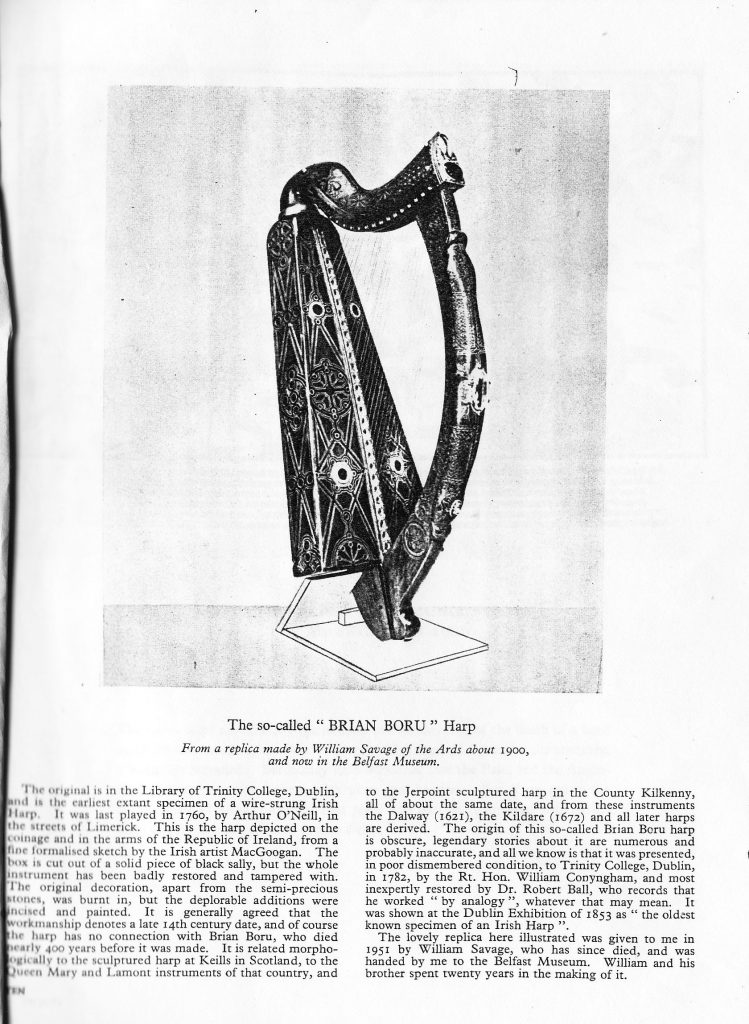

In his 1954 book The Story of the Irish Harp, Richard Hayward published a photograph with a caption and a very brief paragraph:

…a replica made by William Savage of the Ards about 1900, and now in the Belfast Museum.

Richard Hayward, The Story of the Irish Harp, 1954, p.10

…The lovely replica here illustrated was given to me in 1951 by William Savage, who has since died, and was handed by me to the Belfast Museum. William and his brother spent twenty years in the making of it

William Savage also wrote about the stringing of his harp, in a document which I found in the Archive of the Arts & Industry Division of the National Museum of Ireland. I transcribed and discussed this document last year, but it is the introduction paragraph that is relevant here

Irish Harpers particularly from Belfast

NMI archive, file AI.80.019

by George Jackson (Clock maker to trade) Belfast

this information taken down by me William Savage

from George Jackson when he was stringing my Harp

a copy of the O’Brian Harp now in Trinity College

Dublin. George was a fair player of the Harp.

Anything he learned was from Pat Murney.

Let’s briefly look at these three people named there.

William Savage

William Edward John Savage was born on 20th September 1867 in Holywood, Co. Down, a few miles outside of Belfast. His father was Robert Savage, a carpenter, and his mother was Sarah Quin.

William followed his father by also becoming a carpenter, later a joiner. In the 1901 census he was aged 33, and living at 6 Annadale Street, Belfast, with his mother Sarah, his three sisters Sarah Ann, Mary M, and Hannah, and his youngest brother Hugh Louis, a solicitor’s clerk. The houses on Annadale Street were destroyed in the war in 1941, and the cut through from the Antrim Road continuing on to Sheridan Street is now where Annadale Street used to be.

By 1907 they had moved to 9 Vicinage Park, but by 1908 they seem to have moved again, to 8 Lincoln Avenue. (Vicinage Park and Lincoln Avenue are back-to-back, behind St Malachy’s College. The houses between Vincinage Park and Lincoln Avenue were destroyed by bombs in 1941). The 1911 census tells us that William was 42 years old, and lived at 8 Lincoln Avenue with his mother Sarah, his sisters Sarah Ann, Mary and Hannah, and his younger brother Robert. Both William and Robert are listed as joiners. William is listed as a joiner at 8 Lincoln Ave in the street directories for 1908 through 1910, 1918, & 1932.

Savage joined the Belfast Naturalist’s Field Club in 1913, and he exhibited his copy of the Brian Boru harp at meetings of the club, e.g. in 1932 and 1934. He also appears in the Belfast Gazette, 10th January 1936, where he and his youngest brother Hugh Louis are the executors of the will of “Henry McMullan, late of Brockabuoy, county of Londonderry, Farmer, deceased”.

William Savage also owned an antique Irish harp. Robert Bruce Armstrong made a note on a folded slip of paper:

Mr William Savage

RIA Library SR 23 G 35; see Sanger & Billinge handlist

of 9 Vicinage Park

Belfast writes to say

that he has in his possession

a fine specimen of an

old Irish harp which

belonged to Valentine

Rainie or Ranney.

Unfortunately Savage’s original letter is not included in Armstrong’s papers at the RIA, and Armstrong’s note is not dated, though it presumably dates from after the publication of Armstrong’s book in 1904. I wonder if Savage sent more information, or even a photo? There is a poor photocopy of a photograph of this harp, in NMI archive file AI 80 019. On the back it says “This photo was taken in 6 Annadale St. by James A Napier, now Rev. James Napier, P.P. He was at that time in St Malachy’s College…” It clearly shows Rainey’s harp in a cluttered small Edwardian room. The photocopy is very poor but there is a 5-string banjo prominently displayed beside Rainey’s harp. This file in the NMI archive contains other photocopies of information from Savage including his information on “Irish Harpers Particularly from Belfast”, as well as correspondence relating to the NMI purchase of the harp in 1980. The harp is now in storage at the NMI, accession number NMI DF:1980.6. It is a large “hybrid” Irish harp, similar to the Egan wire-strung harps made in the 1830s. In Napier’s photo taken in Savage’s house, the harp has a full set of strings on it; now it only has a few stubs on it which I think are gut.

In the 1901 census, William is listed as the only member of the family to have the Irish language. I presume he was learning with Conradh na Gaeilge which opened a Belfast branch in 1895. He was interested enough in old harps, not only to own Rainie’s mid-19th century harp, but also to make his own copy of the medieval Brian Boru harp. And then, when it was time to fit strings to the completed harp he had made, he went to George Jackson.

George Jackson

Until I found William Savage’s notes in the NMI archive, I had not heard of George Jackson.

I have been digging for him in the records as well. As far as I can see, he was born in born in the summer of 1833, in British, which is on the north edge of Aldergrove Airport on the east side of Lough Neagh. He may have had some early connection to the town of Ballymena.

I looked in Geraldine Fennel’s List of Irish Watch and Clock Makers (1963) but there is no listing for George Jackson.

I checked in the Belfast street directories, online at LennonWylie. George Jackson is listed as a clock maker in Foreman Street in the 1868 street directory. The entire street layout of the area has gone completely; apparently after the war everything was levelled and new street layouts were made. As far as I can see, Foreman Street ran along behind where the Living Hope church now stands. There is also a Geo. Jackson watch maker at 11 Little Grosvenor Street in 1877. Little Grosvenor St. has also vanished completely; it ran through what is now the Arundel Courts area.

George Jackson, “Formerly Clock Maker”, is listed age 67 in the 1901 census, as an inmate of Clifton House old people’s home. Clifton House archives record him as being admitted on 20 Oct 1900, age 67, and they say he died on 21 Jul 1909. His death record says he is “from Ballymena” and says he died at the Cottage Hospital, Ballymena, but it gives his age as 65 which seems wrong.

Our other key piece of information about Jackson comes from Savage’s notes:

George was a fair player of the Harp. Anything he learned was from Pat Murney.

NMI archive, file AI.80.019

Patrick Murney

Patrick Murney was one of the youngest cohort of blind charitable students at the second Belfast Harp Society. Murney seems to have been born in the mid 1820s. In George Jackson’s information which he dictated to William Savage, we get some interesting anecdotes about Murney. We also have a couple of nice portraits of him; there is a very lovely sketch by Lady Dufferin dated 10th October 1839 (plate 11 of the 2013 Ardrigh edition of Annals of the Irish Harpers). There is also a watercolour drawing also dated 1839, which you can view online at NMNI.

Murney went to the Irish Harp Society where he was taught the harp by Valentine Rainey or Rennie (c.1795/97 – 1837). Rennie had learned to play the harp as a blind charity student at the first Irish Harp Society School, under the tuition of Arthur O’Neill (1734 – 1816). O’Neill was one of the last generation of country harpers who had learned in the old tradition before the urban revival efforts of the early 19th century. Arthur O Neill had learned to play the harp from Owen Keenan in the first half of the 18th century.

Rainie died in 1837, though the school carried on for a couple more years; after that the young boy Murney would have been on his own as a harper. Dr. James MacDonnell may have acted as a mentor or patron to Murney; in 1839, MacDonnell referred to him as “my little harper” (Annals p.277). MacDonnell died in 1845. Murney was well established with his own premises. John Bell described Patrick Murney in 1849: “He plays in Little Donegal St, Belfast, in his own house. He is a little fellow of about 25 years old” (H.G. Farmer, ‘Some notes on the Irish Harp’, Music and Letters 24, 1943 p 106). We can find Murney in the 1852 Belfast street directory at 38 Little Donegall Street. I think this row of houses is long gone and would have stood where the Library Street car park is now.

Murney was again mentioned briefly by James O’Laverty who describes “when he was stringing harps for me on the second of July 1882” (James O’Laverty, ‘The Irish Harp’, in Denvir’s Monthly, 1903). I don’t know what harps these might have been.

George Jackson tells us in his notes that Murney “had been some time in the Nazareth Home Ballynafeigh – but I think he came out. and after some time died in the Poor House”. Murney’s death record says he died in the Nazareth House on 5th March 1890. It says he was 52 years old when he died, but this is surely a scribal error, or he would have been a toddler in 1839. He might have been MacDonnell’s “little harper” but not that little!

Viewing William Savage’s harp

I wrote to National Museums Northern Ireland, enquiring if they had a decorated copy of the Brian Boru harp. I got a reply, including a catalogue entry:

BELUM.V2038

WOOD Harp

“Brian Boru” Harp

19th century

wood (oak) & crystals & white metal mounts

height : 95cms;length : 32.5cm;width : 47 cm

design: copy of early Irish harp, celtic interweave carving and applied crystals in white metal mounts

I thought this seemed very likely to be Savage’s harp, and so I made an appointment to view the harp in the Museum storage where it is kept.

After coming back from Belfast, I saw in Sanger & Billinge’s handlist that William Savage had written a letter to to R.B. Armstrong, dated June 1908, and enclosing a photograph of the harp. I went to Dublin to visit the Royal Irish Academy and see the letter, and I made this full transcription for you:

Belfast 8 Lincoln Avenue

RIA Library SR 23 G 35

June 1908

Dear Sir

I don’t know whether or not

you remember me writing you in Dec ’06

relative to the O’Brien Harp now in Trinity

College. My Brother Robert and Myself

have succeeded in making a Fac Simile

and furthermore we have restored lost

portions, that is to say, we have made a

copy of what we thought it originally

was, to the best of our ability, previous

to any of the jewels having been stolen from

it. I need not explain to you about the

timber or what is already on the original,

I will only explain what we have restored

1. The original has only 29 Escutcheons

we put on the 30.

2. The original, lost the 4 silver Escutcheons

from Sound holes, we have re-placed

them on our copy

3. The Original Silver Cap has lost one Chrystal

or Stone. We have re-placed it with an

Emerald shade of Glass, immediately

below the Rock-Chrystal

4. The original Serpent has lost all its Chrystals

or Stones, we have restored all, to the best of

our ability with what book knowledge we

has of Irish Antiquities. In the centre panel

of Serpent we have an Oval Rock Chrystal

and 6 amethysts set in Silver, this silver

setting forms a continuation of the rope

pattern which divides panels on back of Serpent

and 4 of the 6 little amethysts form buds for

leaves which are close to silver setting. the

other 2 intersecting the rope border on wood

and silver setting which which fill exactly the space

where originally had been a Chrystal

The lower panel of Serpent has also lost the setting

which was oval.- we have restored this in a

large Amethyst set in Silver, which also fills

the space originally occupied by a similar Stone

(I may here remark that the Amethysts were got

on Achill Island, so that far as possible everything

used is Irish). The curved head has been

restored with all silver bosses. complete

The 30 brass pins or keys are brass

The strings also brass, have a beautiful tone,

in fact, surprising, and far beyond anything

I had anticipated. The tuning has risen the

sound box so that now it has the same rise

as the original. I would not go to the

trouble of explaining in so detailed a

manner only that I know I am talking

to a Gentleman, who has taken great pains

in examining the Original Harp in Trinity,

previous to publishing a work which I have

seen in our Belfast Library fully describing it

We have not as yet got an impression of the

Badge supposed to have been on the Harp,

but with this exception, we have done our best

to reproduce it , and when acknowledging

your very kind letter of Explanation, I remarked

that as soon as we would have our Fac Simile

completed we would send you a photo of it.

We have just now received the Proof, which we

hope you will accept, although we have seen

your very fine diagrams in in our Library work,

but as our copy has all parts restored, we dont

think it out of place sending you this Photo,

of the first Fac-Simile of the O’Brien Harp

ever accomplished.

Very Sincerely Yours

William Savage

R. Bruce Armstrong Esq

6 Randolph Cliff

Edinburgh

The photo is very high quality; it is signed “R. Welch” and shows the harp complete and strung, sitting on a brocaded cushion with a fancy net curtain draped down behind it. You can see a fragment of panelled window frame and Venetian blind behind. I think the photo and the letter gives us a lot of very interesting detail about the making of the harp. However, I had not seen them when I went to Belfast to the Museum store to view the harp. I only paid cursory attention to the construction and decoration; the harp is in very clean condition and does not look like it was played very much if at all, though there is at least one crack in the neck. The decoration is very crisp and sharply cut with the lines formed of deep square-section channels.

The overall form of Savage’s harp seems to have been closely modelled on the plaster-casts. He uses the “spurious” left side decorative motifs, the same as the plaster casts. He has also copied the distinctive curved foot of the plaster-casts. On the other hand, Savage’s decorative carving on the neck and pillar are much more developed than the plaster-casts; he must have been to Trinity College to sketch the designs of the original.

The harp seems to be made of a light-weight soft pale wood, and the back panel looks like oak, made from two pieces joined along the centre, and attached to the soundbox using wood screws. On the inside, the back panel has been blackened, perhaps to make the silver-coloured metal rings round the soundholes show better. The soundbox is carved from a single piece of wood; there are two internal braces carved integral to the soundbox, running the full length each side of the string holes, so that the toggles sit in a deep U-shaped channel. This is very non-standard for old Irish harps but was perhaps inspired by similar long braces sometimes glued inside composite pedal-harp style soundboxes. I think that Rainie’s harp (NMI DF:1980.6), which belonged to Savage, has similar shaped long internal braces, flaring at the bass, glued inside the soundboard.

I was also interested to look at the string shoes and the tuning pins. Compared to the beautiful gem-settings, the string shoes are fairly simple, flat hammered brass horseshoes with punched ends, each fixed with three nails whose heads have been filed flush. The shoes of the three missing strings didn’t show any wear from the string pressing against the brass, again suggesting the harp was not used much.

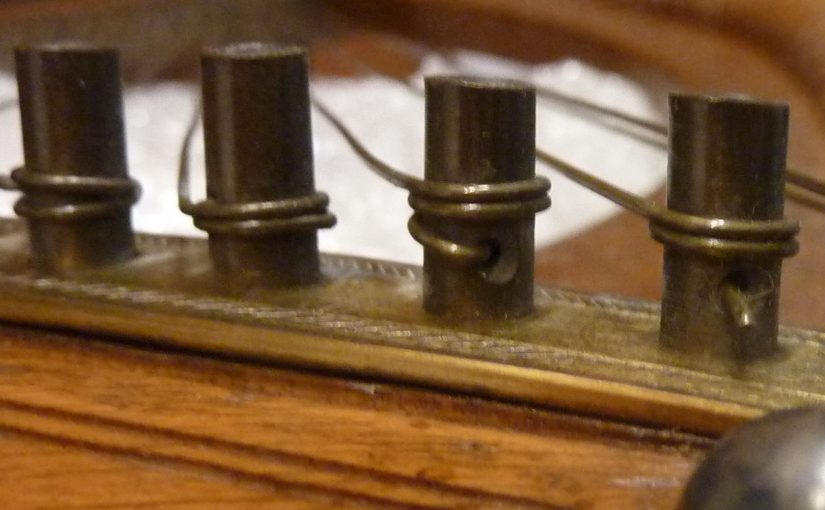

The brass cheek-bands were well-made, fixed with brass countersunk slot-head wood screws, and decorated with engraved step-patterns. But the tuning pins were pretty crude. I wondered if they were some off-the-shelf industrial component. They are brass taper pins, perhaps similar to modern no.5 size. Their small ends (on the left side of the harp, where the strings are attached) are countersunk with a small hole drilled longitudinally into the end. Their drive ends (on the right side of the harp) are slightly crudely filed down from the tapered shaft to make an under-size tapering square drive.

The harp has an inked number written on the back, “46-1951”. The NMNI curator, Tríona White Hamilton, told me that this was a cataloguing number, indicating that the object had been catalogued in 1951. This fits with Hayward’s account that he got the harp from Savage in 1951 and passed it on to the Museum.

I think this harp that William and Robert Savage made, has three different and independent levels of significance. One is the whole arts-and-crafts Gaelic revival of the late 19th and early 20th century; it is a powerful artistic statement of the Celtic revival. The second significance is as a part of the whole development of the idea of the Brian Boru harp as some kind of archetypal or ideal model for the Irish harp. And the third is the reason I went to Belfast to the museum store – the possibility that the stringing was done by a tradition-bearer.

The strings

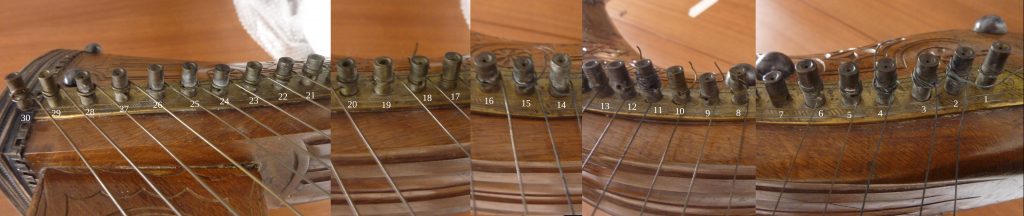

I photographed the pin windings of all the strings, and I used an endoscope to photograph the toggles on the inside of the soundbox (the harp does not have back access holes). I also measured the gauges and lengths of the strings on the harp.

Materials

I did not test the strings with a magnet, but from visual inspection they are clearly all of copper-alloy wire, except for numbers 2, 3, 4, 11, and 15 which look like iron or steel – these five wires have a grey powdery surface on the windings and in some places a slightly flakey crust.

Method of winding the tops onto the tuning pins

I think there are about three different methods of winding the tops, which we could imagine were done by three different people. There is a very neat winding (type A), there is a similar but much less competent and less functional winding (type B), and an atrocious messy winding (type C). I find it significant that the atrocious type C is used for all of the iron wires.

On pin no.3, the messy iron winding is wound over the top of a fragment of a neat brass string.

The neatest type A inserts the string into the little hole drilled through the pin, and then winds about 2 turns of the pin close and neat, outwards towards the tip of the pin, so that the string falls towards the treble end of the harp. The less neat type B has a long tail end. The messiest type C has less or no windings, as if the wire was pulled tight through the pin hole, and then the long tail end wrapped untidily around the pin.

Method of tying the bottoms inside the soundbox

My photos of the inside are much poorer, because I was only able to use the endoscope. The big carved in braces also made it even harder to image the inside.

Again I would describe three different methods of tying the strings inside. The neatest type (A) inserts the string through the hole drilled into a thick brass slug with rounded ends, and then is secured with a simple overhand knot or similar on the inside of the toggle hole. There is no winding around the toggle. The less neat type (B) is on the same kind of toggle. It tends to go through the drilled hole, and then half wrap around the toggle with a kind of overhand knot hidden between the toggle and the wood of the soundbox. The third type (C) used for the iron wires, doesn’t pierce the toggle but wraps two or three times round the toggle and is then wound around the standing end of the string. Sometimes it is very hard to tell if the wire goes round the toggle or not because of the way the photographs don’t show all the sides very well. That’s my fault!

Reviewing my endoscope photos, not all of the windings are visible and some are poor, so I can be less confident about what method of toggle knot is used on each. You can see that I can’t identify numbers 9 and 10 on my endoscope photos.

Collation of the different wires, tops and bottoms

We can make a little table to collate the tops, bottoms and wires, to see if there is a pattern.

| No. (type) | metal | pin winding | toggle winding |

| 1. (A?) | copper alloy Broken at bottom | 2 turns outward, neat | missing (may be loose inside harp? |

| 2. (C) | Iron? Grey-blue corrosion surface | tail wound round and round untidily | threaded shiny brass, diagonal. 3 turns round toggle, knot not visible |

| 3. (C) | Iron? Grey-blue corrosion surface Plus fragment of brass | Fragment of brass. Iron string with tail wound round and round untidily | threaded shiny brass, longitudinal. 3 turns round toggle, twist round standing end |

| 4. (C) | Iron? Grey-blue corrosion surface and crust | tail wound round and round untidily | slug, diagonal. 2 turns round toggle, twist round standing end |

| 5. (B) | copper alloy | 4 ½ turns, crossed over | pierced slug across. through hole, tail end? |

| 6. (B) | copper alloy | 3 turns, crossed over | pierced slug across. two halfs turns through hole? twisted round standing end? |

| 7. | completely missing | ||

| 8. (B?) | copper alloy | half a turn, long tail wrapped round | Pierced slug across? overhand knot? |

| 9. (B?) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, long tail | not visible in my photos |

| 10. (B?) | copper alloy | half a turn, long tail sticking up | not visible in my photos |

| 11. (C) | Iron? Grey colour | tail wound round and round untidily | threaded shiny brass, longitudinal. winds round toggle |

| 12. (B) | copper alloy | no turns, long tail? | Pierced slug across. String through hole, long tail end? messy and loose |

| 13. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Slightly diagonal? String through hole, overhand knot? |

| 14. (B) | copper alloy (slack) | no turns | pierced slug, diagonal? half wrap though hole |

| 15. (C) | Iron? Grey-blue corrosion surface and crust | no turns, long tail wound round and sticking out | threaded shiny brass, longitudinal. 4 winds round toggle? |

| 16. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Pierced slug across with patch of corrosion. String through hole, overhand knot |

| 17. (A) | copper alloy | half a turn, neat | Pierced slug across. String through hole, overhand knot, long tail |

| 18. (B) | copper alloy | half a turn, long tail sticking up | Pierced slug across, half wrap through hole, ends against the wood |

| 19. (B?) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Dark pierced slug across. half wrap through hole, loop behind toggle |

| 20. (A) | copper alloy missing; coil on pin only | 2 turns outward, neat | missing |

| 21. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Pierced slug across? String through hole, overhand knot? |

| 22. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Pierced slug across? String through hole, overhand knot |

| 23. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Pierced slug across? String through hole, overhand knot |

| 24. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Pierced slug across? string through hole, overhand knot |

| 25. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Pierced slug across? Slightly angled? String through hole, overhand knot |

| 26. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | Pierced slug across? String through hole, overhand knot |

| 27. (A?) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | angled? string knot not visible on my photos |

| 28. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | ? brass slug with hole. String through hole? overhand knot? |

| 29. (A) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, neat | brass slug with hole. String through hole, overhand knot |

| 30. (A?) | copper alloy | 2 turns outward, long tail | brass slug with hole. String through hole, overhand knot |

The column headed “type” is my impressionistic assessment as to whether the string is super neat and consistent, or a bit messy, or atrocious as described above. I think you can see that there is a pretty good correlation between the tops and bottoms, reinforcing my impression that these are three genuine different “hands” working on the harp.

Here’s some direct comparisons of the different types.

I think it is clear that most of the strings were fitted with the back of the harp removed. Because of the way the back panel is not really properly recessed like on the old harps, but is fitted with wood-screws, it could easily be removed even with the harp up to tension. I think you could only get the toggles neatly lined up cross-ways like that with the back off. The type C iron strings were either fished through the soundholes with the back on, or the person fitting them really didn’t care about making them line up with the others.

Understanding these different ways of fitting the strings

I have described and illustrated the different string attachments. My documenting of the strings is not perfect by any means, but I am fairly happy with my summary above.

It looks to me like the type A strings were put on the harp by someone who knew what they were doing. There is a deliberate way of working, fairly consistent and fairly neat.

Were type B strings replacements done by someone else, perhaps someone who didn’t have a lot of experience, but had been shown the general method by the person who did the type A ones?

Were the type C strings replacements done in a hurry much later by someone who didn’t really know what they were doing?

Did George Jackson do the type A ones? Did William Savage do the type B ones? And did Richard Hayward or William Savage do the type C ones in 1951?

The gauges

I measured the gauges of all the strings except no.16 which is completely missing, and no.20 which has only the coil on the pin. I also didn’t measure the fragment of brass wire underneath the iron wire winding of no.3.

I measured the lengths with a long lightweight plastic ruler. Because I didn’t want to put any weight or pressure on the harp or the strings, I guess the lengths are only to within half a centimeter either way. I measured the gauges with a resin dial caliper. The caliper is gradated every 0.1mm but again I was taking extreme care not to damage the fragile strings and so I think my measurements are only accurate to 0.1mm either way.

| no. | Length (cm) ± 0.5cm | diameter (mm) ± 0.1mm | material |

| 1 | 8 | 0.35 | copper alloy |

| 2 | 9 | 0.4 | Iron? |

| 3 | 10.5 | 0.4 | Iron? (Plus fragment of brass) |

| 4 | 11.5 | 0.45 | Iron? |

| 5 | 13 | 0.4 | copper alloy |

| 6 | 14.5 | 0.4 | copper alloy |

| 7 | 16 | ||

| 8 | 17.5 | 0.5 | copper alloy |

| 9 | 19.2 | 0.5 | copper alloy |

| 10 | 21 | 0.5 | copper alloy |

| 11 | 23 | 0.5 | iron? |

| 12 | 25 | 0.5 | copper alloy |

| 13 | 26.7 | 0.55 | copper alloy |

| 14 | 29 | 0.55 | copper alloy |

| 15 | 31 | 0.55 | Iron? |

| 16 | 33.5 | 0.65 | copper alloy |

| 17 | 35.5 | 0.55 | copper alloy |

| 18 | 38.5 | 0.55 | copper alloy |

| 19 | 40.2 | 0.575 | copper alloy |

| 20 | 43.3 | copper alloy | |

| 21 | 45.9 | 0.775 | copper alloy |

| 22 | 48.5 | 0.775 | copper alloy |

| 23 | 51 | 0.825 | copper alloy |

| 24 | 53.8 | 0.85 | copper alloy |

| 25 | 56.5 | 0.9 | copper alloy |

| 26 | 59.2 | 0.9 | copper alloy |

| 27 | 62 | 0.9 | copper alloy |

| 28 | 64.9 | 0.9 | copper alloy |

| 29 | 67.5 | 0.9 | copper alloy |

| 30 | 70.5 | 0.9 | copper alloy |

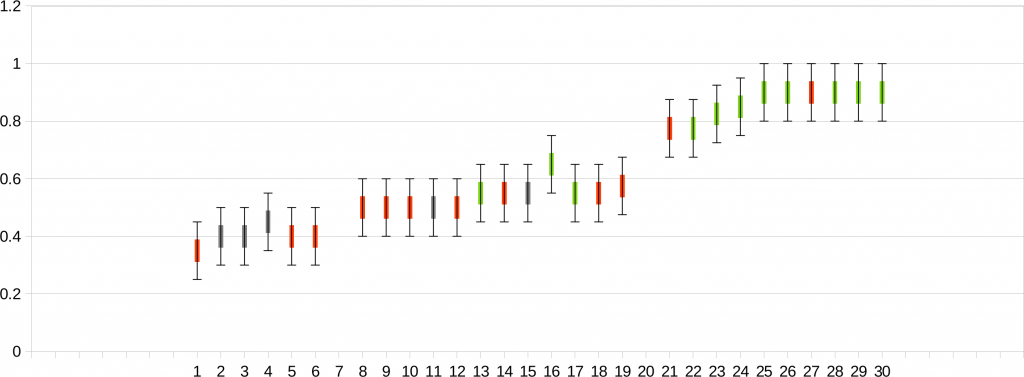

We can visualise the data on the string gauges by plotting it on a chart to see how the gauges group. I have added 0.1mm error bars so you can see the spread of probable actual measurements.

This is kind of interesting; it gives us reasonable gauges for this kind of harp, just what we would expect. It is similar to the gauges I would put on a medieval Irish harp nowadays.

I also note that the type B and the type C (iron) strings are very much in line with the measurements of the type A strings. Whoever was replacing strings either measured to get a match, or had some kind of string chart or instructions.

Pat Murney’s rules for stringing an Irish harp

William Savage in his notes, tells us about George Jackson, that “Anything he learned was from Pat Murney”. We have the “rules for stringing” which Patrick Murney dictated in July 1882

RULES FOR STRINGING THE IRISH HARP OF THIRTY-SIX STRINGS

James O’Laverty, ‘The Irish Harp‘, in Denvir’s Monthly, 1903

Use hard drawn wire

No. 18 in the 8 strings nearest the pillar.

No. 20 in the 7 following.

No. 22 in the 7 following.

No. 24 in the 7 following.

No. 25 in the 7 following which are the shortest

Now obviously there are problems here. We have neither the string lengths, nor the notes, to which Murney’s harp was tuned. And we also don’t know what gauge system he was using, to translate his gauge numbers into millimeter diameters.

However we do know what Murney’s harp was like; it was a large floor standing “hybrid” harp which looks like it might be one of the big Egan wire-strung harp in the portraits of him. Murney’s harp seems to be lost; Jackson says (in Savage’s notes) “I am not sure about his Harp but I heard that he had left it in Ballynafeigh where he had first went”.

I included Murney’s “rules” in my study of the stringing and tuning of the big Egan wire-strung Irish harps. I believe that Murney’s harp was likely tuned with the lowest note as bass G, two-and-a-half octaves below middle c’ and one octave below the bottom line of the bass clef. I also believe it is likely that Murney’s harp was tuned to a straight scale with no doubled unison notes and no gaps.

We also don’t know what notes Savage’s harp was meant to have. I did my usual analysis of the scaling of William Savage’s harp, and it seems to me likely that (if as I imagine) it was tuned to a straight diatonic scale, the lowest note would most likely have been E in the bass, not quite two octaves below middle c’, and one ledger line below the bottom of the bass clef. Any higher and the treble strings would be in danger of snapping.

(Incidentally, the treble iron strings 2-3-4 are not the highest stressed; I think 6-7-8-9 are the limiting strings. But the thinnest high strings are the quickest to break if the harp is neglected or bumped in transit)

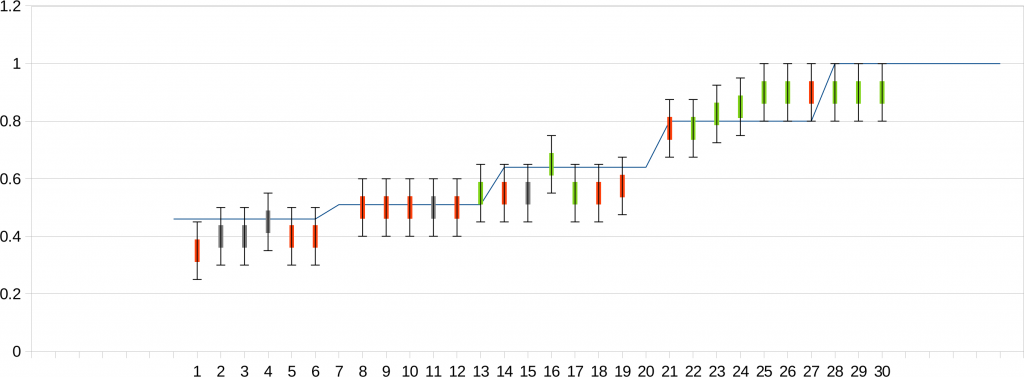

Making a somewhat arbitrary choice of using AWG to convert the gauge numbers to mm diameters, and assuming Murney’s chart has GG as the lowest note and Savage’s harp has E as the lowest note, we can overlay the two charts to see how they compare:

I hope you can see from this chart that the wires now on William Savage’s harp are consistent with the “rule” from Patrick Murney, who George Jackson said he learned from. The only outlier is string no.1 which seems too thin. This could be measurement error on my part, I don’t really know. Maybe my ± 0.1mm is optomistic.

The other possible aberration is the bass octave; though my measurements appear consistent with Murney’s rule, it is also possible that Jackson adjusted the rule here because that bass octave would have been a lot shorter than the same octave on the big hybrid harps. Again we can’t tell without much better measurements.

You can also see that this chart doesn’t “prove” that Savage’s harp used Murney’s “rules”; the wide error margins would also be consistent with other systems, for example all of the strings from 8 through to 20 on Savage’s harp could actually be the same gauge. Without much finer measurements there is no way to tell. Using a different gauge system such as SWG would also give different mm gauges for Murney’s system.

For some context, we could look at my string analysis of the Rev. Best harp. Compared to that, the stringing of William Savage’s harp is totally straightforward and very believable.

Questions

Why are the strings wound outwards from the neck? I think there may be two reasons; one is that the holes through some of the pins seem very close to the neck. And second, Murney’s harp (and Rainey’s before him) had bridge-pins and so it didn’t matter which way the string was wound on the tuning pin.

Why are the toggles pierced and made of brass? Is this a component that a clockmaker would have in his workshop? It seems that the normal 18th century practice that Arthur O’Neill would likely have used, was to have a wooden toggle, and to wind the string around it.

I have often wondered how much classical pedal harp influence there was on the Belfast Harp Society teaching. Obviously they had the teacher to student lineage going back to Arthur O’Neill; they still used harps with brass wire strings, they still played left treble and right bass. But I wonder if the urban charitable school, supported by well-to-do gentlemen, might have also brought in classical music teachers to improve the boys’ knowledge of harmony and classical music principles. I don’t think they tuned their big Egan harps with na comhluighe unison strings or gapped basses. We see the hand positions of Patrick Byrne and Pat Murney owing as much to 19th century pedal harp practice as to the hand position of the 18th century harpers including Arthur O’Neill. And so I wonder if the simple overhand knot might somehow be influenced or derived from the way a gut string is knotted on a pedal harp?

Conclusions

William Savage tells us in his notes that George Jackson, a student of Pat Murney, strung his harp. The physical remains on the harp are consistent with Jackson having designed the stringing regime, and having installed almost half of the surviving strings.

The letter dated June 1908 implies that the harp had been completed and strung not long before, so we might suppose that the stringing was done in the spring of 1908. George Jackson was then apparently aged 74 or 75, and living in Clifton House; he died a year later in July 1909.

Savage’s letter to Armstrong says “The strings also brass, have a beautiful tone, in fact, surprising, and far beyond anything I had anticipated. The tuning has risen the sound box so that now it has the same rise as the original”. To me this implies that George Jackson not only fitted the strings to the harp, but also brought the instrument up to pitch. Savage’s notes on “Irish Harpers particularly from Belfast” says that “George was a fair player of the Harp”. Did Jackson play a bit on Savage’s Brian Boru harp replica?

Strings are very ephemeral. It is very very difficult to be able to say when a given string was put onto a harp. I have been wondering for a while if any of the old harps have remaining strings that were put on by a harper in the old tradition. I think it is very hard to tell, and it is likely that most of the strings we see on the old harps today (if not all of them) were put on by outsiders after the end of the instrument’s working life.

William Savage’s harp is a bit of an outlier, in that it was not made in the old tradition, and it seems that it was not a working instrument. but in some ways this helps us; a display harp is less likely to have strings swapped on and off than a working or abandoned harp. William Savage’s harp has a good provenance from when it was made down to the present day, with only three owners since new. And we are told that it was strung by someone who learned at the very end of the inherited tradition.

Many thanks to National Museums Northern Ireland and to Tríona White Hamilton for answering my queries, for finding William Savage’s harp in the catalogue, for facilitating my access to view and measure the strings, and for allowing me to take and use the photographs here. Thanks also to the Royal Irish Academy Library for allowing me to see and photograph Robert Bruce Armstrong’s papers.

in 2010 I wrote a page about the badge which Savage mentioned in his letter.

Simon,

I have read you post with much interest. What an exhaustive description! I was unaware of the existence of this harp. Sean O’Riada had a genuine soft spot for the old Irish metal strung harp. It was for this reason that he preferred the harpsichord to the piano as it could more faithfully replicate the sound of the earlier corpus of Irish music. My daughter played the ‘neo-Irish’ harp for many years, but when she left school she lost interest and never got back to it. He teacher was an elderly Welshman and he died shortly after, which may help explain her loss of interest. During the 1980’s, I toyed with the idea of making a Brian Boru replica myself, but it never got off the ground. I actually had a set of metal strings that I was going to trial on my daughters harp, but the hustle and bustle of raising a large family put the caip bais on it. I have enjoyed your post immensely.

I found George Jackson’s wedding certificate. (at least I assume it is him). The wedding was on 4th September 1860, and George Jackson is listed as a bachelor, clock maker, living in Belfast. His father is given as Charles Jackson, shoe maker. The bride was Annie Linden, a minor, a spinster, no occupation, living in Belfast. Her father was Mr Linden, I think a cork cutter? (it is hard to read).

George would have been about 27 years old when he was married.

I found their daughter Jane’s birth record. Jane Jackson was born on 3rd February 1866 at 3 Foreman St. Belfast, where the family lived. I haven’t found more about her yet – there is a Jane Jackson who died age 3 in 1869 but no more details are given. Is this her?

I also found Annie’s death certificate. She died of heart disease at the general hospital on 1st February 1872, aged 28 (which makes her 16 when she was married). her occupation is given as “servant”. George was only 38 years old when he was widowed.

I found an advertisement in the Ulster Examiner and Northern Star, Thursday 30th April 1868:

CLOCKS! CLOCKS! CLOCKS!

—-

CAMPBELL & COMPANY

BEG TO INFORM THE

public that they have

engaged

MR. GEORGE JACKSON

(FORMERLY OF MESSRS. NEILL, BROS’., AND LATE OF

MESSRS. J. F. HARBISON & CO.’S),

To Superintend their

CLOCK DEPARTMENT

From his long knowledge experience and

practical knowledge of the trade,

parties requiring

NEW WORK

OR

CLOCKS OF ALL KINDS REPAIRED,

May depend on getting Work

done in a superior manner, while

the Charges will be much lower

than what is usually charged

elsewhere.

Turret and all other kinds of

Clocks made to order.

Public Clocks wound by the

Year

A TRIAL SOLICITED.

—-

N.B.–Watches and Jewellery

Repaired, as usual, by first-class

Workmen on the Premises.

—-

CAMPBELL & COMPANY,

8, 9, & 10, SMITHFIELD.

BELFAST, 1868 183

Just to add that I have done a bit more work on the stringing and setup of these 19th century harps and I no longer believe my earlier statements that they didn’t have the unison sister strings. It is quite possible that George Jackson would have intended this harp to have both the bass gap between bottom E and cronan G, and also the two unison tenor g strings. I have added a comment to my study of the stringing and setup of Patrick Byrne’s harp.

I went to the National Museum of Ireland and looked at Rennie’s harp, which William Savage owned in the early years of the 20th century. I managed to take a good photo of the strange tall braces glued to the inside of the soundboard in the bass, and which obviously gave Savage the inspiration for the design of the inside of his Brian Boru harp.

Inside of harp NMI DF:1980.6 looking towards bass