Daniel (or Donald) Black was a traditional Irish harper in the 18th century. He was alive in 1792 and so we have to say something about him as part of my Long 19th Century project, to investigate the traditional Irish harpers who were active from 1792 onwards.

As part of my Long 19th Century project I am not paying much attention to what the traditional harpers were doing before 1792, except in how it frames or helps us understand what they were doing from 1792 onwards. For Daniel Black, the period before 1792 is the vast bulk of his life, yet we seem to have virtually no information about this. We can calculate where and when he was born, but we know nothing about how he learned the harp or what his professional career was like.

So in this post I am going to talk about what he was doing from 1792 onwards.

In Belfast, 1792

We first meet Daniel Black in Belfast in July 1792, at the famous gathering of the traditional Irish harpers. Black is listed in the newspaper report which tells us the order the harpers played in, and the tunes they played:

DANIEL BLACK, (blind), from the county of Derry, aged 75.

Belfast News Letter, Fri 13 Jul 1792 p3

Played – The receipt for drinking Whiskey – Carolan.

Sir Alick a Burke – The same.

Thomas a Burke – The same.

This brief clipping gives us some key information: that Black was blind; that he was from County Derry, and that he was aged 75 in July 1792. From that we can calculate that he was apparently born in 1716-17. However we cannot necessarily trust the ages given in this news clipping.

The harper and tradition-bearer William Carr, who was at the Belfast meeting in 1792, later remembered Daniel Black. On Wed 18 Feb 1807, Carr told the English traveller John Lee about the harpers he remembered attending the Belfast meeting. Carr did remember Black being there, but he did not remember much. The only information that Lee wrote down from Carr’s reminiscencing is four words: “Daniel Black (dead since)”. (ed. Angela Byrne, A Scientific, antiquarian and picturesque tour – John (Fiott) Lee in Ireland, England and Wales, 1806-7 Routlege 2018 p.303)

At Glen Oak, 1796

Edward Bunting tells us that he met Daniel Black at Mr Heyland’s House, near Crumlin, in 1796, and that he wrote down tunes from Black’s playing.

DANIEL BLACK, a harper from Derry who attended the Belfast meeting, was born about the same time with Mungan. His chief resort, when in Antrim, was Mr. Heyland’s seat at Glendaragh, near Antrim, where the Editor saw him shortly before his death, in 1796. He sung to the harp very sweetly.

Edward Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland, Dublin, 1840, intro p.78

We can read between the lines here. Bunting says “His chief resort, when in Antrim, was Mr. Heyland’s seat at Glendaragh…” which implies that Black was travelling; that he was only in County Antrim part of the time; but that when he was in Antrim he would stay at Mr Heyland’s House. We can only guess where else Black travelled, which other patrons he visited, and how he organised his time.

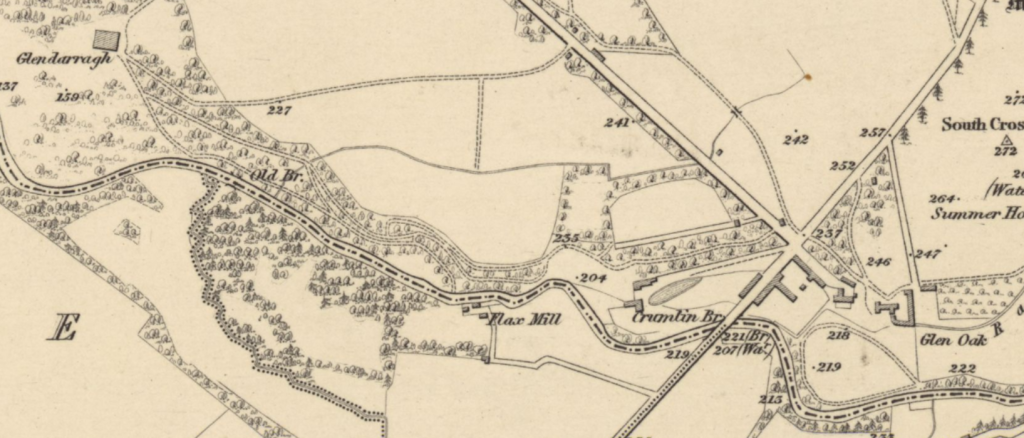

We have a problem here, in that Glendarragh House was built in 1805, and so I think it is not the house that Black went to and where Bunting met him. You can see Glendarragh house on the satellite photographs; it was described in 1999. I understand that it was built around 1805 by Lt. Col. Langford Heyland (1772 – 1829). I presume that by 1840 Bunting had forgotten the specifics of exactly where he had been, and he may have latched on to Glendarragh as “Mr. Heyland’s seat” (perhaps even looking it up in an early 19th century directory), and not realised his error of dating or chronology.

Lt. Col. Langford Heyland’s father, Rowley Heyland JP (1720s – 1800), must be the man who was Black’s patron and whose house Black was staying at when Bunting met him in 1796. In 1765, Rowley Heyland had built “the first industrial mill in the north of Ireland” in Crumlin Glen beside the Camlin River, and beside the mill was Glen Oak house which has been described as the “mill owner’s house” and dated to “before 1780” (UAHS second list of West Antrim, 1970, p9). A more detailed description of Glen Oak House from 1999 says it was there by 1782, the residence of Rowley Heyland. There is also a photo of Glen Oak (and also of Glendarragh) in in Brett’s Buildings of County Antrim; you can see Glen Oak on Google Street View.

By 1817 the Heyland family had sold Glen Oak house (and the mills I think) to McAuley, who took over the mill business. I imagine Rowley Heyland’s son, Lt. Col. Langford Heyland, deciding to sell up and retire on the profits of the mill business; building Glendarragh in 1805 as a country house with a big parkland and wooded estate. If this story is true, we can understand how in 1840, Bunting could have written that Black was at “Mr. Heyland’s seat” and then added without thinking it through, “at Glendaragh”. At this stage, I think we can be cautiously certain that Black must have stayed with Rowley Heyland at Glen Oak house, just to the east of the Crumlin Bridge.

Crumlin Glen is open the public as a woodland walk with a car park next to the Crumlin bridge. My header photo shows the Camlin River in Crumlin Glen.

Death and legacy

Bunting tells us he “saw him shortly before his death, in 1796”. This is usually understood to mean that Black died in 1796, and that Bunting saw him shortly before; but it could also mean that Bunting saw him in 1796, and that Black died shortly after. It seems likely that Black died in 1796, but it is possible his death was in 1797. It depends on how long “shortly” is.

I don’t have any death record or notice for Daniel Black. Apart from William Carr’s very terse comment mentioned above, the only memories or references to Black after his death that I have found are the information collected by or for Edward Bunting. We will discuss all that stuff next.

Information on the method of playing

Edward Bunting tells us that Daniel Black was one of the sources for his list of the Irish terminology and the traditional playing techniques. Bunting explains:

The following collection of these native terms of art was procured from the most distinguished of the harpers who met at Belfast, in 1792. Their vast importance in establishing the antiquity of the country’s music was first pointed out to the Editor by Doctor James M’Donnell, of that town, who zealously assisted in forming the collection. The harpers whose authority was chiefly relied on were Hempson, O’Neill, Higgins, Fanning, and Black… Although educated by different masters, (through the medium of the Irish language alone,) and in different parts of the country, they exhibited a perfect agreement in all their statements, referring to the old traditions of the art as their only authority, and professing themselves quite at a loss to explain their method of playing by any other terms.

Edward Bunting, The Ancient Music of Ireland, Dublin 1840, intro p19-20

This is a little difficult to parse so we can try to paraphrase Bunting’s rather complex and ambiguous language. Bunting tells us that Dr. James McDonnell told him the importance of collecting technical vocabulary, and that Dr McDonnell helped in collecting the information. Bunting tells us that he got the information “chiefly” from five traditional harpers: Dennis Hampson, Arthur O’Neil, Hugh Higgins, Charles Fanning, and Daniel Black. Bunting describes these five men as “the most distinguished of the harpers who met at Belfast, in 1792”. I think he means that they met in Belfast in 1792, and not hat he collected the information in 1792 – so we don’t know when the information was collected. We also don’t know what Dr McDonnell’s role in the process was; did he merely encourage Bunting, and organise visits to the harpers; or did Dr McDonnell actively transcribe information from the tradition-bearers and send it on to Bunting to collate and publish?

Bunting also tells us that the five harpers were educated “through the medium of the Irish language alone”, so we can say with some confidence that Black was an Irish speaker and had learned to play the traditional wire-strung Irish harp in the inherited tradition through the medium of Irish.

Tune lists

We have two tune lists for Daniel Black. We also have some attribution references scattered through Edward Bunting’s classical piano arrangements of Irish tunes. We can consider each of these sources in more detail.

Newspaper tune list

We have already looked at this news clipping for evidence about Black’s life and movements. Now we can look at it again to talk about the tunes listed.

DANIEL BLACK, (blind), from the county of Derry, aged 75.

Belfast News Letter, Fri 13 Jul 1792 p3

Played – The receipt for drinking Whiskey – Carolan.

Sir Alick a Burke – The same.

Thomas a Burke – The same.

Carolan’s Reciept for Drinking Whiskey is also known as Dr. John Stafford. I’m not finding a traditional performance of Carolan’s Receipt to show you – it looks like it disappeared from the tradition, to be reintroduced via classical-style harp re-discovery. Edward Bunting published this tune in 1840 p.54; he said he got it form the harper Black but I haven’t found a live transcription from a traditional harper. There is another attreibution to Black in Bunting’s late 1830s piano manuscript, QUB SC MS4.13. However these atrribution tags were written into the piano arrangements over 40 years after the collection sessions. The tune was well known in late 18th and early 19th century keyboard arrangements and Bunting does not seem to have kept accurate records of his sources, and so I strongly suspect that rather than being an accurate indication of Black having been Bunting’s traditional source for the tune, these tags are merely lifted from the newspaper clipping. But we can be fairly sure that Black did play a version of the tune in Belfast in July 1792.

We have two different tunes for Sir Ulick Burke composed by Carolan. Perhaps more likely is no.8 in Donal O’Sullivan’s Carolan (1958). If we look at my Carolan Tune Collation spreadsheet we can see that it was first printed during Carolan’s lifetime, in 1724 by John and William Neale. Carolan also composed a lament or elegy for Sir Ulick Burke, which is no.206 in Donal O’Sullivan’s Carolan. It is possible that this marbhna was what Black was playing. But we can be fairly sure that Daniel Black played a version of one of these two tunes in Belfast in 1792.

We have two tunes attributed to Carolan titled Thomas Burke. One is DOSC 13, which was first printed during Carolan’s lifetime by Neal. We have a different tune titled the Honourable Thomas Bourk (DOSC 11) which was printed in Lee in the late 18th century. Presumably Daniel Black was playing one of these two tunes but I don’t know how to tell which. There is a third tune by Carolan titled Plangsy Bourk (DOSC 14) but I think that is less likely.

I think all three of these tunes which Black played in Belfast in 1792 share features; they are all by Carolan, and they are all apparently Carolan’s more upbeat style of composition (often referred to as “planxty” even if not titled that). And it seems to me that all three fell out of the tradition in the 19th century, to be re-introduced from Donal O’Sullivan’s book in the second half of the 20th century.

Bunting manuscript tune list

In Edward Bunting’s little collecting pamphlets from the 1790s, there is a tune list which shows eight tunes collected from Daniel Black. This list is from a completely different context. I think that the Belfast newspaper tune list shows Black choosing “crowd-pleasers”, trying to make a good impression in the competition. But this manuscript tune list looks more like Edward Bunting looking for the most ancient and obscure stuff to pad out his collection of tunes. These titles in the manuscript tune list are more like sean-nos song airs.

{Peggen a Leaven Daniel Black

Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.29 p.178/176/185/f87v

+{Brough ne Shannon ditto——–

{Garran Buoy yellow horse Ditto —-

{Collin Fin ——— Ditto ——–

{Black bird & thrush Ditto ——–

{Little hour before Day Ditto ——

{Castle Moon Ditto ——-

{Huar ma fian Ditto ———-

Now of course we can be dubious about Edward Bunting’s working methods. At first sight we could take this manuscript tune list as being Bunting’s record of what tunes he had notated live from Daniel Black’s playing or singing. But it is also possible that this is not a list of live transcription dots, but just a list of tunes that Bunting had heard Black play. And it is also possible that this list does not reflect anything real about Black, but that it could be Bunting’s initial attempts to create spurious provenances for his work by organising traditional tune titles under the names of harpers. We can try to work out which of these possibilities seems more likely by looking in turn at each title.

I have written up all of these previously as part of my Transcriptions Project. Irritatingly, all the links to the online facimiles of QUB SC MS4.29 have broken since I wrote up the individual tunes. I will try to insert current links to the facsimile pages into this post. You can use my ms4.29 index to work out the different page number systems

The first title, Peigí Ní Shléibhín, is perhaps the most problematical. The tune and perhaps the song of Bonny Portmore may have been collected by Edward Bunting from the playing and perhaps also the singing of Black at Gendarragh in 1796. However Bunting completely mixed up the tune and title of Bonny Portmore with the superficially similar (though structurally different) song air Peggy Ni Leaven which I don’t think he collected from Black. I discuss my thoughts on these attributions on my write ups of the two different tunes, Bonny Portmore (ms4.29 p218/216/225/f107v) and Peggy Ni Leaven (ms4.29 p106/102/111/f50v).

Ar Bhruach na Sionainne is a song air which Edward Bunting notated live from a harper informant in 1792 or perhaps more likely in 1796 (QUB SC MS4.29 p104/100/109/f49v). I wrote a post about this live transcription notation and I suggested there that this live transcription dots may have been written from Black’s playing and/or singing at Glen Oak in the summer of 1796.

Edward Bunting made more than one live notation of the tune of an gearrán buidhe. One of these live notations, on QUB SC MS4.29 p96/92/101/f45v, may have been made live from Daniel Black’s playing. I wrote up a post on the different live transcription versions of this tune.

The live trancription notation of the tune of Cúileann fín also appears in the same pamphlet (p.95 – 96) with the other possible transcriptions from Black, and on the same page as an gearrán buidhe (above) and An londubh agus an chéirseach (below). However in my post on this tune of Cúileann fín, I suggest that it seems likely not transcribed live from Black. I suppose it is possible that it was part of a first layer of transcribing in the manuscript, and the Black tunes may have been inserted later around it. Which then begs the question of whether Bunting compiled our p178 tune list from tunes that Black actually played, or by going through a collecting pamphlet that contained some genuine Black live transcriptions and adding all the titles from that pamphlet, forgetting that some predated the Black collecting session. I do not know the answer and it is extremely frustrating and makes this whole exercise seem pointless.

An londubh agus an chéirseach (The Blackbird and the Thrush) was apparently transcribed live on the same page as Cúileann fín (p95). I wrote up this live transcription and I suggest there that it seems possible that this rough notation and others on adjacent pages may have been transcribed live from Black’s playing – Of the 8 tunes in this list on p.178, there are live transcriptions of five of them on pages 93 through to 96 of MS4.29

Uair bheag roimh an lá (little hour before day) is another tune that was transcribed live by Edward Bunting onto QUB SC MS4.29 p94/90/99/f44v, the page before the group of tunes discussed above. However it appears to be a different pamphlet and not contiguous with pages 95-102. I wrote up this page of the manuscript and discussed the problems with trying to claim that this tune and its neighbours in the manuscript may represent live transcriptions from Black.

Caiseal Mumhan (written phonetically as Castle Moon) is another title for Clár bog déil (soft deal boards) which we find in a live transcription from the 1790s in QUB SC MS4.29 p93/89/98/f44r. (the previous page to the tunes discussed above). I wrote up this page of the manuscript and wondered there if it might or might not derive from Black’s performance. I also discussed strange symbols that appear on some of the tunes.

Edward Bunting made live transcription notations of two versions of the tune of Thugamar féin an samhradh linn from two different traditional informants. I wrote up the live transcription notations, and suggested there that the notation on MS4.29 p200/198/207/f98v may be a live transcription of Daniel Black’s playing.

The fact that this tune list is in Bunting’s bound up collecting pamphlets makes it very tempting to try and match the tune titles in the list with the unattributed live transcription dots. But even if we can be dubious about the provenance of almost all the dots notations, we can still be fairly confident that this tune list tells us some of Black’s repertory.

Other tunes attributed to Daniel Black

In his later piano books, Edward Bunting tags a number of developed classical piano arrangements with Daniel Black’s name. On my Transcription Project Tune List I count 12 different tunes that are written with “Black” attributions on the later classical piano arrangements. Now I generally don’t trust these attribution tags; they were usually written down decades after Bunting’s collecting activities, and I really do wonder if he just made up attributions or at best vaguely mis-remembered who played what tunes. And in any case he is writing the attributions down beside classical piano versions of the tunes, which have been thoroughly de-traditionalised and harmonised with the melodies often changed and with the titles either changed or sometimes hopelessly muddled up. But we should check each tune and its source and attribution.

As usual with tune lists, we can never be quite sure what versions of each tune the titles given actually refer to, but we can be fairly certain that some tune referred to by each title was actually played or sung by Daniel Black.

Róis bheag dubh (Rosey Black) is a version of Róisín Dubh which seems to have been collected by Edward Bunting from the playing and singing of Daniel Black. Bunting described the performance:

… It was sung for the Editor in 1792, by Daniel Black, the harper, who played chords in the Arpeggio style with excellent effect…

1840 intro p.97

Unfortunately for us, Bunting collected three different versions of the tune of Róisín Dubh, and he muddles up the different attributions. I discuss these versions and the attributions in my write up of this tune and its sources. I think that it seems likely that the live field notation on MS4.29 p62/58/67/f28v may derive from Black’s playing and singing. (note the facing page has a version of Ar Bhruach na Sionainne, a title in the Black tune list discussed above). Edward Bunting completely muddied the waters by publishing in 1840 a synthetic piano arrangement of Róisín Dubh; for the tune, Bunting discarded the live transcription that he may have got from Black, and instead, he used a version of the tune which he had collected from a singer in Castlebar in 1802 as the basis for his piano arrangement on page 16-17 of his 1840 book; and he added to this vocal melody a classical piano arrangement of descending arpeggiated chords obviously inspired by an impressionistic memory of his description of Black’s playing. Bunting’s text on p97 of the introduction seems to continue by describing not Black’s harp playing, but Bunting’s own piano arrangement: “The key-note at the end of the strain, accompanied by the fifth and eighth, without the third, has a wailing, melancholy expression, which imparts a very peculiar effect to the melody.” I think this sentence tells us nothing about what Black actually played.

I think we have to be very careful with this kind of passage that Bunting writes. The first sentence is clearly an impressionistic description (albeit over forty years later) of Black singing the song of Róisín Dubh and playing, not the same melody that he sings, but some kind of chordal or drone-based or resonant accompaniment on the harp. However the second sentence I think we should understand not as a description of Black’s harp accompaniment, but as Bunting’s description of his own piano arrangement on page 16-17 of his 1840 book. That piano arrangement does indeed have an open G-D-G piano chord “at the end of the strain” but the tune there is a different version, and the bass is Bunting’s own piano arrangement.

Brighit Óg (Young Bridget Cruise) is a song by Carolan. Edward Bunting apparently collected this tune from a harper informant in the 1790s; his live transcription is on the next opening after Roisín Dubh, in QUB SC MS4.29 p64/60/69/f29v. The facing page contains a neat copy of the tune, and then in 1797 Bunting made a piano arrangement based on this live transcription, which includes the attribution to Black and a fragment of the Irish song lyrics. It seems likely that Black sang this Carolan song to Bunting some time in the 1790s. I wrote up this tune and its sources here.

Sín Síos agus Suas liom is attributed to “D. Black Harper 1796” in the 1840 index p.viii, and the Black attribution is also given in the late 1830s piano manuscripts, MS4.13 and MS4.27. However, we have two different live transcription notations, and it is not entirely clear if one or the other of them may have been collected live from Black. In my write up of this tune and its sources I suggest that the live transcription dots on QUB SC MS4.29 p104/100/109/f49v (the same page as Ar Bhruach na Sionainne discussed above) might possibly have been written down live from the playing of Daniel Black at Glen Oak in 1796, but this is just guesswork.

Síle Bheag Ní Connellan (Litte Celia Connallon) is attributed to Black in the 1797-8 unpublished Ancient and Modern piano manuscript. This is the more vocal setting of the two different versions that Bunting presents. I don’t think we have a field transcription dots of this version of this tune, only the 1797-8 piano arrangement. The piano arrangement is in QUB SC ms33.3 p9; the attribution at the bottom says “From Donald Black’s singing & also from Charles Byrne”, as if both men had sung the song to Bunting and he had made a synthetic combination of their two versions on which to base his classical piano arrangement. I tend to be more accepting of these early attributions so I think we might believe that Daniel Black did sing this song to Bunting in the 1790s.

Dubious attributions

Edward Bunting added source attributions to almost all of the tunes that appear in his 1840 printed book. The same or different attributions can be found in the preparatory manuscript piano books from the late 1830s, QUB SC MS4.13 and MS4.27. And then I presume after the 1840 book was published, Bunting went through his own personal copies of the old 1797 and 1809 printed books, and hand-wrote new attributions against almost all of the tunes in them.

All of these attributions were done in the late 1830s and early 1840s, forty years or more after the collecting trips. So in the absence of any corroborating evidence I tend to ignore these attribution tags as being spurious and invented. But we can still go through the tunes that do have these late attribution tags to see if we can say anything useful about them to connect them to Daniel Black.

Bacach buidhe na léimne (the Lame yellow beggar) is attributed to “D. Black, harper, 1792” in the printed 1840 index p.xi. However, in the late 1830s the preparatory piano manuscripts gave conflicting attributions, to Black in MS4.13 and to James Duncan in ms4.27. I suspect these attributions are being made up. In a much earlier piano arrangement made in 1798 (MS4.33.3 p8) Bunting attributes this tune to Charles Byrne which is perhaps more likely, so perhaps we can cross this one off our Daniel Black list. I wrote up this tune and its sources here.

An bhfaca tú mo valentine was attributed to Black in an annotation to the printed score which was written into the book in the early 1840s. However I don’t know whether or not we can trust this attribution. I have already written up this tune and discussed these attribution problems here.

Carraige an Aoibhnis, also called Clanuff’s Delight or the Rocks of Pleasure, was attributed to Black in the early 1840s, when Bunting added handwritten annotations into his first printed book. Donal O’Sullivan made an error transferring these attributions into his edition of the Bunting tunes in the 1920s but I don’t think it really matters because I don’t believe these late attributions, written in almost 50 years after the field collecting.

Abigail Judge similarly has “Black” as its attribution in the annotated 1797 print; there is a different attribution to “O’Neil” in the annotated 1809 print. Both these attributions were written into the printed books in the early 1840s and I think we can ignore them both.

Coillte Glasa an Truicha also has “Black” as its attribution in the annotated 1809 print, written into the book in the early 1840s. I don’t think we need to pay any attention to this.

In the end none of this really matters, because I am sure that most of the professional harpers knew a wide range of the repertory and I am sure that Black, like many of his contemporaries, would play most if not all of these tunes mentioned above.

Daniel Black’s harp

Daniel Black’s harp was obviously not made during our Long 19th Century study period (1792-1909) but it was being played at the very beginning of the period, and so we can briefly discuss what little we know about it here.

We do not have Daniel Black’s harp, but we do have a description of it, which was written down by Dr James McDonnell in about 1839. McDonnell explains his project to document the different harps played by the late 18th century tradition-bearers:

…with a view to discern the theory of the curve

Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.35.16b

in the pinboard I had all the Harps measured

carefully& prepared forpreparatory to engraving

them upon a scale, but these notes are lost by

Mr John Mulholland, who took them to London

I had no duplicate –

In the same letter, McDonnell briefly describes Black’s harp. It is not clear to me if this is from memory or if he had some notes he was copying from.

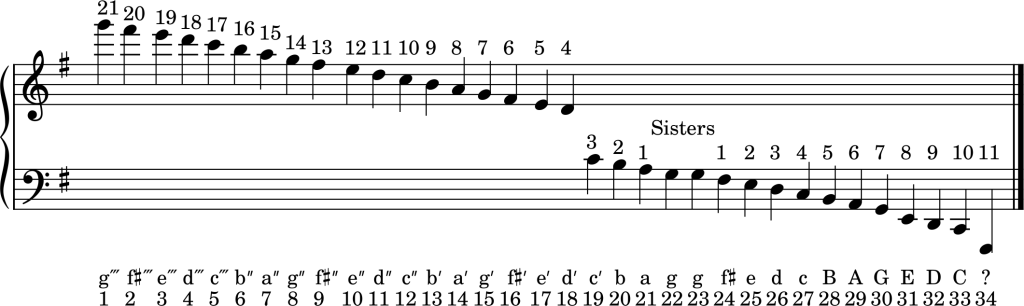

Black’s had 11 below, & 21 above Sisters – it

Queen’s University Belfast, Special Collections, MS4.35.16a

had 3 circular, divided, openings in the Belly

resemblingthose ofa Guitar – the Pin-board

was warp’d, which did not impair its tone –

We can make a diagram to show the likely range and tuning of Black’s harp. The “Sisters” (na comhluighe) would be the two strings tuned to tenor G.

I suppose the only real problem we have here is that we don’t know the disposition of the bass strings on Black’s harp. We know from the traditional tuning information that we need the gap at bass E/F (next below cronan G, string 31 from the top on Black’s harp), but I am less certain how the strings below bottom D might be tuned. I think these are the strings labelled “organ” in Edward Bunting’s live transcription dots of tuning cycles from other harpers, and so I think these organ strings are tuned to be sympathetic strings to the ones actually played. On my chart I have made the very lowest string un-defined in pitch. It could be tuned to G or A or I suppose even B. I think this string would never be played and so I imagine that Black may have re-tuned it to give the best resonance and minimum sympathetic dissonance for the tuning or mode he was playing in.

The description of Black’s harp having a warped “pin-board” is interesting – I think this is McDonnell’s word for the neck of the harp. The neck can twist under string tension and as long as the strings don’t foul the woodwork this should not be a problem for the proper functioning of the instrument.

The description of the “3 circular, divided, openings in the Belly

resembling those of a Guitar” is also interesting. I am not sure if these might be small soundholes with foliate petals in them, like on the downhill harp (shown right), which might imply that Black’s harp had three of these on each side of the soundboard; or whether McDonnell is trying to describe a more substantial parchment rose.