Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.29 page 185/183/192/f91r is a kind of title page for a 16 page pamphlet which is now bound up in the composite manuscript MS4.29. The pamphlet consists of 16 pages in MS4.29, from page 185/183/192/f91r through to page 200/198/207/f98v, and contains live transcription notations of traditional Irish music, which were written down by Edward Bunting on his collecting trips in the 1790s. This pamphlet seems to have been bound up with all his other loose collecting pamphlets in around 1802-1805, to form the volume which is now QUB SC MS4.29.

You can see my suggested gathering structure of the composite manuscript MS4.29 in my PDF (which also explains the reason why I give four different page numbers to refer to one page in this manuscript). I also mentioned this pamphlet 10 months ago. How far we have come since then!

The first page of this pamphlet

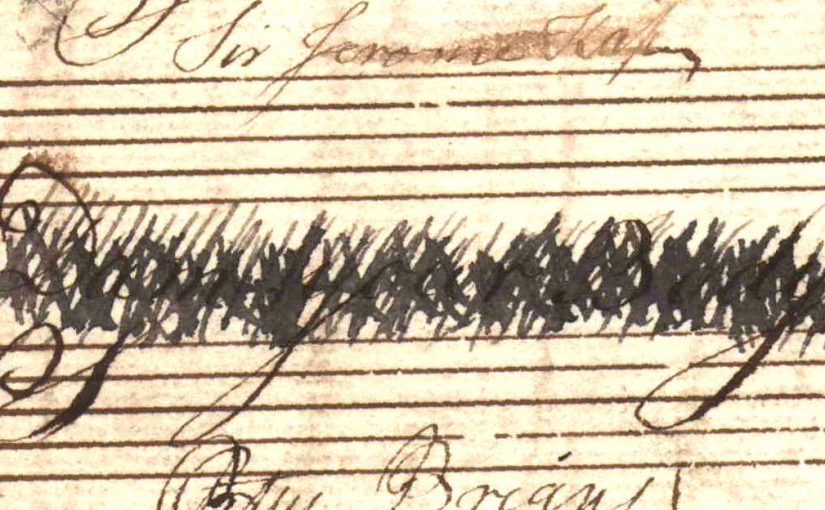

The writing on page 185 is mostly crossed out, and I can’t read most of it. The horizontal writing between the first and second blank music staves reads “Dam[n] your Body” and has been very heavily scribbled out. The sideways writing that has been scribbled out includes the name “Edward Bunting”, and the words “Oh Dear and “My Dear”. There are also some names, “Sir Jerome Ka[??]” and what looks like “Georg”.

Page 185 and also its reverse, p.186, also include the tune of Catty O’Brian. I wrote up a different version of this tune titled Betty O’Brien which is on p108, and on that post I made a machine audio of the p.185-6 notation. I think it looks like it may not be a live transcription, but a neat copy perhaps from a book or other manuscript. I think that the first and last pages of these little independent transcription pamphlets often contain tunes or fragments that were added much later, perhaps even after the pamphlets were bound up together between 1802 and 1805.

If you look at my Old Irish Harp Transcriptions Project Tune List PDF, you can see that the 16 pages of this pamphlet from page 185 to page 200 include a number of interesting tunes which I have not yet dealt with. At the moment I am counting about 23 or 24 different tunes in this pamphlet, almost all of them apparently live transcription notations. Many of them seem to be in non-harp-friendly keys, and 8 of them have attributions to “Byrne”.

So far I have already looked at An Gearran Buidhe & Bean an Leanna on p.187; Planxty Dermot & Cathal Mhac Aodh on p.191, and (in passing) Thugamar féin an samhradh linn on p.200. But I am starting to doubt some of my conclusions in those old write-ups. I am especially interested in the possibility that these tunes might all be notated “one down”, transposed one whole tone lower in the transcription notation, than they would be played in the traditional old Irish harp tunings.

I am planning to work through these manuscript pages one tune at a time, and write each one up here. Then after we have got to page 200, we should have a clearer idea of what is going on with this “Damn your Body” pamphlet.

Many thanks to Queen’s University Belfast Special Collections for the digitised pages from MS4 (the Bunting Collection), and for letting me use them here.

Many thanks to the Arts Council of Northern Ireland for helping to provide the equipment used for these posts, and also for supporting the writing of these blog posts.

I’m sure you’ve thought of this, but I’ve never seen it written anywhere – this is about the keys. We know that in the time of the Carolan a pitch of “B” somewhere could be an “A” in the next town or next house. At least that was true of much of Europe; I don’t know specifically about Ireland.

So if Bunting had “perfect pitch” and that seems a very good skill to have for a job like that, it was likely the pitch of the organ in his town. So a harpers “b” might be notated otherwise to match his own ear. I don’t see any thought that the harpers tuned to any standard pitch either . Do you see any evidence of this either way?

You are correct, we have no direct information about pitch standards of the traditional harpers. I don’t think we should expect to have any real evidence of the harpers’ pitch standard or temperament – the biggest study of this for Classical music is Bruce Haynes, A history of performing pitch: the story of ‘A’ (2002) which mostly relies on wind instruments such as organs, clarinets, etc. whose pitch is fixed at the time of being made.

I discussed this a bit in my article last year in the Galpin Society Journal (p.104) – I suggest that at the time Bunting was collecting in the 1790s, the urban classical pitch standards seem to be about modern pitch or about a quarter-tone lower.

Bunting’s “job” was as a church organist in Belfast – and it does look from his transcription notebooks that he was able to consistently do transcription dots at the actual pitch level for “harp friendly” keys, but also that he sometimes seems to be all over the place. But we also need to bear in mind that some of his notations were from singers, not harpers (and a singer can sing in any key or pitch level they want); and other notations were copied from keyboard books or manuscripts, which could be set in any key.

We need a statistical and aggregate overview to be able to say if there is significance in the groups of tunes that may be at pitch or transposed a note up or down. I’ll work through this pamphlet and we will see if there is any consistency in the pitch levels he has written his transcription dots.

I have often thought the same thing myself Simon. The ability to standardise middle C at 256 Hertz is of relatively recent times. In the final analysis, I’m not sure if it really matters if our scales at various times are up to half a semitone out – especially for someone like me. I am a long way down from those individuals blessed with ‘perfect pitch’. I am in awe of people like you that can even tackle such uncertainties from our earlier corpus of musical heritage. Keep up the great work!

You are right, of course for a solo practicioner, within a semitone is all that is needed.

If you are playing with another musician, you have to be tuned accurately to them, (for example in a class or session or ensemble situation).

I’m asking a different kind of question, which is more like, is there an offset between the 1790s informant and Bunting’s ear? If a late 18th century harper sounded na comhluighe (which we would conventionally give the letter name “G” no matter its actual sounding pitch level), did Bunting put a dot on the staff in the position for G, or for A, or for F, or what? And the reverse, if we see a dot in the G position, can we work out whether that might represent na comhluighe, or a note higher, or a note lower? This is important to be able to understand the mode and structure of a tune from the live transcription notations